Seabird Conservation Is an Emotional Roller Coaster, But It's Worth the Ride

Members of a five-person crew who spend their summers tending to puffins, terns, and other sea birds on Seal Island, Maine, share what it's like to do this essential work despite a changing climate and a hostile administration.

After contorting under boulders for puffin chicks, chasing skittish tern chicks in the weeds, and sitting as stone-silent sentinels in bird blinds to observe feeding and behavior, the five-person research crew on Seal Island relaxed in their work cabin in the orange and purple sunset glow. Their conversation on a mid-July evening wafted into waves of joy, angst, anger, and gratitude.

The emotional highs and lows of that conversation were something Coco Faber, Camilla Dopulos, Liv Ridley, Mark Price, and Jack Eibel wanted the world to hear and feel, from 21 miles out to sea from the coast of Maine.

The Joy

A puffin catches a fish. (Photo by Derrick Jackson)

The joys were obvious. One was that, despite the Gulf of Maine overall being one of the fastest-warming bodies of ocean on Earth, it was a near-spectacular summer for puffins on Seal Island, a place legendary in the world of conservation. A part of the National Wildlife Refuge System and managed by the Audubon Seabird Institute, the island is part of the world’s first successful restoration of seabirds where humans killed them off.

Atlantic puffins were wiped out here and across several islands in Maine by the 1880s as coastal fishing and farming communities hunted them for their meat and eggs. Seal Island, a mile long, had hosted the then-largest-known puffin colony in the Gulf of Maine.

In my visit in mid-July, I often had between 100 and 200 puffins stretching across my view from my bird blind.

In the 1970s, Steve Kress, then an Audubon bird instructor in his late 20s, launched what became known as Project Puffin (and now known as the Seabird Institute). He brought hundreds of puffin chicks down from Newfoundland to hand raise on Eastern Egg Rock, a tiny 7-acre island, 6 miles off Pemaquid Point. Puffins began breeding anew on that island in 1981 and set a record 188 breeding pairs in 2019.

Kress repeated the experiment with hundreds more chicks on Seal Island, much farther out to the northeast. Puffins began breeding once more here in 1992. Last year, Faber and her team counted a record 672 active burrows.

“I’m very confident that there are more burrows,” said Faber, 31, who is the island supervisor and in her tenth summer with the Seabird Institute. “There are so many more that we have found since and burrows we might have missed because the chick fledged before we could get to them.”

You could not doubt her. In my visit in mid-July, I often had between 100 and 200 puffins stretching across my view from my bird blind. Puffin parents brought in a steady stream of juicy haddock, nice long sand lance, and even occasional herring to feed their chicks. Faber reported to fellow researchers on other islands that many Seal puffin chicks were “big and healthy.” Alcid cousins of puffins, black guillemots and razorbills, had their highest chick productivity ever.

If only all the birds the crew managed were so lucky.

The Angst

A tern delivers a fine meal of sand lance to a chick. (Photo by Derrick Jackson)

The same ocean that was a sea of plenty for puffins was more of paucity for Arctic, common, and roseate terns. They are species also restored across the Gulf of Maine by the Seabird Institute and the US Fish and Wildlife Service after decades of absence. They screech and dive to protect their chicks on the ground from gulls. By coincidence, that vigilance also offers protective cover for puffins down below.

Many species of terns were among the estimated 300 million birds slaughtered in the late 19th and early 20th century for feathers to adorn women’s hats. Public outcry led to the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. The protections helped the tern population in Maine briefly rebound until the 1930s.

But the overall ecosystem was so upset by the prior massacres that terns were crowded off many islands by herring gulls and great black-backed gulls. Both species of gulls were also decimated in the feather trade. But being omnivores that feast both on bird chicks and garbage from landfills and fishing waste, their populations recovered much faster than terns and puffins, which feed solely on fish. Terns left Seal Island by mid-century, and the island became even more inhospitable as it became a Navy bombing range from the 1940s to the 1960s.

With the help of decoys, recorded tern calls, and gull control, 16 pairs of Arctic and 1 pair of common terns nested once more on Seal Island in 1989. By 2011, the colony grew to 3,038 pairs.

“Our observations of the terns show us how the impacts of climate change can cascade in interesting and often horrifying ways,” Faber said.

But the colony has shrunk steadily and dramatically since then. This summer, the island crew counted only 1,203 Arctic and common tern nests. That was the lowest combined census count since 1995.

The reasons are likely many. The last decade and a half has seen the warmest water temperatures ever recorded in the Gulf of Maine. When temperatures are particularly high, species of fish that terns snatch on the surface to feed chicks often flee too deep to be caught. Unlike puffins, razorbills, and guillemots, which can dive to hunt a variety of fish, terns feed only at the surface.

Then add the fact that terns are only in the Gulf of Maine from May to August. Common terns migrate as far south as Chile and Argentina. Arctic terns are the world’s longest-traveling migratory bird, breeding at the top of the Northern Hemisphere and wintering off Antarctica. Some Arctic terns hatched in Maine veer around South Africa into the Indian Ocean before joining other terns in the Weddell Sea.

Between their fall and spring migrations and the incessant flying for food, they can cover 55,000 miles in one year. In a lifetime, an Arctic tern, which can live past 30, could have made three round trips to the moon.

In its journey, a single tern can face a myriad of uncertainties from sea ice loss, overfishing, pollution, and coastal development. In recent years, many Arctic terns have returned to Seal Island in poor body condition. An international team of researchers found in a 2023 study that what might seem “minor changes” in conditions along the migration routes of Arctic terns may sum up to an effect that proves to be “greater than the parts.”

The Seal Island crew said they are already witnessing the compound effects. This year, as in several recent years, many Arctic terns arrived from spring migration in poor body condition. After an early tease of herring and hake, most of the food being brought to chicks by summer’s end was tiny crustaceans. In my blind stints, parent terns landed before me with a single krill, a dragonfly, a moth, or a tiny pufferfish.

And it could be even worse. This summer was relatively dry, but in years of both poor food supply and incessant rains, crews have told me there is no more helpless feeling than being holed up in their cabin and tents while weakened chicks are being soaked into fatal hypothermia.

It feels harder to get people to care when the nation is currently under a White House that is trying to weaken or gut the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and firing thousands of federal staff involved with conservation.

“Our observations of the terns show us how the impacts of climate change can cascade in interesting and often horrifying ways,” Faber said. She said low weight adults may lay smaller clutches of eggs, abandon nests early in the season or flush more easily from nests when gulls swoop down to try to eat eggs or chicks. Parents that get lucky and return to the island with a juicy fish for a chick are mugged in midair by other terns and gulls, often dropping a fish that no chick gets to eat.

Poor fish availability of course leads to poor growth of the chicks that survive and less chance of surviving during their first migration. “If the fish don’t last for the entire season, tern chicks that started out fat and grew quickly can still starve to death,” Faber said. “Adults are also more aggressive to neighboring chicks, sometimes to the point of killing them and chicks will pile onto each other if an adult does land with a fish.”

It makes it all the more celebratory when luckier chicks do survive and start flying around the island. The first sight of a chick fledging is often a cause for cheering and clapping. “I call it Tern TV,” said Dopulos, 24. “Sometimes it’s comedy, sometimes it’s tragedy.”

Price, 19, noting how hard parent terns work to find food for chicks, even to the point of bringing insects back, said, “They’re such fierce fighters. The funny thing is, with puffins, we don’t ever see most of the chicks under the rocks. We see the tern chicks every single day. It feels more personal.”

Ridley, 27, added, “To think that they go from little fluff balls to trying to fly in three weeks and then fly to Antarctica never stops being amazing.”

The crew said if people, who pack boat tours by the thousands each summer to admire puffins with their clownish orange, yellow and black bills and tuxedo-like plumage, really cared about that bird, they would also care about the challenges for terns.

Fortunately, terns did much better elsewhere in the Gulf of Maine as several islands racked up record numbers of common terns in 2022. But with seabirds in severe global decline, nothing can be taken for granted. Neither Arctic terns nor common terns are federally endangered, but Arctic terns are a threatened species in Maine as they “still far below historic levels.” Common terns are in decline in the Great Lakes.

Faber said it was “morally repugnant” to her that in a world where humans consider themselves the center of existence, that a “cute” species like puffins merits attention, while so many other creatures, like terns, are afterthoughts or ignored altogether. “I love the puffins,” she said. “They are the umbrella species for conservation. But terns are the umbrella species for puffins.”

The Anger

Puffins, once gone for nearly a century from several islands in Maine, are now a prime tourist draw. (Photo by Derrick Jackson)

And this is where the crew’s angst simmers into anger.

It feels harder to get people to care when the nation is currently under a White House that is trying to weaken or gut the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and firing thousands of federal staff involved with conservation.

“We get to escape from the darkest parts of the world,” she said. “I feel extra lucky to be here at this moment.”

The effects of the actions in DC earlier this year were acutely felt within the crew this summer. Dopulos had a job lined up this summer with the National Park Service. But it was cut by the Trump administration. She has several friends who lost their jobs in a service that has lost nearly a quarter of its permanent employees and left thousands of seasonal jobs unfilled.

“Some of them are still doing what they were doing to protect wildlife and resources, but as volunteers,” Dopulos said. “And they’re joining protests at the same time. They’re so passionate about what they do that they’re not going to let government get in the way. It’s a way of saying ‘We still persist.’”

The Gratitude

Holding a puffin is the Seal Island crew of (from left to right): Supervisor Coco Faber, Camilla Dopulos, Jack Eibel, Mark Price, and Liv Ridley. (Photo by Derrick Jackson)

For Dopulos and the crew, talking about persistence led back to a more joyful place. Even with the oft-dour drama of terns, they all said they were grateful for the privilege of living for three months of the year out of tents, tending to such an historic sanctuary.

“It’s my favorite place in the world,” said Ridley, who winters as a line cook in Idaho. “You get to live in a place that is not human dominated. Everywhere else, we manipulate the world. People think that the human way is the only way, but living in a society of seabirds proves to me daily that it isn’t. I feel lucky to have that perspective.”

Faber said Seal Island has become her own sanctuary. “We get to escape from the darkest parts of the world,” she said. “I feel extra lucky to be here at this moment.”

Feeling just as lucky was Steve Kress, who came out to Seal Island for a day while I was there. He and I have coauthored two books on his seabird restorations. Being much more remote than Eastern Egg Rock, Seal Island has never come close to receiving the press the pioneering island still receives. But while Egg Rock proved puffins could be brought back, Kress said Seal’s restoration, with three times more puffins, “makes me see the grand possibilities for restoration where there is such abundant, quality nesting habitat."

“When puffins first nested at Seal Island, we weren’t as overwhelmed and relieved as when the first pairs reclaimed Egg Rock. But the fact that similar methods led to the same outcome proved that we were on to something very important. It’s encouraging to find that given enough time, persistence, and patience, successful restoration projects can become the norm.”

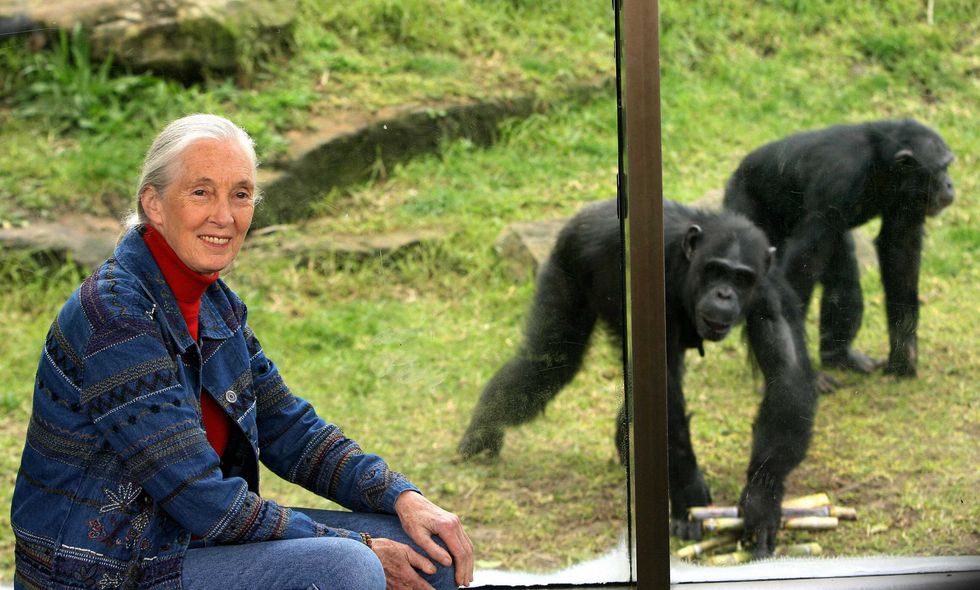

British primatologist Jane Goodall visits a chimp rescue center on June 9, 2018 in Entebbe,

British primatologist Jane Goodall visits a chimp rescue center on June 9, 2018 in Entebbe,  Primatologist Jane Goodall visits the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia on July 14, 2006. (Photo by Greg Wood/AFP via Getty Images)

Primatologist Jane Goodall visits the Taronga Zoo in Sydney, Australia on July 14, 2006. (Photo by Greg Wood/AFP via Getty Images)