The Other Side of Opportunity: What Immigrants Contribute to US Institutions

We often talk about immigrants as beneficiaries of American opportunity. But in higher education, healthcare, research and beyond, immigrants are also architects of institutional improvement.

The US Department of Education recently withdrew its unlawful directive that would have restricted diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in schools and universities nationwide. The guidance was framed as an attempt to enforce “neutrality” in education. In practice, it would have narrowed how institutions identify and address inequity, discouraging efforts to create learning environments that reflect the realities of an increasingly global student population.

That national debate can feel abstract, just another skirmish in a broader culture war over higher education. But equity is not abstract. It lives in the quiet mechanics of institutions: who gets seen, who gets filtered out, and which barriers are treated as incidental rather than structural. I am reminded of this not by a court ruling or federal directive, but in the ordinary work of teaching and mentoring students from around the world as an assistant professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. It shows up during office hours, committee meetings, and the quiet moments when institutional rules do their work.

Americans are fluent in a familiar story about immigration: Immigrants come to the United States for opportunity—better education, better jobs, better lives. That story is not wrong. But it is incomplete. What is talked about far less is how immigrants improve the institutions they enter, often by exposing the limits of systems that were never designed with them in mind.

Case in point: Like many graduate programs, ours used procedures that filtered out applicants who had not paid an application fee before faculty review. When they failed to pay, I was never supposed to see their application. The fee, common by US standards, was prohibitively expensive in some local currencies. Until I learned about that procedure, I hadn’t fully appreciated how many judgments about who “belongs” in graduate school happen long before any evaluation of research potential or intellectual fit. Once I understood the implications of that policy, I advocated to have it amended, and a student I would never have otherwise met was later admitted and enrolled.

The real work of equity is not expanding opportunity within unchanged systems but interrogating the systems themselves—especially when those systems quietly reward conformity.

That experience crystallized something for me. The student’s presence highlighted how even well-intentioned programs can struggle to value ways of thinking they were never designed to account for. The student, meanwhile, navigated those gaps with a practicality that exposed where the system itself needed adjustment.

The same design logic operates across American institutions that confuse neutrality with fairness. Even institutions that are equity forward, including my own, must navigate a shifting and often constraining federal landscape, making progress real, but necessarily incomplete.

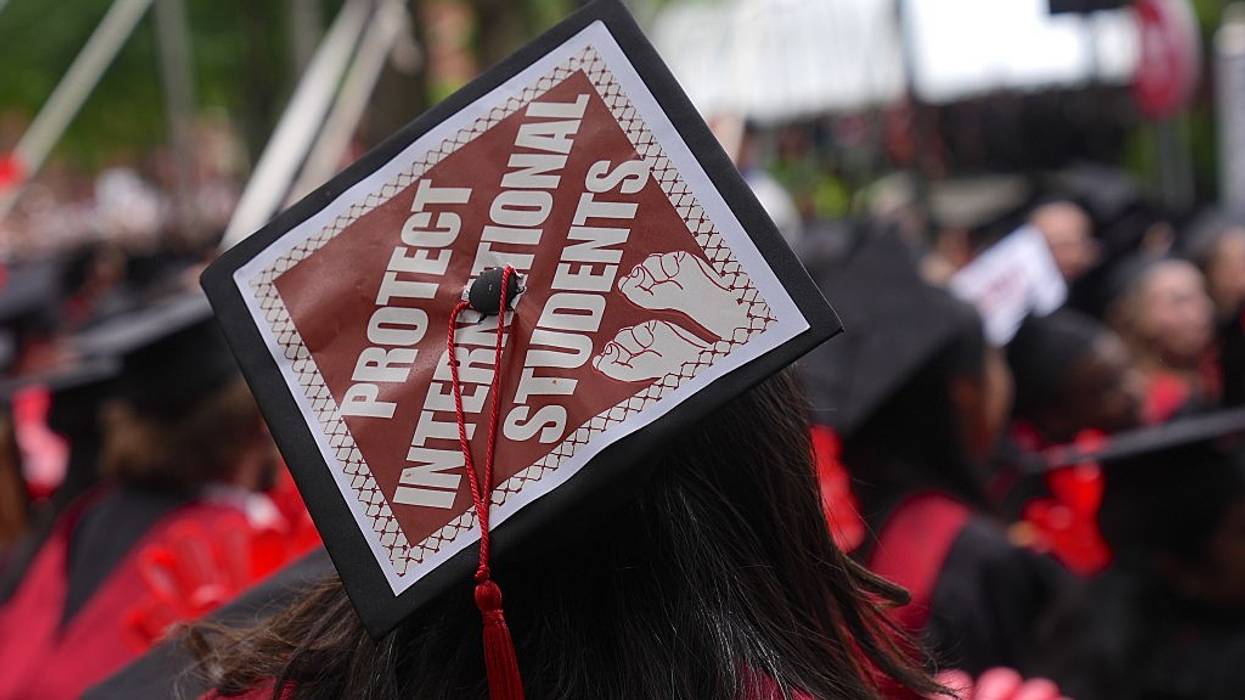

This kind of exclusion is not unique to admissions policies. Across higher education, international students routinely navigate US systems calibrated to financial, cultural, and administrative norms that quietly penalize difference. More than 1 million international students are enrolled in US colleges and universities, and an analysis from the Association of American Universities estimates that international students contribute nearly $44 billion to the US economy annually. Yet research consistently shows that international students experience higher levels of social isolation than their domestic peers.

From a public health perspective, these barriers are not incidental—they are risk factors that function as chronic stressors. Uncertainty around visas, financial precarity, cultural dislocation, and exclusionary policies shape mental health and academic persistence long before a student ever sets foot on campus. Research shows that rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidality among international students have risen sharply over the past decade, even as access to culturally responsive mental health services remains uneven.

In public health, we name these design failures plainly: policy choices—not personal deficits. Improving the experience of international students is less about individual support than about whether institutions are willing to change the conditions they create.

What struck me most, though, was not my student’s resilience in the face of these barriers, but what institutions gain when those barriers are confronted. They were adept at finding workarounds where institutions offered only walls—and unapologetic about pointing out the walls. That resourcefulness did not just help them navigate the system; it revealed where the system itself needed to change.

The real work of equity is not expanding opportunity within unchanged systems but interrogating the systems themselves—especially when those systems quietly reward conformity.

We often talk about immigrants as beneficiaries of American opportunity. But in higher education, healthcare, research and beyond, immigrants are also architects of institutional improvement. They expose inefficiencies, challenge inherited assumptions, and force clarity around what we actually mean by merit.

Immigrants make up a disproportionate share of the US healthcare workforce, including physicians, researchers, and direct-care providers—roles that are essential as the country grapples with workforce shortages and widening health inequities.

Opportunity is not a one-way transaction. Institutions that welcome immigrants while resisting the changes their presence demands are not neutral—they are extractive.

Some people change institutions not by asking for permission, but by refusing explanations that don’t make sense. The question isn’t whether immigrants benefit from coming to the United States—the evidence is clear. The more uncomfortable and more important question is whether institutions are willing to reckon with how much they benefit from immigrants, and whether they are prepared to change to welcome them.