February, 01 2013, 12:29pm EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Michelle Bazie,202-408-1080,bazie@cbpp.org

Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the January Employment Report

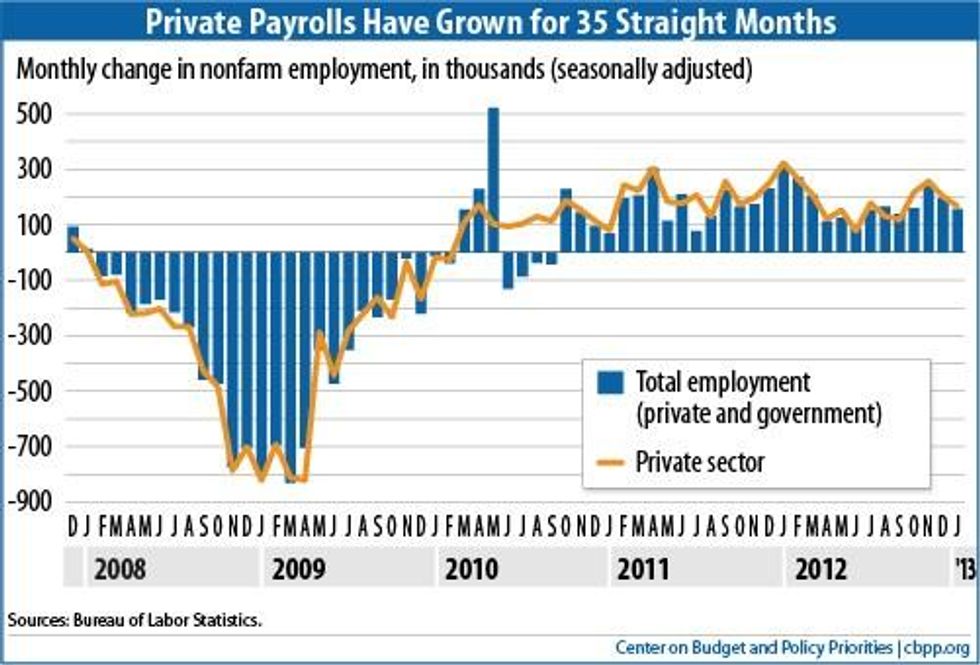

Employers continued to add jobs in January (see chart), but the economy must grow faster to bring unemployment down more quickly. Instead, the recovery apparently has hit a soft patch, and both growth and job creation could slow further if policymakers let the automatic across-the-board budget cuts (known as "sequestration") take effect on March 1 or replace them with other immediate budget cuts that further weaken demand for goods and services.

WASHINGTON

Employers continued to add jobs in January (see chart), but the economy must grow faster to bring unemployment down more quickly. Instead, the recovery apparently has hit a soft patch, and both growth and job creation could slow further if policymakers let the automatic across-the-board budget cuts (known as "sequestration") take effect on March 1 or replace them with other immediate budget cuts that further weaken demand for goods and services.

Economic growth has been modest throughout the recovery, which began in mid-2009. Consequently, the growth to date has not fully erased the huge jobs deficit that the Great Recession created and unemployment remains unacceptably high. With enough demand, the economy could be producing a trillion dollars more output and several million more people could be working.

Earlier this week, the Commerce Department reported that growth in demand for goods and services (measured by final sales) slowed to a modest 1.1 percent annual rate. (Gross domestic product, or GDP, was essentially flat since the growth in final sales was financed out of inventories rather than the production of new goods and services, and, notably, a sharp decline in defense spending took 1.3 percentage points from demand.) The slowdown may have arisen from "weather-related disruptions and other transitory factors," as the Federal Reserve said in this week's monetary policy announcement. But the Fed's decision to continue purchasing government securities in hopes of pushing down long-term interest rates and its expectation that it will keep short-term rates as close to zero as practicable for a considerable time suggest that it expects high unemployment to persist for some time.

The economy's ability to resume stronger growth this year will suffer from the expiration of the payroll tax cut, and could suffer even more from spending cuts due to sequestration or other congressional action -- all of which would further hinder demand. Indeed, part of the sharp decline in defense spending in the fourth quarter may have come from an anticipation of such cuts.

Policymakers missed an opportunity in the recent "fiscal cliff" negotiations to resolve the sequestration issue by adopting policies that achieved equivalent budget savings that were more balanced between taxes and spending and that did not take effect until the economy was stronger. They missed an opportunity to boost the recovery and brighten jobless workers' job prospects when they failed to extend the payroll tax cut. And they missed an opportunity to achieve more deficit reduction that didn't threaten the recovery when they did not end President Bush's tax cuts for more very well-to-do Americans.

They have to do a better job of resolving sequestration this time if they want to enhance prospects of a stronger economic recovery, more job creation, and balanced deficit reduction.

About the January Jobs Report

Job growth moderated in January and the unemployment rate remained just below 8 percent, as it has for the past five months. (Payroll employment data have been revised back to January 2008 to reflect the annual benchmark adjustment for March 2012 and updated seasonal adjustment factors; unemployment and other household survey data for January 2013 reflect updated population estimates and are not directly comparable to earlier data, which have not been revised to incorporate those estimates.)

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 157,000 jobs in January. Private employers added 166,000 jobs, while government employment fell by 9,000. Federal employment fell by 5,000 and local government employment fell by 6,000, while state government employment rose by 2,000.

- This is the 35th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 6.1 million jobs (a pace of 175,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 5.5 million jobs over the same period, or 157,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 606,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 423,000 local government jobs. (These data reflect substantial upward revisions to November and December and incorporation of the new benchmark data for March 2012.)

- Despite 35 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 3.2 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 2.7 million fewer jobs on private payrolls in January than when the recession began in December 2007. Despite job growth averaging 200,000 jobs a month over the past three months, the addition of just 157,000 jobs in January is well short of the 200,000 to 300,000 jobs a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery.

- The unemployment rate was 7.9 percent in January, and 12.3 million people were unemployed. In January, the unemployment rate was 7.0 percent for whites (2.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 13.8 percent for African Americans (4.8 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 9.7 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (3.4 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- Because they reflect the new population estimates, these unemployment data are not directly comparable to those from earlier years. Supplemental data in the January report show, however, that adjusting the December numbers would have had no effect on the unemployment rate and only a small effect on the number of unemployed. The official unemployment rate was been between 7.8 and 7.9 percent over the last four months of 2012 and the number of unemployed was been between 12.0 and 12.2 million.

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force. The labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over who are working or actively looking for work) was 63.6 percent in January, about the same as its 63.7 percent average for 2012. Prior to this latest period, it had not been so low since the early 1980s.

- Using the unofficial adjusted numbers for December, the labor force rose by 7,000 in January, the number of people with a job fell by 110,000, and the number of unemployed rose by 117,000.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.6 percent in January, the same as its average in 2012. (Comparisons of these ratios are little affected by the new population estimates.)

- The Labor Department's most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure -- which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can't find full-time jobs -- was 14.4 percent in January. That's down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in late 2009 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 5.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, roughly 23 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Almost two-fifths (38.1 percent) of the 12.2 million people who are unemployed -- 4.7 million people -- have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.0 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is one of the nation's premier policy organizations working at the federal and state levels on fiscal policy and public programs that affect low- and moderate-income families and individuals.

LATEST NEWS

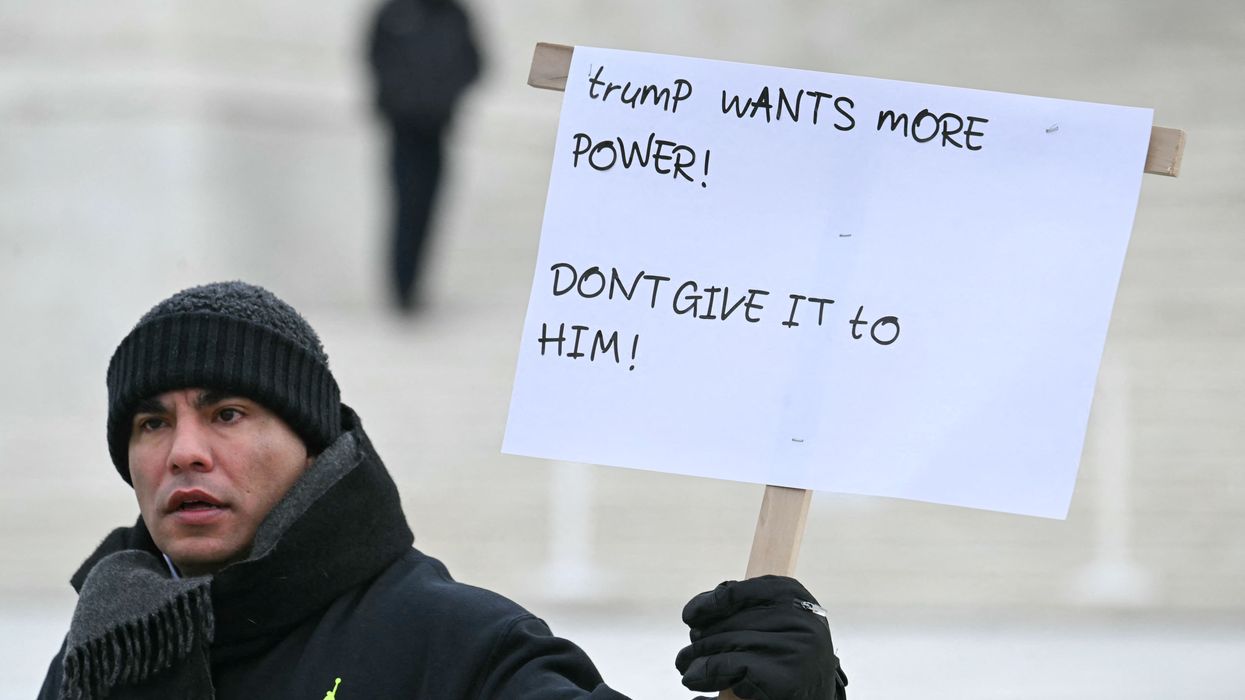

'Grave Danger': Warnings as Supreme Court Looks Ready to Hand Trump Even More Unchecked Power

The court's right-wing majority signaled a willingness to overturn the 90-year-old precedent Humphrey’s Executor—a move that would "enable Donald Trump’s corrupt march toward oligarchy," said one critic.

Dec 08, 2025

The warnings on Monday from the US Supreme Court’s liberal justices were stark as the Trump administration argued in favor of allowing the president to easily fire top officials at federal agencies—a move that would reverse nearly a century of precedent that originated with a unanimous ruling known as Humphrey's Executor in 1935.

"You're asking us to destroy the structure of government," Justice Sonia Sotomayor told Solicitor General D. John Sauer, who argued on behalf of the Trump administration that Humphrey's Executor limits presidential authority in an unconstitutional way even following rulings by the conservative majority that have weakened the decision.

Justice Elena Kagan added that setting aside the precedent and allowing President Donald Trump to fire Federal Trade Commission (FTC) board members and other federal agency leaders would “put massive, uncontrolled, unchecked power in the hands of the president.”

"Once you're down this road, it's a little bit hard to see how you stop," Kagan said.

But the court's right-wing majority signaled little concern about the unchecked authority it could give the president should it rule in Trump's favor in the coming months in Trump v. Slaughter, which centers on the White House's firing of FTC Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, a strong defender of consumer rights in March.

Slaughter has said she was dismissed for being "inconsistent with [the] administration's priorities" as the Department of Government Efficiency was gutting federal agencies and rooting out programs and employees that were also viewed as being in the way of Trump's right-wing agenda.

But under Humphrey's Executor, which was decided after former President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried to remove an FTC member, a president can fire a board member only for "inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office," in accordance with a law passed by Congress in 1914.

The ruling established that the president can remove executive officials without cause, but not at independent agencies that are "neither political nor executive, but predominantly quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative," such as the FTC.

Sauer wrote in a court document that the ruling "was always egregiously wrong," furthering the argument made by right-wing proponents of the "unitary executive" theory—a view that holds that the president should hold absolute power over federal agencies, including by firing leaders they view as opposed to their agenda.

A lawyer for Slaughter, Amit Agarwal of Protect Democracy, told the justices on Monday that "dozens of institutions that have been around for a long time, that have withstood the test of time, that embody a distillation of human wisdom and experience, all of those would go south” if the court allowed the president to hold complete control over agencies.

Undoing Humphrey's Executor would “profoundly destabilize institutions that are now inextricably intertwined with the fabric of American governance," Slaughter's lawyers have argued.

Chief Justice John Roberts signaled an unwillingness to preserve the 90-year-old precedent, calling the ruling a "dried husk" at one point. Right-wing courts and justices have worked to weaken the precedent for more than a decade, with Roberts writing in a 2010 opinion that the president's power should be understood to include “the authority to remove those who assist him in carrying out his duties."

A decade later, the Supreme Court ruled in a 5-4 decision in Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau that the CFPB's structure itself was unconstitutional because the president does not have the authority to fire the director of the independent agency without just cause.

On Monday, Josh Orton, director of judiciary reform group Demand Justice, said there was "grave danger in what the Supreme Court appears willing to do today: hand giant corporations and Donald Trump’s billionaire class unchecked power over our economic system, gutting one of the few institutions left that’s charged with ensuring fairness, stability, and competition in our economy.

“For generations, independent federal agencies, including the Federal Trade Commission and the Federal Reserve, have proven essential to the long-term stability of our country and markets—all to the benefit of workers, consumers, and businesses alike," said Orton.

A lower court ruled earlier this year that Slaughter had been illegally fired, but the Supreme Court in September allowed the dismissal to stand with an emergency order, until the case could be heard.

The Supreme Court has also permitted Trump to move forward, at least temporarily, with the firings of officials at the National Labor Relations Board, the Merit Systems Protection Board, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission.

The justices on Monday signaled that even if they allow the president's firing of Slaughter and the other officials, they may not approve the dismissal of Federal Reserve Gov. Lisa Cook, who the court has permitted to stay in her role despite Trump's attempt to fire her. The court is scheduled to hear a separate case in January regarding Cook's firing.

But Kate Judge, a professor at Columbia Law School, said an overruling of Humphrey's Executor would ultimately have an impact on the Federal Reserve even if the justices carve out an exception.

"[The] Fed's practical independence and the legitimacy needed to sustain it grew alongside the independence of other agencies," said Judge. "It will be hard to maintain faith in one technocratic body while saying the rest are legitimate only because they are directly answerable to the president."

With or without an exception, Orton argued that "a Supreme Court that overturns Humphrey’s Executor and 90 years of precedent to enable Donald Trump’s corrupt march toward oligarchy is simply not a sustainable or legitimate institution.”

Keep ReadingShow Less

IDF Chief Says Ceasefire Line Is a ‘New Border,’ Suggesting Goal to Annex More Than Half of Gaza

Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, a physician and Palestinian leader, said the statement "indicates dangerous Israeli intentions of annexing 53% of the little Gaza Strip, and to prevent reconstruction of what Israel destroyed in Gaza."

Dec 08, 2025

The top-ranking officer in the Israel Defense Forces suggested that Israel may plan to permanently take over more than half of Gaza, which it currently occupies as part of a temporary arrangement under the latest "ceasefire" agreement.

That agreement, signed in early October, required Israel to withdraw its forces behind a so-called "yellow line" as part of the first phase, which left it occupying over half of the territory on its side. Gaza's nearly 2 million inhabitants, meanwhile, are crammed into a territory of about 60 square miles—the vast majority of them displaced and living in makeshift structures.

The deal Israel agreed to in principle says this is only a temporary arrangement. Later phases would require Israel to eventually pull back entirely, returning control to an "International Stabilization Force" and eventually to Palestinians, with only a security buffer zone between the territories under Israel's direct control.

But on Sunday, as he spoke to troops in Gaza, IDF Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Eyal Zamir described the yellow line not as a temporary fixture of the ceasefire agreement, but as “a new border line" between Israel and Gaza.

Zamir stated that Israel has "operational control over extensive parts of the Gaza Strip and we will remain on those defense lines,” adding that "the yellow line is a new border line—serving as a forward defensive line for our communities and a line of operational activity."

The IDF chief did not elaborate further on what he meant, but many interpreted the comments as a direct affront to the core of the ceasefire agreement.

"The Israeli chief of staff said today that the yellow line in Gaza is the new border between Israel and Gaza," said Dr. Mustafa Barghouti, who serves as general secretary of the Palestinian National Initiative, a political party in the West Bank. He said it "indicates dangerous Israeli intentions of annexing 53% of the little Gaza Strip, and to prevent reconstruction of what Israel destroyed in Gaza."

Zamir's statement notably comes shortly after a report from the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor last week provided new details on a US-led proposal to resettle tens of thousands of Palestinians at a time into densely packed "‘cities’ of prefabricated container homes" on the Israeli-controlled side of the yellow line that they would not be allowed to leave without consent from Israel. The group likened the plan to "the historical model of ghettos."

The statement also notably came on the same day that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told German Chancellor Friedrich Merz at a joint press conference that Israel's annexation of the West Bank "remains a subject to be discussed." This year has seen a historic surge of violence by Israeli settlers in the illegally occupied territory, which ramped up following the ceasefire.

Israel has already been accused by Gaza authorities of violating the ceasefire several hundred times by routinely launching strikes in Gaza. On Saturday, the UN reported that at least 360 Palestinians have been killed since the truce went into effect on October 10, and that 70 of them have been children.

The IDF often claims that those killed have been Palestinians who crossed the yellow line. As Haaretz reported last week: "In many cases, the line Israel drew on the maps is not marked on the ground. The IDF's response policy is clear: Anyone who approaches the forbidden area is shot immediately, even when they are children."

On Sunday, Al Jazeera and the Times of Israel reported, citing local medics, that Israeli forces had shot a 3-year-old girl, later identified as Ahed al-Bayok, in southern Gaza’s coastal area of Mawasi, near Khan Younis. The shooting took place on the Hamas-controlled side of the yellow line.

Within the same hour on Sunday, the IDF posted a statement on social media: "IDF troops operating in southern Gaza identified a terrorist who crossed the yellow line and approached the troops, posing an immediate threat to them. Following the identification, the troops eliminated the terrorist." It remains unconfirmed whether that statement referred to al-Bayok, though the IDF has used similar language to describe the shootings of an 8- and 11-year-old child.

Until recently, Israel has also refused to allow for the opening of the Rafah Crossing, the most significant entry point for desperately needed humanitarian aid, which has been required to enter the strip "without interference" as part of the ceasefire agreement.

Israel agreed to open the crossing last week, but only to facilitate the exit of Palestinians from Gaza. In response, eight Arab governments expressed their “complete rejection of any attempts to displace the Palestinian people from their land."

Zamir's comments come as the ceasefire limps into its second phase, where US President Donald Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will push for the full demilitarization of Hamas, which Israel has said would be a precondition for its complete withdrawal from Gaza.

“Now we are at the critical moment," said Qatari Premier and Foreign Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al Thani, at a conference in Doha on Saturday. "A ceasefire cannot be completed unless there is a full withdrawal of the Israeli forces [and] there is stability back in Gaza."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Watchdog Denounces Trump AI Order Seen as Giveaway to Big Tech Billionaire Buddies Like David Sacks

"David Sacks and Big Tech want free rein to use our children as lab rats for AI experiments and President Trump keeps trying to give it to them."

Dec 08, 2025

President Donald Trump is drawing swift criticism after announcing he would be signing an executive order aimed at clamping down on state governments' powers to regulate the artificial intelligence industry.

In a Monday morning Truth Social post, Trump said that the order was needed to prevent a fragmented regulatory landscape for AI companies.

"We are beating ALL COUNTRIES at this point in the race, but that won’t last long if we are going to have 50 States, many of them bad actors, involved in RULES and the APPROVAL PROCESS," the president wrote. "THERE CAN BE NO DOUBT ABOUT THIS! AI WILL BE DESTROYED IN ITS INFANCY! I will be doing a ONE RULE Executive Order this week. You can’t expect a company to get 50 Approvals every time they want to do something."

Although specifics on the Trump AI executive order are not yet known, a draft order that has been circulating in recent weeks would instruct the US Department of Justice to file lawsuits against states that pass AI-related regulations with the ultimate goal of overturning them.

Emily Peterson-Cassin, policy director at watchdog Demand Progress, slammed Trump over the looming AI order, which she said was a giveaway to big tech industry billionaire backers such as David Sacks, a major Trump donor who currently serves as the administration's czar on AI and cryptocurrency.

"David Sacks and Big Tech want free rein to use our children as lab rats for AI experiments and President Trump keeps trying to give it to them," she said. "Right now, state laws are our best defense against AI chatbots that have sexual conversations with kids and even encourage them to harm themselves, deepfake revenge porn, and half-baked algorithms that make decisions about our employment and health care."

Peterson-Cassin went on to say that blocking state-level regulations of AI "only makes sense if the president’s goal is to please the Big Tech elites who helped pay for his campaign, his inauguration and his ballroom."

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.) also accused Trump of selling out Americans to do the bidding of Silicon Valley oligarchs.

"This is a direct ask from Big Tech lobbyists (who also donated millions to Trump’s campaign and ballroom) who only care about their own profits, not our safety," Jayapal wrote in a social media post. "States must be able to regulate AI to protect Americans."

Some critics of the Trump AI order questioned whether it had any legal weight behind it. Travis Hall, the director for state engagement at the Center for Democracy and Technology, told the New York Times that Trump's order should not hinder state governments from passing and enforcing AI industry regulations going forward.

“The president cannot pre-empt state laws through an executive order, full stop,” Hall argued. “Pre-emption is a question for Congress, which they have considered and rejected, and should continue to reject.”

Matthew Stoller, an antitrust advocate and researcher at the American Economic Liberties Project, also expressed doubt that Trump's order would be effective at blocking state AI regulations.

"Trump can issue an executive order mandating it rain today, it doesn't really matter though," said Stoller.

Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) predicted the Trump order would be repeatedly struck down in courts.

"Trump’s one rule executive order on AI will fail," Lieu posted on social media. "Executive orders cannot create law. Only Congress can do so. That’s why Trump tried twice (and failed) to put AI preemption into law. Courts will rule against the EO because it will largely be based on a bill that failed."

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular