SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

Carbon farming on an organic farm. (Photo: Elizabeth Henderson)

In February, a dairy farmer friend sent me a note confiding that a few farmers she knows are living on cereal until their milk checks arrive. Yet, the recently released census of agriculture shows that the number of young farmers is growing even as the average age of farmers also increases, and there are uplifting articles about young Black farmers connecting with the land and enjoying the self-empowerment that comes with being an independent farmer.

Meanwhile, voices are rising about the central role that regenerative and organic farming can play in a Green New Deal, a program to mobilize all possible forces to prevent climate disaster.

How can we make sense of these conflicting currents? What policies and programs will create a just transition for family-scale farmers? What changes will enable farmers to maximize the potential of photosynthesis for putting carbon in the soil to supplement reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in mitigating climate disaster?

Farmers who are constantly worrying about financial viability have little bandwidth for new practices or long-term improvements that take initial investments. As Robert Leonard and Matt Russell noted in an opinion piece in the New York Times:

"Government programs like the current farm bill pit production against conservation, and doing the right thing for the environment is a considerable drain on a farmer's bank account, especially when so many of them are losing money to low commodity prices and President Trump's tariffs."

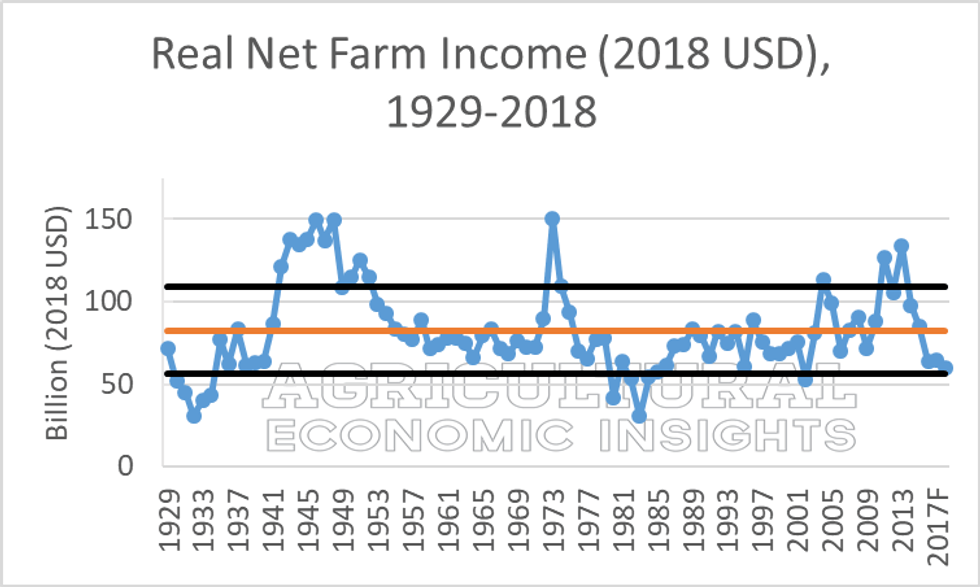

The farm debt crisis of the 1980s never completely went away and has now resurfaced with a vengeance. In 2017, aggregate farm earnings were half of what they were in 2013 due to vast overproduction of basic commodities, and farm income has not recovered. The North American Free Trade Agreement resulted in the loss of mid-sized and smaller farms in all three signatory countries as integrated production and marketing favored larger farms.

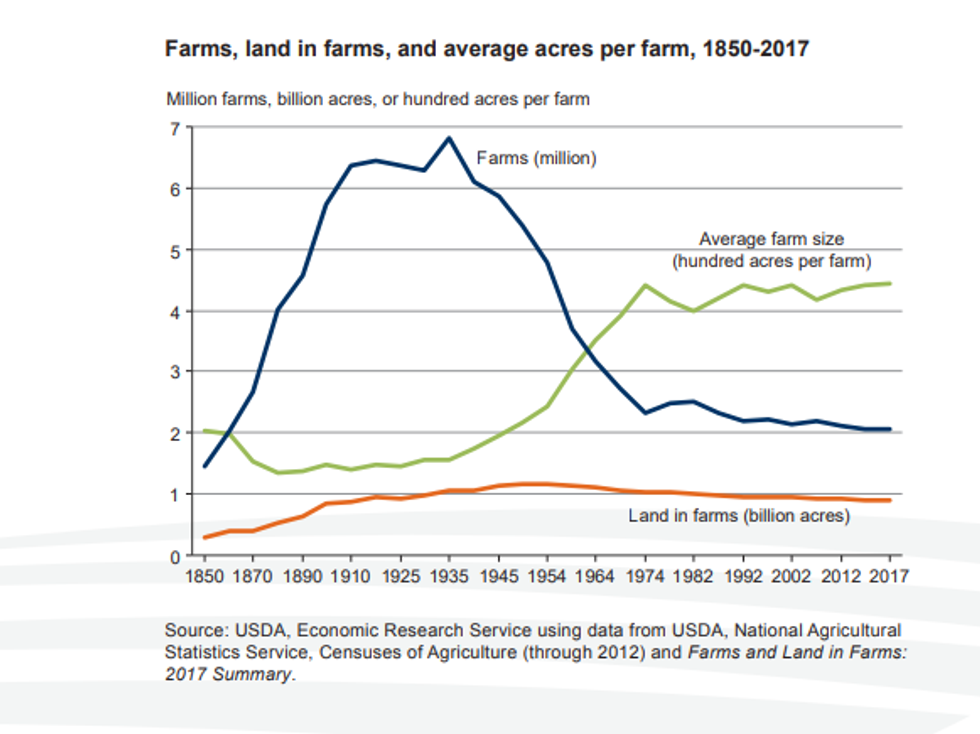

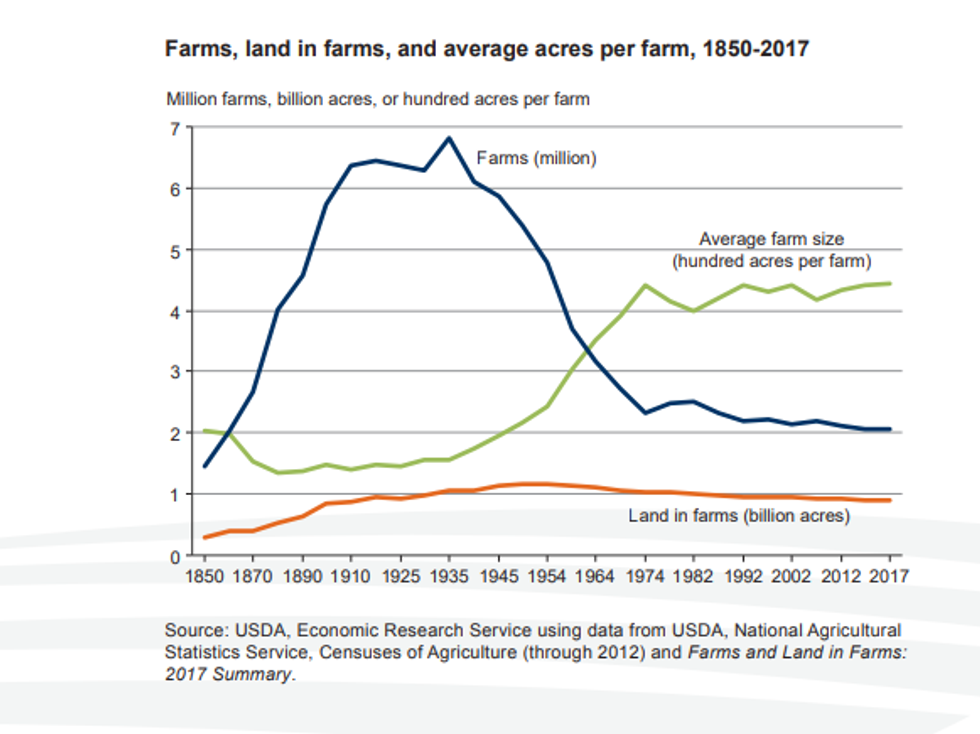

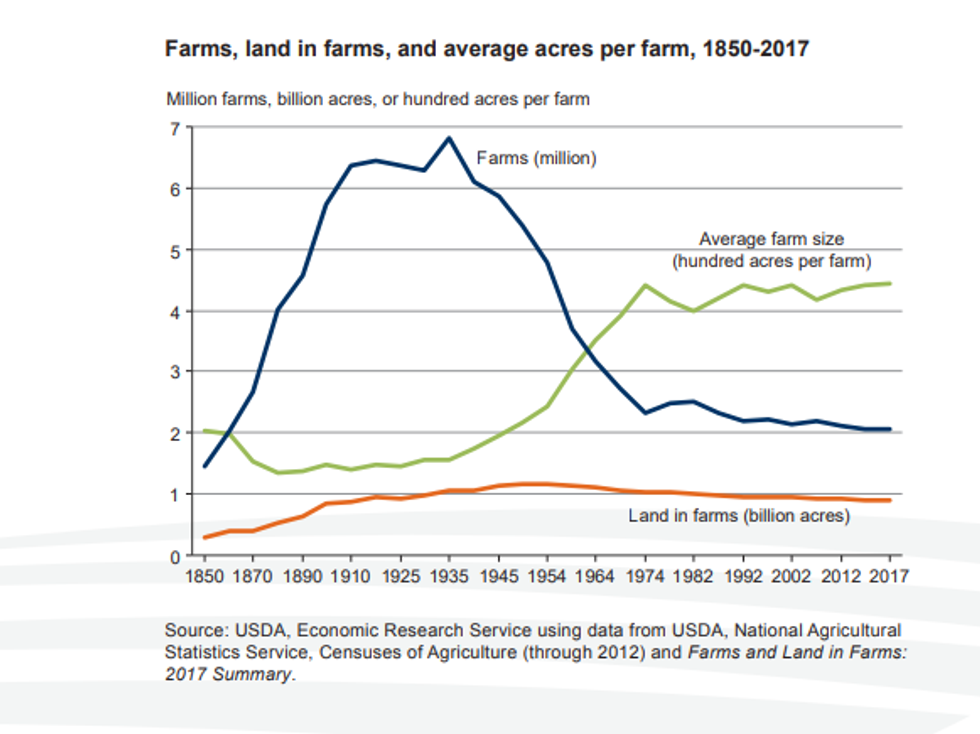

Since 1950, the U.S. has gone from 5.4 million farms to just over 2 million, a loss of more than 3 million farms, with important shifts from many smaller integrated farms to fewer large, more specialized farms that grow even larger. For dairy farms in particular, these have been hard times as illustrated by the losses in the two top dairy states. New York State has lost 20 percent of its dairy farms in the past five years. Wisconsin lost 691 dairy farms in 2018.

While the persistence and shrewd maneuvering of organizations like the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and the National Organic Coalition meant that programs that support organic and sustainable farming fared remarkably well in the 2018 Farm Bill, the bulk of the more than 500-page bill carries on with business as usual, even making it easier for big farms to get bigger by failing to cap the payments any one farm can receive and allowing more relatives to cash in on programs in the bill.

Both mainstream parties advocate the neoliberal, free-trade policies that the ever more aggregated seed, food and chemical corporations have imposed upon the U.S. since World War II to the detriment of family-scale farms all over the world. The dairy farmers who got through the winter eating cereal and the new farmers who are eagerly starting out are in urgent need of radical change.

Why is this happening? Political economist and author Eric Holt Gimenez would say this is just capitalism working as it is supposed to. Faced with slim margins in the race to cover farm expenses, farmers produce more, and that drives prices down even further. The beneficiaries are the ever-larger corporations that have consolidated their dominance in the food sector. The result? Shoppers pay more, and a shrinking portion of what they pay goes to farmers.

At first, this mainly hit conventional farms; then in 2017, organic processors started limiting the amount of milk they purchased from organic dairies and cut the price paid below the cost of production. As a result, family-scale farms of all kinds are going out of business, and tragically, there are increasing reports of farmer suicides.

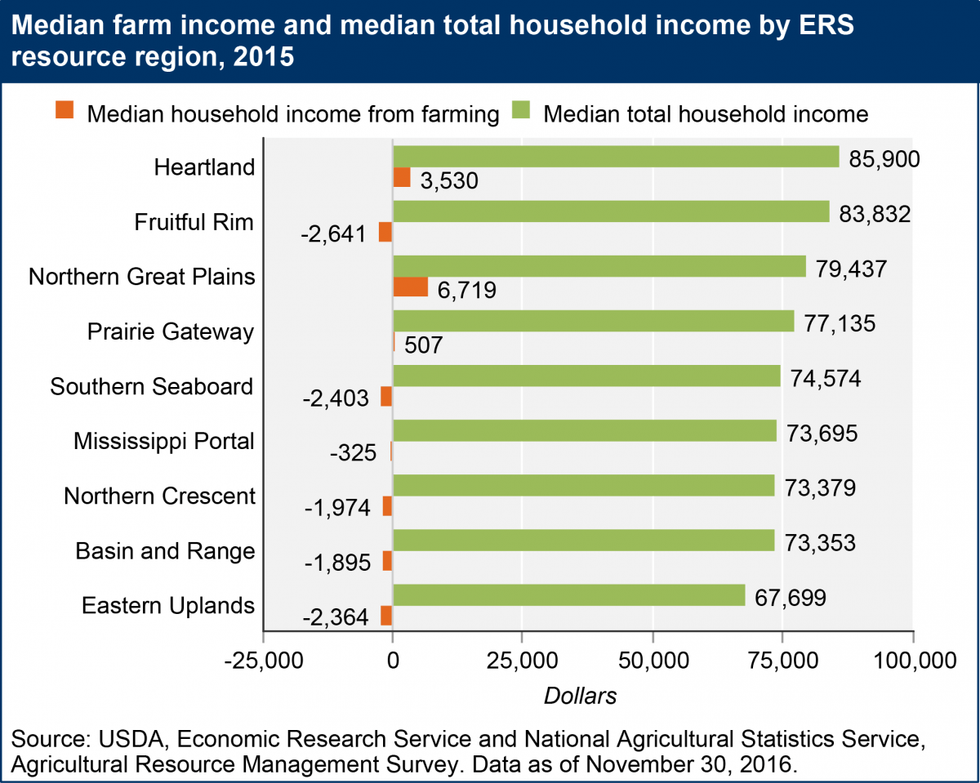

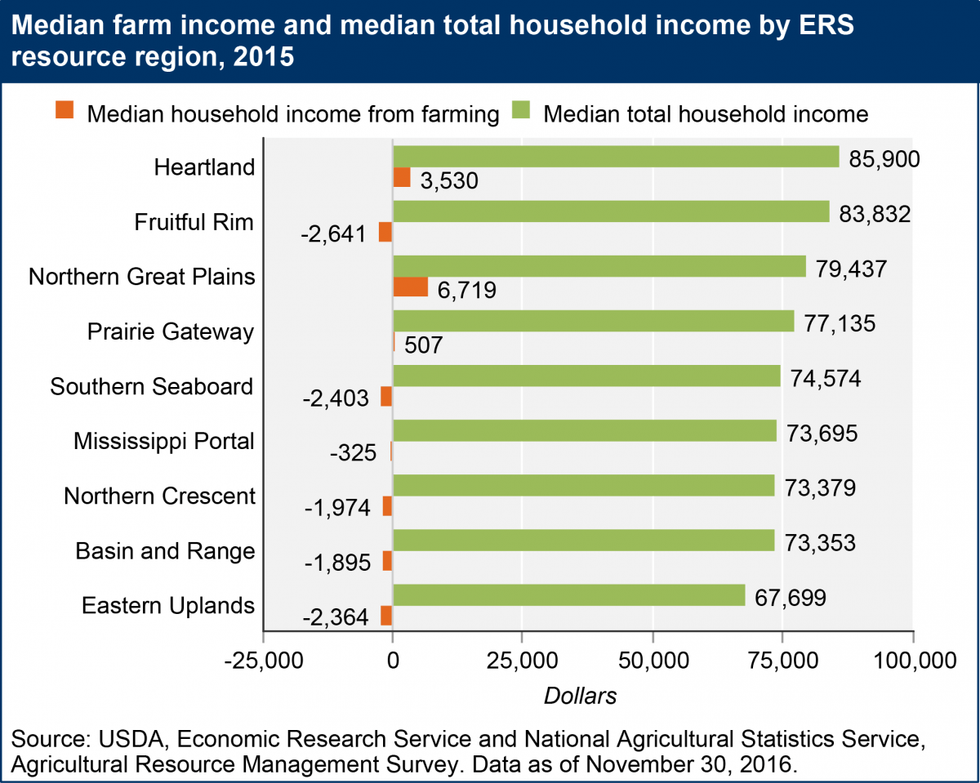

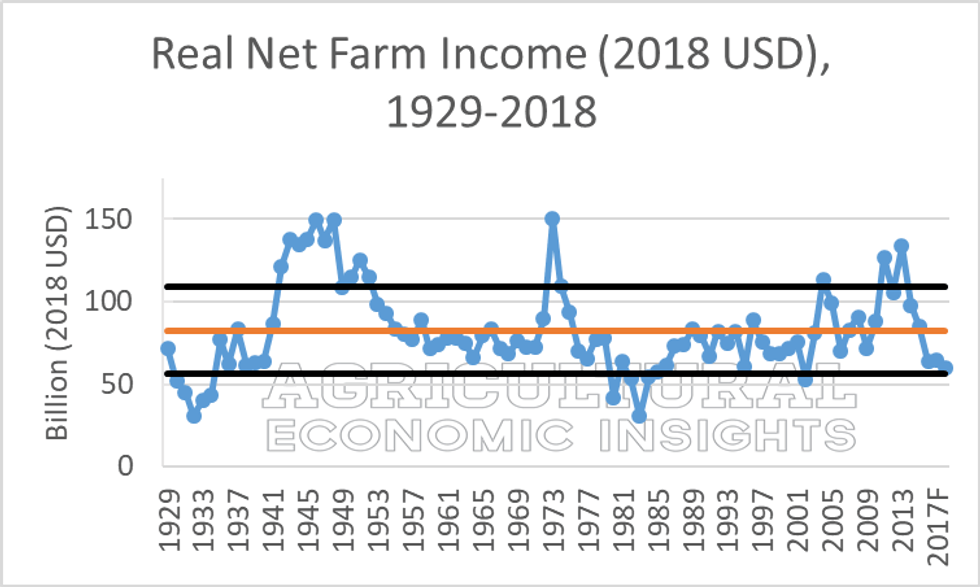

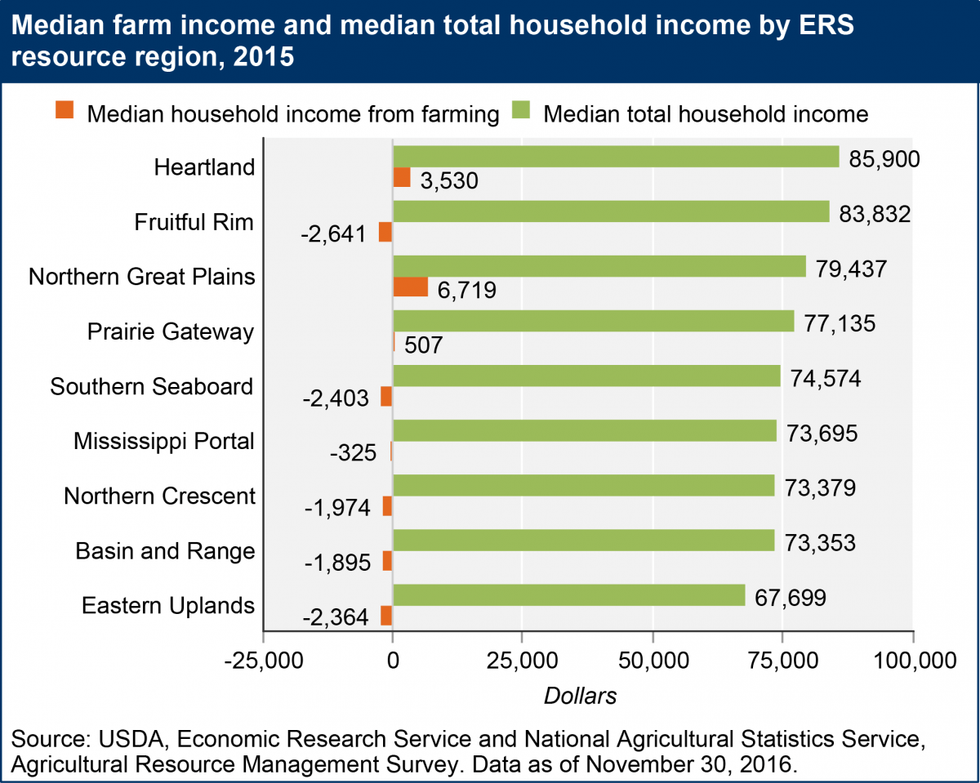

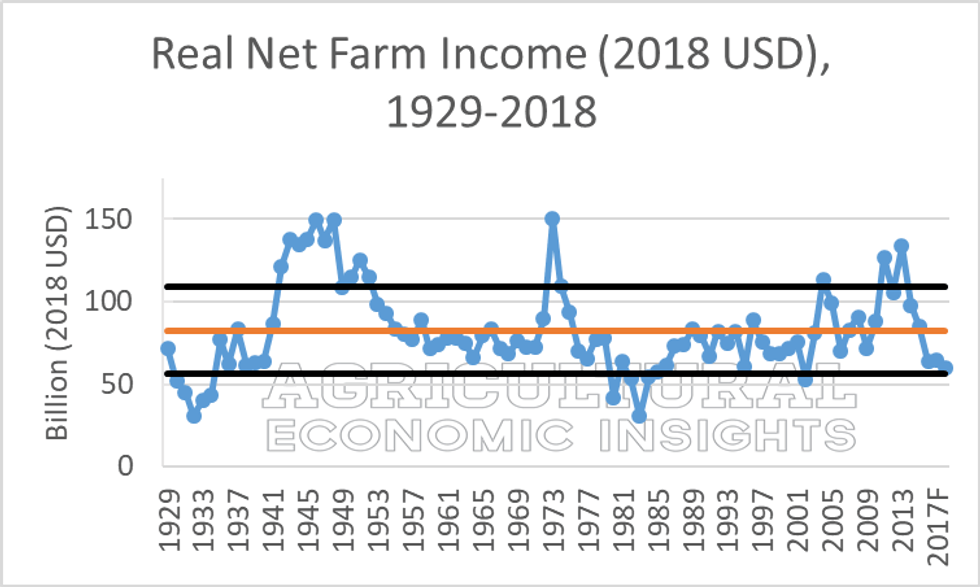

If you juxtapose the Agricultural Economic Insights chart with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) chart above showing the declining number of farms, it is clear that loss of farm income corresponds with the loss of farms. More than half of U.S. farm households lost money farming in recent years, according to the USDA, which estimated that median farm income for U.S. farm households was negative $1,553 in 2018.

Farm incomes have dropped despite record productivity on U.S. farms because oversupply drives down commodity prices. Through a plethora of racist policies, Black farmers have lost land at more than five times the rate of white farmers from the peak of Black farmland ownership in 1910 until the 1990s. Meanwhile, profits in consolidated food businesses (farm inputs, retail stores) remain high with returns on investment ranging from 8 to 35 percent. Clearly, there is plenty of money in food: It just does not get apportioned fairly to the people who do the actual work.

Programs to train new farmers, especially veterans, get media attention and funding, but as the National Young Farmers Coalition repeats tirelessly, land in most parts of the country is too expensive for a farmer to buy with farm earnings. USDA data show that farm families have a middle-class income, but only on the largest farms growing a few commodities is that income from farm earnings.

So, while presidential candidates and Green New Dealers are putting bold proposals on the table for public discourse, farmers, farmworkers and concerned eaters should take the opportunity to hammer out proposals that will solve the structural issues that have turned U.S. farming into a problem instead of the win-win-win solutions that are possible.

Declaring that she wants "Washington to work for family farmers again," Sen. Elizabeth Warren promises to take some steps in the right direction by breaking up vertically integrated trusts, allowing farmers themselves to repair the equipment they purchase, ensuring that contracts for livestock farmers are fair, reinvigorating country of origin labeling, and restricting foreign ownership of farmland.

Sen. Bernie Sanders goes much further, outlining a program that would completely restructure the food system so that farmers can make a living and afford to pay living wages to employees. These are the policies this country needs if we hope to keep family-scale farming.

When farmers can afford to adopt regenerative organic practices, they will take more carbon out of the air and put it in the soil where it builds soil health, making the people and livestock who eat those crops healthier. The original New Deal's parity pricing also fueled the soil conservation that ended the dust bowl.

Farmers can focus on carbon farming if the price they receive in the marketplace covers the costs of running their farms. Family-scale farmers and the people who want to eat locally grown food all need a fair Green New Deal for the 21st century.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute, and originally published by Truthout.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In February, a dairy farmer friend sent me a note confiding that a few farmers she knows are living on cereal until their milk checks arrive. Yet, the recently released census of agriculture shows that the number of young farmers is growing even as the average age of farmers also increases, and there are uplifting articles about young Black farmers connecting with the land and enjoying the self-empowerment that comes with being an independent farmer.

Meanwhile, voices are rising about the central role that regenerative and organic farming can play in a Green New Deal, a program to mobilize all possible forces to prevent climate disaster.

How can we make sense of these conflicting currents? What policies and programs will create a just transition for family-scale farmers? What changes will enable farmers to maximize the potential of photosynthesis for putting carbon in the soil to supplement reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in mitigating climate disaster?

Farmers who are constantly worrying about financial viability have little bandwidth for new practices or long-term improvements that take initial investments. As Robert Leonard and Matt Russell noted in an opinion piece in the New York Times:

"Government programs like the current farm bill pit production against conservation, and doing the right thing for the environment is a considerable drain on a farmer's bank account, especially when so many of them are losing money to low commodity prices and President Trump's tariffs."

The farm debt crisis of the 1980s never completely went away and has now resurfaced with a vengeance. In 2017, aggregate farm earnings were half of what they were in 2013 due to vast overproduction of basic commodities, and farm income has not recovered. The North American Free Trade Agreement resulted in the loss of mid-sized and smaller farms in all three signatory countries as integrated production and marketing favored larger farms.

Since 1950, the U.S. has gone from 5.4 million farms to just over 2 million, a loss of more than 3 million farms, with important shifts from many smaller integrated farms to fewer large, more specialized farms that grow even larger. For dairy farms in particular, these have been hard times as illustrated by the losses in the two top dairy states. New York State has lost 20 percent of its dairy farms in the past five years. Wisconsin lost 691 dairy farms in 2018.

While the persistence and shrewd maneuvering of organizations like the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and the National Organic Coalition meant that programs that support organic and sustainable farming fared remarkably well in the 2018 Farm Bill, the bulk of the more than 500-page bill carries on with business as usual, even making it easier for big farms to get bigger by failing to cap the payments any one farm can receive and allowing more relatives to cash in on programs in the bill.

Both mainstream parties advocate the neoliberal, free-trade policies that the ever more aggregated seed, food and chemical corporations have imposed upon the U.S. since World War II to the detriment of family-scale farms all over the world. The dairy farmers who got through the winter eating cereal and the new farmers who are eagerly starting out are in urgent need of radical change.

Why is this happening? Political economist and author Eric Holt Gimenez would say this is just capitalism working as it is supposed to. Faced with slim margins in the race to cover farm expenses, farmers produce more, and that drives prices down even further. The beneficiaries are the ever-larger corporations that have consolidated their dominance in the food sector. The result? Shoppers pay more, and a shrinking portion of what they pay goes to farmers.

At first, this mainly hit conventional farms; then in 2017, organic processors started limiting the amount of milk they purchased from organic dairies and cut the price paid below the cost of production. As a result, family-scale farms of all kinds are going out of business, and tragically, there are increasing reports of farmer suicides.

If you juxtapose the Agricultural Economic Insights chart with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) chart above showing the declining number of farms, it is clear that loss of farm income corresponds with the loss of farms. More than half of U.S. farm households lost money farming in recent years, according to the USDA, which estimated that median farm income for U.S. farm households was negative $1,553 in 2018.

Farm incomes have dropped despite record productivity on U.S. farms because oversupply drives down commodity prices. Through a plethora of racist policies, Black farmers have lost land at more than five times the rate of white farmers from the peak of Black farmland ownership in 1910 until the 1990s. Meanwhile, profits in consolidated food businesses (farm inputs, retail stores) remain high with returns on investment ranging from 8 to 35 percent. Clearly, there is plenty of money in food: It just does not get apportioned fairly to the people who do the actual work.

Programs to train new farmers, especially veterans, get media attention and funding, but as the National Young Farmers Coalition repeats tirelessly, land in most parts of the country is too expensive for a farmer to buy with farm earnings. USDA data show that farm families have a middle-class income, but only on the largest farms growing a few commodities is that income from farm earnings.

So, while presidential candidates and Green New Dealers are putting bold proposals on the table for public discourse, farmers, farmworkers and concerned eaters should take the opportunity to hammer out proposals that will solve the structural issues that have turned U.S. farming into a problem instead of the win-win-win solutions that are possible.

Declaring that she wants "Washington to work for family farmers again," Sen. Elizabeth Warren promises to take some steps in the right direction by breaking up vertically integrated trusts, allowing farmers themselves to repair the equipment they purchase, ensuring that contracts for livestock farmers are fair, reinvigorating country of origin labeling, and restricting foreign ownership of farmland.

Sen. Bernie Sanders goes much further, outlining a program that would completely restructure the food system so that farmers can make a living and afford to pay living wages to employees. These are the policies this country needs if we hope to keep family-scale farming.

When farmers can afford to adopt regenerative organic practices, they will take more carbon out of the air and put it in the soil where it builds soil health, making the people and livestock who eat those crops healthier. The original New Deal's parity pricing also fueled the soil conservation that ended the dust bowl.

Farmers can focus on carbon farming if the price they receive in the marketplace covers the costs of running their farms. Family-scale farmers and the people who want to eat locally grown food all need a fair Green New Deal for the 21st century.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute, and originally published by Truthout.

In February, a dairy farmer friend sent me a note confiding that a few farmers she knows are living on cereal until their milk checks arrive. Yet, the recently released census of agriculture shows that the number of young farmers is growing even as the average age of farmers also increases, and there are uplifting articles about young Black farmers connecting with the land and enjoying the self-empowerment that comes with being an independent farmer.

Meanwhile, voices are rising about the central role that regenerative and organic farming can play in a Green New Deal, a program to mobilize all possible forces to prevent climate disaster.

How can we make sense of these conflicting currents? What policies and programs will create a just transition for family-scale farmers? What changes will enable farmers to maximize the potential of photosynthesis for putting carbon in the soil to supplement reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in mitigating climate disaster?

Farmers who are constantly worrying about financial viability have little bandwidth for new practices or long-term improvements that take initial investments. As Robert Leonard and Matt Russell noted in an opinion piece in the New York Times:

"Government programs like the current farm bill pit production against conservation, and doing the right thing for the environment is a considerable drain on a farmer's bank account, especially when so many of them are losing money to low commodity prices and President Trump's tariffs."

The farm debt crisis of the 1980s never completely went away and has now resurfaced with a vengeance. In 2017, aggregate farm earnings were half of what they were in 2013 due to vast overproduction of basic commodities, and farm income has not recovered. The North American Free Trade Agreement resulted in the loss of mid-sized and smaller farms in all three signatory countries as integrated production and marketing favored larger farms.

Since 1950, the U.S. has gone from 5.4 million farms to just over 2 million, a loss of more than 3 million farms, with important shifts from many smaller integrated farms to fewer large, more specialized farms that grow even larger. For dairy farms in particular, these have been hard times as illustrated by the losses in the two top dairy states. New York State has lost 20 percent of its dairy farms in the past five years. Wisconsin lost 691 dairy farms in 2018.

While the persistence and shrewd maneuvering of organizations like the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition and the National Organic Coalition meant that programs that support organic and sustainable farming fared remarkably well in the 2018 Farm Bill, the bulk of the more than 500-page bill carries on with business as usual, even making it easier for big farms to get bigger by failing to cap the payments any one farm can receive and allowing more relatives to cash in on programs in the bill.

Both mainstream parties advocate the neoliberal, free-trade policies that the ever more aggregated seed, food and chemical corporations have imposed upon the U.S. since World War II to the detriment of family-scale farms all over the world. The dairy farmers who got through the winter eating cereal and the new farmers who are eagerly starting out are in urgent need of radical change.

Why is this happening? Political economist and author Eric Holt Gimenez would say this is just capitalism working as it is supposed to. Faced with slim margins in the race to cover farm expenses, farmers produce more, and that drives prices down even further. The beneficiaries are the ever-larger corporations that have consolidated their dominance in the food sector. The result? Shoppers pay more, and a shrinking portion of what they pay goes to farmers.

At first, this mainly hit conventional farms; then in 2017, organic processors started limiting the amount of milk they purchased from organic dairies and cut the price paid below the cost of production. As a result, family-scale farms of all kinds are going out of business, and tragically, there are increasing reports of farmer suicides.

If you juxtapose the Agricultural Economic Insights chart with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) chart above showing the declining number of farms, it is clear that loss of farm income corresponds with the loss of farms. More than half of U.S. farm households lost money farming in recent years, according to the USDA, which estimated that median farm income for U.S. farm households was negative $1,553 in 2018.

Farm incomes have dropped despite record productivity on U.S. farms because oversupply drives down commodity prices. Through a plethora of racist policies, Black farmers have lost land at more than five times the rate of white farmers from the peak of Black farmland ownership in 1910 until the 1990s. Meanwhile, profits in consolidated food businesses (farm inputs, retail stores) remain high with returns on investment ranging from 8 to 35 percent. Clearly, there is plenty of money in food: It just does not get apportioned fairly to the people who do the actual work.

Programs to train new farmers, especially veterans, get media attention and funding, but as the National Young Farmers Coalition repeats tirelessly, land in most parts of the country is too expensive for a farmer to buy with farm earnings. USDA data show that farm families have a middle-class income, but only on the largest farms growing a few commodities is that income from farm earnings.

So, while presidential candidates and Green New Dealers are putting bold proposals on the table for public discourse, farmers, farmworkers and concerned eaters should take the opportunity to hammer out proposals that will solve the structural issues that have turned U.S. farming into a problem instead of the win-win-win solutions that are possible.

Declaring that she wants "Washington to work for family farmers again," Sen. Elizabeth Warren promises to take some steps in the right direction by breaking up vertically integrated trusts, allowing farmers themselves to repair the equipment they purchase, ensuring that contracts for livestock farmers are fair, reinvigorating country of origin labeling, and restricting foreign ownership of farmland.

Sen. Bernie Sanders goes much further, outlining a program that would completely restructure the food system so that farmers can make a living and afford to pay living wages to employees. These are the policies this country needs if we hope to keep family-scale farming.

When farmers can afford to adopt regenerative organic practices, they will take more carbon out of the air and put it in the soil where it builds soil health, making the people and livestock who eat those crops healthier. The original New Deal's parity pricing also fueled the soil conservation that ended the dust bowl.

Farmers can focus on carbon farming if the price they receive in the marketplace covers the costs of running their farms. Family-scale farmers and the people who want to eat locally grown food all need a fair Green New Deal for the 21st century.

This article was produced by Earth | Food | Life, a project of the Independent Media Institute, and originally published by Truthout.