We Must End the Global Nuclear Arms Race Before It Ends Us

The question is no longer what is politically possible, but what is virtually guaranteed if we refuse to pursue the “impossible.”

On February 5, with the expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, the only bilateral arms control treaty left between the United States and Russia, we are guaranteed to find ourselves ever closer to the edge of a perilous precipice. The renewed arms race that seems likely to take place could plunge the world, once and for all, into the nuclear abyss. This crisis is neither sudden nor surprising, but the predictable culmination of a truth that has haunted us for nearly 80 years: Humanity has long been living on borrowed time.

In such a context, you might think that our collective survival instinct has proven remarkably poor, which is, at least to a certain extent, understandable. After all, if we had allowed ourselves to feel the full weight of the nuclear threat we’ve faced all these years, we might indeed have collapsed under it. Instead, we continue to drift forward with a sense of muted dread, unwilling (or simply unable) to respond to the nuclear nightmare. In a world already armed with thousands of omnicidal weapons, such fatalism—part suicidal nihilism and part homicidal complacency—becomes a form of violence in its own right.

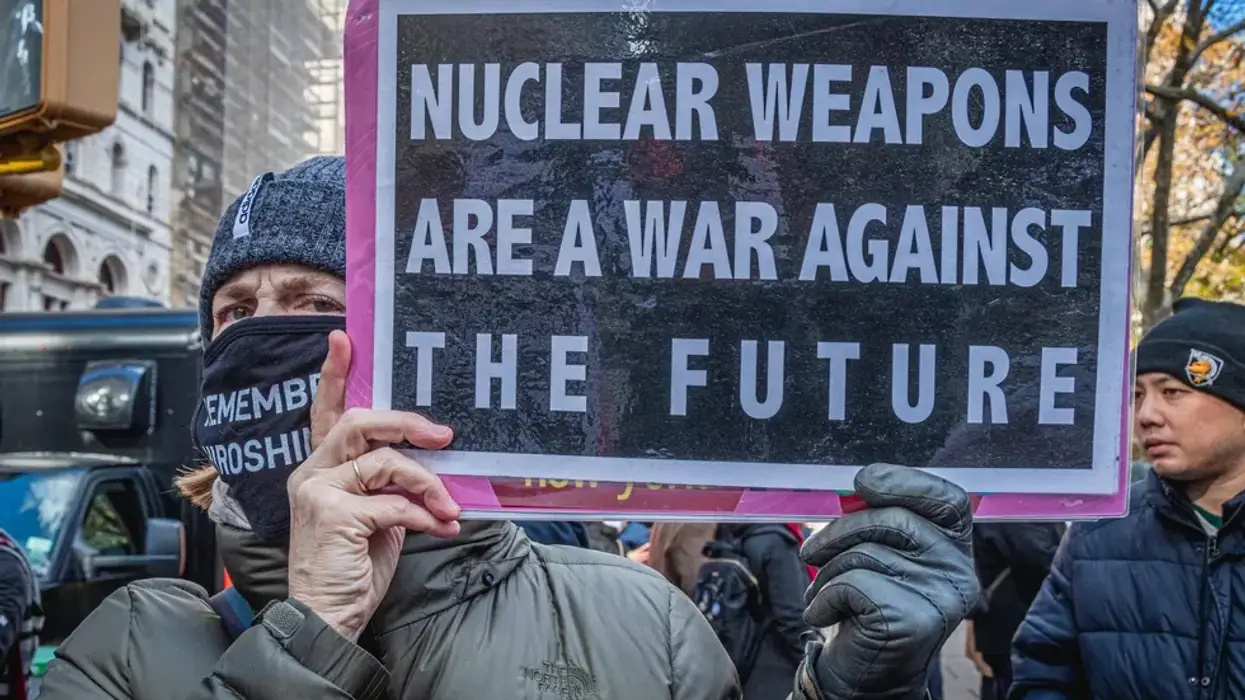

Given such indifference, we risk not only our own lives but also the lives of all those who would come after us. As Jonathan Schell observed decades ago, both genocide and nuclear war are distinct from other forms of mass atrocity in that they serve as “crimes against the future.” And as Robert Jay Lifton once warned, what makes nuclear war so singularly horrifying is that it would constitute “genocide in its terminal form,” a destruction so absolute as to render the Earth unlivable and irrevocably reverse the very process of creation.

Yet for many, the absence of such a nuclear holocaust, 80 years after the US dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is taken as proof that such a catastrophe is, in fact, unthinkable and will never happen. These days, to invoke the specter of annihilation is to be dismissed as alarmist, while to argue for the abolition of such weaponry is considered naïve. As it happens, though, the opposite is true. It’s the height of naïveté to believe that a global system built on the supposed security of nuclear weapons can endure indefinitely.

Nuclear weapons are human creations, and what is made by us can be dismantled by us.

That much should be obvious by now. In truth, we’ve clung to the faith that rational heads will prevail for far too long. Such thinking has sustained a minimalist global nonproliferation regime aimed at preventing the further spread of nuclear weapons to so-called terrorist states like Iraq, Libya, and North Korea (which now indeed has a nuclear arsenal). Yet, today, it should be all too clear that the states with nuclear weapons are, and have long been, the true rogue states.

A nuclear-armed Israel has, after all, been committing genocide in Gaza and has bombed many of its neighbors. Russia continues to devastate Ukraine, which relinquished its nuclear arsenal in 1994, and its leader, Vladimir Putin, has threatened to use nuclear weapons there. And a Washington led by a brazen authoritarian deranged by power, who has declared that he doesn’t “need international law,” has stripped away the fragile façade of a rules-based global order.

Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, and the leaders of the seven other nuclear-armed states possess the unilateral capacity to destroy the world, a power no country should be allowed to wield. Yet even now, there is still time to avert catastrophe. But to chart a reasonable path forward, it’s necessary to look back eight decades and ask why the world failed to ban the bomb at a moment when the dangerous future we now inhabit was already clearly foreseeable.

Every City Is Hiroshima

With Hiroshima and Nagasaki still smoldering ruins, people everywhere confronted a rupture so profound that it seemed to inaugurate a new historical era, one that might well be the last. As news of the atomic bombings spread, a grim consensus took shape that technological “progress” had outpaced political and moral restraint. Journalist Norman Cousins captured the zeitgeist when he wrote that “modern man is obsolete, a self-made anachronism becoming more incongruous by the minute.” Human beings had clearly fashioned themselves into vengeful gods, and the specter of Armageddon was no longer a matter of theology but a creation of modern civilization.

In the United States, of course, a majority of Americans greeted the initial reports of the atomic bombings of those two Japanese cities in a celebratory fashion, convinced that such unprecedented weapons would bring a swift, victorious end to a brutal war. For many, that relief was inseparable from a lingering desire for retribution. In announcing the first atomic attack, President Harry Truman himself declared that the Japanese “have been repaid many fold” for their strike on Pearl Harbor, which inaugurated the official American entry into World War II. Yet triumph quickly gave way to a more somber reckoning.

As the scale of devastation came into fuller view, the psychological fallout radiated far beyond Japan. The New York Herald Tribune captured a growing unease when it editorialized that “one forgets the effect on Japan or on the course of the war as one senses the foundations of one’s own universe trembling a little… it is as if we had put our hands upon the levers of a power too strange, too terrible, too unpredictable in all its possible consequences for any rejoicing over the immediate consequences of its employment.”

Some critics of the bombings would soon begin to frame their concerns in explicitly moral terms, posing the question: Who had we become? Historian Lewis Mumford, for example, argued that the attacks represented the culmination of a society unmoored from any ethical foundations and nothing short of “the visible insanity of a civilization that has ceased to worship life and obey the laws of life.” Religious leaders voiced similar concern. The Christian Century magazine typically condemned the bombings as “a crime against God and humanity which strikes at the very basis of moral existence.”

As the apocalyptic imagination took hold, others turned to a more self-interested but no less urgent question: What will happen to us? Newspapers across the country began running stories on what a Hiroshima-sized bomb would do to their downtowns. Yet Philip Morrison, one of the few scientists to witness both the initial Trinity Test of the atomic bomb and Hiroshima after the bombing, warned that even such terrifying projections underestimated the danger.

Deaths in the hundreds of thousands were, he insisted, far too optimistic. “The bombs will never again, as in Japan, come in ones or twos. They will come in hundreds, even in thousands.” And given the effect of radiation, those who made “remarkable escapes,” the “lucky” ones, would die all the same. Imagining a prospective strike on New York City, he wrote of the survivors who “died in the hospitals of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Rochester, and Saint Louis in the three weeks following the bombing. They died of unstoppable internal hemorrhages… of slow oozing of the blood into the flesh.” Ultimately, he concluded, “If the bomb gets out of hand, if we do not learn to live together… there is only one sure future. The cities of men on Earth will perish.”

One World or None

Morrison wrote that account as part of a broader effort, led by former Manhattan Project scientists who had helped create the bomb, to alert the public to the newfound danger they themselves had helped unleash. That campaign culminated in the January 1946 book One World or None (and a short film). The scientists had largely come to believe that, if the public had their consciousness raised about the implications of the bomb, a task for which they felt uniquely responsible and equipped, then public opinion might shift in ways that could make policies capable of averting catastrophe politically possible.

Scientists like Niels Bohr began calling on their colleagues to face “the great task lying ahead,” while urging them to be “prepared to assist in any way… in bringing about an outcome of the present crisis of humanity worthy of the ideals for which science through the ages has stood.” Accepting such newfound social responsibility felt unavoidable, even if so many of those scientists wished to simply return to their prewar pursuits in the insulated university laboratories they once inhabited.

The opportunity to ban the bomb before the arms race took off was squandered not because the public failed to recognize the threat, but because the government refused to heed the will of its people.

As physicist Joseph Rotblat observed, among the many forms of collateral damage inflicted by the bomb was the destruction of “the ivory towers in which scientists had been sheltering.” In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that rupture propelled them into public life on an unprecedented scale. The once-firm boundary between science and politics began to blur as formerly quiet and aloof researchers spoke to the press, delivered public lectures, published widely circulated articles, and lobbied members of Congress in an effort to secure some control over atomic energy.

Among them was J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory where the bomb was created, who warned that, “if atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world… then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima,” a statement that left some officials perplexed. Former Vice President Henry Wallace, who had known Oppenheimer as both the director of Los Alamos and someone who had directly sanctioned the bombings, recalled that “he seemed to feel that the destruction of the entire human race was imminent,” adding, “the guilt consciousness of the atomic bomb scientists is one of the most astounding things I have ever seen.”

Yet the scientists pressed ahead in their frantic effort to avert future catastrophe by preventing a nuclear arms race. They insisted that there was no doubt the Soviet Union and other powers would acquire the weapon, that any hope of a prolonged atomic monopoly was delusional, and that espionage was incidental to such a reality, since the fundamental scientific principles needed to build an atomic bomb had been established by 1940. And with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the secret that a functioning bomb was possible was obviously out.

They argued that there would be no effective defense against a devastating atomic attack and that the US, as a highly urbanized society, was uniquely vulnerable to such “city killer” weapons. With vast, exposed coastlines, they warned that such a bomb, not yet capable of being delivered by a missile, could simply be smuggled into one of the nation’s ports and lie dormant there for years. For the scientists, the implications were unmistakable. The age of national sovereignty had ended. The world had become too dangerous for national chauvinism, which, if humanity were to survive, had to give way to a new architecture of international cooperation.

Teaching Us to Love the Bomb

Such activism had its intended effects. Many Americans became more fearful and wanted arms control. By late 1945, a majority of the public consistently supported some form of international control over such weaponry and the abolition of the manufacturing of them. And for a brief moment, such a possibility seemed within reach. The first resolution passed by the new United Nations in January 1946 called for exactly that. The publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima first as a full issue of the New Yorker and then as a book, with its intense portrayal of life and death in that Japanese city, further shifted public sentiment toward abolition.

Yet as such hopes crystallized at the United Nations, the two global superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were already preparing for a future nuclear war. Washington continued to expand its stockpile of atomic weaponry, while Moscow accelerated its work creating such weaponry, detonating its initial atomic test four years after the world first met that terrifying new weapon. That Soviet test, followed by the Korean War, helped extinguish the early promise of an international response to such weaponry, a collapse aided by deliberate efforts in Washington to ensure that the United States grew its atomic arsenal.

In that effort, former Secretary of War Henry Stimson was coaxed out of retirement by President Truman’s advisers who urged him to write one final, “definitive” account defending the bombings to neutralize growing opposition. As Harvard president and government-aligned scientist James Conant explained to Stimson, officials in Washington feared that they were losing the ideological battle. They were particularly concerned that mounting anti-nuclear sentiment would prove persuasive “among the type of person that goes into teaching,” shaping a generation less inclined to regard their decision as morally legitimate.

Stimson’s article, published in Harper’s Magazine in February 1947, helped cement the official narrative: that the bomb was a last resort rooted in military necessity that saved half a million American lives and required neither regret nor moral examination. In that way, the opportunity to ban the bomb before the arms race took off was squandered not because the public failed to recognize the threat, but because the government refused to heed the will of its people. Instead, it sought to secure power through nuclear weapons, driven by a paranoid fear of Moscow that became a self-fulfilling prophecy. What followed were decades of preemptive escalation, the continued spread of such weaponry globally, and, at its height, a global arsenal of more than 60,000 nuclear warheads by 1985.

Forty years later, in a world where nine countries—the US, Russia, China, France, Great Britain, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea—already have nuclear weapons (more than 12,000 of them), there can be little doubt that, as things are now going, there will be both more countries and more weapons to come.

Such a global arms race must, however, be ended before it ends the human race. The question is no longer what is politically possible, but what is virtually guaranteed if we refuse to pursue the “impossible.” Nuclear weapons are human creations, and what is made by us can be dismantled by us. Whether that happens in time is, of course, the question that now should confront everyone, everywhere, and one that history, if there is anyone around to write or to read it, will not excuse us for failing to answer.