SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

If the Trump administration’s assaults on Venezuela and threats to Colombia and Mexico have a familiar stench, they should. For more than two centuries the United States government has acted as if it owned the Western Hemisphere, with the right of conquest, intervention, and interference part of the natural order.

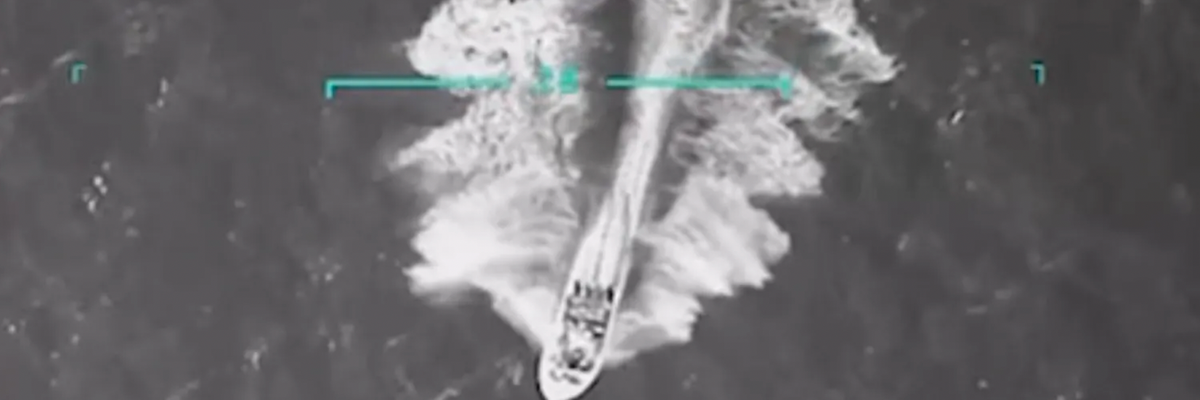

As of this writing, at least 66 people—Venezuelans, Colombians, and possibly some of other nationalities—have been extrajudicially murdered by President Donald Trump and the US military in 17 separate reported attacks. Numerous naval ships and aircraft are deployed in the southern Caribbean, including the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier, which has nearly twice the number of fighter planes as the entire Venezuelan Air Force.

All that hardware is hardly needed for the flimsy cover story of intercepting fentanyl which is not manufactured in, or transported from, Venezuela. Trump has publicly confirmed there are covert CIA operations in Venezuela.

In Caracas, there have been reports of “false flag” attacks by CIA operatives on a US warship and on the US embassy, likely intended to draw Venezuela into military confrontation. “To much of the world, it all looks like a push for regime change in Venezuela,” assessed Emily Goodin and Claire Heddles in the Miami Herald, despite recent Trump contradictions.

Military aggression, covert action, and dreams of regime change in the hemisphere are the “oldest moves in the American foreign policy playbook,” wrote columnist Gustavo Arellano in the Los Angeles Times. “For more than two centuries, the United States has treated Latin America as its personal piñata, bashing it silly for goods and not caring about the ugly aftermath.”

The story dates back to the US founders, details historian Greg Gambrill in America, América, his new survey of hemispheric relations. “It is impossible not to look forward to distant times” when the US will “cover the whole Northern, if not Southern, continent with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms,” Thomas Jefferson wrote.

President James Monroe codified that goal in 1823 in what became the Monroe Doctrine, explained Arellano. “It is known to all that we derive [our blessings] from the excellence of our institutions. Ought we not, then, to adopt every measure which may be necessary to perpetuate them?” Monroe asked.

That doctrine “sanctioned the idea that the United States has a right to project its powers beyond its official borders,” explains Gambrill. The US cited it repeatedly “as a self-issued warrant to intervene against its southern neighbors, from the taking of Texas to more recent efforts at regime change in Venezuela and Nicaragua.” In 1823, the Supreme Court gave its blessing, declaring “conquest gives a title to which the Courts of the conqueror cannot deny.”

Sovereign nations hammered by the US, many of them repeatedly, include Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Mexico was the first target and it remains one to this day. Trump has begun detailed planning to attack drug cartels in Mexico with ground operations, NBC News reported this week. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, whose politics and gender fit the profile of leaders Trump disdains, is unlikely to welcome it. When talk of Trump bombing cartels inside Mexico surfaced this Spring, Sheinbaum said, “we reject any form of intervention or interference.”

Within a few years of the Monroe Doctrine’s enactment, pro-slavery US leaders were encouraging slaveholders to flood northern Mexico, orchestrating a rebellion to form an “independent country” of Texas that was soon absorbed as a US slave state.

President James Polk expanded that acquisition, invading Mexico in 1846, occupying Mexico City, and forcing a massive land grab of up to one-third of Mexican territory, which would become much of the US Southwest. Abraham Lincoln, then in Congress, vehemently opposed the war in speeches and resolutions. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the war, later reflected, “to this day (I) regard the war as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

For decades after, US expansionists schemed to seize other territory in the hemisphere, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Their aspirations came to fruition with the 1898 war against Spain that resulted in a new overseas US empire that included Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam.

In the 20th Century, the interventions and abuses accelerated. President Theodore Roosevelt—backed with J.P. Morgan’s wealth—broke Panama off from Colombia so the US could build and own a canal. Most locals were unaware of their “independence” until “an American officer raised (Panama’s) ‘new flag’,” Grandin notes. Around the same time in Venezuela, a US corporate financier and speculator engineered control of a new asphalt industry, with the help of White House battleships, to feed a road-building boom in the US–shades of future US maneuvers to secure control of resources, including Venezuelan oil, the world’s largest oil reserves.

“Rubber, ivory, and palm-oil; tea, coffee, and cocoa; bananas, oranges, and other fruit; cotton, gold, and copper–they, and a hundred other things which dark and sweating bodies hand up to the white world from pits of slime, pay and pay well,” was how W.E.B. DuBois, described colonialism and racial capitalism, in a 1916 essay, “The Souls of White Folk.”

In 1910, Mexican insurgents overthrew longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz, beginning a tumultuous decade. The new leader, Francisco Madero, was assassinated, with covert US assistance. Meanwhile, US investors, who owned nearly half of all Mexican property value, encouraged US intervention. Newly-elected President Woodrow Wilson, who had campaigned on a peace platform, soon dispatched Marines and sailors to occupy Veracruz, although Wilson subsequently said the US had “no right to intervene in Mexico.”

It wasn't until 1933, under President Franklin Roosevelt, that the US largely paused “the doctrine of conquest and began to abide by the rule of law,” said Grandin in a Nation podcast describing what became known as the “Good Neighbor” policy. “Our Era of Imperialism Nears Its End,” proclaimed the New York Times. Not for long.

By the end of World War II, with an anti-Communist crusade in full force, leftists and social democratic reformers in Latin America became as endangered as those blacklisted and imprisoned at home. Concurrently, US trade policies promoted policies of underdevelopment, resource exploitation, and massive debt.

The CIA campaign to destabilize and overthrow a democratically elected government in Guatemala became a prelude for similar assaults in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs in 1961, Brazil in 1964, the Dominican Republic in 1965, and Chile in 1973. “Washington had a hand in 16 regime changes between 1961 and 1969,” notes Grandin.

It continued, notably with President Ronald Reagan’s offensives in Central America in the 1980s. When the International Court of Justice ruled his contra war in Nicaragua was illegal, Reagan simply withdrew from the ICJ, a flaunting of the post-World War II international law order that US administrations have followed ever since.

In his Nation podcast, Grandin depicts the latest US strikes as “obviously part of Trump's drive to use violence and force and establish dominance in whatever way he can muster” with Venezuela “the entry point to a reverse domino effect” for regime change against left and progressive-leaning governments in the region.

Grandin contrasts US behavior with two centuries of efforts by Latin American and Caribbean liberal leaders in repeated hemispheric conferences to build a very different democratic, non-interventionist model, beginning with a 1826 Panama Congress led by South American independence pioneer Simón Bolívar.

Cuban revolutionary José Martí was a key figure in the First International Conference of American States in 1889-1890. Delegates, other than the US, pushed for consensus opposing wars of aggression and territorial annexation, notes Grandin, around “a general principle that no powerful nation had the right to intervene in any way in the politics of other nations.”

According to Grandin, the lesson from Latin America has been “democracy in Latin America means social democracy. The world's first social democratic constitution was in Mexico. When Latin Americans are asked to define democracy, they talk about healthcare, they talk about education.” And a respect for national sovereignty.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

If the Trump administration’s assaults on Venezuela and threats to Colombia and Mexico have a familiar stench, they should. For more than two centuries the United States government has acted as if it owned the Western Hemisphere, with the right of conquest, intervention, and interference part of the natural order.

As of this writing, at least 66 people—Venezuelans, Colombians, and possibly some of other nationalities—have been extrajudicially murdered by President Donald Trump and the US military in 17 separate reported attacks. Numerous naval ships and aircraft are deployed in the southern Caribbean, including the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier, which has nearly twice the number of fighter planes as the entire Venezuelan Air Force.

All that hardware is hardly needed for the flimsy cover story of intercepting fentanyl which is not manufactured in, or transported from, Venezuela. Trump has publicly confirmed there are covert CIA operations in Venezuela.

In Caracas, there have been reports of “false flag” attacks by CIA operatives on a US warship and on the US embassy, likely intended to draw Venezuela into military confrontation. “To much of the world, it all looks like a push for regime change in Venezuela,” assessed Emily Goodin and Claire Heddles in the Miami Herald, despite recent Trump contradictions.

Military aggression, covert action, and dreams of regime change in the hemisphere are the “oldest moves in the American foreign policy playbook,” wrote columnist Gustavo Arellano in the Los Angeles Times. “For more than two centuries, the United States has treated Latin America as its personal piñata, bashing it silly for goods and not caring about the ugly aftermath.”

The story dates back to the US founders, details historian Greg Gambrill in America, América, his new survey of hemispheric relations. “It is impossible not to look forward to distant times” when the US will “cover the whole Northern, if not Southern, continent with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms,” Thomas Jefferson wrote.

President James Monroe codified that goal in 1823 in what became the Monroe Doctrine, explained Arellano. “It is known to all that we derive [our blessings] from the excellence of our institutions. Ought we not, then, to adopt every measure which may be necessary to perpetuate them?” Monroe asked.

That doctrine “sanctioned the idea that the United States has a right to project its powers beyond its official borders,” explains Gambrill. The US cited it repeatedly “as a self-issued warrant to intervene against its southern neighbors, from the taking of Texas to more recent efforts at regime change in Venezuela and Nicaragua.” In 1823, the Supreme Court gave its blessing, declaring “conquest gives a title to which the Courts of the conqueror cannot deny.”

Sovereign nations hammered by the US, many of them repeatedly, include Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Mexico was the first target and it remains one to this day. Trump has begun detailed planning to attack drug cartels in Mexico with ground operations, NBC News reported this week. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, whose politics and gender fit the profile of leaders Trump disdains, is unlikely to welcome it. When talk of Trump bombing cartels inside Mexico surfaced this Spring, Sheinbaum said, “we reject any form of intervention or interference.”

Within a few years of the Monroe Doctrine’s enactment, pro-slavery US leaders were encouraging slaveholders to flood northern Mexico, orchestrating a rebellion to form an “independent country” of Texas that was soon absorbed as a US slave state.

President James Polk expanded that acquisition, invading Mexico in 1846, occupying Mexico City, and forcing a massive land grab of up to one-third of Mexican territory, which would become much of the US Southwest. Abraham Lincoln, then in Congress, vehemently opposed the war in speeches and resolutions. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the war, later reflected, “to this day (I) regard the war as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

For decades after, US expansionists schemed to seize other territory in the hemisphere, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Their aspirations came to fruition with the 1898 war against Spain that resulted in a new overseas US empire that included Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam.

In the 20th Century, the interventions and abuses accelerated. President Theodore Roosevelt—backed with J.P. Morgan’s wealth—broke Panama off from Colombia so the US could build and own a canal. Most locals were unaware of their “independence” until “an American officer raised (Panama’s) ‘new flag’,” Grandin notes. Around the same time in Venezuela, a US corporate financier and speculator engineered control of a new asphalt industry, with the help of White House battleships, to feed a road-building boom in the US–shades of future US maneuvers to secure control of resources, including Venezuelan oil, the world’s largest oil reserves.

“Rubber, ivory, and palm-oil; tea, coffee, and cocoa; bananas, oranges, and other fruit; cotton, gold, and copper–they, and a hundred other things which dark and sweating bodies hand up to the white world from pits of slime, pay and pay well,” was how W.E.B. DuBois, described colonialism and racial capitalism, in a 1916 essay, “The Souls of White Folk.”

In 1910, Mexican insurgents overthrew longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz, beginning a tumultuous decade. The new leader, Francisco Madero, was assassinated, with covert US assistance. Meanwhile, US investors, who owned nearly half of all Mexican property value, encouraged US intervention. Newly-elected President Woodrow Wilson, who had campaigned on a peace platform, soon dispatched Marines and sailors to occupy Veracruz, although Wilson subsequently said the US had “no right to intervene in Mexico.”

It wasn't until 1933, under President Franklin Roosevelt, that the US largely paused “the doctrine of conquest and began to abide by the rule of law,” said Grandin in a Nation podcast describing what became known as the “Good Neighbor” policy. “Our Era of Imperialism Nears Its End,” proclaimed the New York Times. Not for long.

By the end of World War II, with an anti-Communist crusade in full force, leftists and social democratic reformers in Latin America became as endangered as those blacklisted and imprisoned at home. Concurrently, US trade policies promoted policies of underdevelopment, resource exploitation, and massive debt.

The CIA campaign to destabilize and overthrow a democratically elected government in Guatemala became a prelude for similar assaults in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs in 1961, Brazil in 1964, the Dominican Republic in 1965, and Chile in 1973. “Washington had a hand in 16 regime changes between 1961 and 1969,” notes Grandin.

It continued, notably with President Ronald Reagan’s offensives in Central America in the 1980s. When the International Court of Justice ruled his contra war in Nicaragua was illegal, Reagan simply withdrew from the ICJ, a flaunting of the post-World War II international law order that US administrations have followed ever since.

In his Nation podcast, Grandin depicts the latest US strikes as “obviously part of Trump's drive to use violence and force and establish dominance in whatever way he can muster” with Venezuela “the entry point to a reverse domino effect” for regime change against left and progressive-leaning governments in the region.

Grandin contrasts US behavior with two centuries of efforts by Latin American and Caribbean liberal leaders in repeated hemispheric conferences to build a very different democratic, non-interventionist model, beginning with a 1826 Panama Congress led by South American independence pioneer Simón Bolívar.

Cuban revolutionary José Martí was a key figure in the First International Conference of American States in 1889-1890. Delegates, other than the US, pushed for consensus opposing wars of aggression and territorial annexation, notes Grandin, around “a general principle that no powerful nation had the right to intervene in any way in the politics of other nations.”

According to Grandin, the lesson from Latin America has been “democracy in Latin America means social democracy. The world's first social democratic constitution was in Mexico. When Latin Americans are asked to define democracy, they talk about healthcare, they talk about education.” And a respect for national sovereignty.

If the Trump administration’s assaults on Venezuela and threats to Colombia and Mexico have a familiar stench, they should. For more than two centuries the United States government has acted as if it owned the Western Hemisphere, with the right of conquest, intervention, and interference part of the natural order.

As of this writing, at least 66 people—Venezuelans, Colombians, and possibly some of other nationalities—have been extrajudicially murdered by President Donald Trump and the US military in 17 separate reported attacks. Numerous naval ships and aircraft are deployed in the southern Caribbean, including the USS Gerald R. Ford aircraft carrier, which has nearly twice the number of fighter planes as the entire Venezuelan Air Force.

All that hardware is hardly needed for the flimsy cover story of intercepting fentanyl which is not manufactured in, or transported from, Venezuela. Trump has publicly confirmed there are covert CIA operations in Venezuela.

In Caracas, there have been reports of “false flag” attacks by CIA operatives on a US warship and on the US embassy, likely intended to draw Venezuela into military confrontation. “To much of the world, it all looks like a push for regime change in Venezuela,” assessed Emily Goodin and Claire Heddles in the Miami Herald, despite recent Trump contradictions.

Military aggression, covert action, and dreams of regime change in the hemisphere are the “oldest moves in the American foreign policy playbook,” wrote columnist Gustavo Arellano in the Los Angeles Times. “For more than two centuries, the United States has treated Latin America as its personal piñata, bashing it silly for goods and not caring about the ugly aftermath.”

The story dates back to the US founders, details historian Greg Gambrill in America, América, his new survey of hemispheric relations. “It is impossible not to look forward to distant times” when the US will “cover the whole Northern, if not Southern, continent with a people speaking the same language, governed in similar forms,” Thomas Jefferson wrote.

President James Monroe codified that goal in 1823 in what became the Monroe Doctrine, explained Arellano. “It is known to all that we derive [our blessings] from the excellence of our institutions. Ought we not, then, to adopt every measure which may be necessary to perpetuate them?” Monroe asked.

That doctrine “sanctioned the idea that the United States has a right to project its powers beyond its official borders,” explains Gambrill. The US cited it repeatedly “as a self-issued warrant to intervene against its southern neighbors, from the taking of Texas to more recent efforts at regime change in Venezuela and Nicaragua.” In 1823, the Supreme Court gave its blessing, declaring “conquest gives a title to which the Courts of the conqueror cannot deny.”

Sovereign nations hammered by the US, many of them repeatedly, include Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Mexico was the first target and it remains one to this day. Trump has begun detailed planning to attack drug cartels in Mexico with ground operations, NBC News reported this week. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, whose politics and gender fit the profile of leaders Trump disdains, is unlikely to welcome it. When talk of Trump bombing cartels inside Mexico surfaced this Spring, Sheinbaum said, “we reject any form of intervention or interference.”

Within a few years of the Monroe Doctrine’s enactment, pro-slavery US leaders were encouraging slaveholders to flood northern Mexico, orchestrating a rebellion to form an “independent country” of Texas that was soon absorbed as a US slave state.

President James Polk expanded that acquisition, invading Mexico in 1846, occupying Mexico City, and forcing a massive land grab of up to one-third of Mexican territory, which would become much of the US Southwest. Abraham Lincoln, then in Congress, vehemently opposed the war in speeches and resolutions. Ulysses S. Grant, who served in the war, later reflected, “to this day (I) regard the war as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation.”

For decades after, US expansionists schemed to seize other territory in the hemisphere, including Cuba, Puerto Rico, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Their aspirations came to fruition with the 1898 war against Spain that resulted in a new overseas US empire that included Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam.

In the 20th Century, the interventions and abuses accelerated. President Theodore Roosevelt—backed with J.P. Morgan’s wealth—broke Panama off from Colombia so the US could build and own a canal. Most locals were unaware of their “independence” until “an American officer raised (Panama’s) ‘new flag’,” Grandin notes. Around the same time in Venezuela, a US corporate financier and speculator engineered control of a new asphalt industry, with the help of White House battleships, to feed a road-building boom in the US–shades of future US maneuvers to secure control of resources, including Venezuelan oil, the world’s largest oil reserves.

“Rubber, ivory, and palm-oil; tea, coffee, and cocoa; bananas, oranges, and other fruit; cotton, gold, and copper–they, and a hundred other things which dark and sweating bodies hand up to the white world from pits of slime, pay and pay well,” was how W.E.B. DuBois, described colonialism and racial capitalism, in a 1916 essay, “The Souls of White Folk.”

In 1910, Mexican insurgents overthrew longtime dictator Porfirio Díaz, beginning a tumultuous decade. The new leader, Francisco Madero, was assassinated, with covert US assistance. Meanwhile, US investors, who owned nearly half of all Mexican property value, encouraged US intervention. Newly-elected President Woodrow Wilson, who had campaigned on a peace platform, soon dispatched Marines and sailors to occupy Veracruz, although Wilson subsequently said the US had “no right to intervene in Mexico.”

It wasn't until 1933, under President Franklin Roosevelt, that the US largely paused “the doctrine of conquest and began to abide by the rule of law,” said Grandin in a Nation podcast describing what became known as the “Good Neighbor” policy. “Our Era of Imperialism Nears Its End,” proclaimed the New York Times. Not for long.

By the end of World War II, with an anti-Communist crusade in full force, leftists and social democratic reformers in Latin America became as endangered as those blacklisted and imprisoned at home. Concurrently, US trade policies promoted policies of underdevelopment, resource exploitation, and massive debt.

The CIA campaign to destabilize and overthrow a democratically elected government in Guatemala became a prelude for similar assaults in Cuba’s Bay of Pigs in 1961, Brazil in 1964, the Dominican Republic in 1965, and Chile in 1973. “Washington had a hand in 16 regime changes between 1961 and 1969,” notes Grandin.

It continued, notably with President Ronald Reagan’s offensives in Central America in the 1980s. When the International Court of Justice ruled his contra war in Nicaragua was illegal, Reagan simply withdrew from the ICJ, a flaunting of the post-World War II international law order that US administrations have followed ever since.

In his Nation podcast, Grandin depicts the latest US strikes as “obviously part of Trump's drive to use violence and force and establish dominance in whatever way he can muster” with Venezuela “the entry point to a reverse domino effect” for regime change against left and progressive-leaning governments in the region.

Grandin contrasts US behavior with two centuries of efforts by Latin American and Caribbean liberal leaders in repeated hemispheric conferences to build a very different democratic, non-interventionist model, beginning with a 1826 Panama Congress led by South American independence pioneer Simón Bolívar.

Cuban revolutionary José Martí was a key figure in the First International Conference of American States in 1889-1890. Delegates, other than the US, pushed for consensus opposing wars of aggression and territorial annexation, notes Grandin, around “a general principle that no powerful nation had the right to intervene in any way in the politics of other nations.”

According to Grandin, the lesson from Latin America has been “democracy in Latin America means social democracy. The world's first social democratic constitution was in Mexico. When Latin Americans are asked to define democracy, they talk about healthcare, they talk about education.” And a respect for national sovereignty.