SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

The troubling question isn't whether IFC has environmental policies. It does; the question is whether these policies mean anything when clients consistently fail to comply and the public can't verify whether promised improvements ever materialize.

When the International Finance Corporation, or IFC—the World Bank's private-sector lending arm—invests in developing countries, it promises to uphold rigorous environmental safeguards. But our new analysis of $2 billion in livestock investments reveals an alarming gap between policy and practice that should concern anyone who cares about climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental accountability.

Between 2020 and 2025, the IFC pumped nearly $2 billion into 38 industrial meat, dairy, and feed projects across developing countries. These investments expanded factory farming operations at a time when scientific consensus highlights the urgency of transitioning away from industrial livestock production to protect both people and planet.

The troubling question isn't whether IFC has environmental policies. It does—robust ones, in fact, that 56 other development banks and 130 financial institutions use as benchmarks. The question is whether these policies mean anything when clients consistently fail to comply and the public can't verify whether promised improvements ever materialize.

Our latest report, Unsustainable Investment Part 2, analyzed publicly disclosed environmental risk assessment summaries for all 38 projects, evaluating whether IFC clients adhered to the bank's own requirements for managing biodiversity loss, pollution, and resource use. The findings are sobering.

On biodiversity, most projects offered superficial habitat assessments without the detailed analysis needed to identify critical or natural habitats. Not a single project demonstrated deliberate avoidance of high-value ecosystems—the most important step in preventing irreversible damage. Out of 10 projects facing supply-chain risks from habitat conversion, only 2 reported plans to establish traceability and transition away from destructive suppliers. This matters because industrial livestock threatens over 21,000 species and is the primary driver of deforestation globally.

Without transparent, ongoing disclosure, environmental safeguards become little more than paperwork exercises.

For pollution, the gaps were equally stark. Only one project assessed both ambient conditions and cumulative impacts as required. A few projects also reported exceeding national and international standards for air emissions and wastewater discharge at the time of approval. While many promised future improvements, there's no public evidence these promises were kept. Meanwhile, 29 projects provided no reporting whatsoever on solid waste management compliance—a glaring gap in transparency.

On resource use, the patterns continued. Only one project applied the full water use reduction hierarchy, with most reporting no evidence of even attempting to avoid unnecessary water consumption. This inefficiency is staggering: Industrial livestock uses 33-40% of agriculture's water to produce just 18% of the world's calories.

These findings build on our first Unsustainable Investment report examining client adherence to climate change related requirements. The gaps in adherence to disclosure and mitigation requirements were significant—despite IFC's commitment to align 100% of new investments with the Paris Agreement starting June 2026. For disclosure, while 68% of clients disclosed emissions, the reporting was highly inconsistent. Some reported only Scope 1 or Scope 2; others aggregated both scopes when they should have been separated. For mitigation, over 60% of projects failed to reduce emissions intensity below national averages. And zero projects—out of all 38—managed physical climate risks in their supply chains, despite industrial livestock's extreme vulnerability to climate change.

Perhaps the most concerning discovery is what we couldn't find: evidence of what happens after approval.

IFC's Environmental and Social Action Plans outline corrective measures that clients legally commit to implement over time. Many projects included plans to install pollution controls, improve resource efficiency, or enhance biodiversity management. But IFC doesn't systematically report whether these measures were actually implemented or whether they proved effective.

This absence of verification creates a dangerous accountability vacuum. Without transparent, ongoing disclosure, environmental safeguards become little more than paperwork exercises—compliance theater that manages reputational risk rather than environmental impact.

This matters far beyond IFC's portfolio. As the world's largest development finance institution focused on emerging economies, IFC functions as a standard setter. When IFC finances industrial livestock expansion despite weak compliance with environmental requirements, it sends a signal to global markets that such investments are "sustainable"—even when evidence suggests otherwise.

Consider the context: Industrial livestock contributes up to 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions, occupies 70% of agricultural land, and drives the planetary boundary transgressions that scientists warn threaten Earth's capacity to support human civilization. The World Bank's own 2024 report, Recipe for a Livable Planet, acknowledges that "to protect our planet, we need to transform the way we produce and consume food."

Yet IFC continues to invest billions in expanding the very systems the World Bank identifies as unsustainable. Civil society organizations have repeatedly documented environmental and social harms from IFC-financed factory farms in Ecuador, Brazil, China, and Mongolia—harm that occurs despite IFC's safeguards being applied.

This isn't an argument against development finance. It's a call for development finance that actually delivers sustainable development.

IFC must fundamentally reassess whether industrial livestock expansion is compatible with its mission. The institution should redirect financing toward food production systems that are demonstrably sustainable—agroecological approaches, diversified farming systems, and plant-based proteins that can deliver food security without exacerbating environmental crises.

Equally urgent: IFC must mandate full, transparent disclosure of environmental compliance throughout project lifecycles—not just at approval. Independent verification and meaningful consequences for non-compliance must replace the current honor system. Without enforcement, the world's most influential environmental safeguards are effectively optional.

Billions in public development finance continue flowing to industrial operations that drive climate change, biodiversity collapse, pollution, and resource depletion.

The stakes extend beyond any single institution. With IFC's president announcing plans to double annual agribusiness investments to $9 billion by 2030, and the Paris Agreement alignment deadline now extended to June 2026, the window for course correction is rapidly closing.

As 130 financial institutions benchmark their own environmental standards against IFC's Performance Standards, the compliance failures we've documented likely exist throughout the development finance sector. Systemic problems require systemic solutions.

The evidence is clear: IFC's environmental safeguards are robust on paper but weakened by inconsistent client adherence, limited transparency, and absent enforcement. The current approach manages compliance risk rather than environmental impact—a fundamental misalignment with both IFC's stated mission and the urgent imperatives of our environmental moment.

Seven of nine planetary boundaries have already been breached. The Earth system is under unprecedented stress. Yet billions in public development finance continue flowing to industrial operations that drive climate change, biodiversity collapse, pollution, and resource depletion.

The question isn't whether IFC can afford to change course. It's whether we can afford for it not to.

If the Global South acts now, it can help build a future where algorithms bridge divides instead of deepening them—where they enable peace, not war.

The world stands on the brink of a transformation whose full scope remains elusive. Just as steam engines, electricity, and the internet each sparked previous industrial revolutions, artificial intelligence is now shaping what has been dubbed the Fourth Industrial Revolution. What sets this new era apart is the unprecedented speed and scale with which AI is being deployed—particularly in the realms of security and warfare, where technological advancement rarely keeps pace with ethics or regulation.

As the United States and its Western allies pour billions into autonomous drones, AI-driven command systems, and surveillance platforms, a critical question arises: Is this arms race making the world safer—or opening the door to geopolitical instability and even humanitarian catastrophe?

The reality is that the West’s focus on achieving military superiority—especially in the digital domain—has sidelined global conversations about the shared future of AI. The United Nations has warned in recent years that the absence of binding legal frameworks for lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) could lead to irreversible consequences. Yet the major powers have largely ignored these warnings, favoring strategic autonomy in developing digital deterrence over any multilateral constraints. The nuclear experience of the 20th century showed how a deterrence-first logic brought humanity to the edge of catastrophe; now, imagine algorithms that can decide to kill in milliseconds, unleashed without transparent global commitments.

So far, it is the nations of the Global South that have borne the heaviest cost of this regulatory vacuum. From Yemen to the Sahel, AI-powered drones have enabled attacks where the line between military and civilian targets has all but disappeared. Human rights organizations report a troubling rise in civilian casualties from drone strikes over the past decade, with no clear mechanisms for compensation or legal accountability. In other words, the Global South is not only absent from decision-making but has become the unintended testing ground for emerging military technologies—technologies often shielded from public scrutiny under the guise of national security.

Ultimately, the central question facing humanity is this: Do we want AI to replicate the militaristic logic of the 20th century—or do we want it to help us confront shared global challenges, from climate change to future pandemics?

But this status quo is not inevitable. The Global South—from Latin America and Africa to West and South Asia—is not merely a collection of potential victims. It holds critical assets that can reshape the rules of the game. First, these countries have youthful, educated populations capable of steering AI innovation toward civilian and development-oriented goals, such as smart agriculture, early disease detection, climate crisis management, and universal education. For instance, multilateral projects involving Indian specialists in the fight against malaria using artificial intelligence.

Second, the South possesses a collective historical memory of colonialism and technological subjugation, making it more attuned to the geopolitical dangers of AI monopolies and thus a natural advocate for a more just global order. Third, emerging coalitions—like BRICS+ and the African Union’s digital initiatives—demonstrate that South-South cooperation can facilitate investment and knowledge exchange independently of Western actors.

Still, international political history reminds us that missed opportunities can easily turn into looming threats. If the Global South remains passive during this critical moment, the risk grows that Western dominance over AI standards will solidify into a new form of technological hegemony. This would not merely deepen technical inequality—it would redraw the geopolitical map and exacerbate the global North-South divide. In a world where a handful of governments and corporations control data, write algorithms, and set regulatory norms, non-Western states may find themselves forced to spend their limited development budgets on software licenses and smart weapon imports just to preserve their sovereignty. This siphoning of resources away from health, education, and infrastructure—the cornerstones of sustainable development—would create a vicious cycle of insecurity and underdevelopment.

Breaking out of this trajectory requires proactive leadership by the Global South on three fronts. First, leading nations—such as India, Brazil, Indonesia, and South Africa—should establish a ”Friends of AI Regulation” group at the U.N. General Assembly and propose a draft convention banning fully autonomous weapons. The international success of the landmine treaty and the Chemical Weapons Convention shows that even in the face of resistance from great powers, the formation of “soft norms” can pave the way toward binding treaties and increase the political cost of defection.

Second, these countries should create a joint innovation fund to support AI projects in healthcare, agriculture, and renewable energy—fields where benefits are tangible for citizens and where visible success can generate the social capital needed for broader international goals. Third, aligning with Western academics and civil society is vital. The combined pressure of researchers, human rights advocates, and Southern policymakers on Western legislatures and public opinion can help curb the influence of military-industrial lobbies and create political space for international cooperation.

In addition, the Global South must invest in developing its own ethical standards for data use and algorithmic governance to prevent the uncritical adoption of Western models that may worsen cultural risks and privacy violations. Brazil’s 2021 AI ethics framework illustrates that local values can be harmonized with global principles like transparency and algorithmic fairness. Adapting such initiatives at the regional level—through bodies like the African Union or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization—would be a major step toward establishing a multipolar regime in global digital governance.

Of course, this path is not without obstacles. Western powers possess vast economic, political, and media tools to slow such efforts. But history shows that transformative breakthroughs often emerge from resistance to dominant systems. Just as the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1960s expanded the Global South’s agency during the Cold War, today, it can spearhead AI regulation to reshape the power-technology equation in favor of a fairer world order.

Ultimately, the central question facing humanity is this: Do we want AI to replicate the militaristic logic of the 20th century—or do we want it to help us confront shared global challenges, from climate change to future pandemics? The answer depends on the political will and bold leadership of countries that hold the world’s majority population and the greatest potential for growth. If the Global South acts now, it can help build a future where algorithms bridge divides instead of deepening them—where they enable peace, not war.

The time for action is now. Silence means ceding the future to entrenched powers. Coordinated engagement, on the other hand, could move AI from a minefield of geopolitical interests to a shared highway of cooperation and human development. This is the mission the Global South must undertake—not just for itself, but for all of humanity.

The SDGs are largely an investment agenda into human capital and infrastructure, yet many developing countries cannot finance these investments at reasonable terms.

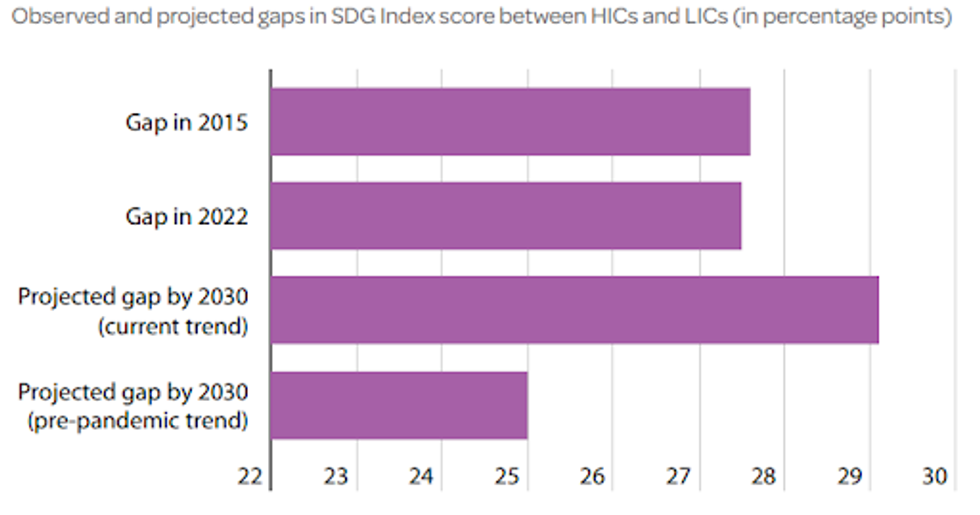

July 2023 was the hottest month ever recorded on Earth. From the rising impacts of climate change evidenced by the deadly wildfires across the world to the growing global inequities, it is clear that we have reached a decisive moment for achieving sustainable development. Furthermore, the gap between rich and poor countries on sustainable development outcomes is at risk of being larger in 2030 than it was in 2015, as highlighted in the 2023 Sustainable Development Report (which includes the SDG Index).

This is largely due to inefficiencies in the international financing system for financing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). To avoid a lost decade for convergence in sustainable development, we need long-term national SDG plans, backed by adequate financing, combined with global and regional cooperation.

The SDGs are largely an investment agenda into human capital and infrastructure, yet many developing countries cannot finance these investments at reasonable terms. The SDG financing gap was recently estimated by the United Nations at $4 trillion (or around 4% of world output). A rather modest amount relative to the size of the global economy, but very large relative to developing countries’ gross domestic product (likely 10-20 % or more). High-income countries managed to mobilize more than $17 trillion in post-Covid-19 recovery at zero or near-zero interest rates. By contrast, many developing countries lack access to capital markets, and even if they have access, they pay higher interest rates and face shorter repayment terms. This is the perfect recipe for getting stuck into liquidity crises, the “poverty trap,” and social unrest.

While it is often argued that the high interest rates faced by developing countries simply compensate for their higher risks of default, this presumption is contradicted by the historical record: The higher interest rates more than compensate for the higher risks of default of developing countries. As documented by Meyer, Reinhart, and Trebesch (2022), the long-term returns on risky sovereign bonds have been far higher than the returns on “safe” United States and United Kingdom securities, even taking into account the episodes of default. In reality, the higher interest rates faced by developing countries reflect two fundamental inefficiencies of the international financial markets:

Access to financing must be linked with SDG gaps and countries’ efforts to achieve sustainable development. There are two crucial levers to increase access to long-term SDG financing in developing countries.

First, sovereign risk-rating agencies and financial institutions at large must capture the growth potential of investing into sustainable development and better understand countries’ SDG efforts. As emphasized by U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres:

The divergence between developed and developing countries is becoming systemic—a recipe for instability, crisis, and forced migration. These imbalances are not a bug, but a feature of the global financial system. They are inbuilt and structural. They are the product of a system that routinely ascribes poor credit ratings to developing economies, starving them of private finance.

Whether it is via sustainability-themed bonds or via significant revisions of credit-risk rating methodologies, the cost of borrowing and maturities must better reflect SDG efforts and commitments in developing countries. There is a clear business case for this. When Benin worked with private financial institutions to issue the first African SDG Bond in July 2021, it managed to mobilize €500 million with a 20-base points greenium (i.e. lower cost of borrowing than its typical sovereign bond) and an average maturity of 12.5 years from the international capital market. New mechanisms, such as new swap lines and the expansion of the IMF Special Drawing Rights, can help increase guarantees and extend lender-of-last-resort protection. Partnerships between private financial institutions, governments, and civil society organizations in the development of long-term pathways and investment frameworks, as well as in the monitoring of policies and impacts, will help reduce risks and increase accountability.

Second, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) should operate at a much higher scale. Thanks to their governance system, MDBs—including the World Bank and regional development banks—can borrow and lend to their member countries at lower interest rates. When MDBs borrow on international markets, they offer more guarantees to lenders than individual countries because the loans are guaranteed by all their members. Yet, MDBs operate at a scale which is largely insufficient.

In September 2022, Guterres introduced the SDG Stimulus. As emphasized by Sustainable Development Solutions Network Leadership Council members, the urgent objective of the SDG Stimulus is to address—in practical terms and at scale—the chronic shortfall of international SDG financing facing the low income countries and low-and-middle-income countries, and to ramp up financing flows by at least $500 billion by 2025. The most important component of the stimulus plan is a massive expansion of loans by the MDBs, backed by new rounds of paid-in capital by high-income country members. Unfortunately, the commitment made at the recent Paris Summit for a Global Financing Pact—an overall increase of $200 billion of MDBs’ lending capacity over the next 10 years (at $20 billion per year)—remains vastly insufficient.

At the global level, the SDG financing gap is largely the result of missed investment opportunities caused by an inappropriate financing framework. Moving forward, we must channel a larger share of global savings (currently equivalent to around $28 trillion per year) to activities that promote sustainable development, especially in developing countries. And the notion of risk must be reconsidered to recognize the long-term returns of investing into sustainable development and the cost of inaction.

In any case, greater access to financing from private capital markets, debt relief & restructuration, increased Official Development Assistance, foreign direct investments, and MDB lending must be associated with long-term investment planning, fiscal frameworks, project implementation, financial operations, and relations with partner institutions in developing countries, in order to be able to channel much larger funds into long-term sustainable development.

This year’s United Nations General Assembly and SDG Summit, and the upcoming G20 meeting in India, are important milestones to reform the global financial system and to promote cooperation and pathways for sustainable development.