At Least 146 Killed or Disappeared for 'Defending Life Itself' Last Year

"It is critical that governments and companies turn the tide to uphold defenders’ rights and protect them rather than persecute them," said the lead author of the new Global Witness report.

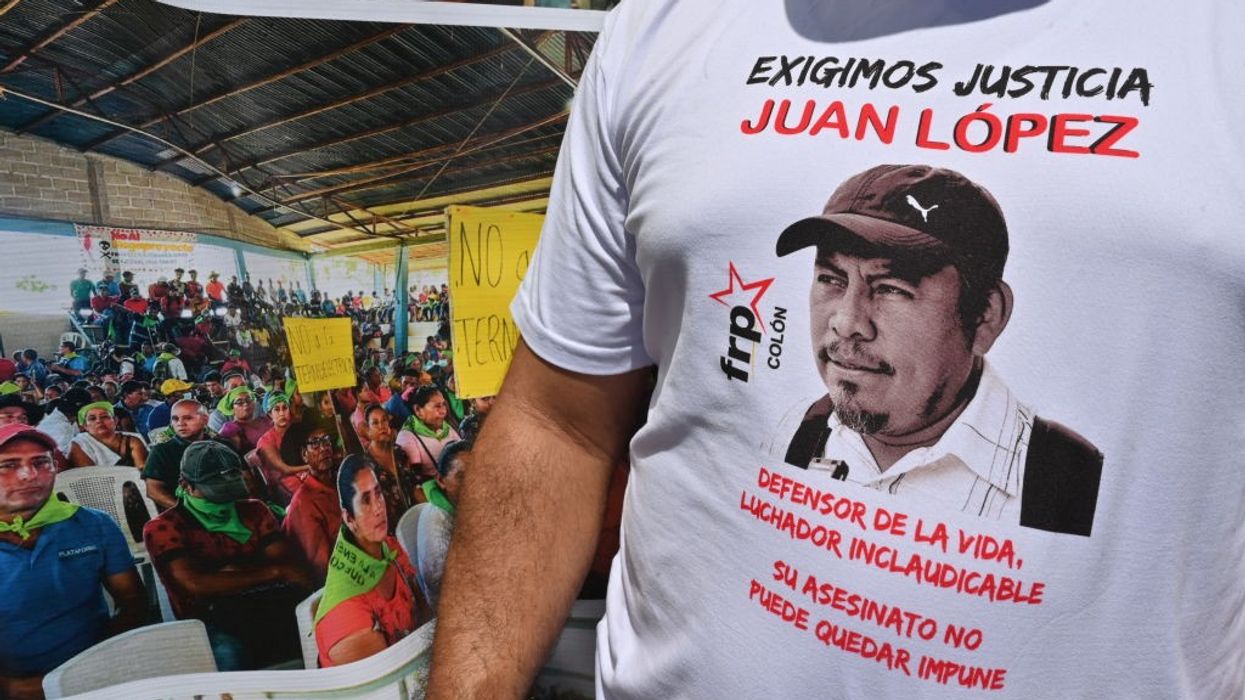

At least 142 people were killed and four were confirmed missing last year for "bravely speaking out or taking action to defend their rights to land and a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment," according to an annual Global Witness report published Wednesday.

"Year after year, land and environmental defenders—those protecting our forests, rivers, and lands across the world—continue to be met with unspeakable violence," said Laura Furones, the report's lead author, in a statement. "They are being hunted, harassed, and killed—not for breaking laws, but for defending life itself."

"Standing up to injustice should never be a death sentence," Furones declared. "It is critical that governments and companies turn the tide to uphold defenders' rights and protect them rather than persecute them. We desperately need defenders to keep our planet safe. If we turn our backs on them, we forfeit our future."

The report, Roots of Resistance, begins by listing the activists who were murdered or disappeared for six months or more in 2024. It also says: "We acknowledge that the names of many defenders who were killed or disappeared last year may be missing, and we may never know how many more gave their lives to protect our planet. We honor their work too."

The most dangerous country for environmental defenders, by far, was Colombia, with 48 deaths. Jani Silva, a defender there living under state protection, said that "as this report shows, the vast majority of defenders under attack are not defenders by choice—including myself. We are defenders because our homes, land, communities, and lives are under threat. So much more must be done to ensure communities have rights and that those who stand up for them are protected."

Colombia was followed by Guatemala (20), Mexico (18), Brazil (12), the Philippines (7), Honduras (5), Indonesia (5), Nicaragua (4), Peru (4), the Democratic Republic of Congo (4), Ecuador (3), and Liberia (3). There was one confirmed killing each in Russia, India, Venezuela, Argentina, Madagascar, Turkey, Cameroon, Cambodia, and the Dominican Republic. The four disappearances were in Chile, Honduras, Mexico, and the Philippines.

"This brings the total figure to 2,253 since we started reporting on attacks in 2012. This appalling statistic illustrates the persistent nature of violence against defenders," the report states. It stresses that while the new figure is lower than the 196 cases in 2023, "this does not indicate that the situation for defenders is improving."

The report notes that "120 (82%) of all the cases we documented in 2024 took place in Latin America," while 16 killings occurred in Asia and nine were in Africa. It emphasizes that "underreporting remains an issue globally, particularly across Asia and Africa. Obstacles to verify suspected violations also present a problem, particularly documenting cases in active conflict zones."

A third of all land and environmental defenders killed or disappeared last year were Indigenous. The deadliest industry was mining and extractives, at 29, followed by logging (8), agribusiness (4), roads and infrastructure (2), hydropower (1), and poaching.

In addition to detailing who was killed or disappeared, what they fought for, and how "the current system is failing defenders," the report offers recommendations for "how states and businesses can better protect defenders."

Currently, said Global Witness project lead Rachel Cox, "states across the world are weaponizing their legal systems to silence those speaking out in defense of our planet."

"Amid rampant resource use, escalating environmental pressure, and a rapidly closing window to limit warming to 1.5°C, they are treating land and environmental defenders like they are a major inconvenience instead of canaries in a coal mine about to explode," she continued.

"Meanwhile, governments are failing to hold those responsible for defender attacks to account—spurring the cycle of killings with little consequence," she added. "World leaders must acknowledge the role they must play in ending this once and for all."

The recommendation section specifically points to the upcoming United Nations climate summit, COP30, in Belém, Brazil, "a city amid one of the world's most biodiverse regions—and one of the most dangerous countries to be a land and the environment defender."

"The protection and meaningful participation of land and environmental defenders at COP30 and beyond is an essential element of the fight against climate change," the document says. "It must become a core principle of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Convention on Biological Diversity process."