SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Sam Husseini, (202) 347-0020;

or David Zupan, (541) 484-9167

MYRNA PEREZ

WENDY WEISER

MYRNA PEREZ

WENDY WEISER

Perez is counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law and the author of the report "Voter Purges."

Weiser is the deputy director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan

Center. The Brennan Center is today releasing one of the first

systematic examinations of voter purging -- the practice of removing

voters from registration lists in order to update state registration

rolls.

The center performed a study of purge practices in twelve states:

Florida, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, New York, Ohio,

Oregon, Pennsylvania, Washington, and Wisconsin. The report states that

"election officials across the country are routinely striking millions

of voters from the rolls through a process that is shrouded in secrecy,

prone to error, and vulnerable to manipulation."

Perez stated: "Purges can be an important way to ensure that voter

rolls are dependable, accurate and up-to-date. Far too frequently,

however, eligible, registered citizens show up to vote and discover

their names have been removed from the voter lists because election

officials are maintaining their voter rolls with little accountability

and wildly varying standards. ... Our report finds the following:

According to the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, between 2004 and

2006, thirty-nine states and the District of Columbia reported purging

more than 13 million voters from registration rolls. ... Voter Purges

finds four problematic practices with voter purges that continue to

threaten voters in 2008: purges rely on error-ridden lists; voters are

purged secretly and without notice; bad 'matching' criteria mean that

thousands of eligible voters will be caught up in purges; and

insufficient oversight leaves voters vulnerable to erroneous or

manipulated purges. The report reveals that purge practices vary

dramatically from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, that there is a lack of

consistent protections for voters, and that there are often

opportunities for mischief and mistakes in the purge process."

Weiser added: "The voter rolls are the gateway to voting, and a citizen

typically cannot cast a vote that will count unless his or her name

appears on the rolls. Purges remove names from the voter rolls,

typically preventing wrongfully purged voters from having their votes

counted. Given the close margins by which elections are won, the number

of people wrongfully purged can make a difference. We should not

tolerate purges that are conducted behind closed doors, without public

scrutiny, and without adequate recourse for affected voters."

The report provides some examples of recent purges which were made public:

* In Mississippi earlier this year, a local election official

discovered that another official had wrongly purged 10,000 voters from

her home computer just a week before the presidential primary.

* In Muscogee, Georgia this year, a county official purged 700 people

from the voter lists, supposedly because they were ineligible to vote

due to criminal convictions. The list included people who claimed to

have never even received a parking ticket.

* In Louisiana, including areas hit hard by hurricanes, officials

purged approximately 21,000 voters, ostensibly for registering to vote

in another state, without sufficient voter protections.

* In 2004, Florida planned to remove 48,000 "suspected felons" from its

voter rolls even though many of those identified were in fact eligible

to vote. When the flawed process generated a list of 22,000 African

Americans to be purged and only 61 voters with Hispanic surnames, in

spite of Florida's sizable Hispanic population, it took pressure from

voting rights groups to stop Florida officials from using the purge

list.

A nationwide consortium, the Institute for Public Accuracy (IPA) represents an unprecedented effort to bring other voices to the mass-media table often dominated by a few major think tanks. IPA works to broaden public discourse in mainstream media, while building communication with alternative media outlets and grassroots activists.

"The only beneficiaries will be polluting industries, many of which are among President Trump’s largest donors,” the lawmakers wrote.

A group of 31 Democratic senators has launched an investigation into a new Trump administration policy that they say allows the Environmental Protection Agency to "disregard" the health impacts of air pollution when passing regulations.

Plans for the policy were first reported on last month by the New York Times, which revealed that the EPA was planning to stop tallying the financial value of health benefits caused by limiting fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone when regulating polluting industries and instead focus exclusively on the costs these regulations pose to industry.

On December 11, the Times reported that the policy change was being justified based on the claim that the exact benefits of curbing these emissions were “uncertain."

"Historically, the EPA’s analytical practices often provided the public with false precision and confidence regarding the monetized impacts of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and ozone," said an email written by an EPA supervisor to his employees on December 11. “To rectify this error, the EPA is no longer monetizing benefits from PM2.5 and ozone.”

The group of senators, led by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), rebuked this idea in a letter sent Thursday to EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin.

"EPA’s new policy is irrational. Even where health benefits are 'uncertain,' what is certain is that they are not zero," they said. "It will lead to perverse outcomes in which EPA will reject actions that would impose relatively minor costs on polluting industries while resulting in massive benefits to public health—including in saved lives."

"It is contrary to Congress’s intent and directive as spelled out in the Clean Air Act. It is legally flawed," they continued. "The only beneficiaries will be polluting industries, many of which are among President [Donald] Trump’s largest donors."

Research published in 2023 in the journal Science found that between 1999 and 2020, PM2.5 pollution from coal-fired power plants killed roughly 460,000 people in the United States, making it more than twice as deadly as other kinds of fine particulate emissions.

While this is a staggering loss of life, the senators pointed out that the EPA has also been able to put a dollar value on the loss by noting quantifiable results of increased illness and death—heightened healthcare costs, missed school days, and lost labor productivity, among others.

Pointing to EPA estimates from 2024, they said that by disregarding human health effects, the agency risks costing Americans “between $22 and $46 billion in avoided morbidities and premature deaths in the year 2032."

Comparatively, they said, “the total compliance cost to industry, meanwhile, [would] be $590 million—between one and two one-hundredths of the estimated health benefit value."

They said the plan ran counter to the Clean Air Act's directive to “protect and enhance the quality of the Nation’s air resources so as to promote the public health and welfare,” and to statements made by Zeldin during his confirmation hearing, where he said "the end state of all the conversations that we might have, any regulations that might get passed, any laws that might get passed by Congress” is to “have the cleanest, healthiest air, [and] drinking water.”

The senators requested all documents related to the decision, including any information about cost-benefit modeling and communications with industry representatives.

"That EPA may no longer monetize health benefits when setting new clean air standards does not mean that those health benefits don’t exist," the senators said. "It just means that [EPA] will ignore them and reject safer standards, in favor of protecting corporate interests."

"An unmistakable majority wants a party that will fight harder against the corporations and rich people they see as responsible for keeping them down," wrote the New Republic's editorial director.

Democratic voters overwhelmingly want a leader who will fight the superrich and corporate America, and they believe Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is the person to do it, according to a poll released this week.

While Democrats are often portrayed as squabbling and directionless, the poll conducted last month by the New Republic with Embold Research demonstrated a remarkable unity among the more than 2,400 Democratic voters it surveyed.

This was true with respect to policy: More than 9 in 10 want to raise taxes on corporations and on the wealthiest Americans, while more than three-quarters want to break up tech monopolies and believe the government should conduct stronger oversight of business.

But it was also reflected in sentiments that a more confrontational governing philosophy should prevail and general agreement that the party in its current form is not doing enough to take on its enemies.

Three-quarters said they wanted Democrats to "be more aggressive in calling out Republicans," while nearly 7 in 10 said it was appropriate to describe their party as "weak."

This appears to have translated to support for a more muscular view of government. Where the label once helped to sink Sen. Bernie Sanders' (I-Vt.) two runs for president, nearly three-quarters of Democrats now say they are either unconcerned with the label of "socialist" or view it as an asset.

Meanwhile, 46% said they want to see a "progressive" at the top of the Democratic ticket in 2028, higher than the number who said they wanted a "liberal" or a "moderate."

It's an environment that appears to be fertile ground for Ocasio-Cortez, who pitched her vision for a "working-class-centered politics" at this week's Munich summit in what many suspected was a soft-launch of her presidential candidacy in 2028.

With 85% favorability, Bronx congresswoman had the highest approval rating of any Democratic figure in the country among the voters surveyed.

It's a higher mark than either of the figures who head-to-head polls have shown to be presumptive favorites for the nomination: Former Vice President Kamala Harris and California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Early polls show AOC lagging considerably behind these top two. However, there are signs in the New Republic's poll that may give her supporters cause for hope.

While Harris is also well-liked, 66% of Democrats surveyed said they believe she's "had her shot" at the presidency and should not run again after losing to President Donald Trump in 2024.

Newsom does not have a similar electoral history holding him back and is riding high from the passage of Proposition 50, which will allow Democrats to add potentially five more US House seats this November.

But his policy approach may prove an ill fit at a time when Democrats overwhelmingly say their party is "too timid" about taxing the rich and corporations and taking on tech oligarchs.

As labor unions in California have pushed for a popular proposal to introduce a billionaire's tax, Newsom has made himself the chiseled face of the resistance to this idea, joining with right-wing Silicon Valley barons in an aggressive campaign to kill it.

While polls can tell us little two years out about what voters will do in 2028, New Republic editorial director Emily Cooke said her magazine's survey shows an unmistakable pattern.

"It’s impossible to come away from these results without concluding that economic populism is a winning message for loyal Democrats," she wrote. "This was true across those who identify as liberals, moderates, or progressives: An unmistakable majority wants a party that will fight harder against the corporations and rich people they see as responsible for keeping them down."

In some cases, the administration has kept immigrants locked up even after a judge has ordered their release, according to an investigation by Reuters.

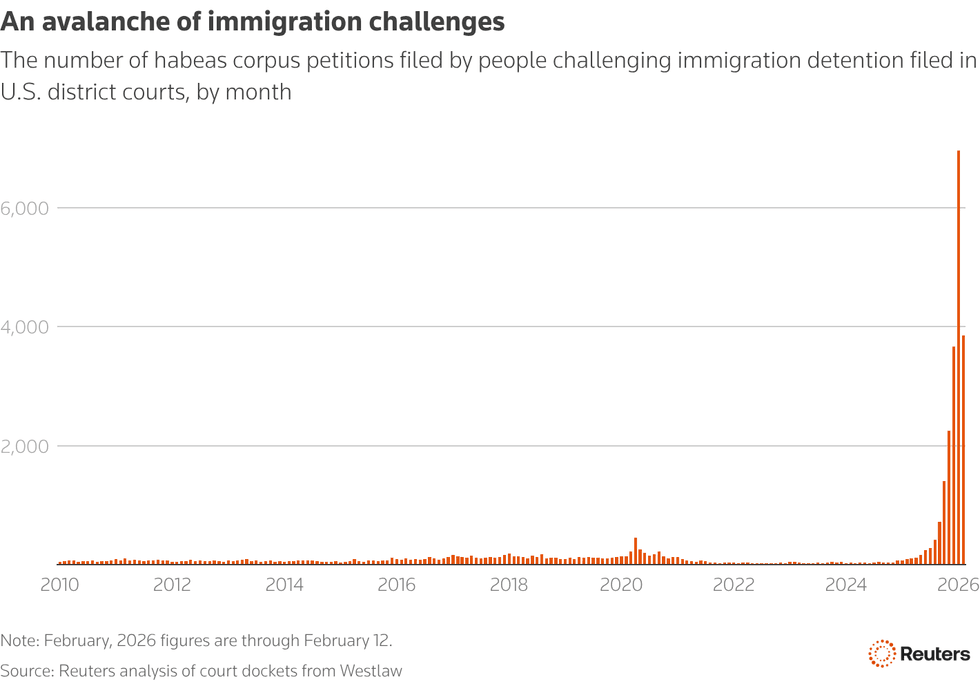

Judges across the country have ruled more than 4,400 times since the start of October that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement has illegally detained immigrants, according to a Reuters investigation published Saturday.

As President Donald Trump carries out his unprecedented "mass deportation" crusade, the number of people in ICE custody ballooned to 68,000 this month, up 75% from when he took office.

Midway through 2025, the administration had begun pushing for a daily quota of 3,000 arrests per day, with the goal of reaching 1 million per year. This has led to the targeting of mostly people with no criminal records rather than the "worst of the worst," as the administration often claims.

Reuters' reporting suggests chasing this number has also resulted in a staggering number of arrests that judges have later found to be illegal.

Since the beginning of Trump's term, immigrants have filed more than 20,200 habeas corpus petitions, claiming they were held indefinitely without trial in violation of the Constitution.

In at least 4,421 cases, more than 400 federal judges have ruled that their detentions were illegal.

Last month, more than 6,000 habeas petitions were filed. Prior to the second Trump administration, no other month dating back to 2010 had seen even 500.

In part due to the sheer volume of legal challenges, the Trump administration has often failed to comply with court rulings, leaving people locked up even after judges ordered them to be released.

Reuters' new report is the most comprehensive examination to date of the administration's routine violation of the law with respect to immigration enforcement. But the extent to which federal immigration agencies have violated the law under Trump is hardly new information.

In a ruling last month, Chief Judge Patrick J. Schiltz of the US District Court in Minnesota—a conservative jurist appointed by former President George W. Bush—provided a list of nearly 100 court orders ICE had violated just that month while deployed as part of Trump's Operation Metro Surge.

The report of ICE's systemic violation of the law comes as the agency faces heightened scrutiny on Capitol Hill, with leaders of the agency called to testify and Democrats attempting to hold up funding in order to force reforms to ICE's conduct, which resulted in a partial shutdown beginning Saturday.

Following the release of Reuters' report, Rep. Ted Lieu (D-Calif.) directed a pointed question over social media to Kristi Noem, the secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE.

"Why do your out-of-control agents keep violating federal law?" he said. "I look forward to seeing you testify under oath at the House Judiciary Committee in early March."