August, 26 2013, 11:26am EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Sam Husseini, (202) 347-0020; or David Zupan, (541) 484-9167

"Divorcing 'Civil Rights' from Economic Justice": Myths of the March

BILL FLETCHER, billfletcherjr at gmail.com

Fletcher is a columnist for BlackCommentator.com and a senior scholar for the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. Fletcher is the co-author of Solidarity Divided: The Crisis in Organized Labor and A New Path Toward Social Justice.

He recently wrote the piece "Claiming and Teaching the 1963 March on Washington." Here's an excerpt:

WASHINGTON

BILL FLETCHER, billfletcherjr at gmail.com

Fletcher is a columnist for BlackCommentator.com and a senior scholar for the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C. Fletcher is the co-author of Solidarity Divided: The Crisis in Organized Labor and A New Path Toward Social Justice.

He recently wrote the piece "Claiming and Teaching the 1963 March on Washington." Here's an excerpt:

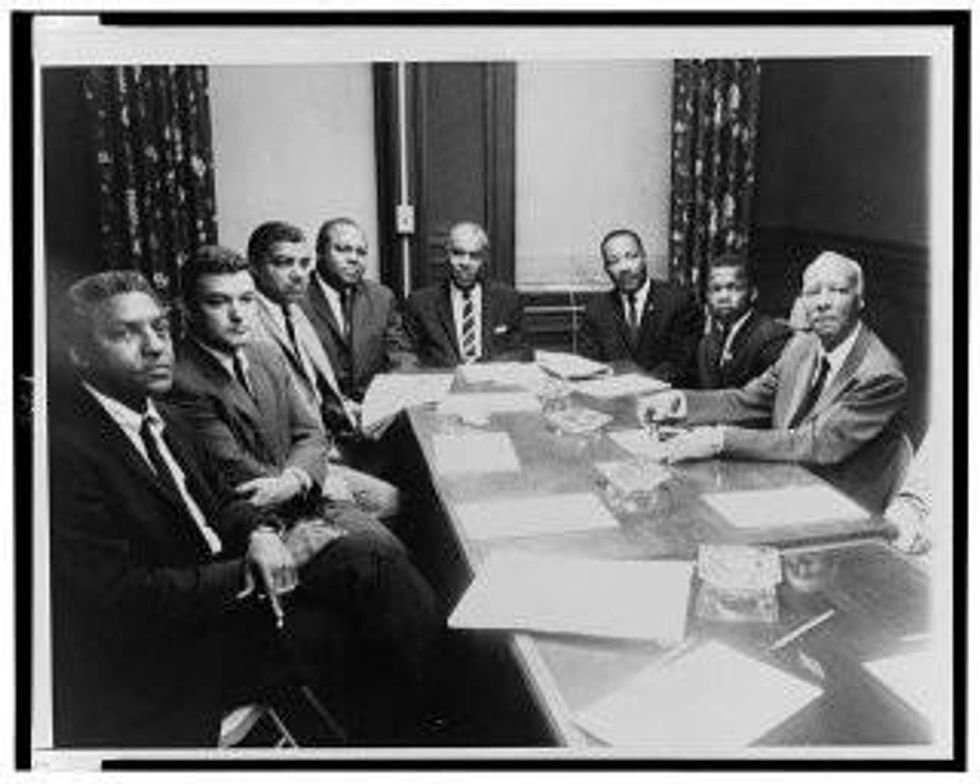

1. The context: The idea for the march in 1963 did not appear out of nowhere, and the fact that A. Philip Randolph originated it was no accident. The notion of the March on Washington in 1963 was, in certain respects, the revival of an idea from 1941 when Randolph convened a group to plan a march on Washington, D.C. to protest the segregation of the growing war industry. That march, which was planned as a black march on Washington, never happened because the mere threat of 100,000 African Americans marching forced President Franklin Roosevelt to give in to the demand for an executive order bringing about formal desegregation of the war industry.

3. The march's principal organizer was Bayard Rustin: This year President Obama will posthumously award Bayard Rustin the Medal of Freedom, however teaching about Rustin complicates the simplistic Civil Rights narrative offered to students by corporate history textbooks. Rustin was a gay pacifist with a long history of organizing, but despite his record of achievements, homophobia led to him being denied the title of national director of the march--technically, he served under Randolph.

Rustin closed the march with a list of demands and had everyone pledge "that I will not relax until victory is won." [Among the demands: "We demand that there be an increase in the national minimum wage so that men may live in dignity."] He was a complicated character who remained in organized labor and became a mentor to many, especially to younger activists in the burgeoning gay rights movement. At the same time, he refused to later condemn the Vietnam War and was critical of the Black Power Movement.

4. The march was controversial on many levels within the Black Freedom Movement: Individuals, such as Malcolm X, were critical of it, albeit in a contradictory manner, claiming that it would not amount to anything. And there were those within the march who, like then-SNCC chairman John Lewis, wanted a more militant posture.

5. The economic situation for African Americans was not addressed in any fundamental manner in the aftermath of the march: There were periodic improvements, but the crisis that Randolph and the NALC saw brewing in the early 1960s took on the features of a catastrophe by the mid to late 1970s, a fact that we have been living with ever since. Divorcing "civil rights" from economic justice is a feature common to mainstream approaches to history, including those found in school curricula.

6. The entirety of Dr. King's August 28, 1963 address should be read: What comes across is something very different from the morally righteous and tame "I Have a Dream!" clips and textbook soundbites usually offered around the time of Dr. King's birthday. In fact, the speech is a militant and audacious indictment of Jim Crow segregation and the situation facing African Americans.

To truly honor the legacy of this anniversary, teachers should have students compare the King of the actual speech with the King from the clips. It would also be useful to have students read and discuss some of the day's other speeches. For example, in Randolph's opening speech he proclaimed that those gathered before him represented "the advance guard of a massive moral revolution" aimed at creating a society where "the sanctity of private property takes second place to the sanctity of the human personality." This is a sentiment that we never hear about that day.

A nationwide consortium, the Institute for Public Accuracy (IPA) represents an unprecedented effort to bring other voices to the mass-media table often dominated by a few major think tanks. IPA works to broaden public discourse in mainstream media, while building communication with alternative media outlets and grassroots activists.

LATEST NEWS

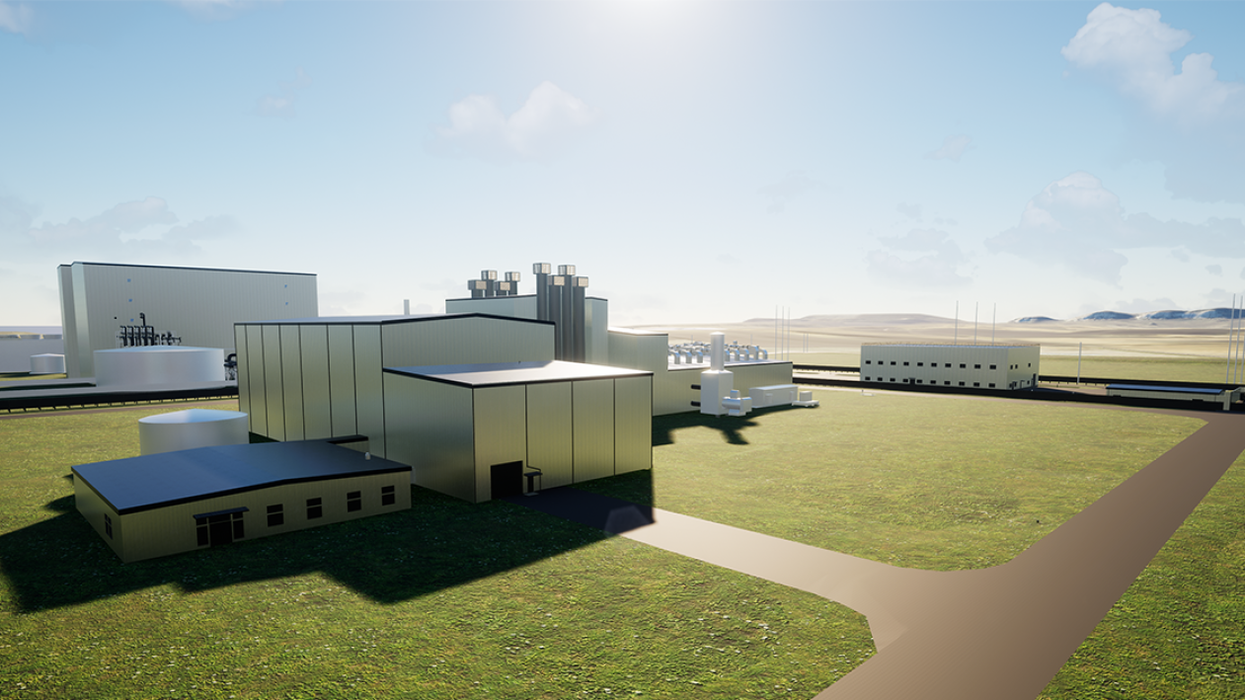

Trump Regulators Ripped for 'Rushed' Approval of Bill Gates' Nuclear Reactor in Wyoming

"Make no mistake, this type of reactor has major safety flaws compared to conventional nuclear reactors that comprise the operating fleet," said one expert.

Dec 03, 2025

A leading nuclear safety expert sounded the alarm Tuesday over the Trump administration's expedited safety review of an experimental nuclear reactor in Wyoming designed by a company co-founded by tech billionaire Bill Gates and derided as a "Cowboy Chernobyl."

On Monday, the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) announced that it has "completed its final safety evaluation" for Power Station Unit 1 of TerraPower's Natrium reactor in Kemmerer, Wyoming, adding that it found "no safety aspects that would preclude issuing the construction permit."

Co-founded by Microsoft's Gates, TerraPower received a 50-50 cost-share grant for up to $2 billion from the US Department of Energy’s Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program. The 345-megawatt sodium-cooled small modular reactor (SMR) relies upon so-called passive safety features that experts argue could potentially make nuclear accidents worse.

However, federal regulators "are loosening safety and security requirements for SMRs in ways which could cancel out any safety benefits from passive features," according to Union of Concerned Scientists nuclear power safety director Edwin Lyman.

"The only way they could pull this off is by sweeping difficult safety issues under the rug."

The reactor’s construction permit application—which was submitted in March 2024—was originally scheduled for August 2026 completion but was expedited amid political pressure from the Trump administration and Congress in order to comply with an 18-month timeline established in President Donald Trump’s Executive Order 14300.

“The NRC’s rush to complete the Kemmerer plant’s safety evaluation to meet the recklessly abbreviated schedule dictated by President Trump represents a complete abandonment of its obligation to protect public health, safety, and the environment from catastrophic nuclear power plant accidents or terrorist attacks," Lyman said in a statement Tuesday.

Lyman continued:

The only way the staff could finish its review on such a short timeline is by sweeping serious unresolved safety issues under the rug or deferring consideration of them until TerraPower applies for an operating license, at which point it may be too late to correct any problems. Make no mistake, this type of reactor has major safety flaws compared to conventional nuclear reactors that comprise the operating fleet. Its liquid sodium coolant can catch fire, and the reactor has inherent instabilities that could lead to a rapid and uncontrolled increase in power, causing damage to the reactor’s hot and highly radioactive nuclear fuel.

Of particular concern, NRC staff has assented to a design that lacks a physical containment structure to reduce the release of radioactive materials into the environment if a core melt occurs. TerraPower argues that the reactor has a so-called "functional" containment that eliminates the need for a real containment structure. But the NRC staff plainly states that it "did not come to a final determination of the adequacy and acceptability of functional containment performance due to the preliminary nature of the design and analysis."

"Even if the NRC determines later that the functional containment is inadequate, it would be utterly impractical to retrofit the design and build a physical containment after construction has begun," Lyman added. "The potential for rapid power excursions and the lack of a real containment make the Kemmerer plant a true ‘Cowboy Chernobyl.’”

The proposed reactor still faces additional hurdles before construction can begin, including a final environmental impact assessment. However, given the Trump administration's dramatic regulatory rollback, approval and construction are highly likely.

Former NRC officials have voiced alarm over the Trump administration's tightened control over the agency, which include compelling it to send proposed reactor safety rules to the White House for review and possible editing.

Allison Macfarlane, who was nominated to head the NRC during the Obama administration, said earlier this year that Trump's approach marks “the end of independence of the agency.”

“If you aren’t independent of political and industry influence, then you are at risk of an accident,” she warned.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Report Shows How Recycling Is Largely a 'Toxic Lie' Pushed by Plastics Industry

"These corporations and their partners continue to sell the public a comforting lie to hide the hard truth: that we simply have to stop producing so much plastic," said one campaigner.

Dec 03, 2025

A report published Wednesday by Greenpeace exposes the plastics industry as "merchants of myth" still peddling the false promise of recycling as a solution to the global pollution crisis, even as the vast bulk of commonly produced plastics remain unrecyclable.

"After decades of meager investments accompanied by misleading claims and a very well-funded industry public relations campaign aimed at persuading people that recycling can make plastic use sustainable, plastic recycling remains a failed enterprise that is economically and technically unviable and environmentally unjustifiable," the report begins.

"The latest US government data indicates that just 5% of US plastic waste is recycled annually, down from a high of 9.5% in 2014," the publication continues. "Meanwhile, the amount of single-use plastics produced every year continues to grow, driving the generation of ever greater amounts of plastic waste and pollution."

Among the report's findings:

- Only a fifth of the 8.8 million tons of the most commonly produced types of plastics—found in items like bottles, jugs, food containers, and caps—are actually recyclable;

- Major brands like Coca-Cola, Unilever, and Nestlé have been quietly retracting sustainability commitments while continuing to rely on single-use plastic packaging; and

- The US plastic industry is undermining meaningful plastic regulation by making false claims about the recyclability of their products to avoid bans and reduce public backlash.

"Recycling is a toxic lie pushed by the plastics industry that is now being propped up by a pro-plastic narrative emanating from the White House," Greenpeace USA oceans campaign director John Hocevar said in a statement. "These corporations and their partners continue to sell the public a comforting lie to hide the hard truth: that we simply have to stop producing so much plastic."

"Instead of investing in real solutions, they’ve poured billions into public relations campaigns that keep us hooked on single-use plastic while our communities, oceans, and bodies pay the price," he added.

Greenpeace is among the many climate and environmental groups supporting a global plastics treaty, an accord that remains elusive after six rounds of talks due to opposition from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and other nations that produce the petroleum products from which almost all plastics are made.

Honed from decades of funding and promoting dubious research aimed at casting doubts about the climate crisis caused by its products, the petrochemical industry has sent a small army of lobbyists to influence global treaty negotiations.

In addition to environmental and climate harms, plastics—whose chemicals often leach into the food and water people eat and drink—are linked to a wide range of health risks, including infertility, developmental issues, metabolic disorders, and certain cancers.

Plastics also break down into tiny particles found almost everywhere on Earth—including in human bodies—called microplastics, which cause ailments such as inflammation, immune dysfunction, and possibly cardiovascular disease and gut biome imbalance.

A study published earlier this year in the British medical journal The Lancet estimated that plastics are responsible for more than $1.5 trillion in health-related economic losses worldwide annually—impacts that disproportionately affect low-income and at-risk populations.

As Jo Banner, executive director of the Descendants Project—a Louisiana advocacy group dedicated to fighting environmental racism in frontline communities—said in response to the new Greenpeace report, "It’s the same story everywhere: poor, Black, Brown, and Indigenous communities turned into sacrifice zones so oil companies and big brands can keep making money."

"They call it development—but it’s exploitation, plain and simple," Banner added. "There’s nothing acceptable about poisoning our air, water, and food to sell more throwaway plastic. Our communities are not sacrifice zones, and we are not disposable people.”

Writing for Time this week, Judith Enck, a former regional administrator at the US Environmental Protection Agency and current president of the environmental justice group Beyond Plastics, said that "throwing your plastic bottles in the recycling bin may make you feel good about yourself, or ease your guilt about your climate impact. But recycling plastic will not address the plastic pollution crisis—and it is time we stop pretending as such."

"So what can we do?" Enck continued. "First, companies need to stop producing so much plastic and shift to reusable and refillable systems. If reducing packaging or using reusable packaging is not possible, companies should at least shift to paper, cardboard, glass, or metal."

"Companies are not going to do this on their own, which is why policymakers—the officials we elected to protect us—need to require them to do so," she added.

Although lawmakers in the 119th US Congress have introduced a handful of bills aimed at tackling plastic pollution, such proposals are all but sure to fail given Republican control of both the House of Representatives and Senate and the Trump administration's pro-petroleum policies.

Keep ReadingShow Less

Platner 20 Points Ahead of Mills in Maine Senate Race as Critics Spotlight Her Anti-Worker Veto Record

The new poll, said the progressive candidate, “lays clear what our theory is, which is that we are not going to defeat Susan Collins running the same exact kind of playbook that we’ve run in the past."

Dec 03, 2025

It's been more than a month since a media firestorm over old Reddit posts and a tattoo thrust US Senate candidate Graham Platner into the national spotlight, just as Maine Gov. Janet Mills was entering the Democratic primary race in hopes of challenging Republican Sen. Susan Collins—a controversy that did not appear at the time to make a dent in political newcomer Platner's chances in the election.

On Wednesday, the latest polling showed that the progressive combat veteran and oyster farmer has maintained the lead that was reported in a number of surveys just after the national media descended on the New England state to report on his past online comments and a tattoo that some said resembled a Nazi symbol, which he subsequently had covered up.

The Progressive Change Campaign Committee (PCCC), which endorsed Platner on Wednesday, commissioned the new poll, which showed him polling at 58% compared to Mills' 38%.

Nancy Zdunkewicz, a pollster with Z to A Polling, which conducted the survey on behalf of the PCCC, said the poll represented "really impressive early consolidation" for Platner, with the primary election still six months away.

“Platner isn’t just leading in the Democratic primary. He’s leading by a lot, 20 points—58% are supporting him,” Zdunkewicz told Zeteo. “Only 38% are supporting Mills. There are very few undecided voters or weak supporters for Mills to win over at this point in the race."

Platner has consistently spoken to packed rooms across Maine since launching his campaign in August, promoting a platform that is unapologetically focused on delivering affordability and a better quality of life for Mainers.

He supports expanding the popular Medicare program to all Americans; drew raucous applause at an early rally by declaring, “Our taxpayer dollars can build schools and hospitals in America, not bombs to destroy them in Gaza"; and has spoken in support of breaking up tech giants and a federal war crimes investigation into Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth over his deadly boat strikes in the Caribbean.

Mills entered the race after Democratic leaders including Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) urged her to. She garnered national attention earlier this year for standing up to President Donald Trump when he threatened federal funding for Maine over the state's policy of allowing students to play on school athletic teams that correspond with their gender.

But the PCCC survey found that when respondents learned details about each candidate, negative critiques of Mills were more damaging to her than Platner's old Reddit posts and tattoo.

Zdunkewicz disclosed Platner's recent controversy to the voters she surveyed, as well as his statements about how his views have shifted in recent years, and found that 21% of voters were more likely to back him after learning about his background. Thirty-nine percent said they were less likely to support him.

The pollster also talked to respondents about the fact that establishment Democrats pushed Mills, who is 77, to enter the race, and about a number of bills she has vetoed as governor, including a tax on the wealthy, a bill to set up a tracking system for rape kits, two bills to reduce prescription drug costs, and several bills promoting workers' rights.

Only 14% of Mainers said they were more likely to vote for Mills after learning those details, while 50% said they were less likely to support her.

At The Lever, Luke Goldstein on Wednesday reported that Mills' vetoes have left many with the "perception that she’s mostly concerned with business interests," as former Democratic Maine state lawmaker Andy O'Brien said. Corporate interests gave more than $200,000 to Mills' two gubernatorial campaigns.

Earlier this year, Mills struck down a labor-backed bill to allow farm workers to discuss their pay with one another without fear of retaliation. Last year, she blocked a bill to set a minimum wage for farm laborers, opposing a provision that would have allowed workers to sue their employers.

She also vetoed a bill banning noncompete agreements and one that would have banned anti-union tactics by corporations.

"In previous years," Goldstein reported, "she blocked efforts to stop employers from punishing employees who took state-guaranteed paid time off, killed a permitting reform bill to streamline offshore wind developments because it included a provision mandating union jobs, and vetoed a modest labor bill that would have required the state government to merely study the issue of paper mill workers being forced to work overtime without adequate compensation."

Speaking to PCCC supporters on Wednesday, Platner suggested the new polling shows that many Mainers agree with the central argument of his campaign: "We need to build power again for working people, both in Maine and nationally.”

The survey, he said, “lays clear what our theory is, which is that we are not going to defeat Susan Collins running the same exact kind of playbook that we’ve run in the past—which is an establishment politician supported by the power structures, supported by Washington, DC, coming up to Maine and trying to run a kind of standard race... We are really trying to build a grassroots movement up here."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular