'Yankees Go Home!' Colombians Demand at Mass Protests Against Trump Threats

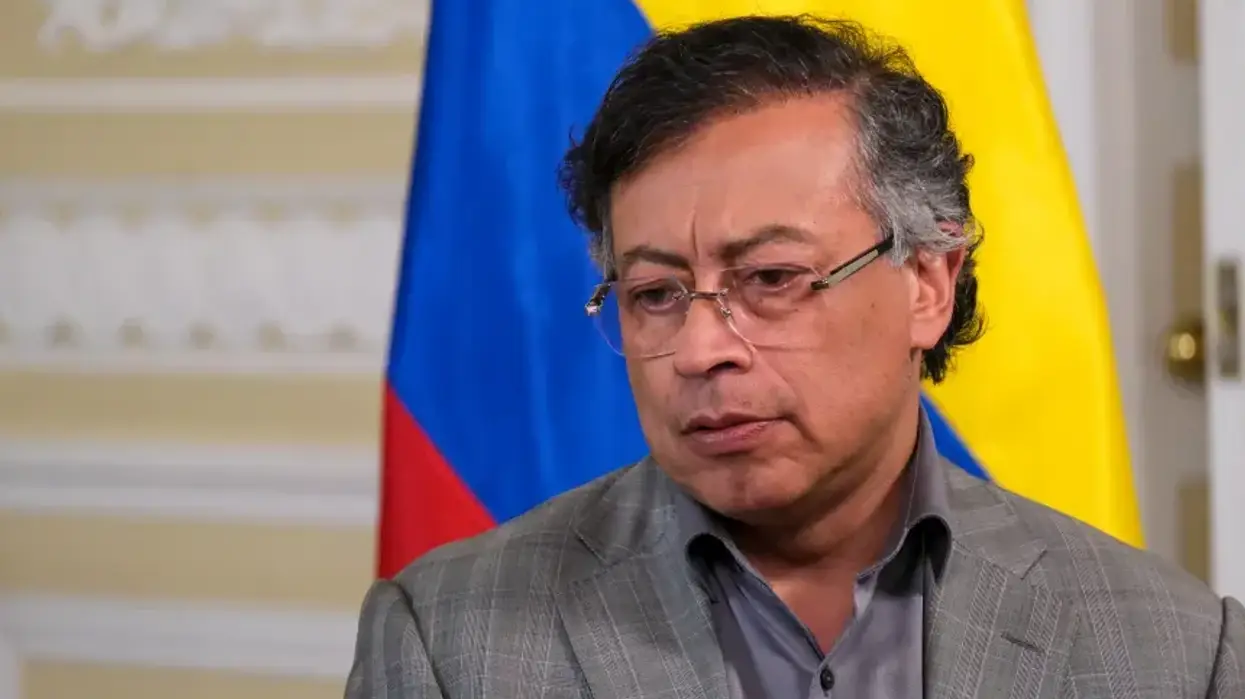

Thousands of people across the country expressed support for their president, Gustavo Petro, who spoke to President Donald Trump ahead of the rallies and struck a diplomatic but defiant tone.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro struck a relatively diplomatic tone Wednesday at a rally in Bogotá, where he spoke about the Trump administration's threats to launch military strikes against his country—but thousands of people who gathered in the Colombian capital and across the country were happy to say exactly what they thought of US President Donald Trump's recent attack on neighboring Venezuela and his saber-rattling across Latin America.

"He’s a maniac,” 67-year-old José Silva told the Guardian at a march in the border city of Cúcuta. “The US Congress needs to do something to get him out of the presidency... He’s a thug.”

“Trump is the devil," another marcher, Janet Chacón, told the outlet.

And demonstrators held English-language signs proclaiming, "Yankees Go Home!" as well as banners reading, “Fuera los yanquis!" or "Out with the Yanks!"

Colombians were rallying after Petro called for a mass mobilization days after Trump ordered a military attack in Venezuela, including a bombing and the abduction of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. Maduro and Flores have pleaded not guilty to narco-terrorism charges in a court in New York City, while Trump and other White House officials have made clear in recent days that their objective in Venezuela is not to stop drug trafficking—a crime in which the country is not significantly involved—but to take control of its oil reserves.

Colombians marched together with Venezuelans in Cúcuta, with one man telling Reuters, "If they kidnap your president, they kidnap the entire homeland."

Protesters gathered at the Simon Bolivar Bridge in Cucuta, Colombia, to demonstrate against US President Donald Trump, responding to a call by Colombian President Gustavo Petro under the slogan 'Colombia is free and sovereign' pic.twitter.com/y5FIMweCbN

— Reuters (@Reuters) January 8, 2026

Soon after invading Venezuela, Trump and other officials including Secretary of State Marco Rubio suggested they could soon attack other Latin Amercian countries and try to overthrow their leaders.

Officials in Cuba's socialist government, said Rubio, are "in a lot of trouble," while Trump said the US is "going to have to do something" about drug cartels operating in Mexico.

Regarding Colombia, Trump cited no evidence as he accused the left-wing Petro of "making cocaine and selling it to the United States" and said an invasion of the country "sounds good to me." Petro has not been linked to the drug trade in Colombia.

Petro has vehemently condemned Trump's escalation in Latin America in recent months and has accused the president of murder in the Caribbean, where the US has bombed dozens of boats and killed more than 100 people since September, accusing them of drug trafficking without releasing any evidence.

After the Venezuela attack and the threats toward other countries in the region, Petro warned that Trump had awakened a "jaguar," referring to the opposition of the public in Colombia and across Latin American regarding US imperialism.

After calling on Colombians to take to the streets, Petro spoke to Trump on the phone at the US president's request and accepted an invitation to the White House. Trump said it was "a great honor" to speak with the Colombian leader.

Petro told protesters in Bogotá that the speech he had planned to give had been "quite harsh."

“For 34 years, peace has been my priority,” he said. “And I know that peace is found through dialogue. That is why I accept President Trump’s proposal to talk.”

"If there is no dialogue, there is war. The history of Colombia has taught us that," the president added.

But he also made clear to thousands of supporters, many of whom carried placards with pictures of Petro, that “what happened in Venezuela was, in my opinion, illegal."

"We cannot lower our guard," he said. “Words need to be followed by deeds."

In Cúcuta, a teacher named Marta Jiménez denounced a number of European leaders who have refused to clearly condemn Trump's invasion of Venezuela's neighbor, even as legal scholars have said it was a clear violation of the United Nations Charter.

“They are leaving him to fly, free as a bird over every single country, to do whatever he likes," she said, expressing concern that Trump's next target "might be Nicaragua, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru—any of them."

En Colombia, la sociedad salió masivamente en 12 ciudades, para rechazar la injerencia y las amenazas del presidente de EEUU. Se trató de una jornada con mensajes en favor de la unidad de los pueblos de Nuestra América y El Caribe. @teleSURtv @TobarteleSUR @petrogustavo pic.twitter.com/0RD4QvjHsu

— teleSUR Colombia (@teleSURColombia) January 8, 2026

Protests were also held this week in countries including Argentina and Brazil, with demonstrators expressing solidarity with the rest of Latin America in light of Trump's threats and attacks.

“The message from the people of Latin America is: ‘Donald Trump, get your hands off Latin America,'" Brazilian Congressman Reimont Otoni said at a rally outside the US consulate in Rio de Janeiro. "Latin America isn’t the [United States'] backyard."