“This is an empty deal," said Nikki Reisch, the Center for International Environmental Law's (CIEL) director of climate and energy program. "COP30 provides a stark reminder that the answers to the climate crisis do not lie inside the climate talks—they lie with the people and movements leading the way toward a just, equitable, fossil-free future. The science is settled and the law is clear: We must keep fossil fuels in the ground and make polluters pay."

COP30 was notable in that it was the first international climate conference to which the US did not send a formal delegation, following President Donald Trump's decision to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement. Yet, even without a Trump administration presence, observers were disappointed in the power of fossil fuel-producing countries to derail ambition. The final document also failed to heed the warning of a fire that broke out in the final days of the talks, which many saw as a symbol for the rapid heating of the Earth.

“Rich polluting countries that caused this crisis have blocked the breakthrough that we needed at COP30."

“The venue bursting into flames couldn’t be a more apt metaphor for COP30’s catastrophic failure to take concrete action to implement a funded and fair fossil fuel phaseout,” said Jean Su, energy justice director at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a statement. “Even without the Trump administration there to bully and cajole, petrostates once again shut down meaningful progress at this COP. These negotiations keep hitting a wall because wealthy nations profiting off polluting fossil fuels fail to offer the needed financial support to developing countries and any meaningful commitment to move first.”

The talks on a final deal nearly broke down between Friday and Saturday as a coalition of more than 80 countries who favored more ambitious language faced off against fossil fuel-producing nations like Saudi Arabia, Russia, and India.

During the dispute, Colombia's delegate said the deal "falls far short of reflecting the magnitude of the challenges that parties—especially the most vulnerable—are confronting on the ground," according to BBC News.

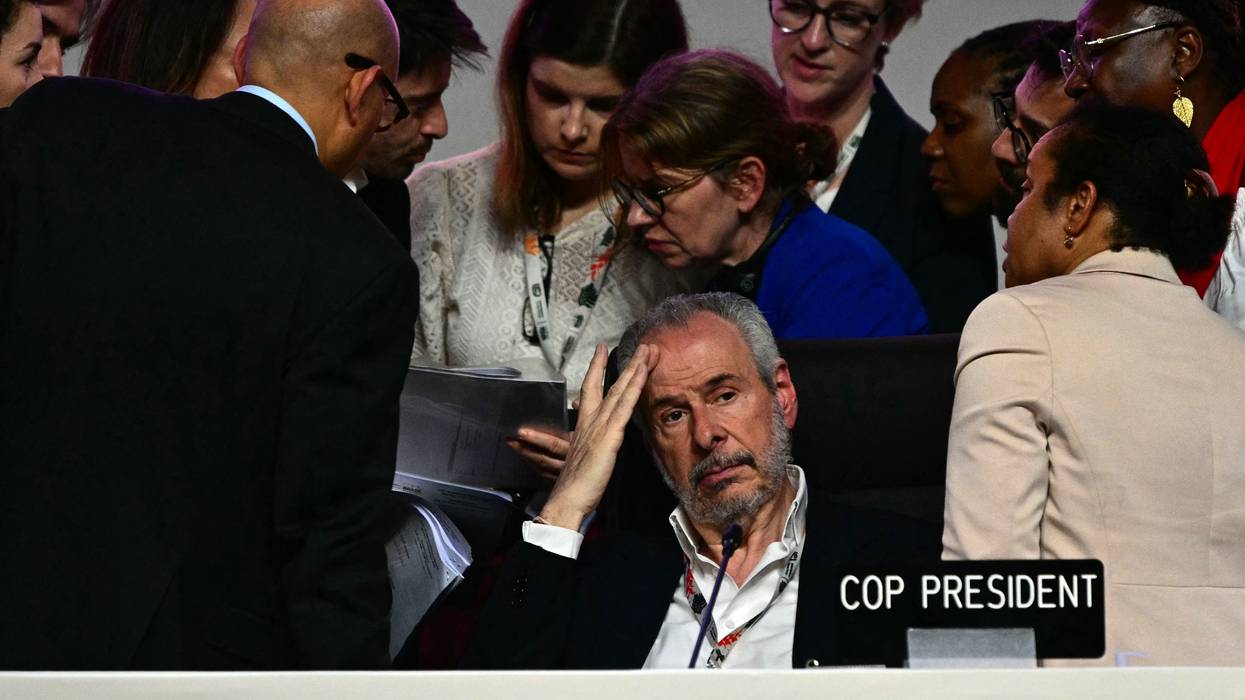

Finally, a deal was struck around 1:35 pm local time, The Guardian reported. The deal circumvented the fossil fuel debate by affirming the "United Arab Emirates Consensus," referring to when nations agreed to transition away from fossil fuels at COP28 in the UAE. In addition, COP President André Corrêa do Lago said that stronger language on the fossil fuel transition could be negotiated at an interim COP in six months.

On deforestation, the deal similarly restated the COP26 pledge to halt tree felling by 2030 without making any new plans or commitments.

Climate justice advocates were also disappointed in the finance commitments from Global North to Global South countries. While wealthier countries pledged to triple adaptation funds to $120 billion per year, many saw the amount as insufficient, and the funds were promised by 2035, not 2030 as poorer countries had wanted.

"We must reflect on what was possible, and what is now missing: the road maps to end forest destruction, and fossil fuels, and an ongoing lack of finance," Greenpeace Brazil executive director Carolina Pasquali told The Guardian. "More than 80 countries supported a transition away from fossil fuels, but they were blocked from agreeing on this change by countries that refused to support this necessary and urgent step. More than 90 countries supported improved protection of forests. That too did not make it into the final agreement. Unfortunately, the text failed to deliver the scale of change needed.”

Climate campaigners did see hope in the final agreement's strong language on human rights and its commitment to a just transition through the Belém Action Mechanism, which aims to coordinate global cooperation toward protecting workers and shifting to clean energy.

“It’s a big win to have the Belém Action Mechanism established with the strongest-ever COP language around Indigenous and worker rights and biodiversity protection,” Su said. “The BAM agreement is in stark contrast to this COP’s total flameout on implementing a funded and fair fossil fuel phaseout.”

Oxfam Brasil executive director Viviana Santiago struck a similar note, saying: “COP30 offered a spark of hope but far more heartbreak, as the ambition of global leaders continues to fall short of what is needed for a livable planet. People from the Global South arrived in Belém with hope, seeking real progress on adaptation and finance, but rich nations refused to provide crucial adaptation finance. This failure leaves the communities at the frontlines of the climate crisis exposed to the worst impacts and with few options for their survival."

"The climate movement will be leaving Belém angry at the lack of progress, but with a clear plan to channel that anger into action."

Romain Ioualalen, global policy lead at Oil Change International, said: “Rich polluting countries that caused this crisis have blocked the breakthrough that we needed at COP30. The EU, UK, Australia, and other wealthy nations are to blame for COP’s failure to adopt a road map on fossil fuels by refusing to commit to phase out first or put real public money on the table for the crisis they have caused. Still, amid this flawed outcome, there are glimmers of real progress. The Belém Action Mechanism is a major win made possible by movements and Global South countries that puts people’s needs and rights at the center of climate action."

Indigenous leaders applauded language that recognized their land rights and traditional knowledge as climate solutions and recognized people of African descent for the first time. However, they still argued the COP process could do more to enable the full participation of Indigenous communities.

"Despite being referred to as an Indigenous COP and despite the historic achievement in the Just Transition Programme, it became clear that Indigenous Peoples continue to be excluded from the negotiations, and in many cases, we were not given the floor in negotiation rooms. Nor have most of our proposals been incorporated," said Emil Gualinga of the Kichwa Peoples of Sarayaku, Ecuador. "The militarization of the COP shows that Indigenous Peoples are viewed as threats, and the same happens in our territories: Militarization occurs when Indigenous Peoples defend their rights in the face of oil, mining, and other extractive projects."

Many campaigners saw hope in the alliances that emerged beyond the purview of the official UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) process, from a group of 24 countries who have agreed to collaborate on a plan to transition off fossil fuels in line with the Paris goals of limiting temperature increases to 1.5°C to the Indigenous and civil society activists who marched against fossil fuels in Belém.

“The barricade that rich countries built against progress and justice in the COP30 process stands in stark contrast to the momentum building outside the climate talks," Ioualalen said. "Countries and people from around the world loudly are demanding a fair and funded phaseout, and that is not going to stop. We didn’t win the full justice outcome we need in Belém, but we have new arenas to keep fighting."

In April 2026, Colombia and the Netherlands will cohost the First International Conference on Fossil Fuel Phaseout. At the same time, 18 countries have signed on in support of a treaty to phase out fossil fuels.

"However big polluters may try to insulate themselves from responsibility or edit out the science, it does not place them above the law," Reisch said. "That’s why governments committed to tackling the crisis at its source are uniting to move forward outside the UNFCCC—under the leadership of Colombia and Pacific Island states—to phase out fossil fuels rapidly, equitably, and in line with 1.5°C. The international conference on fossil fuel phaseout in Colombia next April is the first stop on the path to a livable future. A Fossil Fuel Treaty is the road map the world needs and leaders failed to deliver in Belém.”

These efforts must contend with the influence not only of fossil fuel-producing nations, but also the fossil fuel industry itself, which sent a record 1,602 lobbyists to COP30.

“COP30 witnessed a record number of lobbyists from the fossil fuel industry and carbon capture sector," said CIEL fossil economy director Lili Fuhr. "With 531 Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) lobbyists—surpassing the delegations of 62 nations—and over 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists making up 1 in every 25 attendees, these industries deeply infiltrated the talks, pushing dangerous distractions like CCS and geoengineering. Yet, this unprecedented corporate capture has met fiercer resistance than ever with people and progressive governments—with science and law on their side—demanding a climate process that protects people and planet over profit."

Indeed, Jamie Henn of Make Polluters Pay told Common Dreams that the polluting nations and industries overplayed their hand, arguing that Big Oil and "petro states, including the United States, did their best to kill progress at COP30, stripping the final agreement of any mention of fossil fuels. But their opposition may have backfired: More countries than ever are now committed to pursuing a phaseout road map and this April's conference in Colombia on a potential 'Fossil Fuel Treaty' has been thrust into the spotlight, with support from Brazil, the European Union, and others."

Henn continued: "The COP negotiations are a consensus process, which means it's nearly impossible to get strong language on fossil fuels past blockers like Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the US, who skipped these talks, but clearly opposed any meaningful action. But you can't block reality: The transition from fossils to clean energy is accelerating every day."

"From Indigenous protests to the thunderous rain on the roof of the conference every afternoon, this COP in the heart of the Amazon was forced to confront realities that these negotiations so often try to ignore," he concluded. "I think the climate movement will be leaving Belém angry at the lack of progress, but with a clear plan to channel that anger into action. Climate has always been a fight against fossil fuels, and that battle is now fully underway."