Rather than encourage peace or progress, US Secretary of War, Pete Hegseth, recently advised his generals that the Pentagon will be guided by the 4th century Roman dictum, "Sis vis pacem, para bellum"—"If you want peace, prepare for war." Despite mutual vulnerability in an interconnected world, Hegseth stressed that“the only mission of the newly restored Department of War is this: warfighting… We have to be prepared for war, not for defense. We're training warriors, not defenders. We fight wars to win, not to defend.”

Military spending is skyrocketing—tripling for some NATO allies—like Canada, Poland, Latvia, and Lithuania.

So, what might be done? Is there a way to encourage cooperative, win-win approaches for people and the planet? Possibly.

The US Department of War already has a trillion-dollar budget and it’s projected to be 50% larger—$1.5 trillion—by 2027. Such a surge is only required when a government plans to fight multiple wars abroad and stifle dissent at home. Stephen Miller, (President Donald Trump’s deputy chief of staff), already claims that “we are back to a world that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power.”

Overall, the cost of preparing for more war is almost $3 trillion annually. Worse, if current trends persist, the United Nations warns that “global military spending could reach $4.7 to $6.6 trillion by 2035.”

Yet even that huge cost is dwarfed by the damage caused, with the Global Peace Index reporting, “the economic impact of violence on the global economy in 2024 was $19.97 trillion in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms.” As they note: “This figure is equivalent to 11.6% of the world’s economic activity (gross world product), or $2,446 per person. Military and internal security expenditure accounts for over 74% of the figure, with the impact of military spending alone accounting for $9 trillion in PPP terms the past year.”

Of course, most governments understand that no amount of military spending can guarantee a reliable defense or provide security in the nuclear era. Wars have seldom been winnable over the past 80 years, even for the most powerful. President Trump was correct to note the US has not won a major war since 1947. But that stops neither the current wars nor the extravagant investment to get ready for more.

Clearly, higher military spending leaves less for social security, climate action, healthcare, education, and poverty reduction. Precarious conditions spread, giving rise to extremes that generate further insecurity, with new risks of race, class, and civil conflict. Trust in government erodes when funds are available for weapons but not for human needs. Militarism follows, deepening a culture of violence, poverty, and extremes.

As President and General Dwight D. Eisenhower said: "Every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired signifies... a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed... Under the clouds of war, it is humanity hanging on a cross of iron."

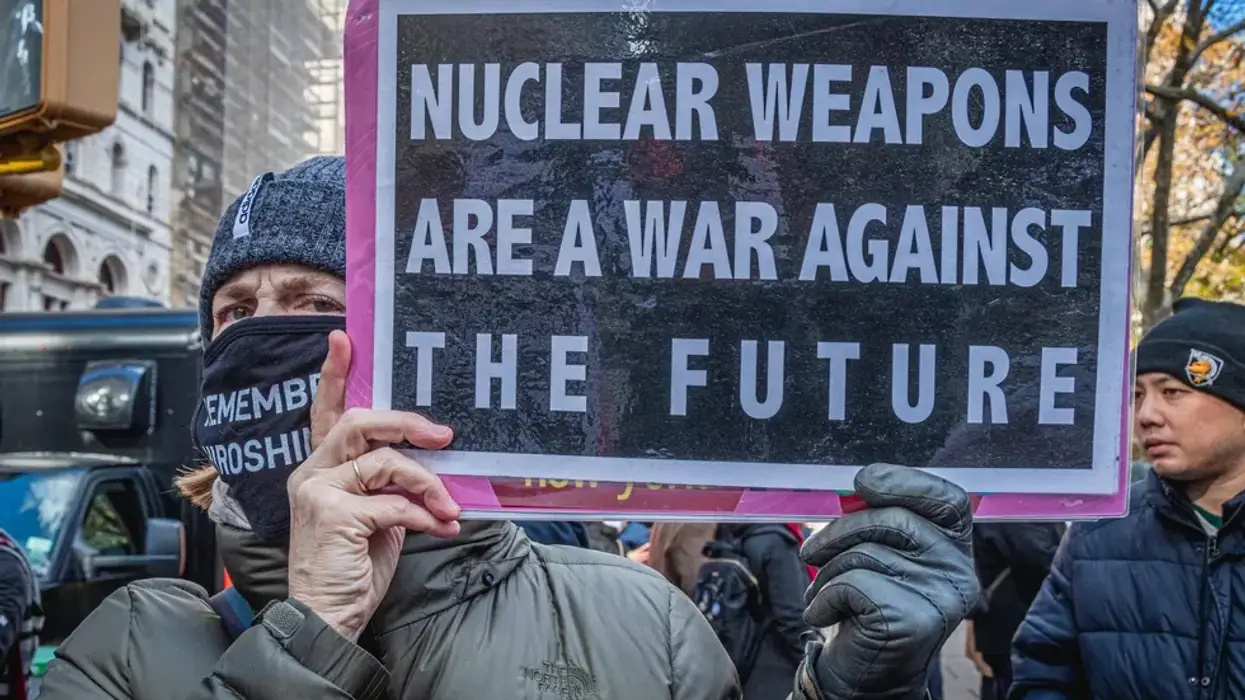

With ever-higher costs, there are ever-higher risks. All the great powers are modernizing and expanding their nuclear arsenals. They still rely on nuclear deterrence, with a threat of total destruction held in check by rational leaders who are supposed to maintain a system of mutually-assured destruction (MAD) in a "balance of terror." Oh, oh! Even a limited use of nuclear weapons is understood to risk "nuclear winter," with starvation for those who remain. Just last month, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists reset the hands of their Doomsday Clock at 85 seconds to midnight, the closest the world has ever been to catastrophe.

"Caveat emptor"—countries, like people, eventually get what they plan, invest in, and prepare for. Many are already suffering from the violence and militarism they fund, support, and share with others (e.g. foreigners that someone, somewhere labelled as progressives, terrorists, protesters, or activists).

Among the recent targets were Yemen, Nigeria, Syria, Iran, Venezuela, Somalia, Minnesota, Los Angeles, and Portland. Does anyone really think this violence is for peace and security?

Who knows who is next? Will it be Cuba, Columbia, Canada, China, Iceland, Mexico, New York, Maine, or Iran again?

People heard of the deeper, "complex" problem when President Dwight Eisenhower warned:

In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.

With globalization and generous funding, this complex expanded worldwide into finance, banking, and insurance sectors; big oil and gas; telecommunications; logistics; media; surveillance; big data; robotics; and AI.

Eisenhower’s warning wasn’t enough to stem the appeal of profits, power, and control. The unwarranted influence is now everywhere, diminishing political autonomy to the point where government leaders believe they can’t say, “No.” And, this complex depends on violent conflict to "keep the old game alive."

In short, endless war continues in a dysfunctional, war-prone system. And, this system is the primary impediment to progress on a shared climate emergency and sustainable development.

"Endless war" is the risk in following the dubious Roman claim from the 4th century: "If you want peace, prepare for war." Notably, the Roman Empire didn’t survive with its massive military spending and constant civil wars. Instead, let’s remember, "Peace is possible, if we prepare for it."

For now, it is crucial to redirect the current trajectory away from more war and a climate crisis—a lose-lose outcome for all.

So, what might be done? Is there a way to encourage cooperative, win-win approaches for people and the planet? Possibly.

UN-Prepared

Over 80 years ago—in the aftermath of two World Wars—the universal challenge was how to confine the institution of war, preferably before it kills more, possibly everyone.

The United Nations was founded in response, primarily as a state-centric, international peace system. "Saving succeeding generations from the scourge of war" is at the forefront of the UN Charter. To its credit, the UN works daily on all the shared global challenges—sustainable development, human rights, climate change, international law, encouraging multilateral cooperation for peace, nuclear disarmament, culture and education, food and water, even more.

Yet the UN remains a work in progress—underfunded, unprepared, and poorly equipped—constrained by its 193 member states, and hamstrung by the Security Council’s veto power. As it stands, the UN cannot prevent violent conflict, enforce international law, or protect people and the planet effectively. These limits reflect the interests and political priorities of the UN’s member states. Global military spending ($3 trillion) is approximately 780 times higher than the UN’s regular budget ($3.45 billion), which is considerably less than the budget of the New York City Police Department.

Yet these priorities and limits are not fixed in stone. The UN still has the advantage of an exceptional charter, universal membership, 80 years of experience, with established programs, operations, and offices worldwide. Notably, people have not experienced another world war in 80 years. It is also widely acknowledged that UN peace operations—in deadly, remote conflicts—have saved millions of lives and billions of dollars.

In short, the UN foundation is sufficiently solid to expand upon. And, this isn’t a radical or original idea either.

Shortly after President Eisenhower’s warning, President John F. Kennedy’s State Department outlined several of the key steps required in "Freedom From War, The United States Program For General and Complete Disarmament in a Peaceful World." As officials noted:

There is an inseparable relationship between the scaling down of national armaments on the one hand and the building up of international peace-keeping machinery and institutions on the other. Nations are unlikely to shed their means of self-protection in the absence of alternative ways to safeguard their legitimate interests. This can only be achieved through the progressive strengthening of international institutions under the United Nations and by creating a United Nations Peace Force to enforce the peace as the disarmament process proceeds.

The Alternative

A new Guide to a UN-Centred Global Peace System outlines 20 steps to strengthen the UN’s capacity to prevent war, uphold human rights, enforce international law, protect the environment, and promote disarmament. Included is a UN Charter review conference (to agree on an option to the P-5 veto), a financial transaction tax, another decade focused on a global culture of peace, a UN Parliamentary Assembly, defense transformation, development of a UN Emergency Peace Service (a more sophisticated option than a UN Peace Force), economic conversion, and a boost for the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Thankfully, work on most of these steps is already underway, supported by committed individuals and organizations. And, those who struggle to make the UN more effective understand that our scattered, siloed, and specialized approaches seldom combine to make a big difference.

What’s been missing is a compelling vision—"Peace on Earth is possible”—along with a coherent plan outlining a sequence of viable policy options. A shared vision should help to encourage the unity of effort and purpose required to mobilize diverse social movements and governments. And, once these steps for a more effective UN are implemented and combined, the result would be a UN-centered global peace system.

Paradigm shifts happen when prevailing systems are deemed inadequate or failing and when another option is widely viewed as better.

This guide is primarily a call to aim higher, pull together, and prepare now for that moment when new possibilities emerge. Cooperation is crucial to building the bridge between diverse sectors of civil society. With modest coordination and support, an inter-sectoral movement becomes possible.

Of course, this idea will be promptly dismissed as naive, wishful thinking, as "mission-impossible" for now. But as the political pendulum swings toward worse, the corrective swing back is likely to open the space and generate support for substantive shifts, even a safer system.

Just consider what’s distinctly different in 2026? Numerous governments are deeply worried and desperate to both avoid and constrain the new predatory hegemon. They know of safety in numbers and most realize that the one promising alternative is in an established multilateral counterweight, a more effective UN.

Within five years, peace on Earth—"mission impossible"—could become not just desirable, but widely supported, then possible. Millions of lives and trillions of dollars saved.

Paradigm shifts happen when prevailing systems are deemed inadequate or failing and when another option is widely viewed as better.

With the peace system proposed, there would be no further need for offensive weapon systems. National armed forces would shrink. Threats and tensions would fade. And, this new global system might cost $15-20 billion, freeing up trillions to help with climate adaptation and sustainable development. Imagine: We prepare for war no more!