SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

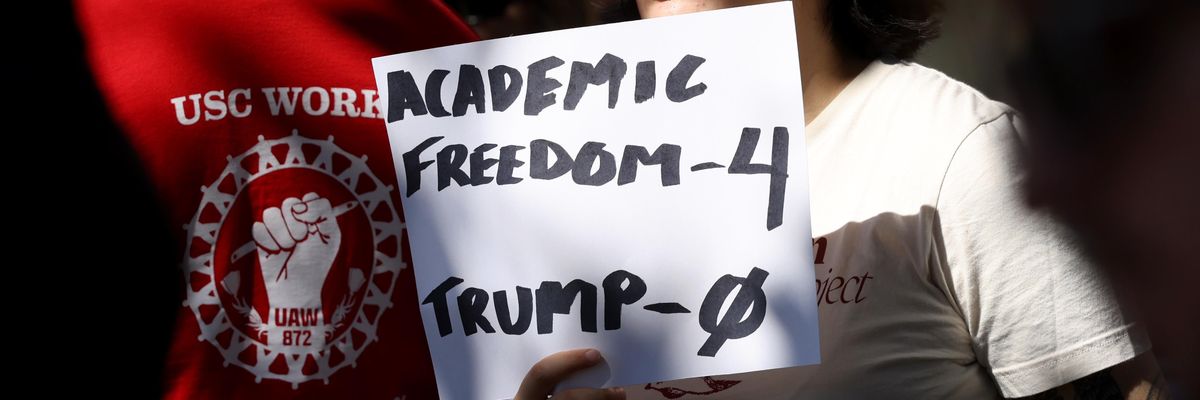

A graduate student joins around a hundred USC academics protesting the Trump education compact that has been offered to the university at USC in Los Angeles on October 17, 2025. USC interim President Beong-Soo Kim rejected the Trump administration's education compact, which would offer priority funding to universities following the president's conservative vision.

Let’s stand together and go on the offensive to create a social democratic vision for higher education and other universal public goods now under assault by Trump and his right-wing allies.

There is no question that the contemporary system of higher education in the United States was facing several crises (commodification of education, access and affordability, faculty precarity, violations of academic freedom, the “rationality crisis”, administrative bloat, etc.—what we generally refer to as the neoliberalization and corporatization of education) before the Trump administration began its assault on colleges and universities in 2025. Trump’s Executive Orders (EOs) related to education have magnified these crises. At the very least, he has forced those of us working in higher education to seriously reflect on what needs fixing. I point to these EOs as an illustration of intent to destroy colleges and universities as public goods by his administration, supporters, and surrogates, including Chris Rufo and Marc Rowan, two of the most notable agents who are not shy about using the authoritarian playbook. They are deliberately pushing the limits of legal and constitutional mores and precedents to achieve their goals. This should not be a controversial interpretation of intent, considering how transparent the expression of the authoritarian turn has been and continues to be when it comes to higher education and, well, everything else.

Their goal, and the goal of at least some elements of the capitalist class, is to dismantle the administrative state as part of the long-running backlash against FDRs New Deal programs that were rooted in the progressive ethos that government should directly serve the needs of the people. The construction of an enemy is crucial in executing the backlash. Today, the targets are, though not exclusively, teachers and what they do in the classroom, college and university professors, immigrants, transgender people, and the working class writ-large. Collectively, it’s time for faculty to show their power, moving beyond the lines of defense they have already established, creating networks of solidarity across industrial sectors, all while conducting political education about how the system works and who benefits under capitalism. It’s time we start to engage in discussing different tactics and overall strategies that include, but are not limited to, building the capacity for strike actions in collaboration with unions nationwide.

The good news, and perhaps to this end, is that Trump’s attacks have galvanized organized opposition from within higher education institutions. A bevy of coalitions led by faculty have taken the lead in pushing back against not only the Trump administration’s Education Department, but also against internal, administrative pressure to comply. The City University of New York (CUNY), the largest urban university system in the United States, led by faculty, has evolved to become one of the leaders in the national call for mutual academic defense compacts across the US. Galvanized by recent attacks on academic freedom and the weaponization of antisemitism by political and administrative actors, the CUNY Alliance to Defend Higher Education is one of the many initiatives that have popped up across the country.

These coalitions have developed under the strain of what feels like daily attacks against the mission of higher education and all its community members, particularly the most vulnerable. This opposition is grounded in the idea that faculty governance should dictate how colleges and universities operate as institutions of higher education focused on the pursuit of truth in the interest of the public good.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education.

At the core of this idea is the material reality that faculty, or faculty labor power, as Clyde W. Barrow has explained, is the sole "producer of value": without faculty, there are no students, no knowledge being produced and taught, therefore no colleges and universities. Historically, administrators—from Board of Trustees, Presidents, Vice Presidents, Provosts, and Deans, what I call the Administrative Elite—are called upon to play a supportive role in the governance of colleges and universities. The employment relation between administrators and faculty is fundamentally a managerial one, where administrative dictates carry the implicit and at times explicit weight of exerting discipline against the perceived violators of college rules, regardless of governance structures and safeguards. To be sure, there are more guardrails against administrative overreach if faculty and staff are protected by a contractual bargaining agreement (CBA) backed by a strong union presence in the workplace. But as we have seen at CUNY and elsewhere, even a CBA cannot stop administrators from acting with McCarthyite impunity.

Colleges and universities, whether public or private, are creatures of the state. Either through regulatory means executed by the state or federal governments or both, through accreditation, or through fiscal dependency, institutions of higher education are subject to the political-economic imperatives of elected politicians and wealthy donors. In turn, they communicate their interests through formal and informal channels directly to boards of trustees, chancelleries, and college and university presidents with the goal of influencing how faculty do our jobs, placing limits on the range of what they deem to be acceptable actions and behavior. To be sure, given the diverse nature of higher education institutions across the country, the Administrative Elite will impose limits to the extent that they are called upon to do so by their respective institutional decision-making hierarchy. While there are well-meaning administrators in positions of power, some who intentionally rise through the ranks of faculty, they are nevertheless subject to the demands placed on them within this hierarchy, oftentimes placing them at odds with competing interests between the state government, politically motivated dictates, and students and faculty, particularly during moments of crisis. We cannot assume that this Administrative Elite will side with faculty and student interests if threats against their institutions are framed as existential. And we cannot convince them to do the “right thing” if their overall material interests are aligned with the dominant political and managerial hierarchy that rules over them.

This brings us to the question of faculty governance. The modern system of faculty self-governance, which dates back to the rise of the modern university in the early 20th century, rests on the assumption that faculty occupy a distinct and “professional” status in American society as intellectuals. The rise of the modern university also coincides with the rise of “corporate liberalism”, within the capitalist state, and the emergence of the corporate university. Historically, the corporate university evolved to adopt the logic and methods of the market as guiding principles which, as Larry G. Gerber has explained, deprofessionalizes and undermines faculty governance.

Since the 1970s, one manifestation of the “market model” that Gerber identifies is the increasing number of precarious employment in the form of “contingent” faculty and the simultaneous decrease in the number of tenure-track faculty lines at colleges and universities. Contingency in employment is one step towards deprofessionalization. The advantages of having a deprofessionalized workforce, as far as managers are concerned, is that workers become vulnerable and more easily subject to employer disciplinary actions. In this case, it also leads to weak faculty governance structures because faculty are already bursting under the full weight of teaching loads, pressure to research and publish, and serve in various committees, leaving no time to participate extensively in governance structures. Some faculty may continue to adjust to the constant juggling of work demands placed on them, while others tune out, keep their heads down, and carry on.

From a broader, social, political, and economic perspective, some faculty may carry on their work under the belief that they are professionals, distinct and separate from other workers who contribute their labor to maintain our workplaces in order. Here, for example, I am thinking of janitorial staff, clerical workers, and safety and security staff. One of the most successful accomplishments of the neoliberalization of the university system is getting us to believe that we are all individuals, working for our own benefit, separate and apart from other workers in a system that commodifies our experience. In other words, the logic of the market obliterates the social relations necessary to produce knowledge. It also produces the belief that as professionals, faculty, in whatever rank, are part of the Professional Managerial Class (PMC), defined by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977 as “salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.”

Christopher Newfield recently captured the consequences of this neoliberalization process. Referring to the current political climate, he says:

Academics are not well prepared for this moment. This was unfortunately foretold by the Ehrenreich prophecy: the PMC was too subservient to capital and its representatives to build an independent power base, in the teeth of disapproval. Not a class but a contradictory class position, academics have a diverse membership that lacked a class interest in aligning with the noncollege working class, in spite of such an interest held by many individual members. They also failed to build organizational power for themselves; instead, they bonded with senior managers and their superiors through academic senates and status-based private bargains, in a stable PMC-capital overlap of interests.

Newfield suggest that,

[W]e must work step by step, in an organizational way, toward direct control of universities. If we do, we’ll be of real use to our knowledge allies—government scientists,public health advocates, local news journalists, community researchers, theater company directors, et al.—in building the self-governing knowledge systems we need to block authoritarian implosion and get a future we want.

As uncomfortable as it may make some individuals who identify and occupy the class position of the PMC, one conclusion that I suggest we draw from Newfield’s observation and analysis is that we must engage in anticapitalist politics within the university and, by extension, at the state level. There’s a reason why Trump deemed this word to be a threat to national security, conflating it with the word anti-fascist.

As the Trump administration continues to exert pressure using the full weight of the federal government, the Justice Department, and compliant Administrative Elites, we must move forward with a clear agenda for improving the system of higher education we have inherited. And I would argue that we must do so in collaboration with labor across different sectors and with the full acknowledgement that education in general and higher education in particular are public goods worth preserving and expanding. We must create the conditions so that the cost of attacking our communities is so high that they’ll at least think twice before doing so. It’s time for New York City labor unions, for example, to exercise their power and work strategically to overcome the legal and ideological limitations that have held them back for decades. For nearly 60 years, as New York State employees, we are prohibited from striking. It’s time we challenge the Taylor Law, which has been hindering our ability to mobilize New York’s working class, and reflect on any lessons to be learned from the 2005 TWU strike.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education. At CUNY, that positive vision should include the democratization of the governance structures and decision-making processes, allowing for community, faculty, and student representation and voting power within the Board of Trustees (BoT). As the institution’s policy-making body, CUNY’s BoT is made up of 17 members, with the vast majority being political appointees (ten appointed by the Governor and five by the Mayor), and only two representing the direct interests of faculty and students (the Chairperson of the University Faculty Senate and the Chairperson of the University Student Senate). Maybe it is time to reflect on and rethink what faculty governance means, in practice, under the existing neoliberal regime where administrators have so much power over university governance.

As part of a democratic and representative discussion, a key question to be addressed is what would a decommodified version of education look like? How can we decouple a college credential from the process of teaching and learning that can inspire students to view a diploma as more than a ticket into the labor market? A crucial component of this positive vision would also include providing full, government-funded free tuition for students and the infrastructure necessary to support their education. The Professional Staff Congress (PSC), the union representing faculty and staff at CUNY, has already taken steps towards achieving this vision.

In the short term, we are bracing ourselves for the Trump show of force to come down on the city, as he has promised, if Zoran Mamdani is elected as our new Mayor in New York City. We need a strong coalition of groups to not only resist but to put forward a positive vision of the city we want. One of these coalitions is already taking shape aiming to “protect and prepare” for the onslaught that is sure to come.

Statements and resolutions are important, at the very least, to set the record straight about which side we are on and where we stand in a time of crisis. But they cannot replace organized, strategic actions that will have a positive impact on our workplaces and our communities. Moments of struggle can bring out the best, and worst, in people. We saw that during the Covid-19 pandemic. Let us not wait but be proactive in this fight. Let’s stand together and go on the offensive to create a social democratic vision for higher education that affirms the value of knowledge and truth-seeking for the benefit of the public good.Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There is no question that the contemporary system of higher education in the United States was facing several crises (commodification of education, access and affordability, faculty precarity, violations of academic freedom, the “rationality crisis”, administrative bloat, etc.—what we generally refer to as the neoliberalization and corporatization of education) before the Trump administration began its assault on colleges and universities in 2025. Trump’s Executive Orders (EOs) related to education have magnified these crises. At the very least, he has forced those of us working in higher education to seriously reflect on what needs fixing. I point to these EOs as an illustration of intent to destroy colleges and universities as public goods by his administration, supporters, and surrogates, including Chris Rufo and Marc Rowan, two of the most notable agents who are not shy about using the authoritarian playbook. They are deliberately pushing the limits of legal and constitutional mores and precedents to achieve their goals. This should not be a controversial interpretation of intent, considering how transparent the expression of the authoritarian turn has been and continues to be when it comes to higher education and, well, everything else.

Their goal, and the goal of at least some elements of the capitalist class, is to dismantle the administrative state as part of the long-running backlash against FDRs New Deal programs that were rooted in the progressive ethos that government should directly serve the needs of the people. The construction of an enemy is crucial in executing the backlash. Today, the targets are, though not exclusively, teachers and what they do in the classroom, college and university professors, immigrants, transgender people, and the working class writ-large. Collectively, it’s time for faculty to show their power, moving beyond the lines of defense they have already established, creating networks of solidarity across industrial sectors, all while conducting political education about how the system works and who benefits under capitalism. It’s time we start to engage in discussing different tactics and overall strategies that include, but are not limited to, building the capacity for strike actions in collaboration with unions nationwide.

The good news, and perhaps to this end, is that Trump’s attacks have galvanized organized opposition from within higher education institutions. A bevy of coalitions led by faculty have taken the lead in pushing back against not only the Trump administration’s Education Department, but also against internal, administrative pressure to comply. The City University of New York (CUNY), the largest urban university system in the United States, led by faculty, has evolved to become one of the leaders in the national call for mutual academic defense compacts across the US. Galvanized by recent attacks on academic freedom and the weaponization of antisemitism by political and administrative actors, the CUNY Alliance to Defend Higher Education is one of the many initiatives that have popped up across the country.

These coalitions have developed under the strain of what feels like daily attacks against the mission of higher education and all its community members, particularly the most vulnerable. This opposition is grounded in the idea that faculty governance should dictate how colleges and universities operate as institutions of higher education focused on the pursuit of truth in the interest of the public good.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education.

At the core of this idea is the material reality that faculty, or faculty labor power, as Clyde W. Barrow has explained, is the sole "producer of value": without faculty, there are no students, no knowledge being produced and taught, therefore no colleges and universities. Historically, administrators—from Board of Trustees, Presidents, Vice Presidents, Provosts, and Deans, what I call the Administrative Elite—are called upon to play a supportive role in the governance of colleges and universities. The employment relation between administrators and faculty is fundamentally a managerial one, where administrative dictates carry the implicit and at times explicit weight of exerting discipline against the perceived violators of college rules, regardless of governance structures and safeguards. To be sure, there are more guardrails against administrative overreach if faculty and staff are protected by a contractual bargaining agreement (CBA) backed by a strong union presence in the workplace. But as we have seen at CUNY and elsewhere, even a CBA cannot stop administrators from acting with McCarthyite impunity.

Colleges and universities, whether public or private, are creatures of the state. Either through regulatory means executed by the state or federal governments or both, through accreditation, or through fiscal dependency, institutions of higher education are subject to the political-economic imperatives of elected politicians and wealthy donors. In turn, they communicate their interests through formal and informal channels directly to boards of trustees, chancelleries, and college and university presidents with the goal of influencing how faculty do our jobs, placing limits on the range of what they deem to be acceptable actions and behavior. To be sure, given the diverse nature of higher education institutions across the country, the Administrative Elite will impose limits to the extent that they are called upon to do so by their respective institutional decision-making hierarchy. While there are well-meaning administrators in positions of power, some who intentionally rise through the ranks of faculty, they are nevertheless subject to the demands placed on them within this hierarchy, oftentimes placing them at odds with competing interests between the state government, politically motivated dictates, and students and faculty, particularly during moments of crisis. We cannot assume that this Administrative Elite will side with faculty and student interests if threats against their institutions are framed as existential. And we cannot convince them to do the “right thing” if their overall material interests are aligned with the dominant political and managerial hierarchy that rules over them.

This brings us to the question of faculty governance. The modern system of faculty self-governance, which dates back to the rise of the modern university in the early 20th century, rests on the assumption that faculty occupy a distinct and “professional” status in American society as intellectuals. The rise of the modern university also coincides with the rise of “corporate liberalism”, within the capitalist state, and the emergence of the corporate university. Historically, the corporate university evolved to adopt the logic and methods of the market as guiding principles which, as Larry G. Gerber has explained, deprofessionalizes and undermines faculty governance.

Since the 1970s, one manifestation of the “market model” that Gerber identifies is the increasing number of precarious employment in the form of “contingent” faculty and the simultaneous decrease in the number of tenure-track faculty lines at colleges and universities. Contingency in employment is one step towards deprofessionalization. The advantages of having a deprofessionalized workforce, as far as managers are concerned, is that workers become vulnerable and more easily subject to employer disciplinary actions. In this case, it also leads to weak faculty governance structures because faculty are already bursting under the full weight of teaching loads, pressure to research and publish, and serve in various committees, leaving no time to participate extensively in governance structures. Some faculty may continue to adjust to the constant juggling of work demands placed on them, while others tune out, keep their heads down, and carry on.

From a broader, social, political, and economic perspective, some faculty may carry on their work under the belief that they are professionals, distinct and separate from other workers who contribute their labor to maintain our workplaces in order. Here, for example, I am thinking of janitorial staff, clerical workers, and safety and security staff. One of the most successful accomplishments of the neoliberalization of the university system is getting us to believe that we are all individuals, working for our own benefit, separate and apart from other workers in a system that commodifies our experience. In other words, the logic of the market obliterates the social relations necessary to produce knowledge. It also produces the belief that as professionals, faculty, in whatever rank, are part of the Professional Managerial Class (PMC), defined by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977 as “salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.”

Christopher Newfield recently captured the consequences of this neoliberalization process. Referring to the current political climate, he says:

Academics are not well prepared for this moment. This was unfortunately foretold by the Ehrenreich prophecy: the PMC was too subservient to capital and its representatives to build an independent power base, in the teeth of disapproval. Not a class but a contradictory class position, academics have a diverse membership that lacked a class interest in aligning with the noncollege working class, in spite of such an interest held by many individual members. They also failed to build organizational power for themselves; instead, they bonded with senior managers and their superiors through academic senates and status-based private bargains, in a stable PMC-capital overlap of interests.

Newfield suggest that,

[W]e must work step by step, in an organizational way, toward direct control of universities. If we do, we’ll be of real use to our knowledge allies—government scientists,public health advocates, local news journalists, community researchers, theater company directors, et al.—in building the self-governing knowledge systems we need to block authoritarian implosion and get a future we want.

As uncomfortable as it may make some individuals who identify and occupy the class position of the PMC, one conclusion that I suggest we draw from Newfield’s observation and analysis is that we must engage in anticapitalist politics within the university and, by extension, at the state level. There’s a reason why Trump deemed this word to be a threat to national security, conflating it with the word anti-fascist.

As the Trump administration continues to exert pressure using the full weight of the federal government, the Justice Department, and compliant Administrative Elites, we must move forward with a clear agenda for improving the system of higher education we have inherited. And I would argue that we must do so in collaboration with labor across different sectors and with the full acknowledgement that education in general and higher education in particular are public goods worth preserving and expanding. We must create the conditions so that the cost of attacking our communities is so high that they’ll at least think twice before doing so. It’s time for New York City labor unions, for example, to exercise their power and work strategically to overcome the legal and ideological limitations that have held them back for decades. For nearly 60 years, as New York State employees, we are prohibited from striking. It’s time we challenge the Taylor Law, which has been hindering our ability to mobilize New York’s working class, and reflect on any lessons to be learned from the 2005 TWU strike.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education. At CUNY, that positive vision should include the democratization of the governance structures and decision-making processes, allowing for community, faculty, and student representation and voting power within the Board of Trustees (BoT). As the institution’s policy-making body, CUNY’s BoT is made up of 17 members, with the vast majority being political appointees (ten appointed by the Governor and five by the Mayor), and only two representing the direct interests of faculty and students (the Chairperson of the University Faculty Senate and the Chairperson of the University Student Senate). Maybe it is time to reflect on and rethink what faculty governance means, in practice, under the existing neoliberal regime where administrators have so much power over university governance.

As part of a democratic and representative discussion, a key question to be addressed is what would a decommodified version of education look like? How can we decouple a college credential from the process of teaching and learning that can inspire students to view a diploma as more than a ticket into the labor market? A crucial component of this positive vision would also include providing full, government-funded free tuition for students and the infrastructure necessary to support their education. The Professional Staff Congress (PSC), the union representing faculty and staff at CUNY, has already taken steps towards achieving this vision.

In the short term, we are bracing ourselves for the Trump show of force to come down on the city, as he has promised, if Zoran Mamdani is elected as our new Mayor in New York City. We need a strong coalition of groups to not only resist but to put forward a positive vision of the city we want. One of these coalitions is already taking shape aiming to “protect and prepare” for the onslaught that is sure to come.

Statements and resolutions are important, at the very least, to set the record straight about which side we are on and where we stand in a time of crisis. But they cannot replace organized, strategic actions that will have a positive impact on our workplaces and our communities. Moments of struggle can bring out the best, and worst, in people. We saw that during the Covid-19 pandemic. Let us not wait but be proactive in this fight. Let’s stand together and go on the offensive to create a social democratic vision for higher education that affirms the value of knowledge and truth-seeking for the benefit of the public good.There is no question that the contemporary system of higher education in the United States was facing several crises (commodification of education, access and affordability, faculty precarity, violations of academic freedom, the “rationality crisis”, administrative bloat, etc.—what we generally refer to as the neoliberalization and corporatization of education) before the Trump administration began its assault on colleges and universities in 2025. Trump’s Executive Orders (EOs) related to education have magnified these crises. At the very least, he has forced those of us working in higher education to seriously reflect on what needs fixing. I point to these EOs as an illustration of intent to destroy colleges and universities as public goods by his administration, supporters, and surrogates, including Chris Rufo and Marc Rowan, two of the most notable agents who are not shy about using the authoritarian playbook. They are deliberately pushing the limits of legal and constitutional mores and precedents to achieve their goals. This should not be a controversial interpretation of intent, considering how transparent the expression of the authoritarian turn has been and continues to be when it comes to higher education and, well, everything else.

Their goal, and the goal of at least some elements of the capitalist class, is to dismantle the administrative state as part of the long-running backlash against FDRs New Deal programs that were rooted in the progressive ethos that government should directly serve the needs of the people. The construction of an enemy is crucial in executing the backlash. Today, the targets are, though not exclusively, teachers and what they do in the classroom, college and university professors, immigrants, transgender people, and the working class writ-large. Collectively, it’s time for faculty to show their power, moving beyond the lines of defense they have already established, creating networks of solidarity across industrial sectors, all while conducting political education about how the system works and who benefits under capitalism. It’s time we start to engage in discussing different tactics and overall strategies that include, but are not limited to, building the capacity for strike actions in collaboration with unions nationwide.

The good news, and perhaps to this end, is that Trump’s attacks have galvanized organized opposition from within higher education institutions. A bevy of coalitions led by faculty have taken the lead in pushing back against not only the Trump administration’s Education Department, but also against internal, administrative pressure to comply. The City University of New York (CUNY), the largest urban university system in the United States, led by faculty, has evolved to become one of the leaders in the national call for mutual academic defense compacts across the US. Galvanized by recent attacks on academic freedom and the weaponization of antisemitism by political and administrative actors, the CUNY Alliance to Defend Higher Education is one of the many initiatives that have popped up across the country.

These coalitions have developed under the strain of what feels like daily attacks against the mission of higher education and all its community members, particularly the most vulnerable. This opposition is grounded in the idea that faculty governance should dictate how colleges and universities operate as institutions of higher education focused on the pursuit of truth in the interest of the public good.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education.

At the core of this idea is the material reality that faculty, or faculty labor power, as Clyde W. Barrow has explained, is the sole "producer of value": without faculty, there are no students, no knowledge being produced and taught, therefore no colleges and universities. Historically, administrators—from Board of Trustees, Presidents, Vice Presidents, Provosts, and Deans, what I call the Administrative Elite—are called upon to play a supportive role in the governance of colleges and universities. The employment relation between administrators and faculty is fundamentally a managerial one, where administrative dictates carry the implicit and at times explicit weight of exerting discipline against the perceived violators of college rules, regardless of governance structures and safeguards. To be sure, there are more guardrails against administrative overreach if faculty and staff are protected by a contractual bargaining agreement (CBA) backed by a strong union presence in the workplace. But as we have seen at CUNY and elsewhere, even a CBA cannot stop administrators from acting with McCarthyite impunity.

Colleges and universities, whether public or private, are creatures of the state. Either through regulatory means executed by the state or federal governments or both, through accreditation, or through fiscal dependency, institutions of higher education are subject to the political-economic imperatives of elected politicians and wealthy donors. In turn, they communicate their interests through formal and informal channels directly to boards of trustees, chancelleries, and college and university presidents with the goal of influencing how faculty do our jobs, placing limits on the range of what they deem to be acceptable actions and behavior. To be sure, given the diverse nature of higher education institutions across the country, the Administrative Elite will impose limits to the extent that they are called upon to do so by their respective institutional decision-making hierarchy. While there are well-meaning administrators in positions of power, some who intentionally rise through the ranks of faculty, they are nevertheless subject to the demands placed on them within this hierarchy, oftentimes placing them at odds with competing interests between the state government, politically motivated dictates, and students and faculty, particularly during moments of crisis. We cannot assume that this Administrative Elite will side with faculty and student interests if threats against their institutions are framed as existential. And we cannot convince them to do the “right thing” if their overall material interests are aligned with the dominant political and managerial hierarchy that rules over them.

This brings us to the question of faculty governance. The modern system of faculty self-governance, which dates back to the rise of the modern university in the early 20th century, rests on the assumption that faculty occupy a distinct and “professional” status in American society as intellectuals. The rise of the modern university also coincides with the rise of “corporate liberalism”, within the capitalist state, and the emergence of the corporate university. Historically, the corporate university evolved to adopt the logic and methods of the market as guiding principles which, as Larry G. Gerber has explained, deprofessionalizes and undermines faculty governance.

Since the 1970s, one manifestation of the “market model” that Gerber identifies is the increasing number of precarious employment in the form of “contingent” faculty and the simultaneous decrease in the number of tenure-track faculty lines at colleges and universities. Contingency in employment is one step towards deprofessionalization. The advantages of having a deprofessionalized workforce, as far as managers are concerned, is that workers become vulnerable and more easily subject to employer disciplinary actions. In this case, it also leads to weak faculty governance structures because faculty are already bursting under the full weight of teaching loads, pressure to research and publish, and serve in various committees, leaving no time to participate extensively in governance structures. Some faculty may continue to adjust to the constant juggling of work demands placed on them, while others tune out, keep their heads down, and carry on.

From a broader, social, political, and economic perspective, some faculty may carry on their work under the belief that they are professionals, distinct and separate from other workers who contribute their labor to maintain our workplaces in order. Here, for example, I am thinking of janitorial staff, clerical workers, and safety and security staff. One of the most successful accomplishments of the neoliberalization of the university system is getting us to believe that we are all individuals, working for our own benefit, separate and apart from other workers in a system that commodifies our experience. In other words, the logic of the market obliterates the social relations necessary to produce knowledge. It also produces the belief that as professionals, faculty, in whatever rank, are part of the Professional Managerial Class (PMC), defined by Barbara and John Ehrenreich in 1977 as “salaried mental workers who do not own the means of production and whose major function in the social division of labor may be described broadly as the reproduction of capitalist culture and capitalist class relations.”

Christopher Newfield recently captured the consequences of this neoliberalization process. Referring to the current political climate, he says:

Academics are not well prepared for this moment. This was unfortunately foretold by the Ehrenreich prophecy: the PMC was too subservient to capital and its representatives to build an independent power base, in the teeth of disapproval. Not a class but a contradictory class position, academics have a diverse membership that lacked a class interest in aligning with the noncollege working class, in spite of such an interest held by many individual members. They also failed to build organizational power for themselves; instead, they bonded with senior managers and their superiors through academic senates and status-based private bargains, in a stable PMC-capital overlap of interests.

Newfield suggest that,

[W]e must work step by step, in an organizational way, toward direct control of universities. If we do, we’ll be of real use to our knowledge allies—government scientists,public health advocates, local news journalists, community researchers, theater company directors, et al.—in building the self-governing knowledge systems we need to block authoritarian implosion and get a future we want.

As uncomfortable as it may make some individuals who identify and occupy the class position of the PMC, one conclusion that I suggest we draw from Newfield’s observation and analysis is that we must engage in anticapitalist politics within the university and, by extension, at the state level. There’s a reason why Trump deemed this word to be a threat to national security, conflating it with the word anti-fascist.

As the Trump administration continues to exert pressure using the full weight of the federal government, the Justice Department, and compliant Administrative Elites, we must move forward with a clear agenda for improving the system of higher education we have inherited. And I would argue that we must do so in collaboration with labor across different sectors and with the full acknowledgement that education in general and higher education in particular are public goods worth preserving and expanding. We must create the conditions so that the cost of attacking our communities is so high that they’ll at least think twice before doing so. It’s time for New York City labor unions, for example, to exercise their power and work strategically to overcome the legal and ideological limitations that have held them back for decades. For nearly 60 years, as New York State employees, we are prohibited from striking. It’s time we challenge the Taylor Law, which has been hindering our ability to mobilize New York’s working class, and reflect on any lessons to be learned from the 2005 TWU strike.

Mobilizing the working class means promoting a long-term, positive vision for public higher education. At CUNY, that positive vision should include the democratization of the governance structures and decision-making processes, allowing for community, faculty, and student representation and voting power within the Board of Trustees (BoT). As the institution’s policy-making body, CUNY’s BoT is made up of 17 members, with the vast majority being political appointees (ten appointed by the Governor and five by the Mayor), and only two representing the direct interests of faculty and students (the Chairperson of the University Faculty Senate and the Chairperson of the University Student Senate). Maybe it is time to reflect on and rethink what faculty governance means, in practice, under the existing neoliberal regime where administrators have so much power over university governance.

As part of a democratic and representative discussion, a key question to be addressed is what would a decommodified version of education look like? How can we decouple a college credential from the process of teaching and learning that can inspire students to view a diploma as more than a ticket into the labor market? A crucial component of this positive vision would also include providing full, government-funded free tuition for students and the infrastructure necessary to support their education. The Professional Staff Congress (PSC), the union representing faculty and staff at CUNY, has already taken steps towards achieving this vision.

In the short term, we are bracing ourselves for the Trump show of force to come down on the city, as he has promised, if Zoran Mamdani is elected as our new Mayor in New York City. We need a strong coalition of groups to not only resist but to put forward a positive vision of the city we want. One of these coalitions is already taking shape aiming to “protect and prepare” for the onslaught that is sure to come.

Statements and resolutions are important, at the very least, to set the record straight about which side we are on and where we stand in a time of crisis. But they cannot replace organized, strategic actions that will have a positive impact on our workplaces and our communities. Moments of struggle can bring out the best, and worst, in people. We saw that during the Covid-19 pandemic. Let us not wait but be proactive in this fight. Let’s stand together and go on the offensive to create a social democratic vision for higher education that affirms the value of knowledge and truth-seeking for the benefit of the public good.