What Zohran Mamdani’s Victory Tells Us About America

People across the country need leaders who will stand with them and fight for them with bold ideas that create real solutions for real problems.

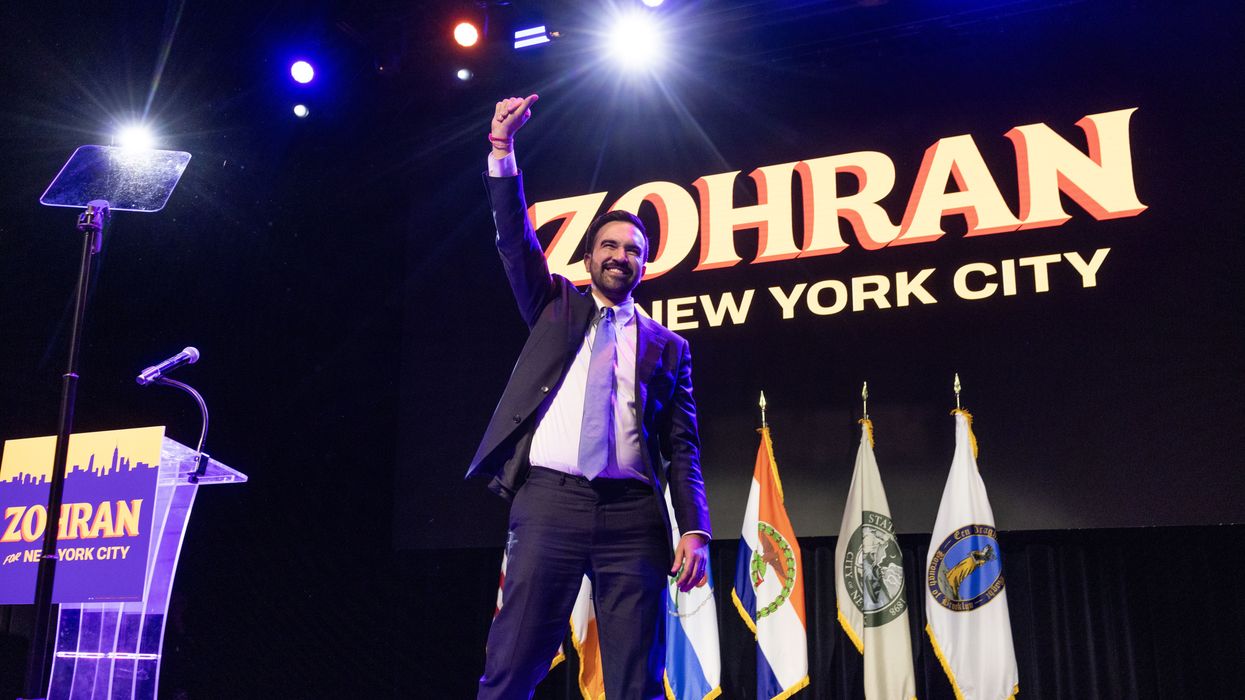

On a crisp November night, I stood shoulder to shoulder at the Brooklyn Paramount Theater with ecstatic New Yorkers celebrating Zohran Mamdani’s victory to become New York City’s first Muslim and South Asian mayor. The ornate hall was filled with people of all races, ethnicities, genders, and ages. I saw elderly South Asian men dancing, young people cheering, women in hijabs and trans women in saris. The venue was filled with hope and promise, and the audience represented the multicultural and multiracial ideals that make America great.

For New Yorkers and millions of people who have felt the political weight of the past years, Mamdani’s ascendance to Gracie Mansion is more than a victory; it is a cultural and emotional reckoning. The current events of the past few years have alienated so many people from politics, but on election night, it was clear that the energy has shifted. Mamdani has ushered in a new generation of politics, one that does not divide across race, religion, or age, but one that brings people together to drive change on the issues that impact their lives.

As a first-generation Muslim immigrant, I felt the November air fill with joy, hope, and an abundance of possibilities. As the CEO of a Muslim voter mobilization organization, I saw how hard the Muslim community worked for this moment, and I recognized the need for leaders like Mamdani and Ghazala Hashmi, who won her race to become Virginia’s first-ever Muslim and South Asian lieutenant governor.

I lead a team of primarily young US-born Muslim Americans, many of whom were born and raised against the backdrop of 9/11. They never lived in an America that embraced their Muslim identities. Yet, they still choose to become activists and organizers working to build a more inclusive and representative America and counter the political machines that demonized them, their families, and their neighbors—both at home and abroad.

New Yorkers showed us that hope and positivity can still win over hate and divisiveness.

Without a doubt, America changed after 9/11, and it slid toward authoritarianism that was largely fueled by rabid anti-Muslim bigotry. Elected officials sought to blame an entire American community for the actions of a few foreigners and waged forever wars that have continued to harm and destabilize entire nations decades later.

Even in today’s Trump era, the America that welcomed me and my family in 1988 from Syria no longer celebrates multiculturalism and the freedom of speech, and it is certainly not seeking peace and justice. Instead, it has continued the war machine of administrations past and fueled new wars against immigrants on American soil.

The election of Donald Trump in 2024 seemed to cement our descent toward isolationism and cruelty—indeed, we are sliding. From the weaponization of Immigration and Customs Enforcement against immigrant communities to the assault against the media to the unabashed corruption and cronyism, American democracy has been severely damaged.

But in the midst of all of this, in the age of Trump 2.0, a young, South Asian man who is unapologetically Muslim was elected mayor of America’s largest city. How could this happen, and what does it tell us about our country? The answer lies in both Mamdani’s platform and in our identity as a nation.

Mamdani’s campaign redefined grassroots organizing, political strategy, and digital outreach. He ran a disciplined and creative campaign that stayed on message no matter what his critics said: Make New York City affordable for all. He spoke the language of unity as his opponents relied on fearmongering and scare tactics. He brought people together under the belief that every day New Yorkers could be agents of change to create the city that they deserve.

Mamdani’s call for affordability was not just a campaign slogan; it was a collective affirmation of what New York City could be. He resonated with voters who are desperately struggling with unaffordable housing, food insecurity, inaccessible transportation, an overburdened healthcare system, and the exorbitant cost of childcare. These issues are not just top of mind for New Yorkers—they are indicative of what most Americans are struggling with. Mamdani remained laser focused on kitchen table issues and committed to a future that cared about the working class. Mamdani transcended his identity and connected directly with everyday people.

But identity does matter, especially for a Muslim-American in New York City. Despite Mamdani’s best efforts to focus on the issues central to his platform, he was forced to confront what his identity meant to the mayoral race—and most importantly, to himself. In the midst of perhaps the ugliest anti-Muslim campaign that we have ever seen directed at a public figure, Mamdani spoke clearly about his values that are grounded in his faith and how it taught him to care for others. He refused to hide it and plainly asked New York to embrace him for who he is. And New York responded with an emphatic yes.

The movement that Mamdani galvanized by meeting everyday New Yorkers where they were led to the highest turnout of voters in a mayoral election since 1969, surpassing all expectations. Over 1 million voters essentially rejected the smears and rose above the hate. They too stayed focused on the issues that actually mattered. New Yorkers showed us that hope and positivity can still win over hate and divisiveness. New Yorkers also showed us that voters can not be bought by deep-pocketed billionaires but can be brought together without demonizing and dehumanizing one another.

Most importantly, Mamdani’s victory showcased that people are hungry for change. We can no longer move forward with politics as usual. Americans across the country need leaders who will stand with them and fight for them. Americans need leaders with bold ideas that create real solutions for real problems.

Past leaders have shown us that America can turn on the people who make this country great. But on November 4, we saw that America is equally capable of producing leaders like Mamdani who fight for the common good.