80 Years Ago, A Jewish Radical and Two Negro League Stars Led a Crusade to Integrate Baseball That Paved the Way for Jackie Robinson

The little known story about Sam Nahem, Leon Day, and Willard Brown who in 1945 played on a field in the shadow of Adolph Hitler's Nazi Germany and broke down historic barriers.

Eighty years ago this week—on September 8, 1945—a little-known episode in the struggle to challenge racial segregation took place in, of all places, Germany’s Nuremberg Stadium, where Adolf Hitler had previously addressed Nazi Party rallies. It was led by Sam Nahem, a left-wing Jewish pitcher who had a brief career in the major leagues, and included two Negro League stars, Leon Day and Willard Brown, who, like other African Americans, were banned from major league teams.

Their efforts were part of the wider “Double Victory” campaign during the war to beat fascism overseas and racism and anti-Semitism at home.

For more than a decade before Jackie Robinson broke the sport’s color line in 1947, black newspapers, civil rights groups, progressive white activists and sportswriters, labor unions, and radical politicians waged a sustained protest movement to end Jim Crow in baseball. They believed that if they could push the nation’s most popular sport to dismantle its color line, they could make inroads in other facets of American society. They picketed at big league ballparks, wrote letters to team owners and Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis demanding tryouts for Black athletes, and interviewed white players and managers, most of whom expressed a willingness to integrate major league rosters. Most white newspapers ignored the Negro Leagues, but black newspapers (and the Communist Party’s Daily Worker) covered their stars and games, including exhibition contests between Black teams and teams comprised of white major leaguers, many of which were won by Negro League players.

Nahem’s parents immigrated to America from Aleppo, Syria in 1912. Born in New York City in 1915, Nahem, one of eight siblings, grew up in a Brooklyn enclave of Syrian Jews. He spoke Arabic before he learned English.

Nahem demonstrated his rebellious streak early on. When he was 13, Nahem reluctantly participated in his Bar Mitzvah ceremony, but refused to continue with Hebrew school classes after that because “it took me away from sports.” To further demonstrate his rebellion, that year he ended his Yom Kippur fast an hour before sundown. Recalling the incident, he called it “my first revolutionary act.”

The next month—on November 12, 1928—Nahem’s father, a well-to-do importer-exporter, traveling on a business trip to Argentina, was one of over 100 passengers who drowned when a British steamship, the Vestris, sank off the Virginia coast. Within a year, the Great Depression had arrived, throwing the country into turmoil. With his father dead, Nahem’s family could have fallen into destitution.

“Fortunately we sued the steamship company and won enough money to live up to our standard until we were grown and mostly out of the house,” Nahem recalled. He remembered how, at age 14, he “used to haul coal from our bin to relatives who had no heat in the bitterly cold winters of New York.” So, despite his family’s own relative comfort, “I was quite aware of the misery all around.” That reality, Nahem remembered, “led to my embracing socialism.”

Education was Nahem’s ticket out of his insular community and into the wider world of sports and politics. In the early 1930s, he enrolled at Brooklyn College. The campus was a hotbed of radicalism. Like a significant number of his classmates, Nahem joined the Communist Party, but he primarily focused his time and energy on sports and his literature classes. He was a star pitcher for Brooklyn College’s baseball team and a highly-regarded fullback on its football team, gaining attention from the New York newspapers and baseball scouts.

Signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1935, after his sophomore year, he spent several years in the minor leagues, where he confronted anti-Semitism among his teammates and other players.

“I was aware I was a Jewish player and different from them. There were very few Jewish players at the time,” Nahem said. (There were only 10 Jews on major league rosters in 1938, Nahem’s rookie year.)

“Many of them came from where they probably had never met a Jewish person. You know, they subscribed to that anti-Semitism that was latent throughout the country. I fought it whenever it appeared.”

Because he was from New York, someone gave him the nickname “Subway Sam” while he played in the minors, and it stuck throughout his baseball career. During the off-seasons, Nahem, a voracious reader, earned a law degree at St. John’s University. He passed the bar in December 1938.

Two months earlier, he made his major league debut on October 2, 1938, the last day of the season. The 22-year old Nahem pitched a complete game to beat the Phillies 7-3 on just six hits. He also got two hits in five at bats and drove in a run.

Despite his stellar start, the Dodgers sent Nahem back to the minors, then traded him to the Cardinals, who assigned him to their minor league team in Houston and brought him up to the big league club the next season. In his first starting assignment for the Cardinals, on April 23, 1941, Nahem pitched a three-hitter, beating the Pittsburgh Pirates 3 to 1. That season, Nahem won five games, lost two, and registered an outstanding 2.98 earned run average.

Despite that performance, the Cardinals sold Nahem to the Philadelphia Phillies before the 1942 season. He made 35 appearances, posting a 1-3 won-loss record and a 4.94 ERA.

Like most radicals in those years, Nahem believed that baseball should be racially integrated. In both the minor and major leagues, he talked to teammates to encourage them to be open-minded.

“I did my political work there,” he told an interviewer years later. “I would take one guy aside if I thought he was amiable in that respect and talk to him, man to man, about the subject. I felt that was the way I could be most effective."

Nahem entered the military in November 1942. He volunteered for the infantry and hoped to see combat in Europe to help defeat Nazism. But he spent his first two years at Fort Totten in New York, where he pitched for the Anti-Aircraft Redlegs of the Eastern Defense Command. In 1943 he set a league record with a 0.85 earned run average, finished second in hitting with a .400 batting average, and played every defensive position except catcher. In September 1944, he and his Ft. Totten team beat the major league Philadelphia Athletics 9-5 in an exhibition game.

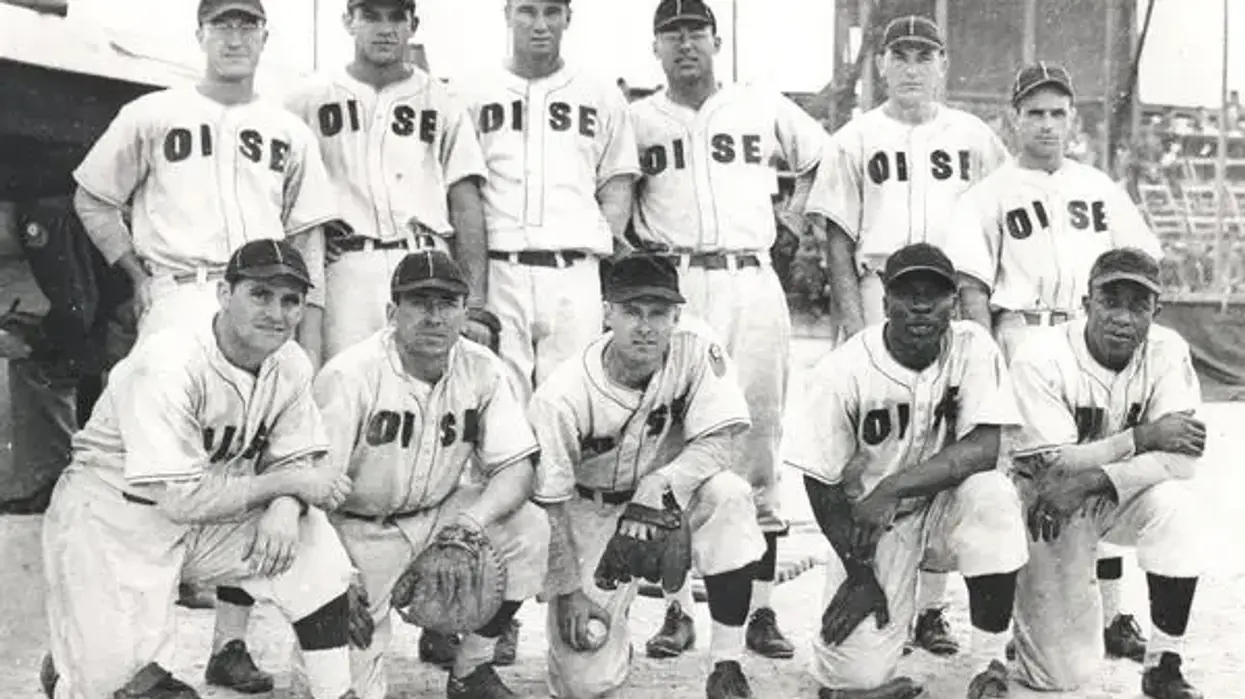

Sent overseas in late 1944, Nahem served with an anti-aircraft artillery division based in France. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, the American military expanded its baseball program. Over 200,000 troops, including many professional ballplayers, played on American military teams in France, Germany, Belgium, Austria, Italy, and Britain. Nahem, based in Rheims, France, managed and played for a team that represented the army command in charge of communication and logistics, headquartered in Oise, an administrative department located in the northern part of the country.

The team was called the OISE All-Stars. Besides Nahem, only one other OISE player, Russ Bauers, who had pitched for the Pittsburgh Pirates, had major league experience. The rest of the team was comprised mainly of semi-pro, college, and ex-minor-league players who were so little-known that news stories simply identified them by their hometowns.

Many top Negro League ballplayers were in the military, but they faced segregation, discrimination and humiliation, at home and overseas, assigned to the dirtiest jobs and typically living in separate quarters from white soldiers. Most black soldiers with baseball talent, including Jackie Robinson, were confined to playing on all-black military teams.

Monte Irvin, a Negro League standout who later starred for the New York Giants, recalled: “When I was in the Army I took basic training in the South. I’d been asked to give up everything, including my life, to defend democracy. Yet when I went to town I had to ride in the back of a bus, or not at all on some buses.”

Although the military was segregated during the war, some white and Black soldiers found opportunities to form friendships across the color line, or at least had enough exposure to challenge stereotypes and biases. Despite pervasive racism, some interracial camaraderie developed out of necessity or shared experiences. During the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944, for example, a shortage of infantrymen led General Dwight D. Eisenhower to temporarily desegregate units. Black and white soldiers fought alongside each other, and their teamwork on the battlefield was often better than expected. For many, these encounters helped shift opinions when they returned to their normal lives after the war. In addition, civilians in many European countries extended hospitality and friendship to Black Americans, which was the first time they felt welcome and equal among whites.

Defying the military establishment and baseball tradition, Nahem insisted on having African Americans on his team. He recruited Willard Brown, a slugging outfielder with the Kansas City Monarchs, and Leon Day, a star pitcher for the Newark Eagles, both of whom were stationed in France after the war in Europe ended.

In six full seasons before he joined the military, Brown, who grew up in Shreveport, Louisiana, led the Negro leagues in hits six times, home runs four times, and RBIs five times, batting between .338 and .379. Brown participated in the Normandy invasion as part of the Quartermaster Corps, hauling ammunition under enemy fire and guarding prisoners.

Day, who grew up in segregated Baltimore, was the Negro League’s best hurler with the exception of Satchel Paige and helped the Monarchs win five pennants. In 1942, he set a Negro League record by striking out 18 Baltimore Elite Giants batters in a one-hit shutout. Day also saw action in the Normandy invasion as part of the 818th Amphibian Battalion. He drove a six-wheel drive amphibious vehicle (known as a duck) that carried supplies ashore.

Nahem’s OISE team won 17 games and lost only one, and reached the European Theater of Operations (ETO) championship, known as the G.I. World Series. The opposing team, the 71st Infantry Red Circlers, represented General George Patton’s 3rd Army. One of Patton’s top officers assigned St. Louis Cardinals All-Star outfielder Harry Walker, a segregationist from Alabama, to assemble a team and pulled strings to get top major league players on its roster—even lending him a plane to bring players to the games. Besides Walker, the Red Circlers included seven other major leaguers, including Cincinnati Reds’ 6-foot-6 inch sidearm pitcher Ewell “the Whip” Blackwell.

The GI World Series took place in September, a few months after the U.S. and Allies had defeated Germany. Few people gave Nahem’s OISE All-Stars much chance to win against the hand-picked Red Circlers.

They played the first two games in Nuremberg. Allied bombing had destroyed the city but somehow spared the stadium, where Hitler spoke to huge rallies of Nazi followers, highlighted in Leni Riefenstahl’s infamous propaganda film, “Triumph of the Will.” The U.S. Army constructed a baseball diamond within the stadium and renamed it Soldiers Field.

On September 2, 1945, Blackwell pitched the Red Circlers to a 9-2 victory in the first game of the best-of-five series in front of 50,000 fans, most of them American soldiers. In the second game, Day held the Red Circlers to one run. Brown drove in the OISE team’s first run, and then Nahem (who was playing first base) doubled in the seventh inning to knock in the go-ahead run. OISE won the game 2-1. Day struck out 10 batters, allowed four hits and walked only two hitters.

The teams flew to OISE’s home field in Rheims for the next two games. The OISE team won the third game, as the New York Times reported, “behind the brilliant pitching of S/Sgt Sam Nahem,” who outdueled Blackwell to win 2-1, scattering four hits and striking out six batters. In the fourth game, the 3rd Army’s Bill Ayers, who had pitched in the minor leagues since 1937, shut out the OISE squad, beating Day by a 5-0 margin.

The teams returned to Nuremberg for the deciding game on September 8. Nahem started for the OISE team, again in front of over 50,000 spectators. After the Red Circlers scored a run and then loaded the bases with one out in the fourth inning, Nahem took himself out and brought in pitcher Bob Keane, who got out of the inning without allowing any more runs and completed the game. The OISE team won the game 2-1. The Sporting News adorned its report on the final game with a photo of Nahem.

Back in France, Brigadier Gen. Charles Thrasher organized a parade and a banquet dinner, with steaks and champagne, for the OISE All-Stars. In Victory Season, about baseball during World War 2, Robert Weintraub noted: “Day and Brown, who would not be allowed to eat with their teammates in many major-league towns, celebrated alongside their fellow soldiers.”

Although major white-owned newspapers, and the wire services, covered the GI World Series, no publication even mentioned the historic presence of two African Americans on the OISE roster. Almost every article simply referred to Day and Brown by name and position, but not by race or their Negro League ties. One exception was Stars & Stripes, the armed forces newspaper, which in one article described Day as “former star hurler for the Newark Eagles of the Negro National League,” and Brown as “former Kansas City Monarchs outfielder,” hinting at their barrier-breaking significance.

If there were any protests among the white players, or among the fans—or if any of the 71st Division’s officers raised objections to having African American players on the opposing team—they were ignored by reporters.

It isn’t known if Brooklyn Dodgers president Branch Rickey was aware of this triumph over baseball segregation in the military. But in October 1945, a month after the OISE team won the GI World Series, Rickey announced that Jackie Robinson had signed a contract with the Dodgers. In April 1947, Robinson became the first African American player in the modern major leagues.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981, which mandated the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces, including equality of treatment and opportunity regardless of race, color, religion, or national origin.

After the war, Nahem returned to Brooklyn and played baseball on weekends for a top-flight semi-pro team, the Brooklyn Bushwicks, who often played and beat the best Negro League teams and sometimes even defeated teams comprised of major league All-Stars. In October 1946, Nahem captained the Bushwicks team that represented the U.S. at the Inter-American Tournament in Venezuela. Nahem led the team to the championship, including winning the final game over Cuba. He remained in Venezuela to play for Navegantes del Magallanes, a racially integrated team in the professional winter league, pitching 14 consecutive complete games to set a league record that still stands today.

In 1948, Nahem got a second fling in the majors, but he lasted only one season with the Phillies. In one game, he threw an errant pitch that almost hit Roy Campanella, the Dodgers’ African American rookie catcher.

“He had come up that year and had been thrown at a lot, although there was absolutely no reason why I would throw at him,” Nahem later explained. “A ball escaped me, which was not unusual, and went toward his head. He got up and gave me such a glare. I felt so badly about it I felt like yelling to him, ‘Roy, please, I really didn’t mean it. I belong to the NAACP.”

Nahem pitched his last major league game on September 11, 1948. In his four partial seasons in the majors, he logged a 10–8 won-loss record and a 4.69 ERA. After leaving the Phillies, Nahem pitched briefly in the Puerto Rican League, then rejoined the Bushwicks for the 1949 season.

Nahem worked briefly as a law clerk but was never enthusiastic about pursuing a legal career. He took jobs as a door-to-door salesman and as a longshoreman unloading banana boats on the New York docks. The FBI kept tabs on Nahem, as it did with many leftists during the 1950s Red Scare. Agents would show up at his workplaces and tell his bosses that he was a Communist. He lost several jobs as a result.

To escape the Cold War witch-hunting, and to start life anew, Nahem, his wife Elsie, and their children moved to the San Francisco area in 1955. Nahem got a job at the Chevron fertilizer plant in Richmond, owned by the giant Standard Oil Corporation. During most of his 25 years at Chevron, he worked a grueling schedule — two weeks on midnight shift, two weeks on day shift, then two weeks on swing shift. He left the Communist Party in 1957, but he remained an activist. He served as head of the local safety committee for the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers union at the Richmond plant. Nahem was often offered management positions, but he refused to take them, preferring to remain loyal to his coworkers and his union. As late as 1961, the FBI kept Nahem under surveillance, according to his FBI file.

In 1969, he lead a strike among Chevron workers that attracted support from the Berkeley campus radicals. Nahem died in 2004 at 88.

Upon his release from the military, Day returned to the Newark Eagles, leading the Negro Leagues that season in wins, strikeouts, and complete games. Alongside other WW2 veterans Larry Doby, Monte Irvin, and Max Manning, he lead the team to the 1946 Negro League World Series. Day spent two years playing in the Mexican League for better pay, then spent the 1949 season with the Baltimore Elite Giants, helping them win the Negro World Series.

Day spent the rest of his baseball career in the minor leagues. In 1951, when he was 34 and well past his prime, he pitched for the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Triple-A International League. He retired in 1955 at age 39, then found work as a bartender and security guard. Day was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame on March 7, 1995, but he had been admitted to St. Agnes Hospital in Baltimore with a heart condition a few days earlier and died on March 14, at aged 78, and thus unable to attend his induction in Cooperstown. (Negro League players were banned from the Hall of Fame until 1971).

After the war, a few months after Jackie Robinson broke the major league color barrier, the American League’s St. Louis Browns signed Brown for the 1947 season. Despite becoming the first Black player in the league to hit a home run, he was a bust, batting only .179 in 21 games. The Browns let him go and he returned to the Monarchs for the 1948 season. For the next decade, he played in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic and in minor and independent leagues. When his playing days ended, Brown retired to Houston. He suffered from Alzheimer’s disease for several years and died in 1996 at age 81. He was elected posthumously to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2006.

Understandably, most Americans know about Jackie Robinson’s feats inside and outside of baseball. Almost forgotten are the Jewish Communist who had been an average major league pitcher and two Negro League superstars who were banned from major league baseball during their peak years. They, too, played a part in the crusade to battle racial injustice.