SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

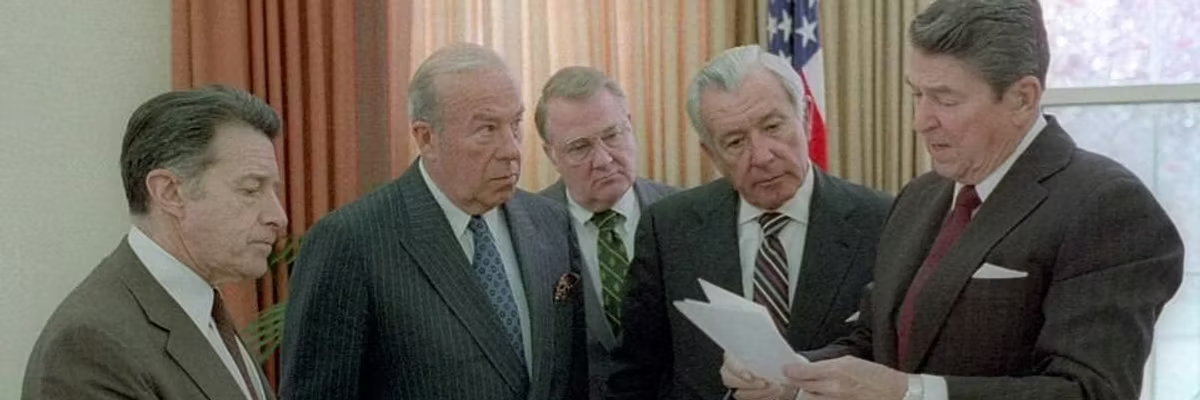

President Ronald Reagan discusses his remarks on the Iran-Contra affair with Caspar Weinberger, George Shultz, Ed Meese, and Don Regan in the Oval Office on November 25, 1986.

For decades, the most powerful state actors facilitating and protecting narcotics trafficking have not been Washington’s adversaries but Washington itself.

Every accusation is a confession. This is clearly true of the Trump administration’s insistence that Venezuela operates as a “narco-state,” exporting terrorism to the US via fentanyl, now labeled as a “weapon of mass destruction.” The charge is not only false, given that virtually no fentanyl enters the country from Venezuela, but transparently political and pretextual.

This hypocrisy was made unmistakable with President Donald Trump’s recent pardon of former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was convicted in 2024 in a US federal court on drug trafficking charges. Hernández presided over a regime long treated as a strategic ally within Washington’s regional security architecture, a reminder that the label of “narco-state” is applied not according to fact but according to the shifting imperatives of US imperial power.

This accusation collapses further when placed in broader historical context. For decades, the most powerful state actors facilitating and protecting narcotics trafficking have not been Washington’s adversaries but Washington itself. Throughout the Cold War and the so-called War on Drugs, the United States, above all through the CIA, repeatedly subordinated drug enforcement to geopolitical priorities, enabling narco-networks so long as they advanced perceived US interests.

These dynamics became especially pronounced in the 1980s, with disastrous consequences both at home and abroad. The decade marked an intensification of the Cold War under Ronald Reagan. His administration insisted that communist “advances” could not only be contained but rolled back. Upon taking office, Reagan launched his promised global offensive, intervening wherever alleged Soviet influence appeared. Turning a blind eye to drug trafficking became a central feature of this crusade, as anti-communism consistently took precedence over anti-narcotics efforts.

Reagan’s rise followed a brief but meaningful thaw. In the wake of Watergate and the Vietnam War, Americans’ faith in political institutions had been profoundly shaken. Years of economic stagnation, inflation, and the reverberations of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo convinced many that the postwar promise of endless upward mobility, the ideological core of the American dream, was collapsing.

It also became impossible to ignore that the US was not only failing to deliver on its economic promise but had also long abandoned the democratic values it claimed to champion. In 1975, the Church Committee laid bare what much of the Global South had known for decades: The United States had been operating as a global anti-democratic force, orchestrating coups and assassinations, sabotaging leftist movements (at home and abroad), and imposing political outcomes that served the interests of American capital rather than the aspirations of people around the world.

Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Then, in 1977, came Jimmy Carter. Carter promised a new foreign policy rooted not in reflexive anti-communism but a commitment to human rights. In doing so, he broke, at least in his rhetoric, with decades of bipartisan Cold War orthodoxy. For the first time, a president openly challenged the axiomatic belief that every leftist movement was a Kremlin proxy that demanded immediate US intervention.

As Carter put it, “We are now free of that inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear,” acknowledging that “for too many years, we’ve been willing to adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs.” Washington, he admitted, had “fought fire with fire, never thinking that fire is better quenched with water,” a strategy that had ultimately backfired.

Carter would also come to critique not only the misguided zealotry of US foreign policy but, to an extent, capitalism itself. As he turned toward the root causes of the nation’s intersecting crises, he warned that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” and that “human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns.” Conservatives responded with derision, quickly dubbing it the “malaise speech,” a framing that captured many Americans’ refusal to confront the deeper structural problems Carter had identified.

Reagan ran on this response. He rejected everything Carter had come to represent. Carter, for his part, presided over a series of perceived foreign policy blunders, not all of them self-inflicted, including the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, the Iran Hostage Crisis, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and his actual record was far less radical than his rhetoric suggested. But Reagan seized the moment, casting Carter as weak, naïve, and insufficiently committed to American power and the American way of life, and he won in a landslide.

When Reagan assumed office in 1981, he claimed a mandate to pursue his promised program of unfettered capitalism at home and militant anti-communism abroad, raising the military budget to what were then unprecedented levels. Yet even with this political momentum, he faced constraints. Among them was a public skepticism toward foreign intervention, labeled “Vietnam syndrome,” which posed a direct challenge to his effort to reassert American military primacy on the global stage.

Reagan, however, was not inclined to let public sentiment, democratic constraints, or questions of legality impede his objectives. This saw its most notorious expression in the Iran-Contra Affair, in which administration officials sold weapons to Iran, then in a war of attrition with Saddam’s Iraq, whom the US was backing, in exchange for assistance pressuring Hezbollah to release American hostages in Lebanon, while simultaneously generating funds to support the Contras in Nicaragua. Both were illegal: Congress barred aid to the Contras with the 1982 Boland Amendment, and arms sales to Iran violated US law once it was designated a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984.

Another method in which Reagan sought to bypass political constraints on his policies was through the funding of “freedom fighters” in covert proxy wars, an expensive endeavor financed not only by taxpayer dollars but also by enabling allies to engage in drug trafficking. The tactic was hardly new. Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Nor was this unprecedented for the United States. During the American war in Vietnam, US intelligence enabled local traffickers to fold an existing regional drug trade in support of their counterinsurgency effort. As historian Alfred McCoy has demonstrated, this helped transform the Golden Triangle into the world’s largest opium-producing region. Estimates during the conflict suggested that up to 25% of U.S. troops stationed in Southeast Asia used heroin in some units, and thousands returned home with addictions seeded with the complicity of Washington.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power.

Under Reagan, such complicity only grew. As the administration aggressively expanded punitive anti-drug policing at home under the banner of the “War on Drugs,” it tolerated and indirectly facilitated the cultivation and transport of narcotics when doing so served Cold War priorities. This dynamic was most visible in two of the bloodiest proxy wars of the Reagan era: the Soviet-Afghan War and the Contra War in Nicaragua.

After the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the United States funneled billions of dollars to the mujahideen in an attempt to mire the Soviets in a Vietnam-like quagmire, ultimately producing the most expensive covert operation in US history. It was clear at the time that this policy risked significant “blowback,” although the result was much worse than imagined, but the chance to bleed the Soviets was not one Reagan was willing to forgo.

The extent of US support, indispensable to sustaining the anti-Soviet insurgency, led political scientist Mahmood Mamdani to refer to the insurgency as an “American Jihad.” But the flow of money and arms was not enough on its own, and drug trafficking helped to supplement the effort. Before the war, heroin production in Afghanistan was negligible. By 1989, Afghan-Pakistan supply routes dominated global markets, destabilizing the country and region and creating the conditions for a catastrophic CIA and drug-money enabled, warlord-led civil war that ultimately led to the Taliban’s consolidation of power in 1996.

This heroin not only fueled death and destruction in Afghanistan, where the American-Afghan victory was paid for with the lives of millions of Afghan civilians, but it also boomeranged back. As Mamdani documents, during the Soviet-Afghan jihad, this heroin came to account for some 60% of the heroin circulating on US streets. The consequences were immediate and severe. As a White House drug-policy adviser acknowledged at the time, New York City witnessed a 77% increase in drug-related deaths.

In Central America, a parallel “logic” emerged. The Contras needed cash, and cocaine networks supplied it. The Kerry Committee, convened in the wake of Iran-Contra, and tasked with investigating these links, concluded in 1989 that there was substantial evidence the Contras engaged in drug smuggling and that US officials allowed them to operate without interference.

This support for traffickers unfolded at the very moment the US was intensifying its domestic crackdown on cocaine. During this period, lawmakers and prosecutors entrenched and weaponized legal asymmetries between crack and powder cocaine, driving the militarization of policing and expanding infrastructure of mass incarceration, a campaign that disproportionately targeted and destabilized Black communities across the country.

When Gary Webb, an investigative journalist for the San Jose Mercury News, revealed in 1996 an even more direct connection between CIA awareness of Contra-linked cocaine profits entering the United States and the simultaneous domestic “War on Drugs,” the backlash was swift. Government officials and major media outlets launched a concerted campaign to discredit him, all but ending his career. Nonetheless, many of his findings would soon be corroborated, at least in part, by internal investigations conducted by the CIA and Department of Justice.

Trump’s latest invocation of drugs as a pretext for war with Venezuela is unconvincing on its face. But situated within the long historical record of US complicity in, or calculated indifference to, drug trafficking when it served strategic ends, even when those decisions inflicted direct harm on Americans, it becomes little more than farce. For decades, Washington has treated narcotics not as a public health challenge but as a political instrument, inflating them into an existential national security threat when expedient and minimizing them when inconvenient.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power. This history makes clear that the US cannot credibly condemn other nations for their entanglements in the drug trade until it reckons with its own record as a facilitator of state-sponsored terrorism and narco-trafficking.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Every accusation is a confession. This is clearly true of the Trump administration’s insistence that Venezuela operates as a “narco-state,” exporting terrorism to the US via fentanyl, now labeled as a “weapon of mass destruction.” The charge is not only false, given that virtually no fentanyl enters the country from Venezuela, but transparently political and pretextual.

This hypocrisy was made unmistakable with President Donald Trump’s recent pardon of former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was convicted in 2024 in a US federal court on drug trafficking charges. Hernández presided over a regime long treated as a strategic ally within Washington’s regional security architecture, a reminder that the label of “narco-state” is applied not according to fact but according to the shifting imperatives of US imperial power.

This accusation collapses further when placed in broader historical context. For decades, the most powerful state actors facilitating and protecting narcotics trafficking have not been Washington’s adversaries but Washington itself. Throughout the Cold War and the so-called War on Drugs, the United States, above all through the CIA, repeatedly subordinated drug enforcement to geopolitical priorities, enabling narco-networks so long as they advanced perceived US interests.

These dynamics became especially pronounced in the 1980s, with disastrous consequences both at home and abroad. The decade marked an intensification of the Cold War under Ronald Reagan. His administration insisted that communist “advances” could not only be contained but rolled back. Upon taking office, Reagan launched his promised global offensive, intervening wherever alleged Soviet influence appeared. Turning a blind eye to drug trafficking became a central feature of this crusade, as anti-communism consistently took precedence over anti-narcotics efforts.

Reagan’s rise followed a brief but meaningful thaw. In the wake of Watergate and the Vietnam War, Americans’ faith in political institutions had been profoundly shaken. Years of economic stagnation, inflation, and the reverberations of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo convinced many that the postwar promise of endless upward mobility, the ideological core of the American dream, was collapsing.

It also became impossible to ignore that the US was not only failing to deliver on its economic promise but had also long abandoned the democratic values it claimed to champion. In 1975, the Church Committee laid bare what much of the Global South had known for decades: The United States had been operating as a global anti-democratic force, orchestrating coups and assassinations, sabotaging leftist movements (at home and abroad), and imposing political outcomes that served the interests of American capital rather than the aspirations of people around the world.

Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Then, in 1977, came Jimmy Carter. Carter promised a new foreign policy rooted not in reflexive anti-communism but a commitment to human rights. In doing so, he broke, at least in his rhetoric, with decades of bipartisan Cold War orthodoxy. For the first time, a president openly challenged the axiomatic belief that every leftist movement was a Kremlin proxy that demanded immediate US intervention.

As Carter put it, “We are now free of that inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear,” acknowledging that “for too many years, we’ve been willing to adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs.” Washington, he admitted, had “fought fire with fire, never thinking that fire is better quenched with water,” a strategy that had ultimately backfired.

Carter would also come to critique not only the misguided zealotry of US foreign policy but, to an extent, capitalism itself. As he turned toward the root causes of the nation’s intersecting crises, he warned that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” and that “human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns.” Conservatives responded with derision, quickly dubbing it the “malaise speech,” a framing that captured many Americans’ refusal to confront the deeper structural problems Carter had identified.

Reagan ran on this response. He rejected everything Carter had come to represent. Carter, for his part, presided over a series of perceived foreign policy blunders, not all of them self-inflicted, including the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, the Iran Hostage Crisis, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and his actual record was far less radical than his rhetoric suggested. But Reagan seized the moment, casting Carter as weak, naïve, and insufficiently committed to American power and the American way of life, and he won in a landslide.

When Reagan assumed office in 1981, he claimed a mandate to pursue his promised program of unfettered capitalism at home and militant anti-communism abroad, raising the military budget to what were then unprecedented levels. Yet even with this political momentum, he faced constraints. Among them was a public skepticism toward foreign intervention, labeled “Vietnam syndrome,” which posed a direct challenge to his effort to reassert American military primacy on the global stage.

Reagan, however, was not inclined to let public sentiment, democratic constraints, or questions of legality impede his objectives. This saw its most notorious expression in the Iran-Contra Affair, in which administration officials sold weapons to Iran, then in a war of attrition with Saddam’s Iraq, whom the US was backing, in exchange for assistance pressuring Hezbollah to release American hostages in Lebanon, while simultaneously generating funds to support the Contras in Nicaragua. Both were illegal: Congress barred aid to the Contras with the 1982 Boland Amendment, and arms sales to Iran violated US law once it was designated a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984.

Another method in which Reagan sought to bypass political constraints on his policies was through the funding of “freedom fighters” in covert proxy wars, an expensive endeavor financed not only by taxpayer dollars but also by enabling allies to engage in drug trafficking. The tactic was hardly new. Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Nor was this unprecedented for the United States. During the American war in Vietnam, US intelligence enabled local traffickers to fold an existing regional drug trade in support of their counterinsurgency effort. As historian Alfred McCoy has demonstrated, this helped transform the Golden Triangle into the world’s largest opium-producing region. Estimates during the conflict suggested that up to 25% of U.S. troops stationed in Southeast Asia used heroin in some units, and thousands returned home with addictions seeded with the complicity of Washington.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power.

Under Reagan, such complicity only grew. As the administration aggressively expanded punitive anti-drug policing at home under the banner of the “War on Drugs,” it tolerated and indirectly facilitated the cultivation and transport of narcotics when doing so served Cold War priorities. This dynamic was most visible in two of the bloodiest proxy wars of the Reagan era: the Soviet-Afghan War and the Contra War in Nicaragua.

After the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the United States funneled billions of dollars to the mujahideen in an attempt to mire the Soviets in a Vietnam-like quagmire, ultimately producing the most expensive covert operation in US history. It was clear at the time that this policy risked significant “blowback,” although the result was much worse than imagined, but the chance to bleed the Soviets was not one Reagan was willing to forgo.

The extent of US support, indispensable to sustaining the anti-Soviet insurgency, led political scientist Mahmood Mamdani to refer to the insurgency as an “American Jihad.” But the flow of money and arms was not enough on its own, and drug trafficking helped to supplement the effort. Before the war, heroin production in Afghanistan was negligible. By 1989, Afghan-Pakistan supply routes dominated global markets, destabilizing the country and region and creating the conditions for a catastrophic CIA and drug-money enabled, warlord-led civil war that ultimately led to the Taliban’s consolidation of power in 1996.

This heroin not only fueled death and destruction in Afghanistan, where the American-Afghan victory was paid for with the lives of millions of Afghan civilians, but it also boomeranged back. As Mamdani documents, during the Soviet-Afghan jihad, this heroin came to account for some 60% of the heroin circulating on US streets. The consequences were immediate and severe. As a White House drug-policy adviser acknowledged at the time, New York City witnessed a 77% increase in drug-related deaths.

In Central America, a parallel “logic” emerged. The Contras needed cash, and cocaine networks supplied it. The Kerry Committee, convened in the wake of Iran-Contra, and tasked with investigating these links, concluded in 1989 that there was substantial evidence the Contras engaged in drug smuggling and that US officials allowed them to operate without interference.

This support for traffickers unfolded at the very moment the US was intensifying its domestic crackdown on cocaine. During this period, lawmakers and prosecutors entrenched and weaponized legal asymmetries between crack and powder cocaine, driving the militarization of policing and expanding infrastructure of mass incarceration, a campaign that disproportionately targeted and destabilized Black communities across the country.

When Gary Webb, an investigative journalist for the San Jose Mercury News, revealed in 1996 an even more direct connection between CIA awareness of Contra-linked cocaine profits entering the United States and the simultaneous domestic “War on Drugs,” the backlash was swift. Government officials and major media outlets launched a concerted campaign to discredit him, all but ending his career. Nonetheless, many of his findings would soon be corroborated, at least in part, by internal investigations conducted by the CIA and Department of Justice.

Trump’s latest invocation of drugs as a pretext for war with Venezuela is unconvincing on its face. But situated within the long historical record of US complicity in, or calculated indifference to, drug trafficking when it served strategic ends, even when those decisions inflicted direct harm on Americans, it becomes little more than farce. For decades, Washington has treated narcotics not as a public health challenge but as a political instrument, inflating them into an existential national security threat when expedient and minimizing them when inconvenient.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power. This history makes clear that the US cannot credibly condemn other nations for their entanglements in the drug trade until it reckons with its own record as a facilitator of state-sponsored terrorism and narco-trafficking.

Every accusation is a confession. This is clearly true of the Trump administration’s insistence that Venezuela operates as a “narco-state,” exporting terrorism to the US via fentanyl, now labeled as a “weapon of mass destruction.” The charge is not only false, given that virtually no fentanyl enters the country from Venezuela, but transparently political and pretextual.

This hypocrisy was made unmistakable with President Donald Trump’s recent pardon of former Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernández, who was convicted in 2024 in a US federal court on drug trafficking charges. Hernández presided over a regime long treated as a strategic ally within Washington’s regional security architecture, a reminder that the label of “narco-state” is applied not according to fact but according to the shifting imperatives of US imperial power.

This accusation collapses further when placed in broader historical context. For decades, the most powerful state actors facilitating and protecting narcotics trafficking have not been Washington’s adversaries but Washington itself. Throughout the Cold War and the so-called War on Drugs, the United States, above all through the CIA, repeatedly subordinated drug enforcement to geopolitical priorities, enabling narco-networks so long as they advanced perceived US interests.

These dynamics became especially pronounced in the 1980s, with disastrous consequences both at home and abroad. The decade marked an intensification of the Cold War under Ronald Reagan. His administration insisted that communist “advances” could not only be contained but rolled back. Upon taking office, Reagan launched his promised global offensive, intervening wherever alleged Soviet influence appeared. Turning a blind eye to drug trafficking became a central feature of this crusade, as anti-communism consistently took precedence over anti-narcotics efforts.

Reagan’s rise followed a brief but meaningful thaw. In the wake of Watergate and the Vietnam War, Americans’ faith in political institutions had been profoundly shaken. Years of economic stagnation, inflation, and the reverberations of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo convinced many that the postwar promise of endless upward mobility, the ideological core of the American dream, was collapsing.

It also became impossible to ignore that the US was not only failing to deliver on its economic promise but had also long abandoned the democratic values it claimed to champion. In 1975, the Church Committee laid bare what much of the Global South had known for decades: The United States had been operating as a global anti-democratic force, orchestrating coups and assassinations, sabotaging leftist movements (at home and abroad), and imposing political outcomes that served the interests of American capital rather than the aspirations of people around the world.

Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Then, in 1977, came Jimmy Carter. Carter promised a new foreign policy rooted not in reflexive anti-communism but a commitment to human rights. In doing so, he broke, at least in his rhetoric, with decades of bipartisan Cold War orthodoxy. For the first time, a president openly challenged the axiomatic belief that every leftist movement was a Kremlin proxy that demanded immediate US intervention.

As Carter put it, “We are now free of that inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear,” acknowledging that “for too many years, we’ve been willing to adopt the flawed and erroneous principles and tactics of our adversaries, sometimes abandoning our own values for theirs.” Washington, he admitted, had “fought fire with fire, never thinking that fire is better quenched with water,” a strategy that had ultimately backfired.

Carter would also come to critique not only the misguided zealotry of US foreign policy but, to an extent, capitalism itself. As he turned toward the root causes of the nation’s intersecting crises, he warned that “too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption,” and that “human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns.” Conservatives responded with derision, quickly dubbing it the “malaise speech,” a framing that captured many Americans’ refusal to confront the deeper structural problems Carter had identified.

Reagan ran on this response. He rejected everything Carter had come to represent. Carter, for his part, presided over a series of perceived foreign policy blunders, not all of them self-inflicted, including the Sandinista Revolution in Nicaragua, the Iran Hostage Crisis, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and his actual record was far less radical than his rhetoric suggested. But Reagan seized the moment, casting Carter as weak, naïve, and insufficiently committed to American power and the American way of life, and he won in a landslide.

When Reagan assumed office in 1981, he claimed a mandate to pursue his promised program of unfettered capitalism at home and militant anti-communism abroad, raising the military budget to what were then unprecedented levels. Yet even with this political momentum, he faced constraints. Among them was a public skepticism toward foreign intervention, labeled “Vietnam syndrome,” which posed a direct challenge to his effort to reassert American military primacy on the global stage.

Reagan, however, was not inclined to let public sentiment, democratic constraints, or questions of legality impede his objectives. This saw its most notorious expression in the Iran-Contra Affair, in which administration officials sold weapons to Iran, then in a war of attrition with Saddam’s Iraq, whom the US was backing, in exchange for assistance pressuring Hezbollah to release American hostages in Lebanon, while simultaneously generating funds to support the Contras in Nicaragua. Both were illegal: Congress barred aid to the Contras with the 1982 Boland Amendment, and arms sales to Iran violated US law once it was designated a state sponsor of terrorism in 1984.

Another method in which Reagan sought to bypass political constraints on his policies was through the funding of “freedom fighters” in covert proxy wars, an expensive endeavor financed not only by taxpayer dollars but also by enabling allies to engage in drug trafficking. The tactic was hardly new. Imperial powers had long leveraged drugs to consolidate geopolitical control, from alcohol’s role in Indigenous dispossession to Britain’s forced export of opium into China.

Nor was this unprecedented for the United States. During the American war in Vietnam, US intelligence enabled local traffickers to fold an existing regional drug trade in support of their counterinsurgency effort. As historian Alfred McCoy has demonstrated, this helped transform the Golden Triangle into the world’s largest opium-producing region. Estimates during the conflict suggested that up to 25% of U.S. troops stationed in Southeast Asia used heroin in some units, and thousands returned home with addictions seeded with the complicity of Washington.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power.

Under Reagan, such complicity only grew. As the administration aggressively expanded punitive anti-drug policing at home under the banner of the “War on Drugs,” it tolerated and indirectly facilitated the cultivation and transport of narcotics when doing so served Cold War priorities. This dynamic was most visible in two of the bloodiest proxy wars of the Reagan era: the Soviet-Afghan War and the Contra War in Nicaragua.

After the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the United States funneled billions of dollars to the mujahideen in an attempt to mire the Soviets in a Vietnam-like quagmire, ultimately producing the most expensive covert operation in US history. It was clear at the time that this policy risked significant “blowback,” although the result was much worse than imagined, but the chance to bleed the Soviets was not one Reagan was willing to forgo.

The extent of US support, indispensable to sustaining the anti-Soviet insurgency, led political scientist Mahmood Mamdani to refer to the insurgency as an “American Jihad.” But the flow of money and arms was not enough on its own, and drug trafficking helped to supplement the effort. Before the war, heroin production in Afghanistan was negligible. By 1989, Afghan-Pakistan supply routes dominated global markets, destabilizing the country and region and creating the conditions for a catastrophic CIA and drug-money enabled, warlord-led civil war that ultimately led to the Taliban’s consolidation of power in 1996.

This heroin not only fueled death and destruction in Afghanistan, where the American-Afghan victory was paid for with the lives of millions of Afghan civilians, but it also boomeranged back. As Mamdani documents, during the Soviet-Afghan jihad, this heroin came to account for some 60% of the heroin circulating on US streets. The consequences were immediate and severe. As a White House drug-policy adviser acknowledged at the time, New York City witnessed a 77% increase in drug-related deaths.

In Central America, a parallel “logic” emerged. The Contras needed cash, and cocaine networks supplied it. The Kerry Committee, convened in the wake of Iran-Contra, and tasked with investigating these links, concluded in 1989 that there was substantial evidence the Contras engaged in drug smuggling and that US officials allowed them to operate without interference.

This support for traffickers unfolded at the very moment the US was intensifying its domestic crackdown on cocaine. During this period, lawmakers and prosecutors entrenched and weaponized legal asymmetries between crack and powder cocaine, driving the militarization of policing and expanding infrastructure of mass incarceration, a campaign that disproportionately targeted and destabilized Black communities across the country.

When Gary Webb, an investigative journalist for the San Jose Mercury News, revealed in 1996 an even more direct connection between CIA awareness of Contra-linked cocaine profits entering the United States and the simultaneous domestic “War on Drugs,” the backlash was swift. Government officials and major media outlets launched a concerted campaign to discredit him, all but ending his career. Nonetheless, many of his findings would soon be corroborated, at least in part, by internal investigations conducted by the CIA and Department of Justice.

Trump’s latest invocation of drugs as a pretext for war with Venezuela is unconvincing on its face. But situated within the long historical record of US complicity in, or calculated indifference to, drug trafficking when it served strategic ends, even when those decisions inflicted direct harm on Americans, it becomes little more than farce. For decades, Washington has treated narcotics not as a public health challenge but as a political instrument, inflating them into an existential national security threat when expedient and minimizing them when inconvenient.

The “war on drugs” has never been a genuine campaign to curb the sale or use of narcotics or to protect Americans. Rather, it has functioned as a mechanism for advancing American power. This history makes clear that the US cannot credibly condemn other nations for their entanglements in the drug trade until it reckons with its own record as a facilitator of state-sponsored terrorism and narco-trafficking.