SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"This was a bribe," said one critic.

A bombshell Saturday report from the Wall Street Journal revealed that a member of the Abu Dhabi royal family secretly backed a massive $500 million investment into the Trump family's cryptocurrency venture months before the Trump administration gave the United Arab Emirates access to highly sensitive artificial intelligence chip technology.

According to the Journal's sources, lieutenants of Abu Dhabi royal Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan signed a deal in early 2025 to buy a 49% stake in World Liberty Financial, the startup founded by members of the Trump family and the family of Trump Middle East envoy Steve Witkoff.

Documents reviewed by the Journal showed that the buyers in the deal agreed to "pay half up front, steering $187 million to Trump family entities," while "at least $31 million was also slated to flow to entities affiliated with" the Witkoff family.

Weeks after green lighting the investment into the Trump crypto venture, Tahnoon met directly with President Donald Trump and Witkoff in the White House, where he reportedly expressed interest in working with the US on AI-related technology.

Two months after this, the Journal noted, "the administration committed to give the tiny Gulf monarchy access to around 500,000 of the most advanced AI chips a year—enough to build one of the world’s biggest AI data center clusters."

Tahnoon in the past had tried to get US officials to give the UAE access to the chips, but was rebuffed on concerns that the cutting-edge technology could be passed along to top US geopolitical rival China, wrote the Journal.

Many observers expressed shock at the Journal's report, with some critics saying that it showed Trump and his associates were engaging in a criminal bribery scheme.

"This was a bribe," wrote Melanie D’Arrigo, executive director of the Campaign for New York Health, in a social media post. "UAE royals gave the Trump family $500 million, and Trump, in his presidential capacity, gave them access to tightly guarded American AI chips. The most powerful person on the planet, also happens to be the most shamelessly corrupt."

Jesse Eisinger, reporter and editor at ProPublica, argued that the Abu Dhabi investment into the Trump cypto firm "should rank among the greatest US scandals ever."

Democratic strategist David Axelrod also said that the scope of the Trump crypto investment scandal was historic in nature.

"In any other time or presidency, this story... would be an earthquake of a scandal," he wrote. "The size, scope and implications of it are unprecedented and mind-boggling."

Tommy Vietor, co-host of "Pod Save America," struggled to wrap his head around the scale of corruption on display.

"How do you add up the cost of corruption this massive?" he wondered. "It's not just that Trump is selling advanced AI tech to the highest bidder, national security be damned. Its that he's tapped that doofus Steve Witkoff as an international emissary so his son Zach Witkoff can mop up bribes."

Former Rep. Tom Malinkowski (D-NJ) warned the Trump and his associates that they could wind up paying a severe price for their deal with the UAE.

"If a future administration finds that such payments to the Trump family were acts of corruption," he wrote, "these people could be sanctioned under the Global Magnitsky Act, and the assets in the US could potentially be frozen."

In a speech before cheering supporters, Democrat Taylor Rehmet dedicated his victory "to everyday working people."

Democrats scored a major upset on Saturday, as machinist union leader Taylor Rehmet easily defeated Republican opponent Leigh Wambsganss in a state senate special election held in a deep-red district that President Donald Trump carried by 17 percentage points in 2024.

With nearly all votes counted, Rehmet holds a 14-point lead in Texas' Senate District 9, which covers a large portion of Tarrant County.

In a speech before cheering supporters, Rehmet dedicated his victory "to everyday working people" whom he credited with putting his campaign over the top.

This win goes to everyday, working people.

I’ll see you out there! pic.twitter.com/kPWzjn2LhW

— Taylor Rehmet (@TaylorRehmetTX) February 1, 2026

Republican opponent Wambsganss conceded defeat in the race but vowed to win an upcoming rematch in November.

“The dynamics of a special election are fundamentally different from a November general election,” Wambsganss said. “I believe the voters of Senate District 9 and Tarrant County Republicans will answer the call in November.”

Republican Texas Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick reacted somberly to the news of Rehmet's victory, warning in a social media post that the result was "a wake-up call for Republicans across Texas."

"Our voters cannot take anything for granted," Patrick emphasized.

Democratic US Senate candidate James Talarico, on the other hand, cheered Rehmet's victory, which he hinted was a sign of things to come in the Lone Star State in the 2026 midterm elections.

"Trump won this district by 17 points," he wrote. "Democrat Taylor Rehmet just flipped it—despite Big Money outspending him 10:1. Something is happening in Texas."

Steven Monacelli, special correspondent for the Texas Observer, described Rehmet's victory as "an earthquake of Biblical proportions."

"Tarrant County is the largest red county in the nation," Monacelli explained. "I cannot emphasize enough how big this is."

Adam Carlson, founding partner of polling firm Zenith Research, noted that Rehmet's victory was truly remarkable given the district's past voting record.

"The recent high water mark for Dems in the district was 43.6% (Beto 2018)," he wrote, referring to Democrat Beto O'Rourke's failed 2018 US Senate campaign. "Rehmet’s likely to exceed 55%. The heavily Latino parts of the district shifted sharply to the left from 2024."

Polling analyst Lakshya Jain said that the big upset in Texas makes more sense when considering recent polling data on voter enthusiasm.

"Our last poll's generic ballot was D+4," he explained. "Among the most enthusiastic voters (a.k.a., those who said they would 'definitely' vote in 2026)? D+12. Foreseeable and horrible for the GOP."

Bud Kennedy, a columnist for the Forth Worth Star-Telegram, argued that Rehmet's victory shows that "Democrats can win almost anywhere in Texas" in 2026.

Kennedy also credited Rehmet with having "the perfect résumé for a District 9 Democrat" as "a Lockheed Martin leader running against a Republican who had lost suburban public school voters, particularly in staunch-red Republican north Fort Worth."

The first thing officials in the Trump administration did after the fatal shootings of Renee Good and Alex Pretti was to blame them, not the trigger-happy ICE and Border Patrol agents nurtured by Trump’s scapegoating.

I don’t remember ever hearing federal officials so quickly, in unison, blame the victim as after the killing of Renee Good in Minneapolis on January 7 by an agent of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE. And as quick after the killing of Alex Pretti two weeks later on January 24 by agents of US Customs and Border Protection, or Border Patrol.

The Border Patrol before principally operated within 100 miles of the US border, hence its name. That changed with the so-called immigration enforcement by the Department of Homeland Security (“DHS”) under President Donald Trump. With the lines between ICE and Border Patrol blurred, when protesters shout “ICE Out,” they mean both.

Both killed Renee Good and Alex Pretti. That is, ICE’s transformation under the Trump administration led to their killing. A metamorphosis in which scapegoating is one motivating force to justify scaling up ICE and its deployment into the Twin Cities, tagged by DHS “Operation Metro Surge.” Victim blaming is one manifestation of the Trump administration’s overarching scapegoating propaganda machine.

German documentarian Neal McQueen reminds us of the poisonous functions of scapegoating in his comparison of the rise in Germany in the 1920s of the Nazi Party’s paramilitary force Sturmabteilung (often called “Brown Shirts”) and today’s ICE. “No moral equivalence is asserted,” he writes of his comparison. What he does do is highlight how both organizations, his words, “constructed their ideological purpose through scapegoating.”

Where was the mind of ICE and Border Patrol personnel shooting Alex Pretti and Renee Good? Was it the mindset of a paramilitary force in combat with those at odds with MAGA and its ideology?

Scapegoating is nothing new in the US. The Ku Klux Klan (“KKK”), one example, has been a paramilitary group supporting its purpose via scapegoating. As historian William Trollinger wrote, while “the original Klan concentrated its animus against the newly freed slaves and their Republican Party supporters,” the Klan growth in the 1920s relied upon an “expanded list of social scapegoats that included Catholics, Jews, and immigrants.”

But the KKK hasn’t been an armed force within the executive branch of the US government as is ICE. With ICE becoming more so with the ballooning funding and personnel expansion during President Trump’s second term.

President Trump has proven himself a master of using scapegoating to maintain and grow his political power, as Jess Bidgood at the New York Times chronicles. His targeting Somalis in the Twin Cities in Minnesota a latest example.

A video posted in December 2025 by a conservative YouTuber alleged fraud in some Somali-run childcare centers. Allegations refuted in follow-up investigation by the state. But damage done, as President Trump and his minions ramped up attributing fraud to all of Somali descent in Minneapolis-St. Paul, the majority American citizens.

What the video missed was actual fraud occurring during the Covid-19 pandemic. And the biggest fraudster then was the convicted white female founder of Feeding Our Future. That fraud involved providing a publicly-financed nutrition program with false counts and invoices of meals provided to children. Some of Somali descent participated in the fraud, but only around one-tenth of 1% of all Somalis in the Twin Cities.

Repeatedly we hear the focus of Trump’s immigration enforcement is deporting “the worst of the worst.” The word “worst” said referring to criminal and violent undocumented immigrants. But analysis at the Cato Institute indicates these are not the vast majority of immigrants being rounded up and deported. In practice, as America has witnessed in Minneapolis and elsewhere, “worst” means not being white.

Scapegoating is evident in the killing of Renee Good and Alex Pretti. In likely nurturing trigger-happy ICE and Border Patrol agents. And in blaming Ms. Good and Mr. Pretti.

Within two hours of Renee Good’s killing, the victim blaming started, as analysis by ABC News documents. A post on X by DHS stated Ms. Good “weaponized her vehicle, attempting to run over” ICE agents “in an attempt to kill them—an act of domestic terrorism.” And President Trump joined in with his own post that day writing:

The woman driving the car was very disorderly, obstructing and resisting, who then violently, willfully, and viciously ran over the ICE Officer… it is hard to believe he is alive, but is now recovering in the hospital.

Vice President J.D. Vance also jumped in, blaming Ms. Good, as did DHS Secretary Kristi Noem. All the victim-blaming lies, revealed as such in the video analysis by New York Times, that by the Guardian, and others.

When the officer shot through Ms. Good’s open driver-side window, he clearly wasn’t run over. Instead, he was positioned with Ms. Good as a target he couldn’t miss. And after all the shots were fired, you can hear him say “fucking bitch.” He then walked away, casually as if leaving a session at a shooting range proud to have hit the bullseye.

Looking at the video of Ms. Good’s killing, I can’t help but think the ICE agent already knew he had immunity before Vice President Vance announced it later that day. Knew when he shot with his gun pointed through the window at Ms. Good’s head.

A private autopsy performed for Ms. Good’s family revealed she was shot three times; in the breast, forearm, and head. The wounds of the breast and forearm were deemed not immediately fatal. But the head wound was deemed more immediately so.

And why was Ms. Good’s killer taking video of her license plate. Probably because he and other agents were told to collect identifying information on protesters; protesters joining an enemy list with Somalis. And, as should be expected, as in all wars enemies get killed.

Victim blaming continued with the killing of Alex Pretti. Border Patrol Commander Greg Bovino, held a news conference a few hours after this fatal shooting saying:

…an individual [Alex Pretti] approached US Border Patrol agents with a 9-millimeter semi-automatic handgun. The agents attempted to disarm the individual, but he violently resisted. Fearing for his life and the lives and safety of fellow officers, a border patrol agent fired defensive shots…This looks like a situation where an individual wanted to do maximum damage and massacre law enforcement.

And at her news conference the same day, DHS Secretary Noem’s victim blaming was identical word for word.

But video shows Alex Pretti did not brandish his legally-carried gun. Nor violently resist. With instead holding his hands up above his head, cell phone in one hand. What violence there was happened when Border Patrol agents threw him to the ground and held him down.

One agent appeared to step back with Mr. Pretti’s gun in his hand having removed it. Then gunfire heard. Not by one officer, but two. The first shots finding Mr. Pretti motionless lying face down. Then agents stepping back fired a rapid blast of more shots into Pretti’s still body, analysis indicating a total of 10 shots fired.

The preceding description is consistent with the moment-by-moment video analysis of Alex Pretti’s shooting by CNN. And, also, by ABC News and the New York Times. And with sworn testimonies of eye witnesses.

When I watched videos of Mr. Pretti’s killing, I couldn’t help but wonder how the agents felt when firing their rapid volley of bullets. Was it to them, as the scene intensely felt to me, like a moment of target practice as if at a shooting range?

Where was the mind of ICE and Border Patrol personnel shooting Alex Pretti and Renee Good? Was it the mindset of a paramilitary force in combat with those at odds with MAGA and its ideology? More that than of agents performing disciplined immigration enforcement?

Rep Jamie Raskin (D-Md.) seems to wonder that himself in his letter on January 12 to Attorney General Pamela Bondi and DHS Secretary Kristi Noems, writing:

DHS seems to be courting pardoned January 6th insurrectionists. It uses white nationalist “dog whistles” in its recruitment campaign for US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents that appear aimed at stirring members of extremist militias… which participated in the insurrection… ICE agents conceal their identities, wearing masks and removing names from their uniforms. Who is hiding behind these masks? How many of them were among the violent rioters who attacked the Capitol on January 6th and were convicted of their offenses [but Trump pardoned]?

Aside from recruitment messages already winking to extremists, Washington Post reported on future ICE recruitment plans (also discussed on Democracy Now) to reach attendees at, for instance, gun shows and NASCAR races among other venues.

After the killing of Mr. Pretti, the killing of Ms. Good not sufficient alone, President Trump said he was “de-escalating” the surge of ICE and Border Patrol agents into Minnesota “a little bit,” replacing Commander Greg Bovino with Trump’s “border czar” Tom Homan.

Then again, an ICE agent also told an observer in Minnesota just days after Alex Pretti was killed, “You raise your voice, I will erase your voice.”

His new dietary guidelines promoting saturated fats are a recipe for disaster, and a heart attack.

Fat is now phat, at least according to Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

When President Donald Trump’s Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary unveiled new federal dietary guidelines this January, he declared: “We are ending the war on saturated fats.” Seconding Kennedy was Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Marty Makary, who promised that children and schools will no longer need to “tiptoe” around fat.

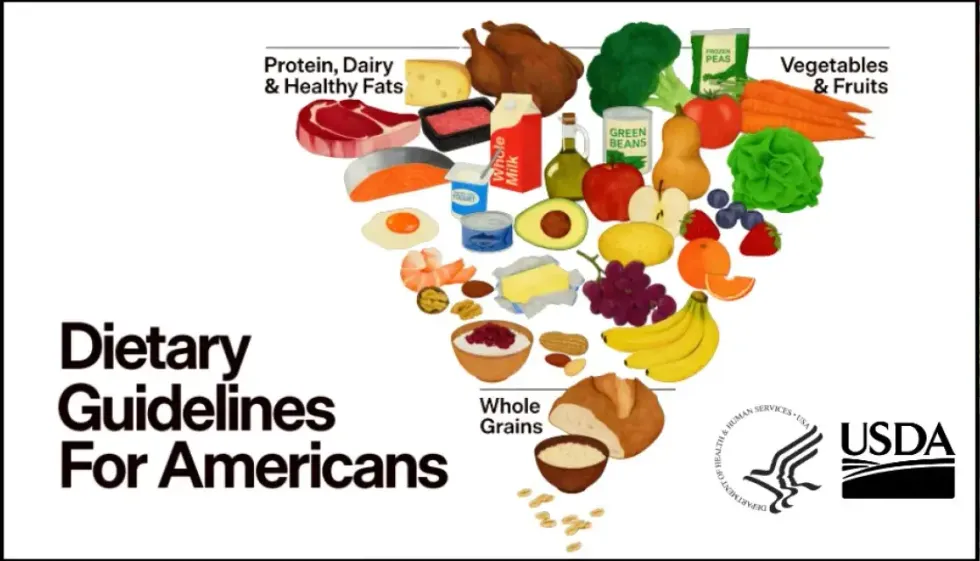

Kennedy’s exaltation of fat comes complete with a new upside-down guidelines pyramid where a thick cut of steak and a wedge of cheese share top billing with fruit and vegetables. This prime placement of a prime cut is the strongest endorsement for consuming red meat since the government first issued dietary guidelines in 1980.

The endorsement reverses decades of advisories, which the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and HHS jointly issue every five years, to limit red meat consumption issued under both Democratic and Republican administrations given the strong evidence that eating less of it lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease. Multiple studies over the last decade have linked red and processed meats not only to cardiovascular disease, but also to colon polyps, colorectal cancer, diabetes, diverticulosis, pneumonia, and even premature death.

Given the scientific evidence, we should intensify the war against saturated fats, not call it off.

The new dietary guidelines even contradict those issued under the first Trump administration just five years ago, warning Americans not to eat too much saturated fat. “There is little room,” those guidelines stated, “to include additional saturated fat in a healthy dietary pattern.” A significant percentage of saturated fat comes from red meat. Americans, who account for only 4% of the people on the planet, consume 21% of the world’s beef.

Kennedy’s fatmania even extends to beef tallow and butter, which the new pyramid identifies—along with olive oil—as “healthy fats” for cooking. In fact, beef tallow is 50% saturated fat. Butter is nearly 70%. Olive oil, meanwhile, is just 14% saturated fat and is, indeed, healthy.

This rendering of recommended fats muddles a message that could have been stunningly refreshing, given the Trump administration’s penchant for meddling with science. Some of the new pyramid’s recommendations were applauded by mainstream health advocacy groups, particularly one advising Americans to consume no more than 10 grams of added sugar per meal and others, as Kennedy pointed out, calling for people to “prioritize whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains—and dramatically reduce highly processed foods.”

But such wholesomeness could easily be wasted if Americans increase their meat consumption. That would not, as Kennedy professes, make America healthy again. Given the scientific evidence, we should intensify the war against saturated fats, not call it off.

The 420-page report by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee prepared in 2024 for the USDA and HHS found that more than 80% of Americans consume more than the recommended daily limit of saturated fat, which is about 20 grams—10% of a 2,000 calorie-per-day diet. The report concluded that replacing butter with plant-based oils and spreads higher in unsaturated fat is associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk and eating plant-based foods instead of meat is “associated with favorable cardiovascular outcomes.”

A March 2025 peer-reviewed study in JAMA Internal Medicine came to a similar conclusion. It found that eating more butter was associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Using plant-based oils instead of butter, the researcher found, was associated with a 17% lower risk of death. Such a reduction in mortality, according to study co-author Dr. Daniel Wang, means “a substantial number of deaths from cancer or from other chronic diseases … could be prevented” by replacing butter with such plant-based oils as soybean or olive oil.

What does a “substantial” number of deaths look like? Heart disease is the No. 1 killer in the United States, and heart disease and stroke kill more people than all cancers and accidents combined. The annual number of American deaths tied to cardiovascular disease is creeping toward the million mark. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), it killed more than 940,000 people in 2022.

Over the next 25 years, AHA projects that the incidence of high blood pressure among adults will increase from 50% today to 61%, obesity rates will jump from 43% to 60% and diabetes will afflict nearly 27% of Americans compared to 16% today. Reducing mortality by 17% for those and other related health problems would go a long way to make Americans healthier.

A good place to begin reducing food-related mortality is by cutting highly processed foods out of the American diet. That would require a drastic change in eating habits for a lot of people. A July 2022 study found that nearly 60% of calories in the average American diet comes from ultra-processed foods, which have been linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, and obesity.

One of the main culprits is fast food. A January 2025 study of the six most popular fast-food chains in the country—Chick-fil-A, Domino’s Pizza, McDonald’s, Starbucks, Subway and Taco Bell—found that 85% of their menu items were ultra-processed. And, according to a 2018 study, more than a third of US adults dine at a fast-food chain on any given day, including nearly half of those aged 20 to 39.

Our overreliance on fast food presents a huge conundrum. US food systems are structured in a way that it is unlikely you can tell people to cut processed foods and eat more meat at the same time. Hamburgers and processed deli meat are among the main ways Americans consume red meat. And given the blizzard of TV ads for junk food and fast-food joints, which have proliferated across the country and especially in low-income food deserts—it is also unlikely that many people will use the new guidelines to comb through their local grocer’s meat department for the leanest (and often most expensive) cut of beef.

According to the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health, food, beverage, and restaurant companies spend $14 billion a year on advertising in the United States. More than 80% of those ad buys are for fast food, sugary drinks, candy, and unhealthy snacks. That $14 billion is also 10 times more than the $1.4 billion fiscal year 2024 budget for chronic disease and health promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And don’t expect the CDC to get into an arms race with junk food advertisers any time soon. Kennedy slashed the CDC staff by more than 25%, from 13,500 to below 10,000.

All of this adds up to the probability that Americans will see the new guidelines’ recommendation to eat red meat as a green light to gorge on even more burgers and other fast-food, ultra-processed meat.

The new guidelines’ green light for consuming red meat and saturated fats is particularly vexing given the guidelines produced five years ago during Trump’s first term did not promote them. Why the about-face?

During the run-up to Trump’s second term, the agribusiness industry went into overdrive to install Trump in the White House and more Republicans in Congress. In 2016, agribusinesses gave Trump $4.6 million for his campaign, nearly double what it gave Hillary Clinton. But in 2024, they gave Trump $24.2 million, five times what it gave Kamala Harris. Agribusinesses also donated $1 million to Kennedy’s failed 2024 campaign, making him the fourth-biggest recipient among all presidential candidates during that election cycle.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is nowhere near making America healthy again by declaring in his new food pyramid that red meat is as healthy as broccoli, tomatoes, and beans.

Despite claiming he wanted dietary guidelines “free from ideological bias, institutional conflicts, or predetermined conclusions,” Kennedy rejected the recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee and turned over the nation’s dietary data to 9 review authors, at least 6 of whom had financial ties to the beef, dairy, infant-formula, or weight-loss industry.

Three of them have received either research grant funding, honoraria, or consulting fees from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, which is known for funding dubious research downplaying or dismissing independent scientific findings that show read meat to be threat to public health and the environment. In 2024, the trade group gave nearly all of its $1.1 million in campaign contributions to Republican committees and candidates.

Kim Brackett, an Idaho rancher and vice president of the beef industry trade group, hailed the new guidelines, claiming “it is easy to incorporate beef into a balanced, heart-healthy diet.”

Perhaps, but the grim reality is most Americans do not follow a balanced, heart-healthy diet. Four out of five of us are already consuming more than the recommended daily limit of saturated fat and we are well on our way to a 60% obesity rate.

So, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is nowhere near making America healthy again by declaring in his new food pyramid that red meat is as healthy as broccoli, tomatoes, and beans. Beholden to Big Beef, he is driving us full speed ahead on the road to a collective heart attack.

This article first appeared at the Money Trail blog and is reposted here at Common Dreams with permission.