SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

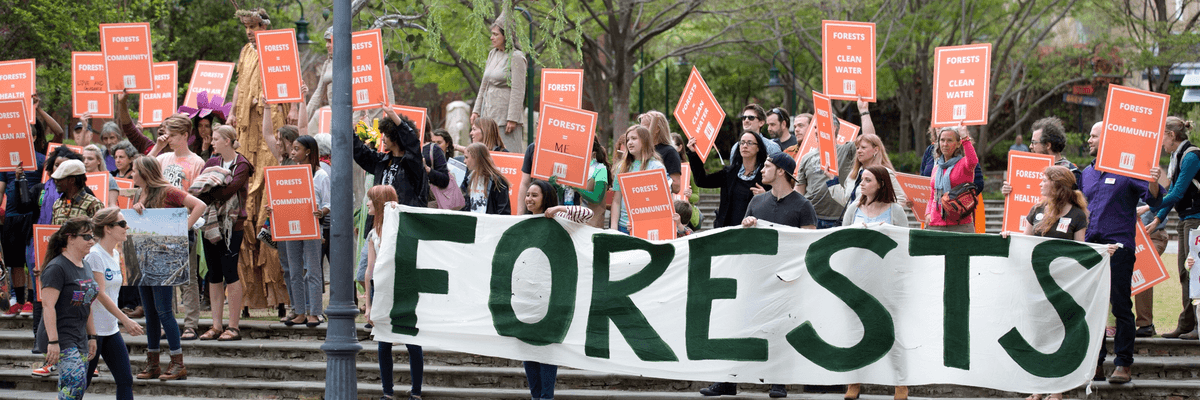

The Dogwood Alliance holds a demonstration in support of forests.

Working together, we can continue to advance a better, more sustainable vision for the South.

May is one of my favorite months to go walking through the forests near my home in Cedar Mountain, North Carolina. Up here, near the mountainous border between the Carolinas, the air smells sweet and clean this time of the year, filtered by the bounty of trees. I’ve gotten to know some of them like neighbors: the cucumber magnolias, maples, sourwoods, and, of course, dogwoods.

I am a lifelong lover of forests. I am also the executive director of the Dogwood Alliance, an environmental organization dedicated to preserving Southeastern forests. As such, I make sure to pay attention to the forests and the trees.

Lately, when I visit the forests, I see scars. I see the smoldering scars of the recent fires that sent my husband and me into a panicked evacuation. Or, I see the giant holes where trees used to be before Hurricane Helene, which devastated the area and kept me stranded in New York City for days unable to get in touch with my husband or my daughter. Ironically, I was at the annual gathering known as Climate Week as everyone learned that the Asheville area is not a climate haven. Nowhere really is. My neck of the woods is beautiful, but not invincible.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Still, when it comes to climate change, our forests are our best friends and biggest protectors. They can block the wind and absorb the water before it inundates communities. They’re also among the oldest and best tools in the toolbox when it comes to climate change because nothing—and I mean nothing—stores carbon like a good, old-fashioned tree.

And as destructive as the hurricane and the fires were, the biggest threat to our forests remains the logging industry. The rate of logging in our Southern U.S. forests is four times higher than that of the South American rainforests. Despite claims to the contrary, the logging industry is the biggest tree-killer in the nation.

The wood-pellet biomass industry is a major culprit. Over the last 10 years, our region has become the largest wood-pellet exporter in the entire world. Companies receive massive subsidies to chop our forests into wood pellets that are then shipped overseas to be burned for electricity. This process is a major waste of taxpayer dollars and produces more carbon emissions than coal.

And it seems that regardless of who is in charge at the state or federal level, they consistently fail to protect forests. Most recently, President Donald Trump signed executive orders that threaten to turbocharge logging and wood production while subverting cornerstone legal protections such as the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. The truth is that policies that increase logging and wood production will only make communities like mine even more vulnerable to climate impacts, while decreasing the likelihood of recovery. The Trump administration's efforts to ramp up logging and close environmental justice offices are especially troublesome given the disproportionate impact that the forestry industry has on disadvantaged communities.

It can be an alarming picture to look at, especially when I think about the communities that will be harmed the most: low-income communities of color. But, I’m not new to this movement. I’ve seen again and again, those same communities rise up and fight off some of the biggest multinational corporations on the planet and hold our elected officials’ feet to the fire.

We’ve successfully clawed back subsidies for the biomass industry, slowing the growth of wood-pellet plants, and sounded the alarm when these facilities violated important pollution limits. They’ve had to pay millions of dollars in fines, shut down plants, and scrap plans for expansion. This is what gives me hope for the people and forests of the South.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Just last month, Dogwood Alliance’s community partners in Gloster, Mississippi scored a major victory. The community exerted huge pressure on the state’s Department of Environmental Quality to deny a permit to expand wood-pellet production for Drax—one of the most powerful multinational biomass corporations—and won! This means that the town’s residents will not have to face increased air pollution, noise pollution, traffic, and the greater mutilation of their bucolic landscape. If Gloster, a town of less than 1,000 people, can beat a megacorporation, I know we can stand up to the Trump administration and continue to advance a better, more sustainable vision for the South.

Through my work, I have the absolute privilege of partnering with some of the most inspiring leaders in the environmental justice movement. For example, we are partnering with Reverend Leo Woodberry, a pastor in South Carolina, to create a community forest on the land where his ancestors were once enslaved. With the support of community-focused donors, soon the Britton’s Neck Community Conservation Forest will be full of hiking trails, camp sites, and an ecolodge for locals and tourists from around the world to enjoy. This rise in outdoor recreation and (literal) foot traffic will create a badly needed economic rejuvenation for the local community, thus turning standing trees into gold. After all, outdoor recreation creates five times more jobs than the forestry industry.

This is not an isolated story. Four years ago this month, the Pee Dee Indian Tribe cut the ribbon on their educational center and 100-acre community forest in McColl, South Carolina as part of their effort to create a regenerative economy that prioritizes ecological harmony. All across the South, people are protecting the forests that protect them through a new community-led Justice Conservation initiative, which prioritizes forest protection in the communities on the front lines of our nation's most heavily logged areas.

The other day, when I went for my walk, I noticed that the scars are starting to give way to shoots of new growth. This is the time of year when the trees come alive, lighting the forest with purple and pink and white blossoms. That, to me, is hope. That, to me, is a miracle.

Right now, it feels like the whole world is on edge, bracing for the next major weather event. I know how helpless it can feel to watch the communities you love experience severe damage, I’ve lived it. But we are our own best hope. Just like the trees in a forest, we’re stronger together. Whether you live here in the South or across the country, I invite you to join us in protecting our forests and supporting the types of projects we’re spearheading through the Justice Conservation initiative.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

May is one of my favorite months to go walking through the forests near my home in Cedar Mountain, North Carolina. Up here, near the mountainous border between the Carolinas, the air smells sweet and clean this time of the year, filtered by the bounty of trees. I’ve gotten to know some of them like neighbors: the cucumber magnolias, maples, sourwoods, and, of course, dogwoods.

I am a lifelong lover of forests. I am also the executive director of the Dogwood Alliance, an environmental organization dedicated to preserving Southeastern forests. As such, I make sure to pay attention to the forests and the trees.

Lately, when I visit the forests, I see scars. I see the smoldering scars of the recent fires that sent my husband and me into a panicked evacuation. Or, I see the giant holes where trees used to be before Hurricane Helene, which devastated the area and kept me stranded in New York City for days unable to get in touch with my husband or my daughter. Ironically, I was at the annual gathering known as Climate Week as everyone learned that the Asheville area is not a climate haven. Nowhere really is. My neck of the woods is beautiful, but not invincible.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Still, when it comes to climate change, our forests are our best friends and biggest protectors. They can block the wind and absorb the water before it inundates communities. They’re also among the oldest and best tools in the toolbox when it comes to climate change because nothing—and I mean nothing—stores carbon like a good, old-fashioned tree.

And as destructive as the hurricane and the fires were, the biggest threat to our forests remains the logging industry. The rate of logging in our Southern U.S. forests is four times higher than that of the South American rainforests. Despite claims to the contrary, the logging industry is the biggest tree-killer in the nation.

The wood-pellet biomass industry is a major culprit. Over the last 10 years, our region has become the largest wood-pellet exporter in the entire world. Companies receive massive subsidies to chop our forests into wood pellets that are then shipped overseas to be burned for electricity. This process is a major waste of taxpayer dollars and produces more carbon emissions than coal.

And it seems that regardless of who is in charge at the state or federal level, they consistently fail to protect forests. Most recently, President Donald Trump signed executive orders that threaten to turbocharge logging and wood production while subverting cornerstone legal protections such as the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. The truth is that policies that increase logging and wood production will only make communities like mine even more vulnerable to climate impacts, while decreasing the likelihood of recovery. The Trump administration's efforts to ramp up logging and close environmental justice offices are especially troublesome given the disproportionate impact that the forestry industry has on disadvantaged communities.

It can be an alarming picture to look at, especially when I think about the communities that will be harmed the most: low-income communities of color. But, I’m not new to this movement. I’ve seen again and again, those same communities rise up and fight off some of the biggest multinational corporations on the planet and hold our elected officials’ feet to the fire.

We’ve successfully clawed back subsidies for the biomass industry, slowing the growth of wood-pellet plants, and sounded the alarm when these facilities violated important pollution limits. They’ve had to pay millions of dollars in fines, shut down plants, and scrap plans for expansion. This is what gives me hope for the people and forests of the South.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Just last month, Dogwood Alliance’s community partners in Gloster, Mississippi scored a major victory. The community exerted huge pressure on the state’s Department of Environmental Quality to deny a permit to expand wood-pellet production for Drax—one of the most powerful multinational biomass corporations—and won! This means that the town’s residents will not have to face increased air pollution, noise pollution, traffic, and the greater mutilation of their bucolic landscape. If Gloster, a town of less than 1,000 people, can beat a megacorporation, I know we can stand up to the Trump administration and continue to advance a better, more sustainable vision for the South.

Through my work, I have the absolute privilege of partnering with some of the most inspiring leaders in the environmental justice movement. For example, we are partnering with Reverend Leo Woodberry, a pastor in South Carolina, to create a community forest on the land where his ancestors were once enslaved. With the support of community-focused donors, soon the Britton’s Neck Community Conservation Forest will be full of hiking trails, camp sites, and an ecolodge for locals and tourists from around the world to enjoy. This rise in outdoor recreation and (literal) foot traffic will create a badly needed economic rejuvenation for the local community, thus turning standing trees into gold. After all, outdoor recreation creates five times more jobs than the forestry industry.

This is not an isolated story. Four years ago this month, the Pee Dee Indian Tribe cut the ribbon on their educational center and 100-acre community forest in McColl, South Carolina as part of their effort to create a regenerative economy that prioritizes ecological harmony. All across the South, people are protecting the forests that protect them through a new community-led Justice Conservation initiative, which prioritizes forest protection in the communities on the front lines of our nation's most heavily logged areas.

The other day, when I went for my walk, I noticed that the scars are starting to give way to shoots of new growth. This is the time of year when the trees come alive, lighting the forest with purple and pink and white blossoms. That, to me, is hope. That, to me, is a miracle.

Right now, it feels like the whole world is on edge, bracing for the next major weather event. I know how helpless it can feel to watch the communities you love experience severe damage, I’ve lived it. But we are our own best hope. Just like the trees in a forest, we’re stronger together. Whether you live here in the South or across the country, I invite you to join us in protecting our forests and supporting the types of projects we’re spearheading through the Justice Conservation initiative.

May is one of my favorite months to go walking through the forests near my home in Cedar Mountain, North Carolina. Up here, near the mountainous border between the Carolinas, the air smells sweet and clean this time of the year, filtered by the bounty of trees. I’ve gotten to know some of them like neighbors: the cucumber magnolias, maples, sourwoods, and, of course, dogwoods.

I am a lifelong lover of forests. I am also the executive director of the Dogwood Alliance, an environmental organization dedicated to preserving Southeastern forests. As such, I make sure to pay attention to the forests and the trees.

Lately, when I visit the forests, I see scars. I see the smoldering scars of the recent fires that sent my husband and me into a panicked evacuation. Or, I see the giant holes where trees used to be before Hurricane Helene, which devastated the area and kept me stranded in New York City for days unable to get in touch with my husband or my daughter. Ironically, I was at the annual gathering known as Climate Week as everyone learned that the Asheville area is not a climate haven. Nowhere really is. My neck of the woods is beautiful, but not invincible.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Still, when it comes to climate change, our forests are our best friends and biggest protectors. They can block the wind and absorb the water before it inundates communities. They’re also among the oldest and best tools in the toolbox when it comes to climate change because nothing—and I mean nothing—stores carbon like a good, old-fashioned tree.

And as destructive as the hurricane and the fires were, the biggest threat to our forests remains the logging industry. The rate of logging in our Southern U.S. forests is four times higher than that of the South American rainforests. Despite claims to the contrary, the logging industry is the biggest tree-killer in the nation.

The wood-pellet biomass industry is a major culprit. Over the last 10 years, our region has become the largest wood-pellet exporter in the entire world. Companies receive massive subsidies to chop our forests into wood pellets that are then shipped overseas to be burned for electricity. This process is a major waste of taxpayer dollars and produces more carbon emissions than coal.

And it seems that regardless of who is in charge at the state or federal level, they consistently fail to protect forests. Most recently, President Donald Trump signed executive orders that threaten to turbocharge logging and wood production while subverting cornerstone legal protections such as the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. The truth is that policies that increase logging and wood production will only make communities like mine even more vulnerable to climate impacts, while decreasing the likelihood of recovery. The Trump administration's efforts to ramp up logging and close environmental justice offices are especially troublesome given the disproportionate impact that the forestry industry has on disadvantaged communities.

It can be an alarming picture to look at, especially when I think about the communities that will be harmed the most: low-income communities of color. But, I’m not new to this movement. I’ve seen again and again, those same communities rise up and fight off some of the biggest multinational corporations on the planet and hold our elected officials’ feet to the fire.

We’ve successfully clawed back subsidies for the biomass industry, slowing the growth of wood-pellet plants, and sounded the alarm when these facilities violated important pollution limits. They’ve had to pay millions of dollars in fines, shut down plants, and scrap plans for expansion. This is what gives me hope for the people and forests of the South.

We’re not only fighting what’s bad but also working toward what’s good.

Just last month, Dogwood Alliance’s community partners in Gloster, Mississippi scored a major victory. The community exerted huge pressure on the state’s Department of Environmental Quality to deny a permit to expand wood-pellet production for Drax—one of the most powerful multinational biomass corporations—and won! This means that the town’s residents will not have to face increased air pollution, noise pollution, traffic, and the greater mutilation of their bucolic landscape. If Gloster, a town of less than 1,000 people, can beat a megacorporation, I know we can stand up to the Trump administration and continue to advance a better, more sustainable vision for the South.

Through my work, I have the absolute privilege of partnering with some of the most inspiring leaders in the environmental justice movement. For example, we are partnering with Reverend Leo Woodberry, a pastor in South Carolina, to create a community forest on the land where his ancestors were once enslaved. With the support of community-focused donors, soon the Britton’s Neck Community Conservation Forest will be full of hiking trails, camp sites, and an ecolodge for locals and tourists from around the world to enjoy. This rise in outdoor recreation and (literal) foot traffic will create a badly needed economic rejuvenation for the local community, thus turning standing trees into gold. After all, outdoor recreation creates five times more jobs than the forestry industry.

This is not an isolated story. Four years ago this month, the Pee Dee Indian Tribe cut the ribbon on their educational center and 100-acre community forest in McColl, South Carolina as part of their effort to create a regenerative economy that prioritizes ecological harmony. All across the South, people are protecting the forests that protect them through a new community-led Justice Conservation initiative, which prioritizes forest protection in the communities on the front lines of our nation's most heavily logged areas.

The other day, when I went for my walk, I noticed that the scars are starting to give way to shoots of new growth. This is the time of year when the trees come alive, lighting the forest with purple and pink and white blossoms. That, to me, is hope. That, to me, is a miracle.

Right now, it feels like the whole world is on edge, bracing for the next major weather event. I know how helpless it can feel to watch the communities you love experience severe damage, I’ve lived it. But we are our own best hope. Just like the trees in a forest, we’re stronger together. Whether you live here in the South or across the country, I invite you to join us in protecting our forests and supporting the types of projects we’re spearheading through the Justice Conservation initiative.