If one takes a closer look at wealth concentration and the average American’s opportunity to accrue wealth since the 1970s and 1980s, it offers more evidence of how the last few decades of capitalism's development have denied workers a fair share of the tremendous wealth that has been generated. Indeed, a 2023 Rand Corporation analysis revealed that, since 1975, $79 trillion in wealth had been transferred from the bottom 90% to the top 1%. (Massive Wealth Transfer ). This massive redistribution of wealth continues today. In 2023 alone, $3.9 trillion in wealth was siphoned from working Americans to the richest Americans, enough to give every full-time worker in the bottom 90% a $32,000 raise for the year (2023 Wealth Transfer). When it comes to gaining wealth for the average working American, owning a home is the principal path. Home ownership, however, is completely out of reach for the poor and millions more in today's middle class find it unattainable. The median home price to annual income ratio was 5 in 2025. In other words, the median price of a home was equal to 5 years of salary. The ratio was 3.7 in 1985 when a median-price home was $82,800. Today a median-price home is $416,900. Not only is the distribution of wealth radically unequal, the pathway to increased wealth in home ownership has narrowed dramatically.

The political division and violence in America today stems in large measure from a political system whose policies have encouraged radical disparities in incomes and wealth.

These data amply illustrate the crisis poor and increasingly middle income people in the United States face. The poorest Americans, the bottom 20%, simply do not have enough money to meet their daily needs. Nearly a third of all households lives on less than $50,000 annual income (Household Income). In the richest country in the world 36.8 million Americans live in poverty (Poverty), including 9 million children without adequate access to food, shelter and healthcare (Children). At the same time, the more than 900 billionaires in the U.S. have a collective wealth of $6.9 trillion, their wealth increasing 18% in 2025 alone (Fortune). As reported in Forbes, Elon Musk, the richest man in the world, now has wealth of $778 billion (Elon Musk). It would take the average American worker 16 million years to make that much (Extrapolated).

The US government simply has not done enough to ensure that the livelihoods of all Americans are protected in this new Gilded Age. In fact, the government actually provides 40% more benefits to the wealthy than to the impoverished. In his 2023 book Poverty, By America, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Matthew Desmond draws attention to this fact. From recent government data “compiling spending on social insurance, means-tested programs, tax benefits, and financial aid for higher education,” Desmond calculates that the top 20% of income earners on average receives $35,363 in government benefits and individuals in the bottom 20% receive an average $25,733 (p. 99). This reality is a result of policies, policies that benefit wealthy Americans and corporations at the expense of working people. Public policy, in turn, is shaped by corporate lobbying and political contributions as well as professional research that supports goals of the wealthiest and most influential: smaller government, broad corporate deregulation, limited worker protections, and tax breaks favoring the wealthy over working Americans.

It has not always been this way. Between 1947 and 1979, the period when Keynesian economic theory and policies prevailed, “hourly wages grew 2.2 percent. From 1979 to the present, average growth in hourly wages fell to 0.7 percent per year, only one-third of the average rate in the earlier postwar period” (Economic Policy Institute). In the first three decades after WWII labor unions tripled weekly earnings of manufacturing workers across the nation. Collective bargaining gained “for union workers an unprecedented measure of security against old age, illness and unemployment, and, through contractual protections, greatly strengthening their right to fair treatment at the workplace” (Labor Unions). Significantly, one-third of workers (32.3% in 1959) were unionized in this post-war period (Bureau of Labor Statistics ). By 2024, the percentage of wage and salary workers in unions fell to 9.9 percent (Bureau of Labor Statistics). Concentrated wealth, particularly corporate wealth, and government failure to protect workers dampened wages. Also, in the 1950s the statutory taxes on U.S.corporate and personal wealth were much higher, though the effective tax rate was considerably lower due to corporate tax loopholes and rich taxpayers recategorizing income as derived from investments (Tax Rates). The statutory corporate income tax was over 50 percent (Economic Policy Institute). Today it is 21 percent (Corporate Tax). While it is difficult to determine the percentage of taxes actually paid by wealthy individuals and corporations in the early post-war era, it is clear that the statutory personal and corporate income tax is lower today than it was 70 years ago. Of course, enforcement of steeply progressive taxation would make billions of dollars, even trillions, available to fund social programs that distribute income and wealth more fairly.

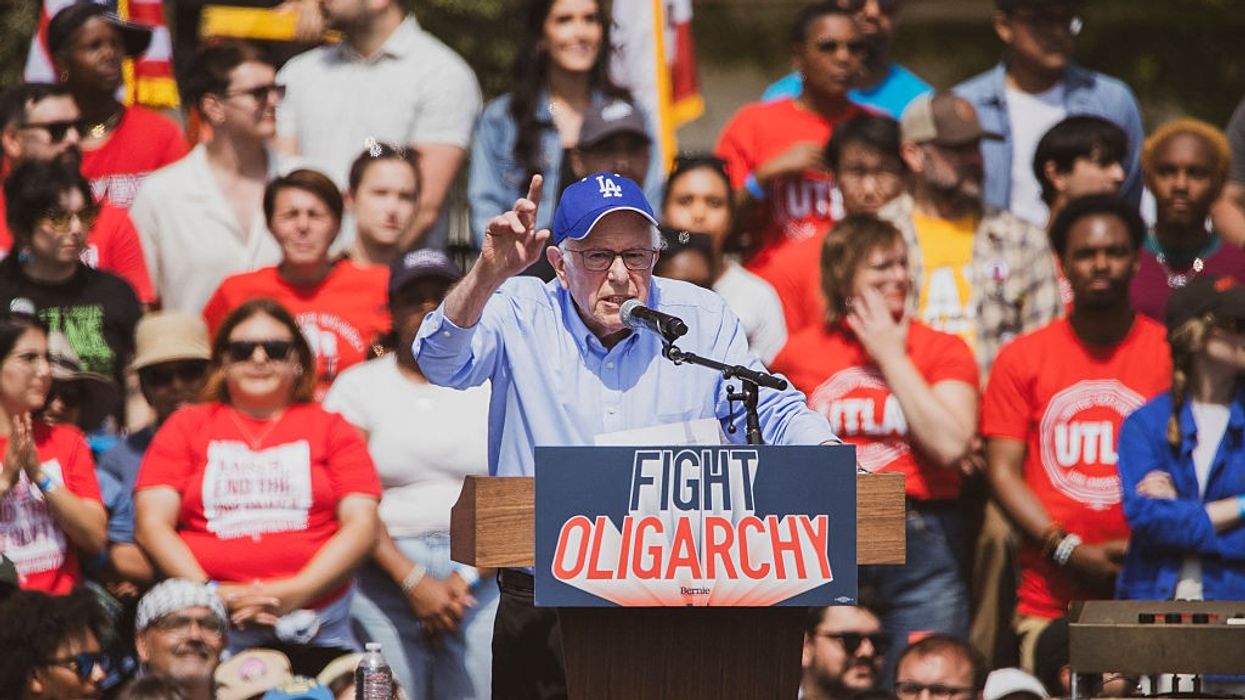

The pro-democracy citizenry must organize around a political vision that emphasizes several political projects: a just, progressive taxation system; a guaranteed household income; universal healthcare; quality public education; free preschool education; and scientific and technological initiatives for a sustainable economy.

A society riven by such income and wealth inequality is inherently unstable. The political division and violence in America today stems in large measure from a political system whose policies have encouraged radical disparities in incomes and wealth. The loss of 6.5 million manufacturing jobs since 1979 (1979 and 2025), for example, has been facilitated by trade agreements that enable corporations to chase the cheapest wages throughout the world. Runaway companies have gutted industrial towns without consequence, leaving behind poorer communities of people with limited resources to rebuild their lives and neighborhoods. The federal government, moreover, has done virtually nothing to force corporations to pay reparations for the social disintegration left in their wake. As the coastal regions and large metropolitan centers of the nation were generally integrated into the surging commerce of unbridled globalization, distant rural regions experienced economic stagnation and decline. It is little wonder that an authoritarian political figure that exploits these divisions has risen to the presidency of the United States.

In his seminal book Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty provides an analysis of capitalism in which he notes that “the history of the distribution of wealth has always been deeply political” (p. 20). Reduction of taxes that favors the wealthy is one political determination reflecting the unstemmed power of concentrated wealth. While this political maneuver undermines a primary income and wealth distributive mechanism (taxation system), it further restricts the resources for funding other re-distributive projects such as social welfare, public education and healthcare. Smaller government and privatization of public services are corollary results.

A principal dynamic factor in the process of wealth accumulation and concentration over the last several decades is the growth of profits as the economic growth rate has slowed down. Put another way, the wealthy are taking a larger and larger slice of diminishing income and wealth production. As the vast inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth deny the provision of basic living necessities to tens of millions and circumscribe opportunity for most Americans, social instability and political division and violence escalate. In response, an authoritarian regime consolidates its power around armed force to repress those protesting its anti-democratic policies. Its armed repression inevitably leads to bloodshed.

The pro-democracy citizenry must organize around a political vision that emphasizes several political projects: a just, progressive taxation system; a guaranteed household income; universal healthcare; quality public education; free preschool education; and scientific and technological initiatives for a sustainable economy. These political goals stand in stark contrast to an authoritarian regime that advances the interests of the one percent. They offer a view of the future that is constructive and inspirational, one that generates broad social justice and appeals to the vast majority of Americans.