Understanding why rising electricity demand from data centers is a serious problem requires more than a glance at your latest utility bill. Energy isn’t just one of many inputs into the economy; in effect, it is the economy, since doing anything requires it. Of all the energy used in the US and globally, only a little over 20% is in the form of electricity; the rest entails the direct burning of fossil fuels (most electricity is generated also by burning fossil fuels; in the US, 60% of electricity comes from fossil fuel sources—mostly natural gas). Electricity is not a direct source of energy; it’s an energy carrier. But, for households and industries alike, it is an extremely useful way of conveying energy to end users. Just flip a switch or push a button, and electricity makes something happen. It does many things for us, but its role in enabling communications and data processing gives electricity a pivotal importance in the overall energy mix of modern society.

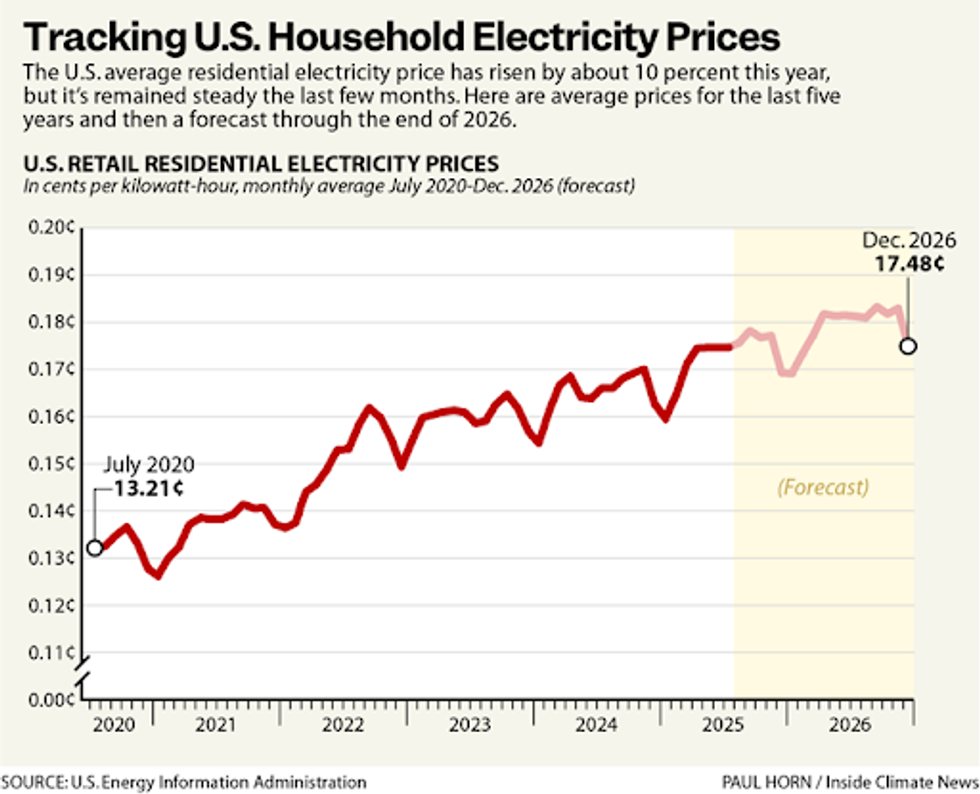

Energy usage for data processing and communications doesn’t tend to rise and fall in response to short-term changes in power prices; economists call it “inelastic.” So, when electricity prices soar, households and businesses must adjust. For households, that typically means buying fewer discretionary consumer products; for businesses, it means raising prices for services or goods. The whole economy grinds slower. We have a storied history of recessions in 1973, 1979, and 2008 that were related to rising fossil fuel prices impacting the entire economy (see photos of gasoline lines and shortages from 1973). What happened with fossil fuels could happen with electricity: As electricity assumes a central role in our energy system, future price spikes could conceivably be as crippling as the OPEC oil embargoes of the 1970s.

A bursting AI bubble could at least temporarily halt electricity price increases tied to new data centers. But it might be a dreadful “solution,” especially for people who are neither wealthy nor politically connected.

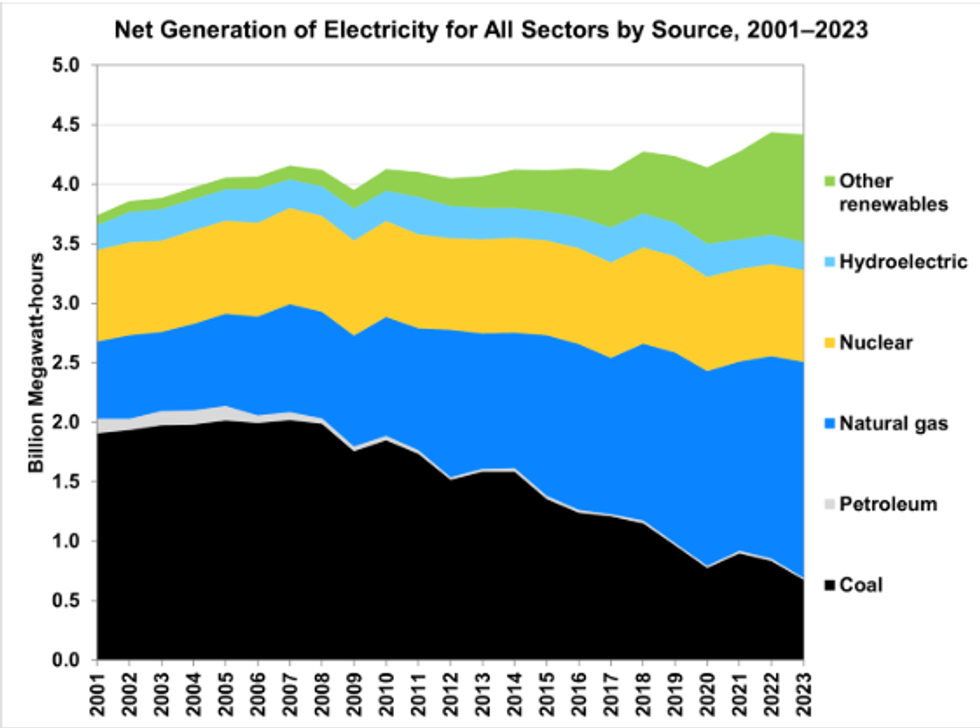

Growing electricity demand for data centers is also a problem because of climate change. Almost all of society’s “progress” in reducing emissions has been in the electricity generation sector (e.g., using solar panels instead of coal to generate electricity). But if electricity demand grows fast, that makes it harder to continue increasing renewables’ share of electricity generation: Demand spikes put utility companies in panic mode, so they deploy any new generating capacity they can quickly obtain—and, so far, they’re resorting to new natural gas turbines more often than new wind projects or solar arrays.

Data centers may be a largely unforeseen disruption to an enormous project that energy planners call the energy transition. As society moves away from fossil fuels, more of its energy usage will occur via electricity—which is the energy output of solar panels, wind turbines, and hydroelectric dams. The transition depends on an ongoing electrification of the economy, starting with electric vehicles. With data centers sucking up so much electricity, it becomes all the harder to deploy electricity to other uses and sectors, which is what planners had been counting on.

Electricity prices can’t keep going up and up. Something’s got to give. Let’s first explore the more obvious solutions to the electricity price dilemma, and then the systemic limits and countervailing trends that will determine which of those solutions is more feasible and likely. I’ll finish by proposing a hybrid supply-demand response that would minimize the economic pain of high electricity prices while putting the country on a more sustainable path.

More Electricity Demand? Just Increase Supply!

The obvious solution to rising electricity prices is to meet new demand with new supply. Just generate more power. What energy sources are available for that purpose?

(US electricity generation by energy source, US Department of Energy. The Trump DoE may have stopped updating its data, as its website features no graph carrying these trendlines forward to 2024.)

(US electricity generation by energy source, US Department of Energy. The Trump DoE may have stopped updating its data, as its website features no graph carrying these trendlines forward to 2024.)

- Natural gas is currently the main energy source for electricity generation in the US, and its share of total generation has grown sharply in recent years. Also, the US is the world’s biggest gas producer. Further, natural gas is the cleanest-burning fossil fuel, though it still produces carbon emissions. These factors together make natural gas the obvious solution for most utility companies. But there are some caveats regarding the future of natural gas, which we’ll unpack in the next section when we explore limits and countertrends.

- Nuclear power has been stagnant in the US for the past three decades: 12 commercial reactors were retired between 2013 and 2021, and two new ones (in Georgia) were recently put into service. The average age of US nuclear plants is 42 years. The nuclear industry, eager for a comeback, has proposed construction of small modular reactors (SMRs) that would allegedly be cheaper and safer than existing nuclear plants, which typically have been slow and costly to build and have been targeted by citizen opposition due to safety concerns. However, the industry’s rosy claims for SMRs are disputed. In the meantime, Microsoft has partnered with the owners of the Three Mile Island nuclear facility, site of the worst nuclear disaster in US history.

- Renewables consist mostly of solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal. Power generation in this sector is expanding quickly, but likely not enough to avert supply shortages or price spikes if AI keeps growing at its current pace. The Trump administration is doing all it can to stall the further expansion of renewables, which continues despite these headwinds. President Donald Trump’s opposition to renewables appears to be political rather than economic, perhaps aimed to repay campaign donations from fossil fuel companies. The oil industry’s drilling technology could be used for deep geothermal electricity generation, the potential scale of which is enormous. The first commercial plants are now under construction; upfront costs are projected to be high, with low and stable operational costs. However, scaling up deep geothermal production to a significant fraction of the nation’s electricity supply might take decades.

- Coal has seen a dramatic and relentless fall in its share of overall power generation in the US (though not in China or India). This is due not just to the pollution and climate policies of previous federal administrations. Fuel supply issues (most of America’s higher-quality coal is already largely depleted), together with cheaper natural gas, have persuaded most electric utility companies that coal is a fuel of the past. The Trump administration is calling for a return to coal, but few utility companies appear to be listening. That’s likely because the federal push for new coal power plants seems driven more by an appeal to voters in mining states like West Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, and Wyoming than by economics.

None of those supply solutions seems ideal. Moreover, before we try to choose a candidate and say, “Problem solved,” it’s essential that we examine limits and countertrends that could cause the current electricity price trajectory to shift.

Why the Electricity Price Trend Could Change

US electricity prices could rise even faster, or the current trend could go into reverse and electricity could get cheaper. What are the foreseeable limits or countertrends that could lead to either of those outcomes?

One factor is natural gas prices, which have been relatively low and stable for the past couple of decades; indeed, adjusted for inflation, they have declined significantly. This has been due to rising North American shale gas supplies released by fracking. Cheap natural gas, in turn, has kept US electricity prices relatively stable until recently. Now, however, two factors are contributing to a likely increase in natural gas prices.

The first is the growth of the US liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry. Currently Europe is, for political and security reasons, phasing out Russian natural gas delivered by pipeline. Instead, Europeans are buying more LNG imported by tanker, a costly substitute. Gas producers in the US, flush with shale gas, are eager to serve these new customers, who are willing to pay much more for natural gas than Americans do currently. So, new LNG export terminals are springing up on the US Gulf Coast, with some already shipping their first cargoes. With a growing share of US natural gas being exported (projected to be over 10% of total production by 2030), domestic prices for the fuel will likely rise, forcing gas-burning utility companies to hike up electricity prices further and faster.

When the people own the means of generation, they can collectively decide to promote renewables over fossil fuels as a source of power.

Meanwhile, America’s shale gas miracle may soon start to peter out. As I noted in a recent article, shale gas fields suffer from rapid depletion of individual wells and thus require high rates of drilling. Most US shale gas regions have already passed their peak of production and are in their plateau or decline phase of extraction. One prominent resource analytics firm forecasts that total US shale gas production will peak between 2027 and 2030. If natural gas production falls, it may be difficult for other electricity sources to grow fast enough to avert power supply problems or rate hikes.

A factor that could conceivably slow electricity price increases, or perhaps even cause prices to fall, is investors’ potential unwillingness to further finance the build-out of AI. In recent months, many Wall Street analysts have expressed dismay at the expanding gap between AI spending—projected to hit $1.5 trillion this year—and actual revenues for companies developing and using AI. Many investors now believe AI stocks are a financial bubble whose bursting could cause a recession or depression for the entire US economy, even the global economy.

A bursting AI bubble could at least temporarily halt electricity price increases tied to new data centers. But it might be a dreadful “solution,” especially for people who are neither wealthy nor politically connected. Past financial crises have been stanched with bailouts for banks and investors, thereby transferring wealth from the public to risk-taking entrepreneurs, while ordinary folks deal with job losses and vanishing retirement nest eggs.

A Better Solution to Unaffordable Electricity

Any realistic solution to soaring electricity prices must address both supply and demand.

Supply: Of the sources of energy for electricity generation, renewables make the most sense, even though they are subject to their own limits and drawbacks, including unsustainable requirements for scarce raw materials and major concerns about environmental, social, health, and security impacts.

Demand: Since materials limits mean that electricity generation from renewables cannot be scaled up indefinitely, it is essential that planners identify ways to reduce electricity demand over the long-term.

Investor-owned utilities have an incentive to sell more product so as to generate more profits and returns for investors. Investor ownership is therefore an impediment to stabilizing electricity supply at a sustainable scale over the long run. Fortunately, there are two other ownership models: electric cooperatives and publicly owned utilities. These kinds of power producers currently supply almost 30% of all US electricity, and typically charge their customers less for power.

When the people own the means of generation, they can collectively decide to promote renewables over fossil fuels as a source of power, as my own local provider, Sonoma Clean Power (SCP), already does.

Community-owned power companies can also promote the reduction of electricity demand. For example, SCP incentivizes the purchase of energy-efficient electric appliances, rooftop solar, and EVs. States can also help with demand reduction; for example, the State of California provides rebates for home efficiency measures.

Here’s another demand reduction strategy, one that’s tailored to the specifics of our current dilemma: States and counties could refuse to grant building permits for new data centers. Failing that, they could wall off AI’s rising electricity demand from electricity markets by requiring data center builders to provide dedicated power plants not connected to the grid. Some data center operators are already doing this, though only a tiny minority so far; most of the off-grid generators rely on natural gas.

This strategy will likely face pushback. The Trump administration is working on ways to keep individual states from regulating AI. Further, even if these efforts fail, AI companies can be expected to hire expensive lawyers and lobbying firms to oppose regulations such as a requirement for off-grid power.

But suppose all new data centers do supply their own off-grid generators. If those generators use natural gas, then competition for fuel with grid-tied power plants could raise natural gas prices, again likely causing electricity prices to soar. The best work-around would be to require data centers to build only renewable-energy generators (including deep geothermal). Again, expect pushback.

Altogether, it’s hard to see any of this happening without a broad base of public support, which would in turn require the public to be better informed on energy issues. It would also require leadership from grassroots activists and politicians. It’s a big ask, when there are already plenty of other priorities for problem solvers. However, unless more electric utilities come to be publicly owned, and a large majority of data centers start generating their own off-grid power from renewable sources, electricity price hikes for households and businesses are likely to continue until the AI financial bubble bursts or electricity prices rise enough to cripple the economy.

Electricity is our energy future, but the details of that future are still sketchy. Right now, the picture is being drawn by billionaire investors, but it looks dark and dystopian. Surely more imaginative artists could do better.

(US electricity generation by energy source,

(US electricity generation by energy source,