SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"Just one authoritarian thing after another."

US President Donald Trump's White House has reportedly created a scorecard that rates American corporations and trade groups based on how fervently they have promoted Trump's agenda, a move that critics described as part of the president's authoritarian approach to governing and dealing with private businesses.

Axios, which first reported on the White House scorecard Friday, explained that the document "rates 553 companies and trade associations on how hard they worked to support and promote President Trump's 'One Big Beautiful Bill,'" which includes massive corporate tax breaks and unprecedented cuts to safety net programs.

"Factors in the rating include social media posts, press releases, video testimonials, ads, attendance at White House events, and other engagement related to 'OB3,' as the megabill is known internally," the outlet reported. "The organizations' support is ranked as strong, moderate, or low. Axios has learned that 'examples of good partners' on the White House list include Uber, DoorDash, United, Delta, AT&T, Cisco, Airlines for America, and the Steel Manufacturers Association."

The spreadsheet is reportedly being circulated to senior White House staffers and is expected to evolve to gauge companies' support for other aspects of the president's agenda. Corporations that decline to praise Trump's policies—or dare to criticize them—could face government retribution.

"Just one authoritarian thing after another," Rachel Barnhart, a Democratic member of the Monroe County, New York Legislature, wrote in response to the Axios story.

News of the internal "loyalty rating" spreadsheet comes days after Trump reached an unprecedented deal with the chip giants Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices that critics likened to a strongman-style "shakedown." The companies agreed to pay the US government 15% of their revenues from exports to China in exchange for obtaining export licenses.

Trump, who has reported substantial holdings in Nvidia, has hosted company CEO Jensen Huang—one of the richest men in the world—at the White House at least twice this year. Huang has effusively praised the president, calling his policies "visionary."

That's just one example of how major CEOs have sought to flatter Trump, who has proven willing to publicly attack executives—and even demand their resignation.

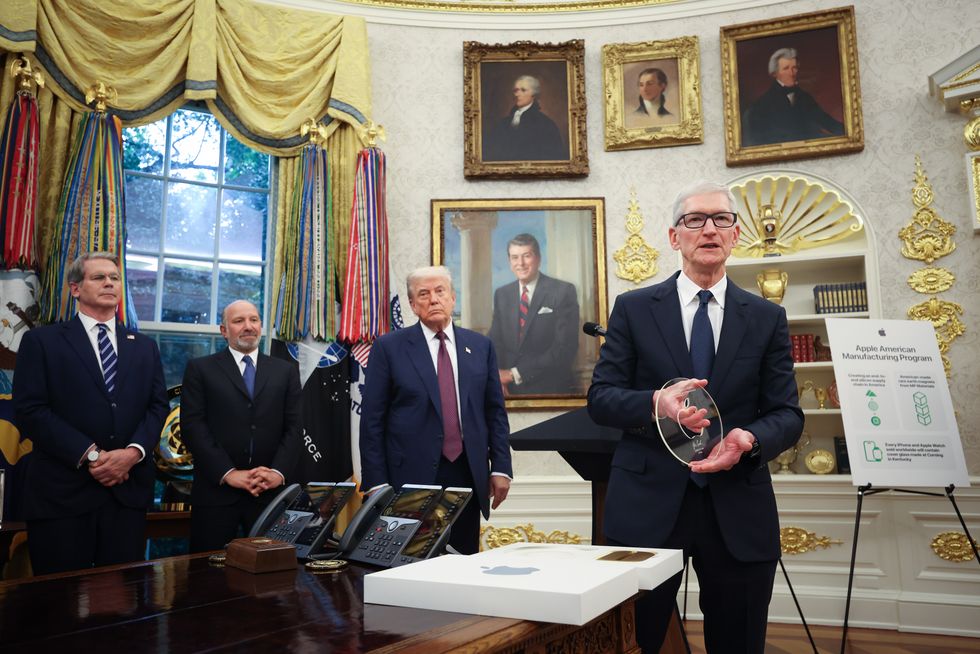

Fortune noted Wednesday that "Apple CEO Tim Cook gave Trump a customized glass plaque mounted on a 24-karat gold stand last week, when he announced his company’s $100 billion investment in domestic production."

Cook also donated $1 million to Trump's inaugural fund.

Companies that have worked to get in the president's good graces appear to be reaping significant rewards.

A Public Citizen analysis published earlier this week found that companies spending big in support of Trump are among the chief beneficiaries of his administration's deregulatory blitz and retreat from corporate crime enforcement.

"Tech corporations facing ongoing federal investigations and enforcement lawsuits that are at risk of being dropped or weakened following the industry's influence efforts include Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Google, Meta, OpenAI, Snap, Uber, Zoom, and Musk-helmed corporations The Boring Company, Neuralink, SpaceX, Tesla, X, and xAI," the group said.

Business journalist Bill Saporito wrote in an op-ed for The New York Times earlier this week that "in ripping up numerous business regulations, Donald Trump seems intent on replacing them with himself."

"The recipient corporations don't necessarily want Mr. Trump's meddling, particularly given his fun house view of economics," Saporito added, "but they can't get away from it."

"The idea that employers would leverage surveillance data to exploit a worker in a desperate position and offer them a lower wage is appalling," said Rep. Rashida Tlaib.

A pair of U.S. House progressives have introduced a bill that would stop companies from using artificial intelligence to set prices and wages based on the personal information of customers and workers.

The "Stop AI Price Gouging and Wage Fixing Act," introduced Wednesday by Reps. Greg Casar (D-Texas) and Rashida Tlaib (D-Mich.), is an effort to curb the growing trend of "surveillance-based price setting," where companies use data from customers to determine how much they are willing to pay for a service.

According to a recent report by the Federal Trade Commission, "Retailers frequently use people's personal information to set targeted, tailored prices for goods and services—from a person's location and demographics, down to their mouse movements on a webpage."

Casar said that "giant corporations should not be allowed to jack up your prices or lower your wages using data they got spying on you."

"Whether you know it or not, you may already be getting ripped off by corporations using your personal data to charge you more," he added. "This problem is only going to get worse, and Congress should act before this becomes a full-blown crisis."

Earlier this month, Delta Airlines announced a pilot program using an AI model to charge individual consumers the maximum amount it determines they are willing to pay for plane tickets. Delta has described the change as "a full reengineering of how we price, and how we will be pricing in the future."

Other companies have been accused of using similar forms of "surge pricing."

Uber, which has been suspected of jacking up prices on riders with low cellphone batteries, pioneered the method. Kroger and Walmart have used digital price tags on goods to rapidly change prices, and Kroger also says it is using facial recognition to track customers in order to offer targeted coupons.

Amazon has been accused of setting personalized prices based on customers' location and browsing history, and the Princeton Review has even been caught charging greater amounts for SAT prep services in Asian communities.

Companies also frequently use hidden algorithms based on personal data to pay workers different wages for the same work—an especially pervasive practice in gig economy jobs like rideshare and delivery driving.

A 2024 report by the Roosevelt Institute found that these algorithms were also being applied to nurses, who were offered shifts by an opaque algorithm based on who was willing to work for the lowest pay and a number of other undisclosed factors.

"It is shameful that companies would use our neighbors' sensitive personal information against them to raise prices," said Tlaib. "The idea that employers would leverage surveillance data to exploit a worker in a desperate position and offer them a lower wage is appalling."

The bill still allows companies to change prices for individuals based on certain circumstances. For example, they would still be allowed to offer discounts to certain groups like college students, veterans, and senior citizens or enact loyalty programs.

Likewise, wage-earners would still be allowed to receive overtime pay or bonuses for good work or have their salaries changed to accommodate the cost of living.

The bill instead targets companies that use underhanded and invasive tactics to take advantage of their customers' and employees' desperation.

"This bill draws a clear line in the sand: Companies can offer discounts and fair wages—but not by spying on people," said the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. "Surveillance-based price gouging and wage setting are exploitative practices that deepen inequality and strip consumers and workers of dignity."

By classifying workers as contractors, platform companies avoid paying core employment obligations while retaining tight control over how the work is done.

Alejandro G. thought that driving full-time for Uber in Houston offered freedom—flexible hours, quick cash, and time to care for his young son. But that promise faded fast.

“There are hours when I make $20,” he told me. “And there are hours when I make $2.” As his pay dropped, he pawned his computer and camera, began rationing the insulin he takes to manage his diabetes—putting his health at risk—and started driving seven days a week, often late into the night, just to break even.

Alejandro, whose real name is withheld for his privacy, is one of millions of workers powering a billion-dollar labor model built on legal loopholes. Companies like Uber insist they are tech platforms, not employers, and that their workers are independent contractors. This sleight of hand allows them to sidestep minimum wage laws, paid sick leave, and other workplace protections, while shifting the financial risks and responsibilities of employment onto the workers. It also lets them avoid employer taxes, draining funds from public coffers.

If gig workers were properly classified, public companies would have to disclose pay data, showing just how far below the median these workers earn, and how high executive compensation soars above them.

A new Human Rights Watch report looks at seven major platform companies operating in the U.S.—Amazon Flex, DoorDash, Favor, Instacart, Lyft, Shipt, and Uber—and finds that their labor model violates international human rights standards. These companies promise flexibility and opportunity, but the reality for many workers is far more precarious. In a survey of 127 platform workers in Texas, we found that after subtracting expenses and benefits, the median hourly pay was just $5.12, including tips. This is nearly 30% below the federal minimum wage, and about 70% below a living wage in Texas.

Seventy-five percent of workers we surveyed said they had struggled to pay for housing in the past year. Thirty-five percent said they couldn’t cover a $400 emergency expense. Over a third had been in a work-related car accident. Many said they sold possessions, relied on food stamps, or borrowed from family and friends to get by. Their labor keeps the system running—but the system isn’t built to work for them.

By classifying workers as contractors, platform companies avoid paying core employment obligations while retaining tight control over how the work is done. The platforms often use algorithms and automated systems to assign jobs, set pay rates, monitor performance, and deactivate workers without warning. In our survey, 65 workers said they feared being cut off from a platform, and 40 had already experienced it. Nearly half were later cleared of wrongdoing.

Companies use incentives that feel like rewards but function more like traps. Uber, Lyft, and DoorDash dangle “quests,” “challenges,” and “surges” to push workers to stay on a shift for longer or hit quotas. These schemes lure workers into chasing bonuses that rarely reflect the true cost of the work. One Uber driver in Houston said, “They are like puppet masters. They psychologically manipulate you.”

Access to higher-paying gigs is also conditioned on behavior. Platforms use customer ratings and performance scores to shape who gets the best jobs. One Shipt worker in Michigan said her pay plummeted immediately after she received two four-star reviews, down from her usual five. Ratings are hard to challenge, and recovering from a low score can take weeks. Workers feel forced to accept every job and appease every customer, reinforcing a system that rewards compliance over fairness.

These aren’t the conditions of self-employment. They’re the conditions of control.

This labor model also drains public resources. In Texas alone, Human Rights Watch estimates that misclassification of platform workers in ride share, food delivery, and in-home services cost the state over $111 million in unemployment insurance contributions between 2020 and 2022. These are public funds that could have strengthened social protection or public services. Instead, they’re absorbed into corporate profits—a quiet transfer of public wealth into private hands.

In 2024, Uber reported $43.9 billion in revenue and nearly $10 billion in net income, calling the fourth quarter its “strongest ever.” DoorDash pulled in $10.72 billion, up 24% from the previous year. Combined, their market valuation exceeds $250 billion.

But workers are pushing back, and policymakers are starting to listen. From June 2 to 13, the 113th session of the International Labour Conference—the United Nations-backed forum where global labor standards are negotiated—will convene to debate a binding treaty on decent work in the platform economy. The message is clear: Workers are demanding rules that protect their rights.

The U.S. can start by updating employment classification standards and adopting clear criteria to determine whether a platform worker is truly independent. We also need greater transparency. If gig workers were properly classified, public companies would have to disclose pay data, showing just how far below the median these workers earn, and how high executive compensation soars above them.

This isn’t about rejecting technology. It’s about making sure new forms of work don’t replicate old forms of exploitation or create new ones, by hiding them behind an app.

Alejandro doesn’t need an algorithm to tell him when to work harder. He has a right to a wage he can live on, protections he can count on, and a system that doesn’t punish him for getting sick, injured, or speaking up.

He and millions like him built the platform economy. It’s time they shared more than the burden.