Whistleblower: Kash Patel's Use of FBI Jets for Personal Travel Delayed Murder Probe

"The FBI cannot afford to have its resources further stretched by a director who views its staff and aircraft as a means to support his jet-setting lifestyle."

A whistleblower is claiming that FBI Director Kash Patel's frequent use of one of the agency's two jets has led to the delay of a high-profile murder probe.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) on Tuesday revealed he had received new whistleblower disclosures related to his investigations into Patel's use of FBI aircraft for personal travel, and he said they showed Patel's decisions regarding the use of FBI planes had delayed investigations not only into the murder of right-wing activist Charlie Kirk but also the November 2025 mass shooting at Brown University.

In the case of Kirk, Durbin said that the FBI shooting reconstruction team's deployment to Utah "was delayed by at least a day because of a bureau plane and pilot shortage caused by the director's personal flights."

Durbin said that he also received information showing how Patel bungled the aftermath of the Brown shooting by putting the FBI's Hostage Rescue Team (HRT) on standby to respond to the incident.

"The director’s decision caused immediate confusion," Durbin said, "because that order was not communicated to HRT; it upended the responsibility typically assigned to the local field office closest to the incident in question—in this case Boston or New York City—to provide immediate support; and it froze the aircraft’s usage by any other FBI team until the director removed the hold."

Durbin then said that the whistleblower described how his team "had to drive from Quantico, Virginia to Providence, Rhode Island overnight during a winter storm to reach the scene by 9:00 am the following morning to immediately process evidence."

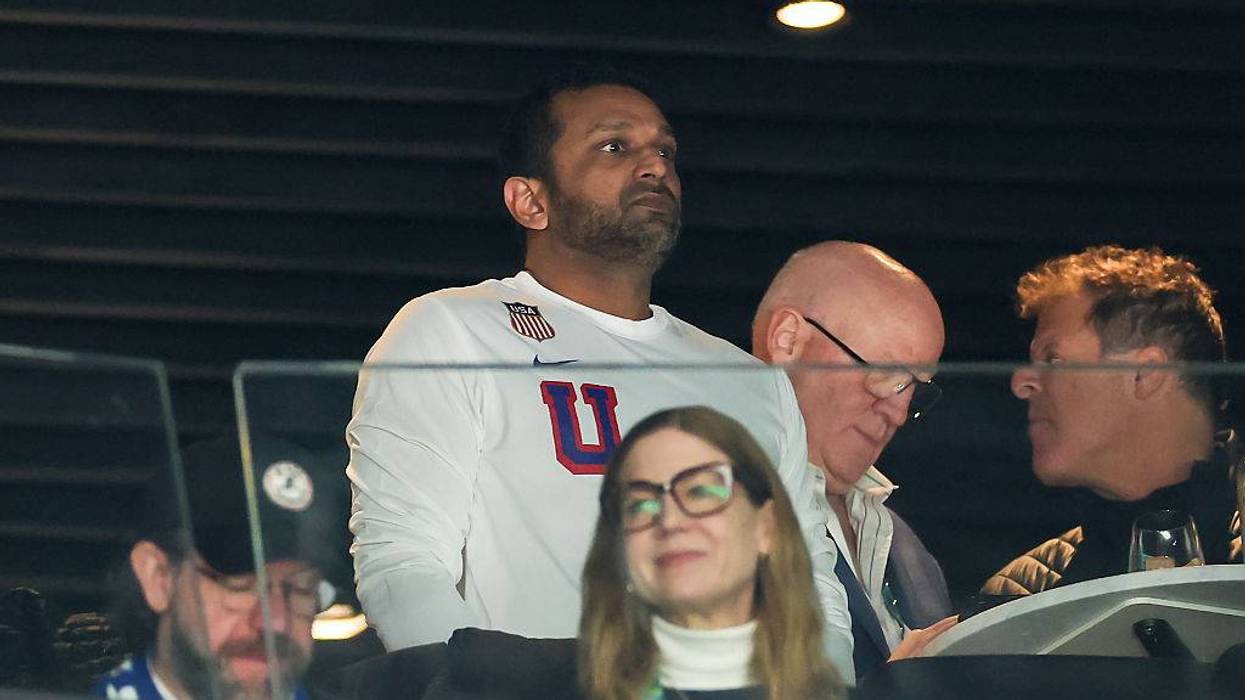

Durbin noted he received this information shortly after Patel was seen chugging down a beer in the locker room of the gold medal-winning US men's Olympic hockey team on Sunday, after the director once again used an FBI plane to fly to Milan, Italy.

The Democratic senator said that Patel's trip to Italy could have seriously hampered the FBI's ability to investigate what may have been an assassination attempt on President Donald Trump.

"It also cannot be ignored that the director’s latest personal jaunt occurred on the same weekend an armed intruder attempted to breach President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence," Durbin explained. "The man was allegedly carrying a gas can and a shotgun, and he was killed on the scene by law enforcement."

Durbin concluded by saying that "the FBI cannot afford to have its resources further stretched by a director who views its staff and aircraft as a means to support his jet-setting lifestyle."

MS NOW reported that an FBI spokesperson has "disputed" the whistleblower's claims that Patel's decisions had caused delays to investigations, but added that they need to "check into the matter more deeply to gather information."