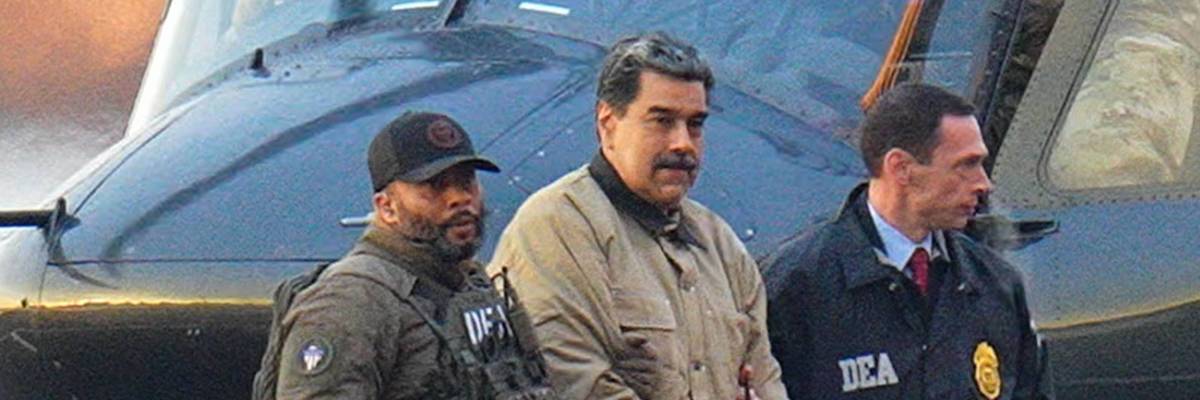

Nicolas Maduro is seen in handcuffs after landing at a Manhattan helipad, escorted by heavily armed Federal agents as they make their way into an armored car en route to a Federal courthouse in Manhattan on January 5, 2026 in New York City.

Trump's Kidnapping of Maduro Is a Threat to Sovereignty Everywhere

The response to this act, regardless of one’s political orientation or views on the Maduro government, will determine whether the concepts of international law, multilateralism, and the self-determination of peoples retain any meaning in the 21st century.

On January 3, 2026, the United States did not merely bomb a sovereign country and capture its president. It displayed, in the most unambiguous terms, a total defiance of the post-war international order that it helped create. When US special forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife and National Assembly Deputy Cilia Flores from Caracas and transported them to a Brooklyn jail, they did not simply violate Venezuelan sovereignty. They declared that sovereignty itself, for any nation that refuses subordination to US imperialism, holds no weight.

As Nicolás Maduro Guerra, the president’s son, stated before Venezuela’s National Assembly: “If we normalize the kidnapping of a head of state, no country is safe. Today it’s Venezuela. Tomorrow, it could be any nation that refuses to submit.”

The response to this act, regardless of one’s political orientation or views on the Maduro government, will determine whether the concepts of international law, multilateralism, and the self-determination of peoples retain any meaning in the 21st century. This is not a question for the left alone. It is a question for every nation, every government, and every citizen who believes that the world should not be governed by the principle that might makes right.

The Logic of Hyper-Imperialism Unveiled

What distinguishes the current phase of US foreign policy from earlier periods of intervention is its brazenness. When the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954, Washington maintained the pretense of responding to communist subversion. When American forces invaded Panama in 1989 to capture Manuel Noriega, the justification was framed within a discourse of law enforcement. The history of US intervention in Latin America spans over 40 successful regime changes in slightly less than a century, according to Harvard scholar John Coatsworth.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them.

But President Donald Trump’s announcement that the United States would “run” Venezuela represents something qualitatively different. Here there is no pretense. When asked about the operation, Trump invoked the Monroe Doctrine and said that these are called “Donroe Doctrine,” signaling that the Western Hemisphere remains a zone of US dominion—an assertion clearly made in the National Security Strategy launched in November 2025. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s subsequent clarification that the US would merely extract policy changes and oil access did nothing to soften the nakedness of the imperial project.

This represents what we at the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research have identified as “hyper-imperialism,” a dangerous and decadent stage of imperialism. Facing the erosion of its economic and political dominance and the rise of alternative centers of power (mainly in Asia) US imperialism increasingly relies on its uncontested military strength. The Chatham House analysis is unequivocal: This constitutes a significant violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the United Nations Charter. There was no Security Council mandate, nor any claims to self-defense.

The post-1945 international order established the formal principle that states possess sovereign equality and that force against another state’s territorial integrity is prohibited. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter was designed precisely to prevent the powerful from treating the world as their domain, which the US has now blatantly ignored.

The Test for Global South Solidarity

The kidnapping of President Maduro poses an existential question to the discourse of “multipolarity.” While the seeds of a multipolar world order may exist (China’s economic rise, the increasing political assertiveness of Global South countries, BRICS and its expansion, the increasing trade in local currencies) they have proven to be extremely limited in the face of the US unilateral use of force. This is an uncomfortable truth.

The initial responses from governments suggest the difficulty of moving from rhetorical condemnation to material constraint. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva correctly identified the stakes when he condemned the capture as crossing “an unacceptable line” and warned that “attacking countries, in flagrant violation of international law, is the first step toward a world of violence, chaos, and instability.” Colombian President Gustavo Petro rejected “the aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and of Latin America.” Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum declared that “the Americas do not belong to any doctrine or any power.” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi condemned US military intervention and called for the release of President Maduro, saying, “We don’t believe that any country can act as the world’s police.”

The groundswell of opposition confronts a structural problem: The institutions designed to prevent such actions are incapable of constraining the permanent members of the Security Council. The United States can veto any resolution condemning its behavior. The emergency Security Council meeting convened at the request of Venezuela and Colombia produced denunciations but no enforcement mechanism.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them. Trump’s threats against Cuba and Colombia underscore this point.

Sovereignty, Resources, and the Right to Self-Determination

The pattern is well established with the successive overthrowing of heads of states when they tried to implement land reform like Árbenz in Guatemala, nationalize national resources under Salvador Allende in Chile and Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran. The thread continues to the present situation in Venezuela.

While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist.

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion barrels. Trump made no effort to disguise the centrality of oil, announcing that American companies would rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry and the US would be “selling oil, probably in much larger doses.” The maritime blockade preceding the military operation served the explicit purpose of strangling the country economically.

Yet the entire trajectory of the US Venezuela policy since 2001, from funding opposition groups to the 2002 coup attempt, to Operation Gideon in 2020, to the “maximum pressure” sanctions, has been designed to prevent Venezuela from making free choices. The assault accelerated after Venezuela enacted its 2001 Hydrocarbons Law asserting sovereign control over oil resources.

Conclusion

The kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and National Assembly deputy Cilia Flores should compel a fundamental reassessment of the state of the international order. The formal institutions and legal frameworks that were supposed to prevent great power aggression have failed to constrain Washington’s imperialist aggressions. This places an enormous responsibility on the governments and peoples of the Global South. The debates around multipolarity, BRICS, South-South cooperation, and de-dollarization are rendered academic if they do not translate into the practical capacity to impose costs on actions like the invasion of Venezuela. Ultimately, the imperialist aggression against Venezuela has repercussions for governments and peoples around the world, regardless of their ideological orientation or views on the Maduro government. While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist. The defense of Venezuelan people’s sovereignty, after all, is a defense of the sovereignty of all our nations.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On January 3, 2026, the United States did not merely bomb a sovereign country and capture its president. It displayed, in the most unambiguous terms, a total defiance of the post-war international order that it helped create. When US special forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife and National Assembly Deputy Cilia Flores from Caracas and transported them to a Brooklyn jail, they did not simply violate Venezuelan sovereignty. They declared that sovereignty itself, for any nation that refuses subordination to US imperialism, holds no weight.

As Nicolás Maduro Guerra, the president’s son, stated before Venezuela’s National Assembly: “If we normalize the kidnapping of a head of state, no country is safe. Today it’s Venezuela. Tomorrow, it could be any nation that refuses to submit.”

The response to this act, regardless of one’s political orientation or views on the Maduro government, will determine whether the concepts of international law, multilateralism, and the self-determination of peoples retain any meaning in the 21st century. This is not a question for the left alone. It is a question for every nation, every government, and every citizen who believes that the world should not be governed by the principle that might makes right.

The Logic of Hyper-Imperialism Unveiled

What distinguishes the current phase of US foreign policy from earlier periods of intervention is its brazenness. When the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954, Washington maintained the pretense of responding to communist subversion. When American forces invaded Panama in 1989 to capture Manuel Noriega, the justification was framed within a discourse of law enforcement. The history of US intervention in Latin America spans over 40 successful regime changes in slightly less than a century, according to Harvard scholar John Coatsworth.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them.

But President Donald Trump’s announcement that the United States would “run” Venezuela represents something qualitatively different. Here there is no pretense. When asked about the operation, Trump invoked the Monroe Doctrine and said that these are called “Donroe Doctrine,” signaling that the Western Hemisphere remains a zone of US dominion—an assertion clearly made in the National Security Strategy launched in November 2025. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s subsequent clarification that the US would merely extract policy changes and oil access did nothing to soften the nakedness of the imperial project.

This represents what we at the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research have identified as “hyper-imperialism,” a dangerous and decadent stage of imperialism. Facing the erosion of its economic and political dominance and the rise of alternative centers of power (mainly in Asia) US imperialism increasingly relies on its uncontested military strength. The Chatham House analysis is unequivocal: This constitutes a significant violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the United Nations Charter. There was no Security Council mandate, nor any claims to self-defense.

The post-1945 international order established the formal principle that states possess sovereign equality and that force against another state’s territorial integrity is prohibited. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter was designed precisely to prevent the powerful from treating the world as their domain, which the US has now blatantly ignored.

The Test for Global South Solidarity

The kidnapping of President Maduro poses an existential question to the discourse of “multipolarity.” While the seeds of a multipolar world order may exist (China’s economic rise, the increasing political assertiveness of Global South countries, BRICS and its expansion, the increasing trade in local currencies) they have proven to be extremely limited in the face of the US unilateral use of force. This is an uncomfortable truth.

The initial responses from governments suggest the difficulty of moving from rhetorical condemnation to material constraint. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva correctly identified the stakes when he condemned the capture as crossing “an unacceptable line” and warned that “attacking countries, in flagrant violation of international law, is the first step toward a world of violence, chaos, and instability.” Colombian President Gustavo Petro rejected “the aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and of Latin America.” Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum declared that “the Americas do not belong to any doctrine or any power.” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi condemned US military intervention and called for the release of President Maduro, saying, “We don’t believe that any country can act as the world’s police.”

The groundswell of opposition confronts a structural problem: The institutions designed to prevent such actions are incapable of constraining the permanent members of the Security Council. The United States can veto any resolution condemning its behavior. The emergency Security Council meeting convened at the request of Venezuela and Colombia produced denunciations but no enforcement mechanism.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them. Trump’s threats against Cuba and Colombia underscore this point.

Sovereignty, Resources, and the Right to Self-Determination

The pattern is well established with the successive overthrowing of heads of states when they tried to implement land reform like Árbenz in Guatemala, nationalize national resources under Salvador Allende in Chile and Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran. The thread continues to the present situation in Venezuela.

While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist.

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion barrels. Trump made no effort to disguise the centrality of oil, announcing that American companies would rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry and the US would be “selling oil, probably in much larger doses.” The maritime blockade preceding the military operation served the explicit purpose of strangling the country economically.

Yet the entire trajectory of the US Venezuela policy since 2001, from funding opposition groups to the 2002 coup attempt, to Operation Gideon in 2020, to the “maximum pressure” sanctions, has been designed to prevent Venezuela from making free choices. The assault accelerated after Venezuela enacted its 2001 Hydrocarbons Law asserting sovereign control over oil resources.

Conclusion

The kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and National Assembly deputy Cilia Flores should compel a fundamental reassessment of the state of the international order. The formal institutions and legal frameworks that were supposed to prevent great power aggression have failed to constrain Washington’s imperialist aggressions. This places an enormous responsibility on the governments and peoples of the Global South. The debates around multipolarity, BRICS, South-South cooperation, and de-dollarization are rendered academic if they do not translate into the practical capacity to impose costs on actions like the invasion of Venezuela. Ultimately, the imperialist aggression against Venezuela has repercussions for governments and peoples around the world, regardless of their ideological orientation or views on the Maduro government. While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist. The defense of Venezuelan people’s sovereignty, after all, is a defense of the sovereignty of all our nations.

- Venezuela’s Oil, US-led Regime Change, and America’s Gangster Politics ›

- 'This Is State Terrorism': Global Outrage as Trump Launches Illegal Assault on Venezuela ›

- It Was Trump, Not America: The Criminal Abduction of Venezuela’s President ›

- After Venezuela Assault, Trump and Rubio Warn Cuba, Mexico, and Colombia Could Be Next ›

- More Countries Condemn Trump's 'Imperialist' Saber-Rattling Against Venezuela ›

On January 3, 2026, the United States did not merely bomb a sovereign country and capture its president. It displayed, in the most unambiguous terms, a total defiance of the post-war international order that it helped create. When US special forces captured Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife and National Assembly Deputy Cilia Flores from Caracas and transported them to a Brooklyn jail, they did not simply violate Venezuelan sovereignty. They declared that sovereignty itself, for any nation that refuses subordination to US imperialism, holds no weight.

As Nicolás Maduro Guerra, the president’s son, stated before Venezuela’s National Assembly: “If we normalize the kidnapping of a head of state, no country is safe. Today it’s Venezuela. Tomorrow, it could be any nation that refuses to submit.”

The response to this act, regardless of one’s political orientation or views on the Maduro government, will determine whether the concepts of international law, multilateralism, and the self-determination of peoples retain any meaning in the 21st century. This is not a question for the left alone. It is a question for every nation, every government, and every citizen who believes that the world should not be governed by the principle that might makes right.

The Logic of Hyper-Imperialism Unveiled

What distinguishes the current phase of US foreign policy from earlier periods of intervention is its brazenness. When the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of Guatemalan President Jacobo Árbenz in 1954, Washington maintained the pretense of responding to communist subversion. When American forces invaded Panama in 1989 to capture Manuel Noriega, the justification was framed within a discourse of law enforcement. The history of US intervention in Latin America spans over 40 successful regime changes in slightly less than a century, according to Harvard scholar John Coatsworth.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them.

But President Donald Trump’s announcement that the United States would “run” Venezuela represents something qualitatively different. Here there is no pretense. When asked about the operation, Trump invoked the Monroe Doctrine and said that these are called “Donroe Doctrine,” signaling that the Western Hemisphere remains a zone of US dominion—an assertion clearly made in the National Security Strategy launched in November 2025. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s subsequent clarification that the US would merely extract policy changes and oil access did nothing to soften the nakedness of the imperial project.

This represents what we at the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research have identified as “hyper-imperialism,” a dangerous and decadent stage of imperialism. Facing the erosion of its economic and political dominance and the rise of alternative centers of power (mainly in Asia) US imperialism increasingly relies on its uncontested military strength. The Chatham House analysis is unequivocal: This constitutes a significant violation of Venezuelan sovereignty and the United Nations Charter. There was no Security Council mandate, nor any claims to self-defense.

The post-1945 international order established the formal principle that states possess sovereign equality and that force against another state’s territorial integrity is prohibited. Article 2(4) of the UN Charter was designed precisely to prevent the powerful from treating the world as their domain, which the US has now blatantly ignored.

The Test for Global South Solidarity

The kidnapping of President Maduro poses an existential question to the discourse of “multipolarity.” While the seeds of a multipolar world order may exist (China’s economic rise, the increasing political assertiveness of Global South countries, BRICS and its expansion, the increasing trade in local currencies) they have proven to be extremely limited in the face of the US unilateral use of force. This is an uncomfortable truth.

The initial responses from governments suggest the difficulty of moving from rhetorical condemnation to material constraint. Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula Da Silva correctly identified the stakes when he condemned the capture as crossing “an unacceptable line” and warned that “attacking countries, in flagrant violation of international law, is the first step toward a world of violence, chaos, and instability.” Colombian President Gustavo Petro rejected “the aggression against the sovereignty of Venezuela and of Latin America.” Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum declared that “the Americas do not belong to any doctrine or any power.” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi condemned US military intervention and called for the release of President Maduro, saying, “We don’t believe that any country can act as the world’s police.”

The groundswell of opposition confronts a structural problem: The institutions designed to prevent such actions are incapable of constraining the permanent members of the Security Council. The United States can veto any resolution condemning its behavior. The emergency Security Council meeting convened at the request of Venezuela and Colombia produced denunciations but no enforcement mechanism.

Every government that has sought to develop independently, that has attempted to control its own natural resources, that has resisted subordination to Washington, must recognize that what has happened in Venezuela could happen to them. Trump’s threats against Cuba and Colombia underscore this point.

Sovereignty, Resources, and the Right to Self-Determination

The pattern is well established with the successive overthrowing of heads of states when they tried to implement land reform like Árbenz in Guatemala, nationalize national resources under Salvador Allende in Chile and Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran. The thread continues to the present situation in Venezuela.

While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist.

Venezuela possesses the world’s largest proven oil reserves, estimated at 303 billion barrels. Trump made no effort to disguise the centrality of oil, announcing that American companies would rebuild Venezuela’s oil industry and the US would be “selling oil, probably in much larger doses.” The maritime blockade preceding the military operation served the explicit purpose of strangling the country economically.

Yet the entire trajectory of the US Venezuela policy since 2001, from funding opposition groups to the 2002 coup attempt, to Operation Gideon in 2020, to the “maximum pressure” sanctions, has been designed to prevent Venezuela from making free choices. The assault accelerated after Venezuela enacted its 2001 Hydrocarbons Law asserting sovereign control over oil resources.

Conclusion

The kidnapping of Nicolás Maduro and National Assembly deputy Cilia Flores should compel a fundamental reassessment of the state of the international order. The formal institutions and legal frameworks that were supposed to prevent great power aggression have failed to constrain Washington’s imperialist aggressions. This places an enormous responsibility on the governments and peoples of the Global South. The debates around multipolarity, BRICS, South-South cooperation, and de-dollarization are rendered academic if they do not translate into the practical capacity to impose costs on actions like the invasion of Venezuela. Ultimately, the imperialist aggression against Venezuela has repercussions for governments and peoples around the world, regardless of their ideological orientation or views on the Maduro government. While the real limits of “multipolarity” in this stage of US hyper-imperialism have been laid bare, we must continue building our collective capacity to resist. The defense of Venezuelan people’s sovereignty, after all, is a defense of the sovereignty of all our nations.

- Venezuela’s Oil, US-led Regime Change, and America’s Gangster Politics ›

- 'This Is State Terrorism': Global Outrage as Trump Launches Illegal Assault on Venezuela ›

- It Was Trump, Not America: The Criminal Abduction of Venezuela’s President ›

- After Venezuela Assault, Trump and Rubio Warn Cuba, Mexico, and Colombia Could Be Next ›

- More Countries Condemn Trump's 'Imperialist' Saber-Rattling Against Venezuela ›