Don't Call It a 'Bombshell'—Microplastics Science Is Doing Exactly What It Should

The biggest threat isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty used to delay regulations.

“Microplastics are everywhere, and they’re harming us.”

“Actually, maybe not.”

“Hold on, that study might be flawed.”

“Bombshell… the whole field is in doubt.”

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

If you’ve been hearing about microplastics recently, you may have been getting whiplash from the headlines. But you shouldn’t be.

Because this is what science looks like when it’s working: Researchers test new ideas and challenge each other’s methods. This helps refine what we know. What isn’t supposed to happen is a normal, healthy, scientific process getting manipulated into a dramatic storyline about a fictional scandal—a story that can leave the public confused.

The Myth Machine: How a Story We Tell Can Become a Trap

For over two decades, we’ve studied plastic pollution in the ocean. Scientists started describing the accumulation zones of plastic in the subtropical gyres, the places where wind and water currents concentrate floating debris. The research pointed to a truth that was complicated but clear: Most of the pieces are tiny, fragmented plastic—microplastics—along with some larger marine debris, like fishing gear.

But the media put a spin on it, and gave the world a simpler picture: a floating island of trash, “twice the size of Texas.” Some even called this a “garbage patch” you could supposedly walk on. People cried, “Why can’t I see it on Google Maps?” Some wondered if the US should plant a flag, and a handful of naive entrepreneurs fabricated fantastic ocean cleanup contraptions.

It was dramatic. Word spread. But eventually, it backfired.

All those who went looking for an island, didn’t find one. Instead they concluded, “It’s more like smog than a landfill,” and some pointed out, “Maybe it was exaggerated and the world had been duped.”

The pattern—one that goes oversimplify, sensationalize, backlash, dismissal—can drain urgency from a real crisis. Misinformation gets the headline. This gets repeated, as we’ve seen before in other environmental debates, such as the hole in the ozone layer, or climate change. The same thing is unfolding now with microplastics and human health.

What the “Bombshell” Reporting Gets Wrong

The recent article in The Guardian that sparked this debate focuses on a real issue. In our research studying microplastics in the environment and animal studies, measuring micro- and nanoplastics in human tissue is incredibly hard. It is particularly difficult when researchers are looking for very small particle sizes, where laboratory contamination from airborne sources becomes harder to rule out. This is especially the case in human tissue.

Microplastics are not like other contaminants, such as lead in water, where you can measure parts per billion, and lean on decades of standardized instruments and test methods. Plastics come in many polymers, sizes, and shapes. Nanoplastics behave differently than microplastics. And plastic is everywhere, meaning background contamination is always a risk. This is sometimes called the “pig pen effect”—it is a challenge to study a material that is so widespread.

The Guardian article is not a devastating blow. It’s a scientific debate around specific methods in a research field that is rapidly improving.

What’s the Real Headline?

The headline isn’t “microplastics in people might be wrong,” but rather “quantifying microplastics in human samples is challenging, and the science is evolving in the right direction.”

That difference matters. If the public hears “doubt cast,” then it translates it as “maybe plastic pollution isn’t really there or not that bad.” The question is, does it hold up across methods, across labs, across time?

So what has science taught us?

- Yes, we do have microplastics in our bodies. A number of peer-reviewed research shows that plastics, or plastic-associated signals, are present in human samples. Some findings claims will hold up better with time. That’s normal.

- Scientists criticize each other's studies. This is how science becomes more reliable over time. How methods get stress tested. By challenging assumptions, doing repeated studies, etc. weak studies get corrected or critiqued. In rare cases retracted. This isn’t chaos. It’s science.

- Some headlines are hype. Microplastics science is new enough that every new study can feel like a “first,” which incentivizes media toward shock value. But, when scientific findings revise our understanding, the correction isn’t “nothing to see here.” The correction should be that science is a self-improving enterprise.

- Scientists have been, and will continue revising the numbers. For example, early reporting suggested we each eat a “credit card” of plastic each week (subsequent studies estimated much less). Is that a bombshell? No, not really. And if it’s widely seen as such, it might suggest we should wait before we act (e.g., until every uncertainty is resolved). But, that’s not how public health works. We make decisions based on the best available science, and assess risk with limited data.

Weaponized Uncertainty

The biggest threat here isn’t scientific uncertainty, since there’s a considerable amount of scientific consensus that there is plastic in us. The biggest threat is weaponized uncertainty.

Environmental health has a predictable plot—when evidence starts piling up that a pollutant is harmful, a well-funded countermovement doesn’t always try to prove it’s safe. On the contrary, it tries to prove that the science is messy, uncertain, and “we need more data.”.

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking.

The industry has a playbook with favorite phrases, such as: “not conclusive,” “uncertain,” “scientists disagree,” “lack of consensus.” Disagreement in science is healthy. However, this (very routine) component of science can also become a winning political strategy used against science and public policy. Casting doubt can delay regulation.

Naomi Oreskes writes in Merchants of Doubt, “The industry had realized you could create the impression of controversy simply by asking questions.” That’s why our concern isn’t that researchers are debating methods. Our concern is that sensational headlines can warp debate, and give merchants of doubt an opportunity to skew public perception.

Red-Flag Language—It Should Make You Pause

We’re not asking journalists to avoid urgency. Plastic pollution is urgent. Certain phrases, however, may signal that you’re being pulled into a pattern of mythmaking, such as “bombshell,” or “debunked,” when what’s really happening is refinement. Those phrases shock and entertain, but do little to foster understanding.

What we actually need next is for the microplastics field to keep growing. Researchers across the board—from those that think studies are exaggerated to those that stand behind their research findings—are making calls for better lab protocols, contamination controls, reporting requirements, and inter-lab studies to validate results. These are unglamorous, but they’re what solidify early research findings into trusted science. A first-of-its-kind finding of plastic somewhere in the human body shouldn’t be framed like the final truth. It should be heralded as the beginning of a more complete picture.

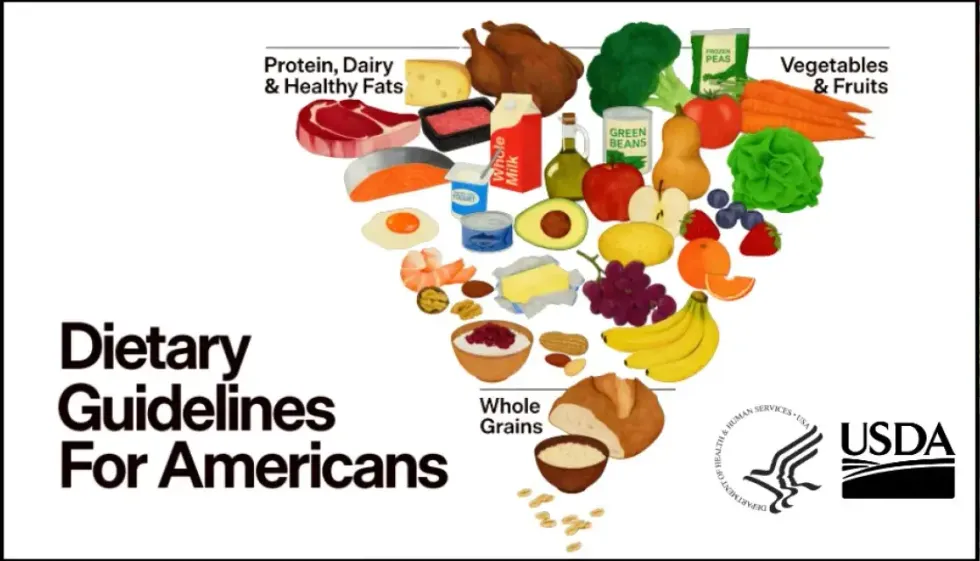

The new federal dietary guidelines reverse decades of advisories that recommended limiting red meat consumption. (Illustration: HHS/USDA)

The new federal dietary guidelines reverse decades of advisories that recommended limiting red meat consumption. (Illustration: HHS/USDA)