SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

There is a truth that many of those who think themselves untouched by war are unable or unwilling to understand. War never goes away.

Not long ago, I received a Facebook "friend" request from Jean, an individual I had known in grammar school. It was nice to hear from her, that she was in good health, and doing well. Over the subsequent weeks, we exchanged pleasantries, read each other's posts, and caught up somewhat with how our lives had progressed over the past 50 or so years.

The pleasantries were rather short-lived, however, as Jean rather quickly became disenchanted, perhaps annoyed is more accurate, with my "preoccupation" with politics, social issues, and the "fact" that my Facebook commentaries and analyses—"rants" she called them—were, in her opinion, "unhealthy, self-destructive, and downright anti-American." She expressed what I took to be a heartfelt concern for my well-being, that I was such a sad and angry man, unhappy with my life and my country, and obsessed with a war some 50 years gone. She knew I had been a Marine in Vietnam, had heard over the years that I had been affected by the experience, but only now realized the severity of my condition—a Facebook diagnosis.

"As a friend," she counseled me that I should stop with the politics, protests, and dissent, put the war behind me and go on with my life. None of this, of course, was new to me, and, I would guess, to many others who had participated in war. So, I politely thanked her for her concern and advice, and continued with my protests, dissent, and "rants" about politics, issues of social justice, and war.

Not long afterward, however, having grown frustrated, I guess, with my unwillingness to follow her advice and make the necessary "positive" changes in my life, she wished me well. After a final expression of concern for my well-being (she was aware of the 17.6 veterans who committed suicide each day), Jean terminated our interaction, “unfriended me” in Facebook jargon.

She was right, of course, at least about how the war had seriously impacted my life, how I had become both sad and angry. Sad that upon returning home to the "world," I no longer fit in. How I felt alone, alienated from friends and family members and how for the longest time, I was unable to maintain a relationship or keep a normal job. She was right as well about my being angry. Angry about how I felt used by my country, lied to about the necessity and justice of the cause for which so many lives were devastated. Angry that the hopes and dreams I had for my life were never realized, and, most tragic, angry that many of our leaders and fellow citizens learned nothing from the debacle... and we are doing it all again.

She was wrong, however, in her assumption that in a life amidst the chaos and unrest, I hadn't tried to achieve a sense of normalcy and well-being. Damn, I had tried a whole lot. Perhaps Jean was right, however, and my inability to heal was the result of a choice that I made, to recognize and accept responsibility and culpability for the crimes perpetrated upon the Vietnamese people. That I had no right to “come home” when so many others were never afforded the opportunity; the 3.8 million Vietnamese, the 58,281 fellow Americans whose names are inscribed on the Wall of Remembrance in D.C., and the over 50,000 Vietnam Veterans who died by their own hand.

Eventually, I realized a truth that many of those who think themselves untouched by war are unable or unwilling to understand. War never goes away.

Perhaps the best that can be hoped for, I think, is to continue the struggle to accommodate the trauma, the pain, and the suffering (the PTSD); the guilt, the sadness, and the anger (the Moral Injury); and to find a place for it in one’s being. Easier said than done, of course, a Sisyphean task I will struggle with for the rest of my life.

Let's consider everything that was wrong with this article targeting the recent winner of the Democratic primary in the New York City mayoral race. It’s a long list.

The sad fact is that there is nothing terribly out of character about the New York Times’s decision to publish a deceptive hit piece about New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani, based on hacked data supplied by a noted eugenicist to whom they granted anonymity.

The newsroom will go to extreme lengths to achieve its primary missions — and one of them, most assuredly, is to take cheap shots at the left.

You can see it almost daily – just this past week alone in a condescending article about Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s brave defense of democracy, and a celebratory story about Trump’s achievements that likened dissenting views to “asterisks” on his legacy.

Under what other circumstance could a story that breaks so many of the Times’s own rules have won the approval of senior editors?

And you can trace it back to the very top: to editor Joe Kahn and his boss, publisher A.G. Sulzberger. As I’ve exhaustively chronicled in my coverage of the New York Times, the newsroom is constantly under pressure from its leaders to prove that it is not taking sides in politics — or democracy, for that matter. And because printing the truth is seen as punching right, that requires expending a lot of effort to punch left. Punching left becomes the holy grail.

I mean think about it. Under what other circumstance could a story that breaks so many of the Times’s own rules have won the approval of senior editors?

Why else would the Times, which notoriously refuses to respond to critics, have issued a ten-tweet defense of its actions? Why else would Kahn have praised the story in Monday’s morning meeting?

Consider everything that was wrong with the article. It’s a long list.

There’s more about the Mamdani piece in this excellent article by Liam Scott in the Columbia Journalism Review.

Parker Molloy, in her newsletter, points out:

When Times columnist Jamelle Bouie had the temerity to post “i think you should tell readers if your source is a nazi,” he was apparently forced to delete it for violating the paper’s social media guidelines. Think about that for a moment. The Times will protect the anonymity of a white supremacist, but will silence their own Black columnist for accurately identifying him.

And Guardian media columnist Margaret Sullivan , who previously worked as the Times' public editor, concludes that “this made-up scandal” — combined with a nasty pre-election editorial – makes the Times look “like it’s on a crusade against Mamdani.”

The Times did its own self-serving follow-up article here, reporting that its disclosure had “provoked sharply different reactions.”

It also published — in what the New Republic’s Jason Linkins called an attempt to “reverse-engineer a pretext for their Mamdani piece” — a query asking readers what they think of racial categories.

When a Times article sets off an understandable explosion of media criticism, like this article did, the response would ideally come from a public editor, or ombud, whose job is to explain what happened and independently assess whether the Times was at fault or not. There would ideally be some learning.

Parts of the Times operation remain brilliant, most notably its investigative journalism and Cooking. But its coverage of anything remotely political is poisoned by its obsession to prove its neutrality by taking cheap shots at the left.

Sadly, The Times eliminated the position of public editor eight years ago. The publisher at the time said “our followers on social media and our readers across the Internet have come together to collectively serve as a modern watchdog, more vigilant and forceful than one person could ever be.”

So on Saturday, the response came from the Times’s hackish “assistant managing editor for standards and trust” Patrick Healy. To say that he does not inspire trust is an understatement.

Healy, who until May was the deputy opinions editor, drove the Times’s excellent columnist Paul Krugman to quit his job. Prior to that, he led a series of right-leaning citizens panels.

He was the newsroom’s politics editor during the 2020 presidential election, and the unapologetic leader of the paper’s “but her emails” coverage.

In short, he seems to revel in trolling the libs.

In his tweets, Healy focused on the article’s “factual accuracy” and he recognized concerns about how the source was identified. But he refused to engage with the concerns that the article was not newsworthy or that its sourcing was repugnant.

“The ultimate source was Columbia admissions data and Mr. Mamdani, who confirmed our reporting,” Healy wrote defensively.

That he is a rising star at the Times – indeed, said to be among the possible successors to Kahn – tells you everything you need to know about what’s wrong there.

Parts of the Times operation remain brilliant, most notably its investigative journalism and Cooking.

But its coverage of anything remotely political is poisoned by its obsession to prove its neutrality by taking cheap shots at the left, no matter the cost to its obligation to accuracy and fairness.

This piece first appeared on Froomkin's website, Press Watch, and appears at Common Dreams with permission.

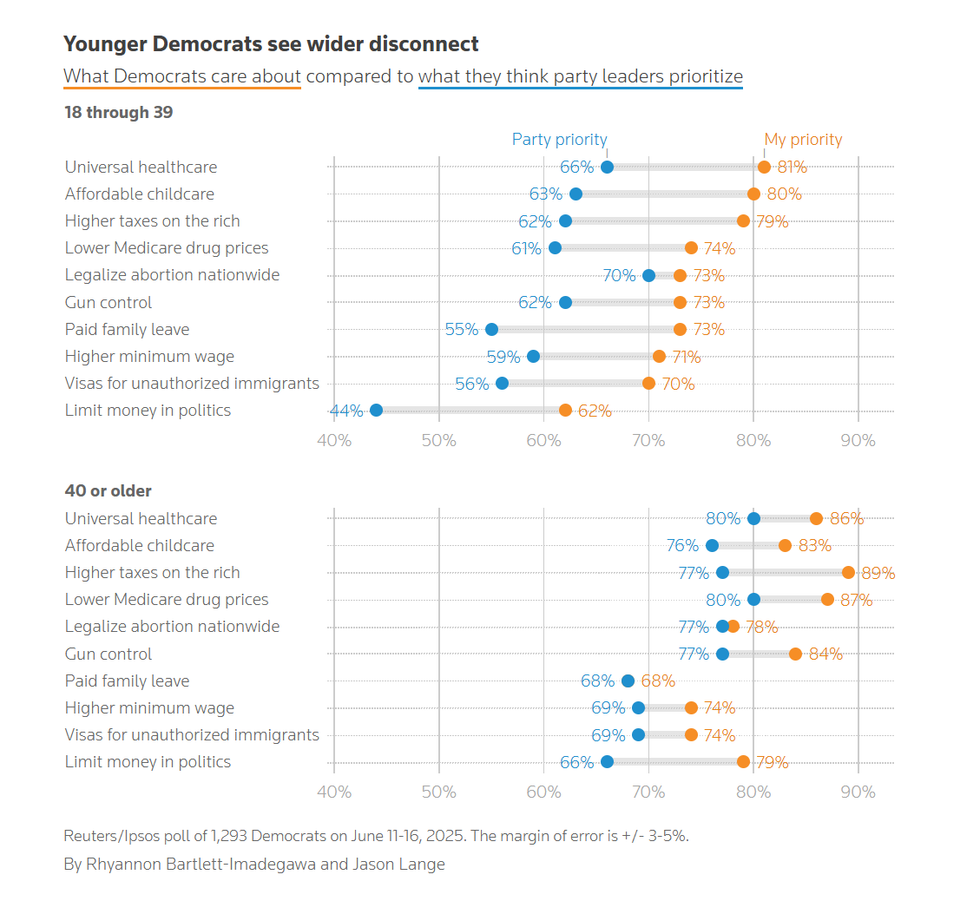

Voters described universal healthcare, affordable childcare, and higher taxes on the rich as top priorities in a new Reuters/Ipsos poll. But they were less likely to believe that party leaders shared those priorities.

Democratic voters want new leadership that will prioritize their day-to-day needs and do more to challenge corporate power, according to a poll published Thursday.

Sixty-two percent of the nearly 1,300 self-identified Democrats who responded to the new Reuters/Ipsos poll agreed with the statement that "the leadership of the Democratic Party should be replaced with new people," while just 24% wanted to keep the old guard around.

The new data delivers another blow to party leaders such as Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.), who have faced growing scrutiny for failing to effectively oppose President Donald Trump in the eyes of their constituents.

The poll, conducted from June 11-16, revealed stark gaps between the agenda Democratic voters would like to see prioritized and what they perceive as party leadership's priorities. Voters overwhelmingly support populist economic policies, according to the data, but doubt that party leaders share those goals—with young voters especially skeptical.

Across all age groups, more than three-quarters of voters described universal healthcare, affordable childcare, and higher taxes on the rich as top priorities. But voters were less likely to believe that party leaders did as well.

Voters between ages 18 to 39 especially had a grim view of leadership. While 81% said they wanted universal healthcare, just 66% said they thought party leadership did too. On limiting money in politics, 62% said it was a priority, compared with just 44% who thought leadership felt the same.

Democrats over 40 were even more inclined to believe in top progressive agenda items. Although they perceived less of a divide between their views and those of party leaders, a significant gap remained.

Following Kamala Harris' defeat in the 2024 election, many corporate-friendly pundits embraced the narrative that voters perceived the Democratic policy agenda as too far left. But the Reuters/Ipsos poll suggests the opposite.

As Sharon Zhang wrote for Truthout, "The majority of federally elected Democrats actually oppose proposals like Medicare for All, and many party leaders have actively worked to sabotage support for such ideas," including Schumer, who declined to support Sen. Bernie Sanders' Medicare for All bill this year.

"Far from taxing the rich," she added, "party leaders have also cozied up to billionaires." Tech giants including Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and Apple all donated millions of dollars to the Harris campaign.

Ben Tulchin, a pollster for Bernie Sanders' 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns, told Reuters that Democratic Party had "room for improvement" on showing Americans that they "are the ones standing up for working people."

"It needs to transform itself into a party that everyday people can get excited about," Tulchin said. "That requires a changing of the guard."