SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

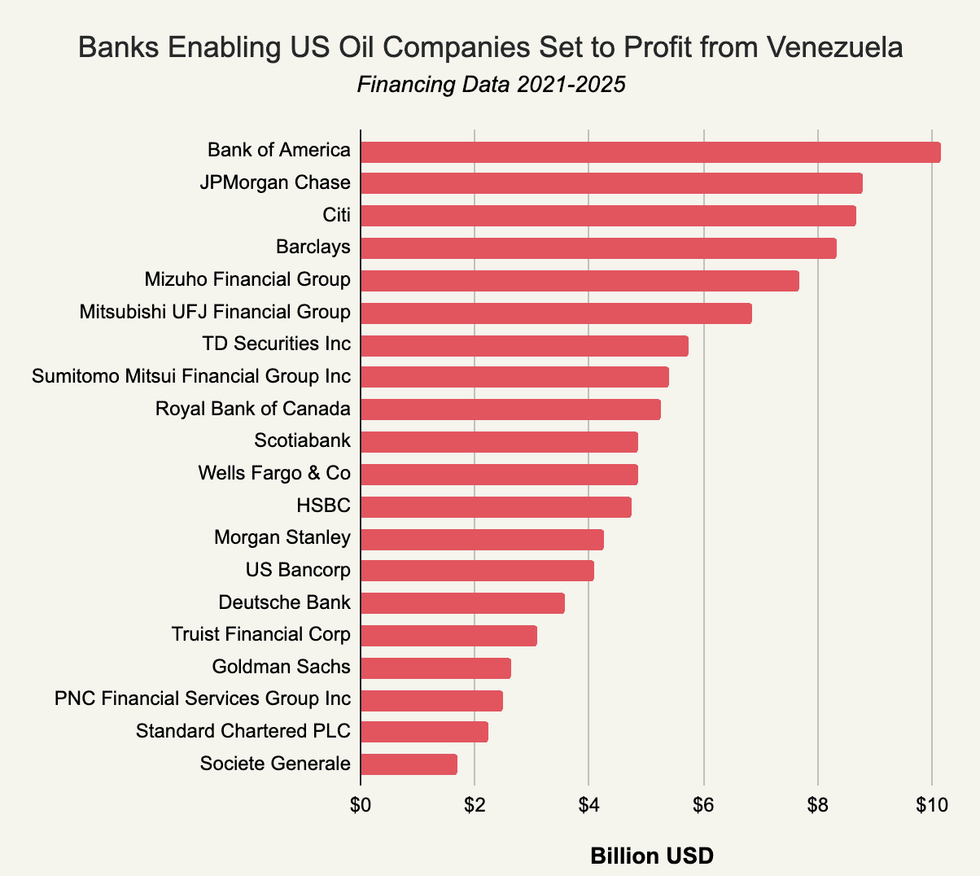

Since 2021, top Wall Street banks have committed more than $124 billion in investments to the nine companies set to profit most from the toppling of Venezuela's government.

As oil industry giants are being set up to profit from President Donald Trump's invasion of Venezuela, a new analysis shows the ample backing those companies have received from Wall Street's top financial institutions.

Last week, Bloomberg reported that stock traders and tycoons were "pouncing" after Trump's kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro earlier this month, after having pressured the Trump administration to "create a more favorable business environment in Venezuela."

A dataset compiled by the international environmental advocacy group Stand.earth shows the extent to which these interests are intertwined.

Stand.earth found that since 2021, banks—including JPMorgan Chase, HSBC, TD, RBC, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America—have committed more than $124 billion in investments to the nine companies set to profit most from the toppling of Venezuela's government.

More than a third of that financing, $42 billion, came in 2025 alone, when Trump launched his aggressive campaign against Venezuela.

Among the companies expected to profit most immediately are refiners like Valero, PBF Energy, Citgo, and Phillips 66, which have large operations on the Gulf Coast that can process the heavy crude Venezuela is known to produce. These four companies have received $41 billion from major banks over the past five years.

Chevron, which also operates many heavy-crude facilities, benefits from being the only US company that operated in Venezuela under the Maduro regime, where it exported more than 140,000 barrels of oil per day last quarter.

At a White House gathering with top oil executives on Friday, the company's vice chair, Mark Nelson, told Trump the company could double its exports "effective immediately."

According to Jason Gabelman, an analyst at TD Cowen, the company could increase its annual cash flow by $400 million to $700 million as a result of Trump's takeover of Venezuelan oil resources.

Chevron was also by far the number-one recipient of investments in 2025, with more than $11 billion in total coming from the banks listed in the report—including $1.78 billion from Barclays, another $1.78 billion from Bank of America, and $1.32 billion from Citigroup.

According to Bloomberg, just weeks before Maduro's removal, analysts at Citigroup predicted 60% gains on the nation's more than $60 billion in bonds if he were replaced.

Even ExxonMobil, whose CEO Darren Woods dumped cold water on Trump's calls to set up operations in Venezuela on Friday, calling the nation "uninvestable," potentially has something major to gain from Maduro's overthrow.

Exxon and ConocoPhillips each have outstanding arbitration cases against Venezuela over the government's 2007 nationalization of oil assets, which could award them $20 billion and $12 billion, respectively.

The report found that in 2025, ExxonMobil and ConocoPhillips received a combined total of more than $12.8 billion in investment from major financial institutions, which vastly exceeded that from previous years.

Data on these staggering investments comes as oil companies face increased scrutiny surrounding possible foreknowledge of Trump's attack on Venezuela.

Last week, US Senate Democrats launched a formal investigation into “communications between major US oil and oilfield services companies and the Trump administration surrounding last week’s military action in Venezuela and efforts to exploit Venezuelan oil resources.”

Richard Brooks, Stand.earth's climate finance director, said the role of the financial institutions underwriting those oil companies should not be overlooked either.

"Without financial support from big banks and investors, the likes of Chevron, Exxon, ConocoPhillips, and Valero would not have the power that they do to start wars, overthrow governments, or slow the pace of climate action," he said. "Banks and investors need to choose if they are on the side of peace, or of warmongering oil companies.”

Public pensions must exit Exxon to protect workers' savings and retirement.

It is no secret that ExxonMobil poses some of the most powerful opposition to climate action at every level of government. Environmentalists have long pointed out that Exxon Knew about climate change, and instead of pivoting their business model to a more sustainable energy future, buried the evidence and began a decades-long disinformation campaign.

Leaders across the country have wisened up to the oil major's dirty politics, which is why the House Oversight Committee has been investigating Exxon and its peers, and state attorneys general have sued the company for damages. Most recently, California AG Rob Bonta, alongside environmental organizations like the Sierra Club, sued the company for lying to the public about the recyclability of plastics.

If the tide is turning against Exxon, why haven't investors caught on?

Unrestricted funding for companies engaged in fossil fuel expansion threatens workers' right to dignified retirement safety, a right that unions have fought hard to win.

ExxonMobil sparked headlines and investor outrage this spring when the company sued its own shareholders over a climate-related shareholder resolution. Public pensions representing trillions in worker savings across the country pushed back and mounted a vote-no effort against CEO Darren Woods and Director Joseph Hooley, but Wall Street asset managers watered down their efforts instead offering unwavering support of Exxon.

To add insult to injury, Woods made an appearance at the Council of Institutional Investors—a nonprofit dedicated to advocating for the investor rights of public, union, and private employee benefit funds—in September. There, he promised to continue to crack down on "extreme" investors who are concerned that the company's business model has loaded the economy with systemic financial risks and instability. Never mind that such a definition of extreme would describe many of the institutions present, which represent over 15 million workers and $5 trillion in assets under management.

But perhaps most indicative of ExxonMobil's commitment to business-as-usual pollution is the bonds they've issued this fall, with a maturity date of 2074.

These long-dated bonds represent unrestricted funds for ExxonMobil to continue to pursue fossil fuel expansion and plastic pollution well past most of the world's—and investors'—Net Zero by 2050 goals. This is an especially risky gamble for investors with long-term obligations, including public pension funds that manage millions of workers' retirement savings.

Not only is the future of oil and gas uncertain, but prolonged pollution wrought by disinformation and investor cash increases economy-wide systemic risks. Investors—and the everyday people who rely on institutions to manage their savings—will be left holding the purse strings as climate change wreaks havoc. Moreover, bond ownership does not come with the shareholder rights investors hope to use to influence company behavior. This gives Exxon complete freedom to use the funds however it wishes, even if that's out of alignment with investor interests.

This increasing risk is why we joined California Common Good and pension beneficiaries to testify during a recent CalPERS Board meeting to ask CalPERS to issue a moratorium on purchasing Exxon bonds.

The Sierra Club represents millions of members, many of whom are saving for retirement in the face of an uncertain future and working tirelessly to protect the communities and places they love. Whether relying on a public pension plan or a private asset manager, our members rely on investment professionals to keep their futures in mind. Unrestricted funding for companies engaged in fossil fuel expansion threatens workers' right to dignified retirement safety, a right that unions have fought hard to win. That's why we call on investors, particularly public pension funds, to refuse to participate in Exxon's bond issuances.

The lies uttered and underwritten by the Koch brothers and ExxonMobil executives—as well as their employees and PACs’ contributions to climate science deniers in Congress—have had serious consequences.

I have spent the better part of the last 12 years writing about lies. My colleagues call it “disinformation,” and I generally do, too, but let’s call it for what it is: lying. During this stretch, I have written more than 200 articles and columns, and most of them were either about CEOs who lie, experts who lie, scientists who lie, attorneys general who lie, legislators who lie, or a president who lies. And I’m not talking about run-of-the-mill white lies. I’m talking about lies that have grave consequences for the future of the planet.

(I should add that I also wrote 65 columns featuring Q&As with scientists and experts who work for my organization, the Union of Concerned Scientists, or UCS. They don’t lie. They follow thescience. The series is called “Ask a Scientist,” and the last one I wrote will run in mid-May.)

After a dozen years unmasking lies and five years before that overseeing UCS’s media relations operation, I am leaving the organization. But before I walk out the door, I wanted to provide a retrospective of some of my columns on the biggest sponsors of climate disinformation in the country: ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods; his predecessor, Rex Tillerson; and Charles Koch, CEO of the coal, oil, and gas conglomerate Koch Industries.

ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson appears at his confirmation hearing on Capitol Hill. (Photo: NBC News/Screengrab)

I wrote more columns about ExxonMobil and its top executives than any other major source of climate lies. Most of these pieces were about the company’s support for a seemingly independent network of anti-regulation, “free-market” nonprofits that spread falsehoods about the reality and seriousness of climate change. ExxonMobil spent at least $39 million on some 70 of these organizations from 1998 through 2020, more than any funder besides Charles Koch and his brother David, co-owner of Koch Industries until his death in 2019.

I first wrote about ExxonMobil in March 2013 after I saw the company’s then-CEO, Rex Tillerson, on the Charlie Rose talk show, who provided me with fodder for perhaps my favorite of two dozen ExxonMobil-related columns.

Rose asked Tillerson open-ended questions on a range of subjects, including climate change and national energy policy. And Rose did, at times, ask follow-up questions. But in nearly every instance, Rose listened politely, refrained from challenging Tillerson on the facts, and went on to his next question. So I decided to write a column in which I pretended to have been on the show alongside Tillerson, calling it “Rex & Me: The Charlie Rose Show You Should Have Seen Last Friday,” a nod to Michael Moore’s first film, Roger & Me.

ExxonMobil wants to be seen as a good corporate citizen. It wants to protect what academics call its “social license,” meaning that it wants to be seen as being legitimate, credible, and trustworthy. At the same time, however, the company has continued to expand oil and gas development and fund climate science denier groups that undermine efforts to address climate change.

The column featured excerpts from Rose and Tillerson’s hour-long conversation with comments I inserted as if I were sitting there in the studio rebutting Tillerson’s statements.

Rose first asked Tillerson about his take on global warming. Repeating his company’s long-standing talking point, Tillerson emphasized scientific uncertainty, despite the fact that Exxon’s own scientists had been warning management about “potentially catastrophic” human-caused global warming since at least 1977. “We have continued to study this issue for decades…,” he said. “The facts remain there are uncertainties around the climate, climate change, why it’s changing, what the principal drivers of climate change are.”

In my retelling of the show, I quickly pointed out that the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had by then concluded that “most” of the increase in average global temperatures since 1950 was “very likely” due to the increase in human-made carbon emissions.

When Rose asked Tillerson if there is a link between extreme weather events and global warming, Tillerson told Rose that he had “seen no scientific studies to confirm [one].” In the original broadcast, Rose went on to another topic. But before he was able to do that in my imaginary scenario, I corrected the record. “There is, in fact, substantial scientific evidence that there’s a strong link between global warming and heat waves and coastal flooding from sea-level rise,” I said. “There’s also a strong link to heavy precipitation and drought, depending on the region and time of the year.”

Later in the hour, Tillerson told Rose that the federal government should end subsidies for renewable energy. “I mean, wind has received subsidies for more than 20 years now,” he said. “Maybe if we took the subsidy off and it was challenged and had to perform, people would take it to a new level.”

It was a bogus argument that fossil fuel proponents would repeat ad nauseum over the next 10 years, so when Rose failed to provide some needed context, I jumped in.

“Rex,” I interjected, “it’s bizarre that your top national energy priority is ending federal support for renewables… [W]hat about the oil and gas industry’s subsidies and tax breaks?” I then explained that, at the time, the oil and gas industry had been receiving an average of $4.86 billion (in 2010 dollars) in federal tax breaks and subsidies for nearly 100 years. “Renewables,” I added, “have gotten peanuts in comparison.”

Four years later, when Tillerson testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee after former President Donald Trump nominated him to be his secretary of state, a senator asked him if he would pursue the Group of 20 pledge to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies. His reply? “I’m not aware of anything the fossil fuel industry gets that I would characterize as a subsidy.”

Exxon CEO Darren Woods speaks at an international energy conference. (Photo: Mark Felix/AFP via Getty Images)

Tillerson’s successor, Darren Woods, now 59, has carried on his company’s tradition of deceit. During an October 2021 hearing the House Oversight and Reform Committee held on the oil industry’s decades-long climate disinformation campaign, Woods—one of four oil company executives testifying that day—was asked if he would “commit right here to stop funding organizations that reject the science of climate change.”

“We do not support climate denial,” he replied. “We do not ask people to lobby for anything different than our publicly supported [climate] positions.”

The history of that lie bears retelling. For years, ExxonMobil executives have acknowledged climate change is happening—but not its cause—and insisted they want to be “part of the solution.” And since 2015, they have claimed that their company supports the goals of the Paris climate agreement, which was brokered that year. Why? ExxonMobil wants to be seen as a good corporate citizen. It wants to protect what academics call its “social license,” meaning that it wants to be seen as being legitimate, credible, and trustworthy. At the same time, however, the company has continued to expand oil and gas development and fund climate science denier groups that undermine efforts to address climate change.

The genesis of ExxonMobil’s brazen hypocrisy can be traced back to 2007. In January of that year, UCS released consultant (now UCS editorial director) Seth Shulman’s report, “Smoke, Mirrors, and Hot Air: How ExxonMobil Uses Big Tobacco’s Tactics to Manufacture Uncertainty on Climate Science,” revealing that the company had spent $16 million between 1998 and 2005 on more than 40 anti-regulation think tanks to launder its message. When asked by a Greenwire reporter a month later about the grantees identified in the UCS report, Kenneth Cohen, then ExxonMobil’s vice president of public affairs, said the company had stopped funding them. Hardly. In 2007 alone, the company gave $2 million to 37 denier groups, including the American Legislative Exchange Council, Heartland Institute, and Manhattan Institute.

In July 2015, after UCS discovered that Exxon (before it merged with Mobil) was aware of the threat posed by climate change more than 30 years earlier and had been intentionally deceiving the public for decades, reporters contacted ExxonMobil spokesman Richard Keil for comment. One reporter asked him about ExxonMobil’s long history of funding climate change denier groups. “I’m here to talk to you about the present,” Keil said. “…We do not fund or support those who deny the reality of climate change.”

I wrote a column a week later dissecting Keil’s carefully crafted whopper. “Technically [Keil was correct], perhaps, because practically no one can say with a straight face that global warming isn’t happening anymore,” I wrote. “Most, if not all, of the people who used to deny the reality of climate change have morphed into climate science deniers. They now concede that climate change is real, but reject the scientific consensus that human activity—mainly burning fossil fuels—is driving it. Likewise, they understate the potential consequences, contend that we can easily adapt to them, and fight government efforts to curb carbon emissions and promote renewable energy. ExxonMobil is still funding those folks, big time.”

By its own accounting, ExxonMobil has continued to fund those folks—albeit fewer of them—to this day. For at least a decade, the company has been listing its grantees in its annual World Giving Report, and beginning in 2015 I wrote a column every year citing how much it gave climate science denier groups the previous year until its 2021 report on its 2020 outlays, when it stopped listing grantees receiving less than $100,000. Previously, its reports included grants of $5,000 or more. That lack of transparency has made it impossible to discern exactly how much the company is still spending on climate disinformation, but nonetheless it amounts to hundreds of thousands of dollars a year.

My 2021 column on the company’s grants from 2020, “Despite Cutbacks, ExxonMobil Continues to Fund Climate Science Denial,” ran two days before Woods and top executives from BP America, Chevron, and Shell testified before the House Oversight Committee. Despite Woods’s insistence at the hearing that his company does not support “climate denial” and does not ask its grantees to support anything other than its official climate-related pronouncements, three ExxonMobil grantees that received at least $100,000 in 2020 contradicted the company’s professed positions. They included a climate science-denying economist at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), which has received more than $5 million from ExxonMobil since 1998; George Washington University’s anti-regulation Regulatory Studies Center, which opposed stronger efficiency standards for home appliances and vehicles that would significantly reduce carbon emissions; and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which at the time dubiously called for “the increased use of natural gas” to “further progress” in addressing climate change.

Since I wrote that column, my last one on ExxonMobil’s annual grants, the company’s Worldwide Giving Report in 2022 indicated that in 2021, ExxonMobil contributed another $150,000 to AEI and $150,000 to the GWU Regulatory Studies Center. The company has yet to publish a report for its grantmaking in 2022, let alone 2023.

Billionaire Charles Koch stands for a portrait on Monday, August 3, 2015 in Dana Point, California. (Photo: Patrick T. Fallon for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

My other bête noire is the 88-year-old libertarian industrialist Charles Koch—the 22th-richest person in the world with a net worth of $67.6 billion—and his network of uber-rich friends and “free-market” think tanks and advocacy groups. From 1997 through 2020, Koch family-controlled foundations donated more than $160 million to at least 90 groups to manufacture doubt about climate science and delay efforts to address global warming—four times more than even what ExxonMobil reportedly spent over the same time period.

Koch is a lot more doctrinaire than his current counterpart at ExxonMobil. Woods downplays the central role human activity—mainly burning fossil fuels—plays in triggering climate change, but he has grudgingly conceded that global warming poses an “existential threat.” Koch, by contrast, has never acknowledged that climate change is a serious problem and has questioned—with no evidence—the veracity of climate models, which studies have found to be quite accurate.

For more than two decades, the Koch network has been diligently spreading disinformation to sabotage efforts to transition to a clean energy economy, more often than not by attacking proposed climate policies on economic grounds. Over the last 12 years, I wrote eight columns on the Koch network’s escapades, including:

But my favorite Koch column is my most recent one, “It’s Time for Charles Koch to Testify About His Climate Change Disinformation Campaign,” which ran in March 2022. I urged the House Oversight Committee to pull Koch in for questioning before it ended its investigation given the fact that he “is as consequential a disinformer as the four oil company executives who testified last fall … combined.”

Unfortunately, the committee did not take my advice, but the column did give me the opportunity to report on the considerable amount Koch Industries’ political action committees (PACs) and employees spend on campaign contributions, how much the company spends on lobbying, and the fact at least 50 Koch network alumni landed key positions in the Trump administration. They included Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, Energy Secretary Rick Perry, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, White House Legislative Affairs Director Marc Short, and… Vice President Mike Pence, who led Trump’s transition team. Egged on by Koch devotees both inside and outside the government—as well as by more than 60 executive branch staff from the Koch-funded Heritage Foundation—the Trump administration rolled back at least 260 regulations, including more than 100 environmental safeguards.

As I said at the beginning of this essay, the lies uttered and underwritten by the Koch brothers and ExxonMobil executives—as well as their employees and PACs’ generous campaign contributions to climate science deniers in Congress—have had serious consequences.

Last year, the United States suffered an unprecedented number of climate change-related billion-dollar disasters, including record heatwaves, drought, wildfires, and floods, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The 28 extreme weather events collectively caused nearly $93 billion in damage. Last year also was hottest in at least 173 years, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service. The annual temperature was 1.48°C (2.66°F) above the preindustrial average.

While the world is burning up, oil industry profits last year—while lower than in 2022—were still quite robust. The two U.S. oil giants, ExxonMobil and Chevron, netted $36 billion and $21.3 billion respectively. Chevron CEO Mike Wirth, one of the oil company executives who testified before the House Oversight Committee in October 2021, boasted that Chevron “returned more cash to shareholders and produced more oil and natural gas [in 2023] than any year in the company’s history.” Meanwhile, Koch Industries’ annual revenue was $115 billion last year, down slightly from $125 billion in 2022. (Because the company is privately held, it is not required to divulge profit data.)

Cities, counties, states, and U.S. territories are now taking steps to hold these and other fossil fuel companies, as well as their trade associations, accountable. So far, some 40 of them have filed 28 lawsuits in state and territory courts for fraud and damages. Chicago and Bucks County, Pennsylvania, 30 miles north of Philadelphia, are the most recent municipalities to file a climate lawsuit. In both cases, the defendants include BP America, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, ExxonMobil, Philips 66, and Shell, as well as the American Petroleum Institute (API), the oil industry’s biggest trade association.

ExxonMobil has been named as a defendant in all of the cases. To date, Koch Industries has been named in only one, filed by the state of Minnesota in June 2020. That lawsuit alleges that API, ExxonMobil, and Koch Industries, which owns an oil refinery in the state, violated state consumer protection laws by misleading Minnesotans about the role fossil fuels play in causing the climate crisis.

As I pointed out in a column about Minnesota’s lawsuit, the state has a storied history when it comes to such litigation. It was one of the first states to sue the tobacco industry, and its lawsuit in the 1990s—the only one that made it to trial—resulted in a groundbreaking settlement of $6 billion over the first 25 years and $200 million annually thereafter. The case also pried 35 million pages of documents from tobacco company files revealing details of the industry’s campaign to sow doubt about the links between smoking and disease. As UCS pointed out in its 2007 exposé of ExxonMobil’s climate disinformation campaign, the tobacco and fossil fuel industries used many of the same strategies and tactics.

U.S. climate litigation is only expected to grow this year, following the U.S. Supreme Court’s rejection of the oil industry’s attempts to transfer climate lawsuits from state courts to federal courts, where industry lawyers believe they are more likely to prevail. If the lawsuits are ultimately successful, courts could order oil companies and their trade associations to pay out hundreds of billions of dollars to impacted communities.

That eventuality, much like the deserved comeuppance the tobacco industry received, would be a just outcome. But even a huge payout wouldn’t begin to compensate for the damage already done by Koch and ExxonMobil lies.