Retired Military Officers, Serve Your Country Once More by Standing Up to Trump

Once these former generals and admirals and other high officers take a united stand, they will receive great mass media attention and give great credibility to the expanding peaceful opposition to Trump.

As President Donald Trump’s dictatorial grip over America worsens, his violations of our Constitution, federal laws, and international treaties become more brazen. Only the organized people can stop this assault on our democracy by firing him, through impeachment, the power accorded to Congress by our Founders. This is one of the few things that he cannot control.

According to a PRRI’s (Public Religion Research Institute) poll, “a majority of Americans (56%) agree that ‘President Trump is a dangerous dictator whose power should be limited before he destroys American democracy’ up from 52% in March 2025.” Trump’s recent actions will only further increase this number.

In earlier columns, I discussed the potential power of

- The Contented Classes;

- The small minority of progressive billionaires; and

- The huge potential of the four ex-presidents–George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama, and Joe Biden, who detest Trump but are mostly silent, and are not organizing their tens of millions of angry voters in all Congressional Districts.

A fourth formidable constituency, if organized, is retired military officers who have their own reasons for dumping Trump. Start with the ex-generals whom Trump named as Secretary of Defense (James Mattis); John Kelly, as US Secretary of Homeland Security and White House Chief of Staff; and Mark Milley, who headed the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

High military brass have sworn to uphold the Constitution, which does not allow for monarchs or dictators.

Trump introduced many nominees with sky-high praise. When they tried to do their job and restrain Trump’s lawlessness, slanders, and chronic lies to the public, his attitude toward them cooled, and then he savaged them. Ultimately, he fired several of them in his first term.

During a November 2018 trip to France to mark the WWI armistice centennial, Trump canceled a planned visit to the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery, where many Americans killed at Belleau Wood are buried. Trump said he canceled the visit to the cemetery because of the rain. The Atlantic magazine reported that Trump claimed that “‘the helicopter couldn’t fly’ and that the Secret Service wouldn’t drive him there. Neither claim was true.” Trump especially disliked Kelly saying about Trump that “a person that thinks those who defend their country in uniform, or are shot down or seriously wounded in combat, or spend years being tortured as POWs are all ‘suckers’ because ‘there is nothing in it for them.’” This sentiment, coming from Trump, a serial draft dodger, rankled Kelly. (Of course, the persistent prevaricator Trump denied saying these words.)

The retired military officers’ case against Trump is too long to list fully. They were, however, summarized by one retiree, who cited the military code of justice and declared that were he to be tried under that code, Trump would be court-martialed and jailed many times over. Consider some of the would-be charges: constant lying about serious matters, including his own illegal acts; using his office to enrich himself; unconstitutionally and illegally bombing countries that do not threaten the United States; using federal troops inside our country; and escalating piracy on the high seas, with misuse of the US Coast Guard.

Moreover, they resent deeply how Trump came into his second term, enabled by the feeble Democratic Party, and fired career generals for no cause other than to replace them with his cronies and sycophants. This includes firing the highly regarded first woman to head the Coast Guard. He has discarded the policy aimed at ensuring the military reflects America’s diversity by providing equal opportunities for women and minorities to serve.

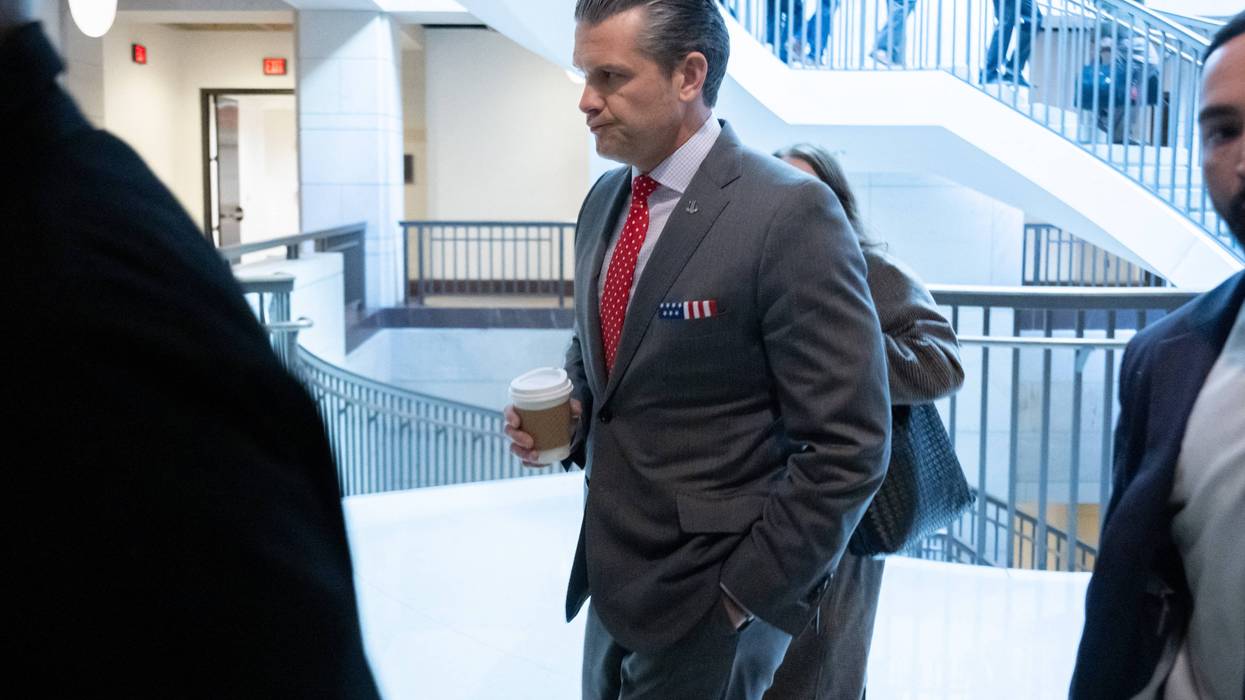

Retired military officers despise Pete Hegseth, the incompetent, foul-mouthed puppet secretary of defense, for his mindless aggressions, misogyny, and mistreatment or forcing out of long-time public servants in the Pentagon. They find it appalling that Trump’s statement that the six ex-military members of Congress who reminded US soldiers not to obey an illegal order (long part of the Military Code of Justice and other laws) should be executed. This impeachable outburst was followed by Hegseth moving to punish Sen. Mark Kelly (D-Ariz.), one of the signers, by seeking to lower his reserve rank and reduce his pension.

They also resent Trump reducing services at the VA due to mass layoffs.

What could be keeping these officers on the sidelines? Many of the very top brass have become consultants to the weapons manufacturers. Others fear retribution affecting their retirement. Others want to avoid the Trumpian incitement to his extreme loyalists to use the internet anonymously to attack any critics.

None of the above should be controlling factors. After all, these officers were expected to face the dangers of any military battle courageously.

Retired Colonel Larry Wilkerson, former chief of staff of Secretary of State Colin Powell, has been outspoken in the media against Trump’s dangerous policies for years. There are others who have taken on Trump, the White House Bully-in-Chief.

Besides, the Republic’s existence is urgently at stake here. Trump is overthrowing the federal government, invading America’s cities with his growing corps of storm troopers, while threatening to go much further with his mantra, “This is just the beginning.” High military brass have sworn to uphold the Constitution, which does not allow for monarchs or dictators.

Once these former generals and admirals and other high officers take a united stand, they will receive great mass media attention. They will give great credibility to the expanding peaceful opposition to Trump. They will provide the needed backbone to the Democrats in Congress to hold shadow hearings to press for impeachment and removal from office Fuhrer Trump, who daily provides Congress with openly boastful impeachable actions.

For example, he told the New York Times on January 9, 2026, that only “my own morality. My own mind.” restrains him. Not the Constitution, not federal laws and regulations, not treaties we have signed under Republican and Democratic presidents.

He took an oath to obey the Constitution and violated it from Day One.

Stepping forward with an adequate staff, funds that would be raised instantly, the fired generals would bring out retired officers and veterans down the ranking ladder all over the country. Already, Veterans for Peace, with over 100 chapters, is ready for rapid expansion. (See, https://www.veteransforpeace.org/).

Remember this: TRUMP’S DICTATORIAL RAMPAGE IS ONLY GOING TO GET WORSE, MUCH WORSE. Venezuela, Cuba, Panama, Greenland, Nigeria, and Iran are on the growing list for Trump’s endless warmongering. He has openly declared more than once, “Nothing can stop me.” Those words should be sufficient for enough top retired military officers to exert their special legacy of patriotism for the “United States of America and the Republic for which it stands…”