Within hours of the shooting, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth announced that the Trump administration was deploying an additional 500 National Guard troops to DC, adding to the 2,200 that are already present as part of what Trump has claimed is a crackdown on surging crime.

In reality, crime had fallen to record lows in the city for over a year before Trump sent in the troops this past August over the objections of DC officials. This week the president falsely claimed that the city had not had a single homicide since his troop surge began.

In comments to the Guardian, Gary Goodweather, a Democratic candidate in next year's mayoral election and a former US Army captain who served in the National Guard, said Trump's deployment of troops against US citizens made such a backlash inevitable.

"If I’m completely honest, we’ve been expecting this. It hurts me to the core,” he said. “Look around us. These are citizens, they’re residents, they’re human beings. Activating the United States military against people within our own country, within Washington, DC, is the wrong message.”

He added that he feared sending even more troops would just "inflame" tensions further.

David Janovsky, acting director of the Constitution Project at the Project on Government Oversight, described the response as an unnecessary overreach.

"No one should be harmed just for doing their job, and our thoughts are with them and their families," he said of the two guard members. "At the same time, we do not believe that sending even more troops into the city is the solution. By sending more troops in, the administration risks inflaming tensions and undermining civil rights. As more information comes to light about this despicable tragedy, we urge against the administration putting more armed troops on our street corners.”

The new surge of federal troops follows a court ruling issued last week by US District Judge Jia Cobb, who wrote that the Trump administration “exceeded the bounds of their authority” and “acted contrary to law” by deploying the National Guard “for nonmilitary, crime-deterrence missions in the absence of a request from the city’s civil authorities.”

That ruling barred the Trump administration from sending any more troops to DC. However, it is delayed from going into effect until December 11 to give the administration time to appeal.

Thus far, no motive for the attack has been determined. But Trump has already begun to use it to stoke fears about Afghan immigrants.

“We must now reexamine every single alien who has entered our country from Afghanistan under [former President Joe] Biden,” Trump said in an address Wednesday night in which he called the shooting an “act of terror.” The US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) then announced that "effective immediately, processing of all immigration requests relating to Afghan nationals is stopped indefinitely pending further review of security and vetting protocols.”

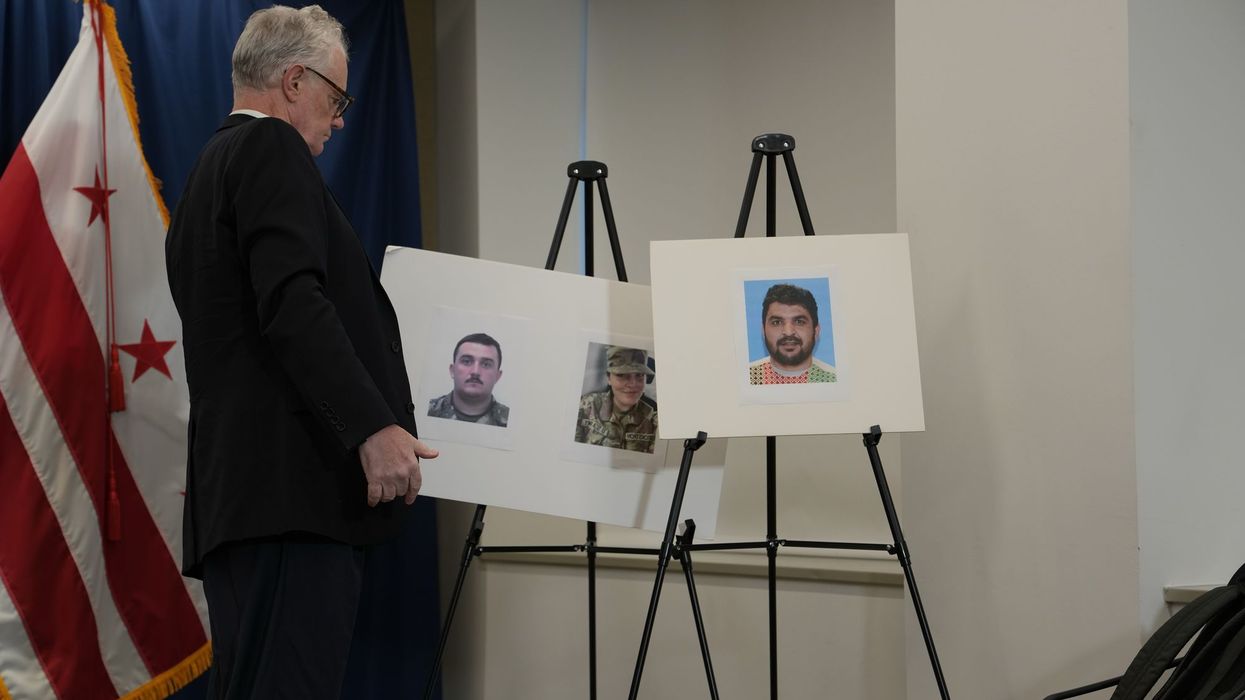

Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem claimed via social media that Lakanwal, the alleged shooter, was "mass paroled into the United States under Operation Allies Welcome," the program to allow Afghans who served alongside the US military to seek refuge in the US following the Taliban's return to power in 2021. According to a June 2025 audit by the Office of the Inspector General, around 90,000 "vulnerable" Afghans were admitted to the US under the program.

While Noem said those admitted under the program were "unvetted," this is untrue. As the audit shows, the program assigned several agencies to screen evacuees, check terror watch lists and criminal history, and attempt identity verification. It stated that in cases where it discovered evacuees on terror watch lists, "in each of these cases, we determined that the FBI notified the appropriate external agencies at the time of watch list identification and followed all required internal processes to mitigate any potential threat."

Trump's pledge to reexamine every Afghan who entered the US under Biden came just days after his administration announced that it was freezing the distribution of green cards for over 235,000 refugees for what it said was “detailed screening and vetting,” even though residents who arrive through the refugee process are already among the most heavily vetted immigrants who enter the United States.

Speaking of the alleged DC shooter, Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a senior fellow at the American Immigration Council, said: "We have no idea what this man’s motive was at this point, and yet the Trump administration is already moving to paint every Afghan as a threat to this country. This comes as the country has dealt with dozens of mass shootings this year alone, carried out by people of varied origins."