The current administration also significantly weakened the President’s Emergency Fund for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). These cuts, plus the closing of USAID, severely limit the international efforts of humanitarian organizations which work to control mother-to-child transmission of HIV. If funding for HIV prevention and treatment continues to fall, by 2040, an estimated 3 million children will contract HIV and nearly 1.8 million will die of AIDS-related causes.

As if that were not enough, the administration pulled out of the vaccine alliance Gavi, an international organization that has paid for more than 1 billion children to be vaccinated worldwide. This allows vaccine-preventable diseases to flourish among unvaccinated and vulnerable children. Many will be permanently disabled or die.

The administration turning its back on the “sh** hole” countries will come back and bite America in the ass, with innocents suffering the most.

The administration has directed these closings of international programs overwhelmingly against Black and brown people who, according to the president, live in “sh** hole” countries. This is his program of “America First,” where “those” people don’t matter—where their children don’t matter.

Moral judgement aside, helping those suffering in other countries is actually in our best interest. Not only would this show some badly needed humanity and compassion, it is also the best public health approach to protect all of us from contagious diseases.

But too many in the United States live in a right-wing news bubble where they aren’t aware of the suffering in the “sh** hole” countries or simply don’t care. And so many don’t realize that the diseases that foreign aid was working to control (AIDS, tuberculosis, polio, Ebola, and vaccine-preventable diseases) endanger us all. They are not just “their problem,” they are also “our problem.” As these diseases spread and multiply in other countries, the nature of the US economy and international trade will bring them here. The administration turning its back on the “sh** hole” countries will come back and bite America in the ass, with innocents suffering the most. Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases are not “the cost of doing business,” as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Deputy Director, Ralph Abraham, MD, callously stated. The US has managed to “do business” while controlling vaccine-preventable disease for decades.

But the administration’s war on children does not stop with the “sh** hole” countries. Here in the US, the “Big Beautiful Bill” made draconian funding cuts to safety-net programs. This intentionally endangers children in millions of US families because it ends access to healthcare and adequate nutrition.

Even that was not enough. Robert F Kennedy Jr., secretary of Health and Human Services, has promoted an anti-science, anti-vaccine agenda by weaponizing the CDC to reduce the availability of vaccines in the US and to keep up a constant drumbeat of anti-vaccine disinformation. The CDC is no longer a trusted source of science-based public health information; it is now a clearinghouse for Kennedy’s anti-science, anti-vaccine misinformation, conspiracies, and lies. Many parents are rightfully confused by the barrage of anti-vaccine propaganda coming from Kennedy; vaccine hesitance is rising, resulting in soaring cases of measles, whooping cough, influenza and tetanus among children. And more will come as Kennedy’s flood of misinformation and fear-mongering about vaccines continues, supported by the highest levels of the administration.

Among this group dangerous beliefs are developing, exemplified by the comments of the Kennedy-appointed Chair of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Kirk Milhoan. He recently voiced the belief that the individual freedom to refuse vaccines is greater than the freedom to choose not to be infected by contagious diseases. He questions requirements for childhood vaccines, and believes that declining vaccination rates are an opportunity to see what happens when vaccine-preventable diseases run rampant, rather than the tragedy that it is. This is not a sane or ethical experiment; history tells us the answer: The viruses and bacteria will win, and children will suffer.

Kennedy and the administration recently began this unethical experiment when they cut the number of vaccines in the childhood vaccine schedule, guaranteed to reduce vaccine use. Kennedy removed recommendations for rotavirus, Covid-19, influenza, RSV, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and meningococcal vaccines. These are serious diseases that cause children to suffer and die.

They claim that the new recommendations allow parents the “freedom of choice” about these vaccines, after “shared decision-making,” but this has always been the case for childhood vaccines. What they say is freedom has a tragic cost, and this version of freedom effectively declares that the death of children by vaccine-preventable diseases is an acceptable cost, the cost of doing business, with that cost paid in kids’ lives.

Some may call this freedom. We call it a war on children.

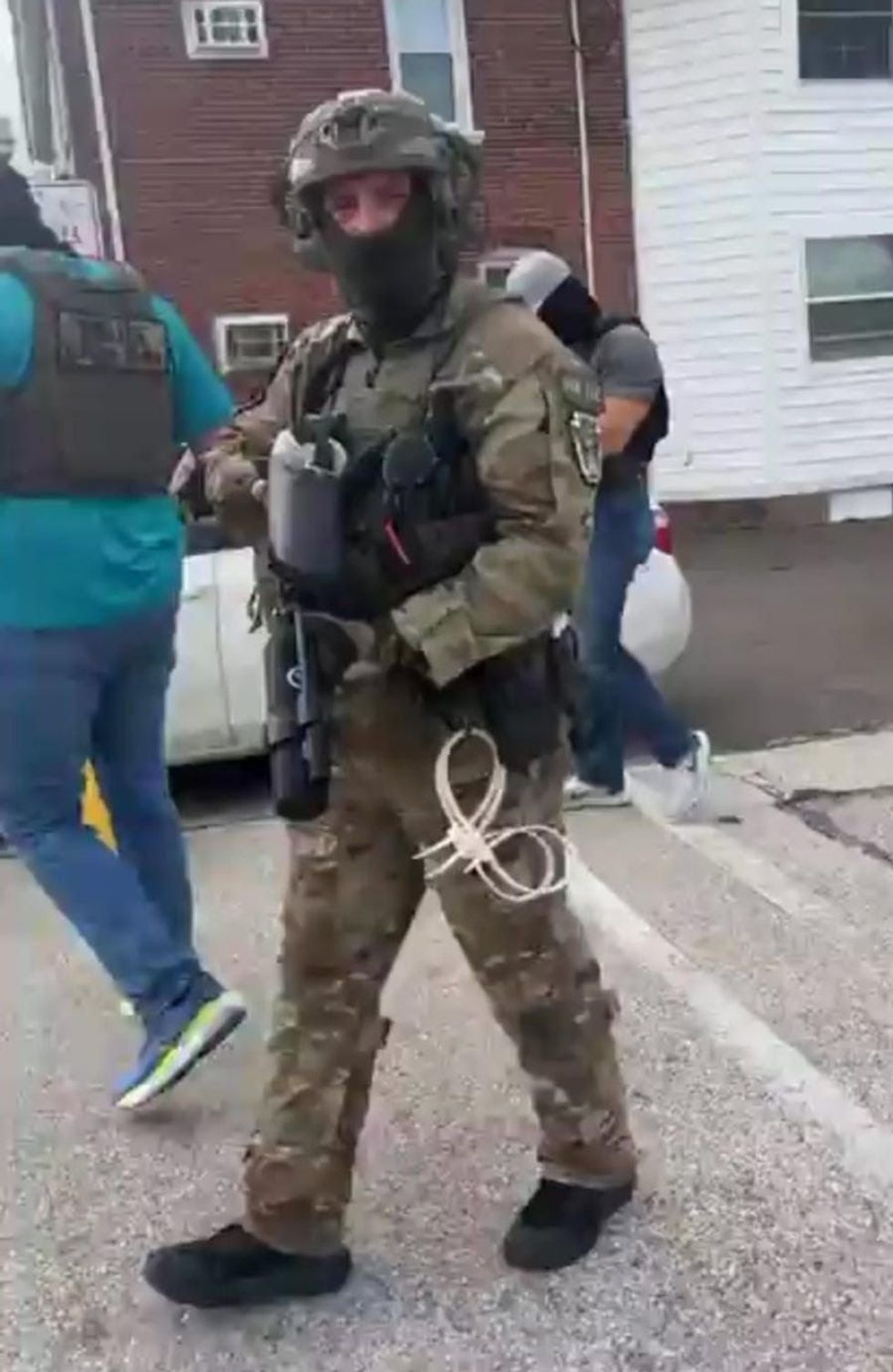

A military-style ICE raid occurs at a grocery story in West Norriton,

A military-style ICE raid occurs at a grocery story in West Norriton,