Remembering What Rev. Jesse Jackson Did for Palestinian Rights

Jackson was the first American political leader to recognize and incorporate into his movement my community of Arab Americans and our domestic and foreign policy concerns.

Rev. Jesse Jackson, who passed away last week, was a larger-than-life figure who made enormous and consequential contributions to American life. He registered millions of voters laying the groundwork for a substantial increase in the number of Black elected officials across the country. He also succeeded in pressing major corporations to increase economic opportunities for Black Americans thereby significantly increasing the Black middle class.

As part of the younger generation of Black leaders who had developed a global consciousness, his agenda moved beyond civil rights to make support for movements for social justice and liberation part of the mainstream of American politics. Because of this, he was the first American political leader to recognize and incorporate into his movement my community of Arab Americans and our domestic and foreign policy concerns.

I first began working with Rev. Jesse Jackson in the late 1970s. His staff approached me to discuss his plans for a visit to Palestine-Israel to see for himself the situation in the occupied lands. The injustices he witnessed left an indelible impression, leaving him committed to addressing the centrality of Palestinian rights to Middle East peace.

In 1979, when US Ambassador to the United Nations Andrew Young was removed from his post for speaking with the Palestine Liberation Organization’s United Nations representative, many Black leaders, Reverend Jackson included, were outraged. It wasn’t just that Andy Young had been a colleague in the civil rights movement. Jackson could not accept that the US had committed itself to a “no talk” policy with the Palestinian leaders.

In all the years I worked with Rev. Jackson, I witnessed not only his commitment to justice and courage in the face of challenges, but also the extent to which he recognized that his personal power could make a difference on the world stage.

He resolved to visit Beirut to meet directly with PLO chief Yasser Arafat and demonstrate that “a no talk policy is no policy at all.” Before leaving, he asked to address my Palestine Human Rights Campaign convention, taking place at that time. His presence and his remarks were electrifying and drew national and international media coverage.

In 1983 Rev. Jackson approached me at a dinner and asked me to leave what I was doing and join his campaign for president. When I replied, “I’ve been organizing my community of Arab Americans for the last four years and I’m not sure I can leave what I’m doing,” he said, “You will do more for your community in the next four months than you’ve done in the last four years.” He was right.

Up until that point, Arab Americans had never been welcomed in American politics as an ethnic constituency, mainly because of our support for Palestinian human rights. Candidates had rejected our contributions and endorsements. No campaign had ever included an Arab American committee. And no candidate had raised the issues about which our community cared deeply.

Rev. Jackson changed all that, and the response from Arab Americans was overwhelming. In fact, we were so moved by that 1984 campaign, that we launched the Arab American Institute to focus on lessons we’d learned: increasing voter registration, encouraging candidate engagement, and the importance of bringing our concerns into the electoral arena.

Because Rev. Jackson had made it possible to speak about Palestine, we built coalitions around the issue during the 1988 presidential campaign. We elected a record number of delegates across the country, and built coalitions with Black, Latino, progressive Jewish delegates, and others. We passed resolutions supporting Palestinian rights in 10 state Democratic conventions. And at the national convention in Atlanta, we’d earned enough delegates to call for a minority plank on Palestinian rights.

There had never been a discussion about Palestine at a Democratic convention. In negotiations with the presumptive winner Michael Dukakis’s campaign, they were adamant that the issue would not be raised. In fact, Madeleine Albright, representing the Dukakis people, said if the “P word” was even mentioned at the convention, “all hell would break loose.” I told them not to play “chicken little” with us and insisted that the issue be discussed. Rev. Jackson asked me to present our plank from the podium of the convention and I did. It was a heady experience to be able to address the National Convention calling for “mutual recognition, territorial compromise, and self-determination for both Israelis and Palestinians.” My speech was preceded by a floor demonstration of more than 1000 delegates carrying signs calling for Israeli-Palestinian peace and a two-state solution and waving Palestinian flags. It was the first (and unfortunately, the last) time that that issue was raised at a party convention.

The backlash was intense. While Rev. Jackson had secured a position for me on the Democratic National Committee, party leaders told me I should withdraw because my presence would make me a target for Republicans and for some Jewish Democrats, who would use an Arab American in a DNC leadership role to attack Dukakis. Incoming Party Chair Ron Brown thought it best that I withdraw but promised to make it up to us. And he did. He became the first party chair to host Arab Americans at party headquarters, to meet with Arab American Democrats around the country, and to address our national conventions. A few years into his term, he appointed me to fill a vacancy on the DNC where I’ve been ever since.

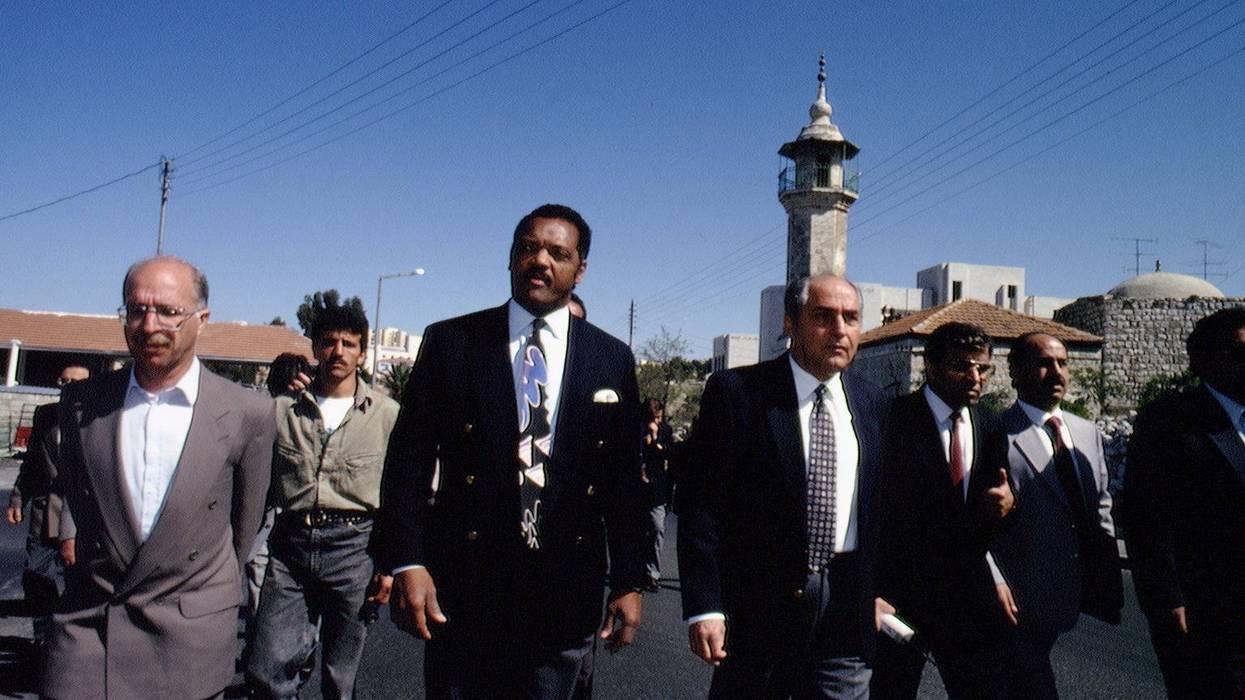

In 1994 in the months after Oslo Accords signing, Rev. Jackson accepted an invitation to be keynote speaker at an international peace conference the Palestinians were convening in Jerusalem. Once there, the Israelis said that we could not meet in Jerusalem or hold a political meeting with Palestinians. Rev. Jackson was determined to go forward. We spoke with Prime Minister Yitzak Rabin and Foreign Minister Shimon Perez urging them to allow the event to go forward. Even though they were unrelenting, Jackson convened the meeting and then announced that we’d march from the hotel to the Orient House, the Jerusalem headquarters of the Palestinians. The Israeli military surrounded the hotel and told us we could not leave.

True to form, Rev. Jackson announced that we’d march anyway and so we left the hotel walking through the lines of Israeli soldiers. To be honest, I was frightened, but what happened surprised us. Because of the power of his personality and his work, Jackson’s presence was formidable on the world stage. Once the Israelis soldiers saw him leading this peaceful march right up to their blockade, they parted and not only allowed him through, but many gathered around, wanting to touch or shake his hand, asking to have their pictures taken with him. The Israeli commanders were furious and continued barking orders to their troops to back away. The soldiers ignored them. We marched to Orient House and had our meeting.

In all the years I worked with Rev. Jackson, I witnessed not only his commitment to justice and courage in the face of challenges, but also the extent to which he recognized that his personal power could make a difference on the world stage. He freed prisoners. He opened doors to negotiations. He gave hope to the hopeless and voice to the voiceless. He also challenged the Democratic Party to be principled and consistent in its commitment to human rights and justice. He will be missed, but his legacy lives on in the progressive movement for domestic and foreign policy change that he helped shape.

(Photo by Statista/CC BY-ND 4.0)

(Photo by Statista/CC BY-ND 4.0)