SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"The Court’s decision today... against ICE’s unlawful effort to obstruct congressional oversight is a victory for the American people," said Rep. Joe Neguse.

Doubling down on a ruling from late last year, a federal judge on Monday once again rejected an effort by the Trump administration to block congressional lawmakers from accessing federal immigration detention facilities.

In the ruling, US District Judge Jia Cobb granted a temporary restraining order sought by Democratic members of the House of Representatives to overturn the US Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) policy of requiring lawmakers to give a week's notice before being granted access to US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention facilities.

Cobb had already overturned this DHS policy in a December ruling, arguing that it "was likely contrary to the terms of a limitations rider attached to" the department's annual appropriated funds.

However, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem in January reimplemented the one-week notice policy and argued that it was now being implemented with separate funds provided to DHS through the 2025 One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which did not contain the language used in the earlier limitations rider.

Cobb rejected this argument and found that "at least some of these resources that either have been or will be used to promulgate and enforce the notice policy have already been funded and paid for with... restricted annual appropriations funds," including "contracts or agreements that predate" the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

According to legal journalist Chris Geidner, the effect of Cobb's ruling will be that congressional oversight visits to ICE facilities will now be "allowed on request."

Rep. Joe Neguse (D-Colo.), the lead plaintiff in the case, hailed Cobb's ruling and vowed to keep putting pressure on the Trump administration to comply with the law.

"The Court’s decision today to grant a temporary restraining order against ICE’s unlawful effort to obstruct congressional oversight is a victory for the American people," said Neguse. "We will keep fighting to ensure the rule of law prevails."

One doctor warned that the outbreak "will become an epidemic if we don't act immediately."

Public health experts and immigrant advocates sounded the alarm Sunday over a measles outbreak at a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement internment center in Texas where roughly 1,200 people, including over 400 children, are being held.

Texas officials confirmed Saturday that two detainees at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center, located about 75 miles (120 km) southwest of San Antonio, are infected with measles.

"Medical staff is continuing to monitor the detainees' conditions and will take appropriate and active steps to prevent further infection," the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said in a statement. "All detainees are being provided with proper medical care."

DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin said Sunday that ICE "immediately took steps to quarantine and control further spread and infection, ceasing all movement within the facility and quarantining all individuals suspected of making contact with the infected."

Responding to the development, Dr. Lee Rogers of UT Health San Antonio wrote in a letter to Texas state health officials that the Dilley outbreak "will become an epidemic if we don't act immediately" by establishing "a single public health incident command center."

"Viruses are not political," Rogers stressed. "They do not care about one's immigration status. Measles will spread if we allow uncertainty and delay to substitute for reasoned public health action."

Dr. Benjamin Mateus took aim at the Trump administration's wider policy of "criminalizing immigrant families and confining children in camps," which he called a form of "colonial policy" from which disease is the "predictable outcome."

Measles is a highly contagious viral disease that can kill or cause serious complications, particularly among unvaccinated people. The United States declared measles eliminated in 2000, but declining vaccination fueled by misinformation has driven a resurgence in the disease, and public health experts warn that the US is close to following Canada, which lost its elimination status late last year.

Many experts blame this deadly and preventable setback on the vaccine-averse policies and practices of the Trump administration, particularly at the Department of Health and Human Services, led by vaccine conspiracy theorist Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

US measles cases this year already exceed the total for the whole of 2023 and 2024 combined, and it is only January. Yikes.

[image or embed]

— Dr. Lucky Tran (@luckytran.com) January 29, 2026 at 12:29 PM

Critics also slammed ICE's recent halt on payments to third-party providers of detainee healthcare services.

Immigrant advocates had previously warned of a potential measles outbreak at the Dilley lockup. Neha Desai, an attorney at the Oakland, California-based National Center of Youth Law, told CBS News that authorities could use the outbreak as a pretext for preventing lawyers and lawmakers from inspecting the facility.

"We are deeply concerned for the physical and the mental health of every family detained at Dilley," Desai said. "It is important to remember that no family needs to be detained—this is a choice that the administration is making."

Run by ICE and private prison profiteer CoreCivic, the Dilley Immigration Processing Center has been plagued by reports of poor health and hygiene conditions. The facility is accused of providing inadequate medical care for children.

Detainees—who include people legally seeking asylum in the US—report prison-like conditions and say they've been served moldy food infested with worms and forced to drink putrid water. Some have described the facility as "truly a living hell."

The internment center has made headlines not only for its harsh conditions, but also for its high-profile detainees, including Liam Conejo Ramos, a 5-year-old abducted by ICE agents in Minneapolis last month and held along with his father at the facility before a judge ordered their release last week. The child's health deteriorated while he was at Dilley.

On Sunday, the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC)—the nation's oldest Latino civil rights organization—held a protest outside the Dilley lockup, demanding its closure.

"Migrant detention centers in America are a moral failure,” LULAC national president Roman Palomares said in a statement. "When a nation that calls itself a beacon of freedom detains children behind razor wire, separates families from their communities, and holds them in isolated conditions, we have crossed a dangerous line."

In the name of “defend[ing] your homeland” and “defend[ing] your culture,” his administration will arrest, detain, cage, traumatize, tear-gas, use children as bait, deny people their rights, deport, murder US citizens, and terrorize communities across the nation.

Not finished terrorizing Minnesota, the Trump administration is seeking to open a new front in their war against America. This time, the battlefield will be Ohio, and Haitians will be the scapegoat.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced it would end Temporary Protection Status (TPS) for Haitians, with an effective termination date of February 3, 2026. According to a federal notice issued by DHS in November 2025, “Based on the Department's review, the Secretary [Kristi Noem] has determined that while the current situation in Haiti is concerning, the United States must prioritize its national interests and permitting Haitian nationals to remain temporarily in the United States is contrary to the US national interest.”

Per this federal notice, “there are Haitian nationals who are Temporary Protected Status recipients who have been the subject of administrative investigations for fraud, public safety, and national security.” No specifics are offered with regards the scope of this problem, or even the number of Haitians on TPS who have been charged or convicted of any crimes. Instead, they offer a few specific examples. This includes people like Wisteguens Jean Quely Charles, who importantly was not a TPS recipient.

Nevertheless, DHS argues that Charles’s “case underscores the broader risk posed by rising Haitian migration,” especially in the context of a “high-volume border environment” with poor vetting. They allege that the “inability of the previous [Biden] administration to reliably screen aliens from a country with limited law enforcement infrastructure and widespread gang activity presents a clear and growing threat to US public safety.”

The actions we take today will determine whether America embraces multiculturalism or becomes an ethnostate that treats diversity like a plague to be eradicated.

In short, DHS offers no concrete evidence that Haitians on TPS pose an actual threat to public safety or national security—only that they might pose a threat because their potential for being a threat was not properly assessed. Moreover, this potential cannot be properly assessed now because Haiti’s “lack of functional government authority” makes it too difficult to access “critical information” (e.g., criminal histories).

As per usual with the Trump administration, fearmongering replaces facts. In 2021, President Donald Trump claimed that all Haitians have AIDS—this is false (obviously). In 2024, he claimed that, “In Springfield, [Haitians] are eating the dogs. The people that came in, they are eating the cats. They’re eating—they are eating the pets of the people that live there.” There were no credible reports of this occurring.

Trump describes immigrants as dangerous criminals. Yet, studies have repeatedly shown that immigrants—including undocumented immigrants—commit far fewer crimes than US citizens. Haitian immigrants are no exceptions. Undocumented Haitian immigrants, for instance, have an incarceration rate that is 81% below US-born Americans.

The situation in Ohio is also no different. In Springfield, home to one of the state’s largest Haitian communities, “Haitians are more likely to be the victims of crime than they are to be the perpetrators in our community. Clark County jail data shows there are 199 inmates in our county jail this week. Two of them are Haitian. That’s 1% (as of Sept. 8).” The thousands of Haitians with TPS protection living in Ohio have made themselves indispensable to the state. As Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, remarks, “If you took Haitians away overnight, I will tell you that the business people there will tell you that’s going to be a big problem for the economy of the community.” In Springfield alone, Haitian immigrants have contributed to higher wage growth while reversing the city’s population decline.

Despite this, DHS will deliberately send Haitians back to a country that they themselves describe as being currently unsafe. So, the question is: why? The answer is because they are Black and foreign. This is also why his administration is so aggressively targeting Somalis.

For Trump, both Somalia and Haiti are “shithole countries”—“places that are a disaster, right? Filthy, dirty, disgusting, ridden with crime.” At the 2026 Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum, Trump ranted: “The situation in Minnesota reminds us that the West cannot mass import foreign cultures, which have failed to ever build a successful society of their own. I mean, we’re taking people from Somalia, and Somalia is a failed—it’s not a nation.”

In Trump’s view, Somalia and Haiti are dirty and crime ridden because their people are dirty and prone to crime. Places and people are inextricably tied to him—bad people will always produce bad places; bad places are always the byproduct of bad people. If the US is failing, it’s because we have “imported” too many bad people. This is why, for Trump, almost every social problem from housing affordability to low wages to employment to high crime rates can be solved by mass deportations. From healthcare to election integrity, immigrants are the problem for his administration.

This sentiment is explicitly expressed by US Homeland Security Adviser Stephen Miller. He remarks, “This is the great lie of mass migration. You are not just importing individuals. You are importing societies. No magic transformation occurs when failed states cross borders. At scale, migrants and their descendants recreate the conditions, and terrors, of their broken homelands.” Mass migration for Miller is a cross-generational problem. In his view, if Somalis come to America, then they and their children will cause America to fail just like they caused Somalia to fail. For Miller and Trump, this is a problem of cultural and biological determinism. It is a problem of “bad genes” that determine behaviors like criminality, as well as “toxic” ideologies like diversity, equity, and inclusion and ‘hateful’ beliefs like Islam that impede American progress.

When Trump remarks that “illegal immigration is poisoning the blood of our country,” the poison in question is the people themselves and the threat their mere presence represents. Put another way, for Trump, all immigrants from poor countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America are akin to tumors in the body politic. Whether they are malignant or benign makes little difference, the safest and most effective response is to surgically remove (deport) them. Even if it turns out that those growths are helping the body politic, they are still foreign agents that should not be present. They are not part of the “very special culture” that built the West—“the precious inheritance that America and Europe have in common.” An inheritance that must be protected from “unchecked mass migration" and “endless foreign imports.” Whether it’s MAGA’s racism or MAHA’s anti-vaxxerism, the Trump administration will reject anything it arbitrarily deems a foreign toxin.

While the Trump administration has deployed federal agents across the nation, we should not be surprised that the “largest immigrant operation ever” has targeted Somalis, a community of predominantly Black, Muslim, and immigrant people. Whiteness and Blackness have always been direct polar opposites within the Western racial imaginary—the former signifying all that is good, the latter all that is bad. For Trump, it is whiteness that “abolished slavery; secured civil rights; defeated communism and fascism; and built the most fair, equal, and prosperous nation in human history.” Of course, none of this is true: Haiti was the first nation to end slavery, Black and other people of color fought for civil rights, and the Trump administration is a fascist regime.

None of these facts will stop the Trump administration’s crusade against “foreign invaders” spawned from “hellholes” who threaten “civilization erasure.” In the name of “defend[ing] your homeland” and “defend[ing] your culture,” his administration will arrest, detain, cage, traumatize, tear-gas, use children as bait, deny people their rights, deport, murder US citizens, and terrorize communities across the nation. No cost is too high in this Holy War to save the proverbial soul of America.

We are at a critical juncture. The actions we take today will determine whether America embraces multiculturalism or becomes an ethnostate that treats diversity like a plague to be eradicated. We must continue to protest nationwide against Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Trump administration. We must continue to monitor and observe ICE’s tactics. We must push elected officials to fulfill their obligation to the people and use their authority to keep Trump in check. At a time when the Trump administration wants nothing more than to divide us, we must come together and resist.

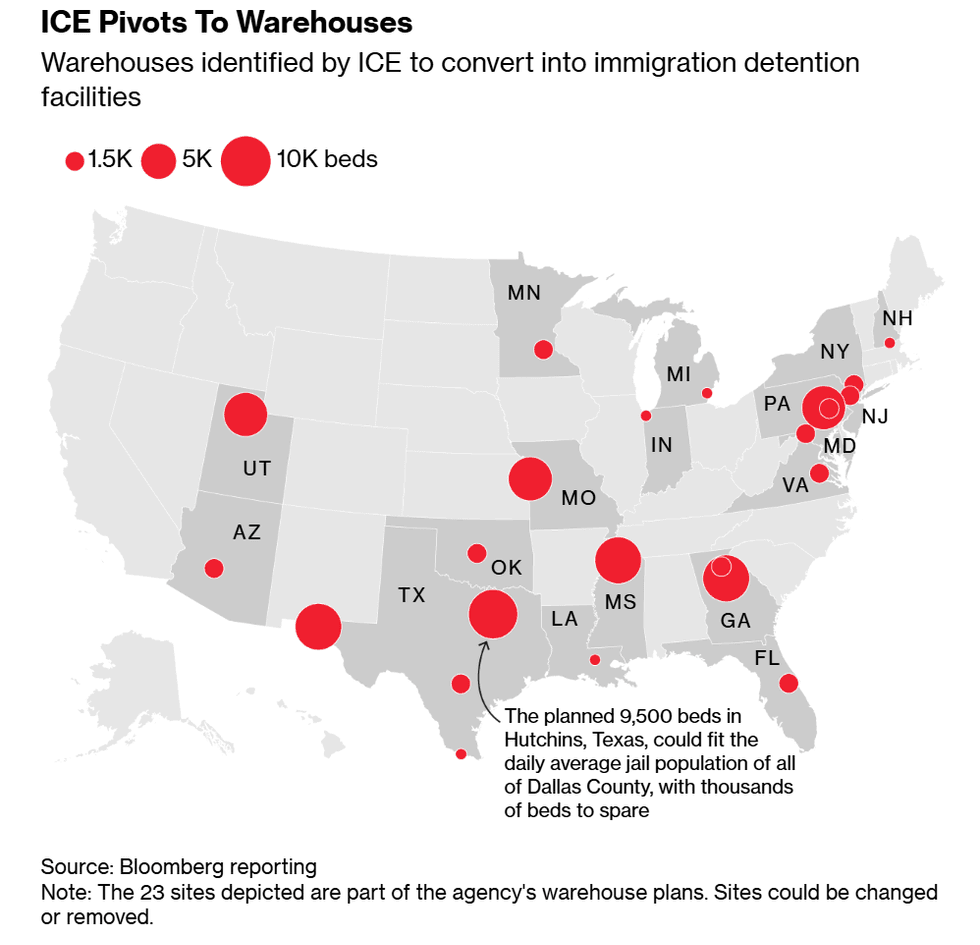

The Department of Homeland Security is using a repurposed $55 billion Navy contract to convert warehouses into makeshift jails and plan sprawling tent cities in remote areas.

In the wake of immigration agents' killings of three US citizens within a matter of weeks, the Department of Homeland Security is quietly moving forward with a plan to expand its capacity for mass detention by using a military contract to create what Pablo Manríquez, the author of the immigration news site Migrant Insider calls "a nationwide 'ghost network' of concentration camps."

On Sunday, Manríquez reported that "a massive Navy contract vehicle, once valued at $10 billion, has ballooned to a staggering $55 billion ceiling to expedite President Donald Trump’s 'mass deportation' agenda."

It is the expansion of a contract first reported on in October by CNN, which found that DHS was "funneling $10 billion through the Navy to help facilitate the construction of a sprawling network of migrant detention centers across the US in an arrangement aimed at getting the centers built faster, according to sources and federal contracting documents."

The report describes the money as being allocated for "new detention centers," which "are likely to be primarily soft-sided tents and may or may not be built on existing Navy installations, according to the sources familiar with the initiative. DHS has often leaned on soft-sided facilities to manage influxes of migrants."

According to a source familiar with the project, "the goal is for the facilities to house as many as 10,000 people each, and are expected to be built in Louisiana, Georgia, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Utah, and Kansas."

Now Manríquez reports that the project has just gotten much bigger after a Navy grant was repurposed weeks ago. It was authorized through the Worldwide Expeditionary Multiple Award Contract (WEXMAC), a flexible purchasing system that the government uses to quickly move military equipment to dangerous and remote parts of the world.

The contract states that the money is being repurposed for "TITUS," an abbreviation for "Territorial Integrity of the United States." While it's not unusual for Navy contracts to be used for expenditures aimed at protecting the nation, Manríquez warned that such a staggering movement of funds for domestic detention points to something ominous.

“This $45 billion increase, published just weeks ago, converts the US into a ‘geographic region’ for expeditionary military-style detention,” he wrote. "It signals a massive, long-term escalation in the government’s capacity to pay for detention and deportation logistics. In the world of federal contracting, it is the difference between a temporary surge and a permanent infrastructure."

He says the use of the military funding mechanism is meant to disburse funds quickly, without the typical bidding war among contractors, which would typically create a period of public scrutiny. Using the Navy contract means that new projects can be created with “task orders,” which can be turned around almost immediately, when “specific dates and locations are identified” by DHS.

"It means the infrastructure is currently a 'ghost' network that can be materialized anywhere in the US the moment a site is picked," Manríquez wrote.

Amid its push to deport 1 million people each year, the White House has said it needs to dramatically increase the scale of its detention apparatus to add more beds for those who are arrested. But Manríquez said documents suggest "this isn't just about bed space; it’s about the rapid deployment of self-contained cities."

In addition to tent cities capable of housing thousands, contract line items include facilities meant for sustained living—including closed tents likely for medical treatment and industrial-sized grills for food preparation.

They also include expenditures on "Force Protection" equipment, like earth-filled defensive barriers, 8-foot-high CONEX box walls, and “Weather Resistant” guard shacks.

Eric Feigl-Ding, an epidemiologist and health economist, said the contract's provision of materials meant to deal with medical needs and death was "extra chilling." According to the report, "services extend to 'Medical Waste Management,' with specific protocols for biohazard incinerators."

The new reporting from Migrant Insider comes on the heels of a report last week from Bloomberg that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has used some of the $45 billion to purchase warehouses in nearly two dozen remote communities, each meant to house thousands of detainees, which it said "could be the largest expansion of such detention capacity in US history."

The plans have been met with backlash from locals, even in the largely Republican-leaning areas where they are being constructed:

This month, demonstrators protested warehouse conversions in New Hampshire, Utah, Texas and Georgia after the Washington Post published an earlier version of the conversion plan.

In mid-January, a planned tour for contractors of a potential warehouse site in San Antonio was canceled after protesters showed up the same day, according to a person familiar with the scheduled visit.

In Salt Lake City, the Ritchie Group, a local family business that owns the warehouse ICE identified as a future “mega center” jail, said it had “no plans to sell or lease the property in question to the federal government” after protesters showed up at their offices to pressure them.

On January 20, Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) joined hundreds of protesters outside a warehouse in Hagerstown, Maryland, that was set to be converted into a facility that will hold 1,500 people.

The senator called the construction of it and other detention facilities "one of the most obscene, one of the most inhumane, one of the most illegal operations being carried out by this Trump administration."

Reports of a new influx of funding from the Navy come as Democrats in Congress face pressure to block tens of billions in new funding for DHS and ICE during budget negotiations.

"If Congress does nothing, DHS will continue to thrive," Manríquez said. "With three more years pre-funded, plus a US Navy as a benefactor, Secretary Kristi Noem—or any potential successor—has the legal and financial runway to keep the business of creating ICE concentration camps overnight in American communities running long after any news cycle fades."