The Planetary Crime of a Trump Invasion of Greenland

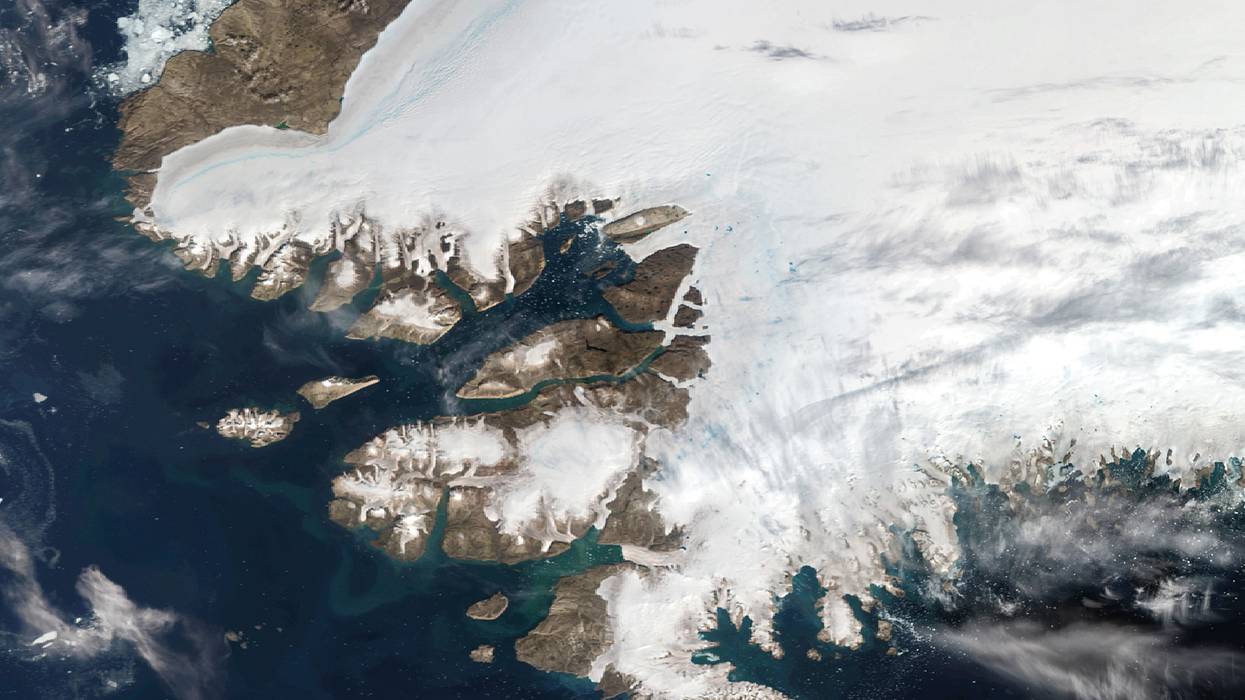

In a rational world, the conversation about the island would be about the melting ice sheet that could easily add a foot or more to the level of the ocean before the century is out.

When President Donald Trump first started fantasizing about seizing Greenland for the US, it sounded farcical—a little Gilbert and Sullivan, or maybe The Mouse that Roared. In the wake of America’s attack on Caracas, however, it now seems as likely as not that we’ll soon be landing troops in Nuuk, a truly hideous prospect that we should all try to head off. Here’s my small effort:

First off, I think it’s a very real possibility.

Here’s Stephen Miller on Monday, talking with Jake Tapper:

TAPPER: Can you rule out the US is going to take Greenland by force?

MILLER: Greenland should be part of the US. By what right does Denmark assert control over Greenland? The US is the power of NATO.

TAPPER: So force is on the table?

MILLER: Nobody is gonna fight the US militarily over future of Greenland.

And here’s our leader himself, speaking to a press gaggle on Air Force One while a beaming Sen. Lindsay Graham (R-Obsequious) grinned by his side:

Trump: We need Greenland. Right now, Greenland is covered with Russian and Chinese ships.

Reporter: What would the justification be for a claim to Greenland?

Trump: The EU needs us to have it.

None of this makes any actual sense—Greenland is not covered with Chinese and Russian ships, the EU does not want us to have it (European leaders united Tuesday to say, “Greenland belongs to its people. It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland,” which seems pretty clear), and Denmark asserts control over Greenland in pretty much the same way Washington asserts control over, say, Alaska or Vermont.

In fact, though, Denmark has been slowly loosening that control over the decades—not because it wants to sell it to America, but because it recognizes that the people who live there, most of whom are Inuit, should have the greatest say in how it’s managed. Greenlanders have exercised that say in ways that would be uncongenial to the White House: for instance, civil partnerships for gay people have been standard since 1996, and gay marriage legal since 2016 when the island’s parliament approved it by a 28-0 vote. Under the Kinguaassiorsinnaajunnaarsagaaneq pillugu inatsit law, sex changes have been allowed since 1976. In other words, Trump’s claim that Greenlanders “want to be with us” is palpable nonsense—a poll last January found that 85% of the population opposed the idea.

Discerning Trump’s “real” reason for wanting Greenland is a pointless exercise; he’s a sad, ancient baby, and babies just want. He seems to think that the point of a ruler is to acquire more territory, and that he more or less owns by divine right the land masses adjacent to our country. (MAGA bloggers this week were busily talking about “vassal states” across the hemisphere). There are minerals there, but hard to get at. Oh, and there’s petroleum in and around Greenland as well, and that usually sings a siren song to this child of the oil-driven 20th century.

Really, however, there’s only one truly vital strategic asset in Greenland, one thing that could change the world. And that’s the ice that covers almost all its landmass.

I’ve been up on this ice sheet—I’ve hiked up glaciers from the tideline, climbing and climbing till the sea disappears behind you and all you can see in every direction is white. It is uncannily beautiful.

I helped organize a trip there in 2018 so that two very fine poets could record a piece from atop this ice sheet. Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner came from her home in the Marshall Islands, which is already slipping under a rising sea (and which has long known about US imperialism; part of the atoll is still radioactive and off limits, thanks to US bomb testing in the 1950s); Aka Niviana is a native Greenlander whose home has begun to melt, a melt that if it continues will guarantee the submersion of Polynesia, and much else.

They stood there on that ice, in a chill summer wind, and recited their long and majestic poem for a camera; my job was to stand just outside its range with a pair of sleeping bags that they could wrap themselves in between takes. “Rise: From One Island to Another,” as their work was called, has won both prizes and large audiences on YouTube; it will, I think, be one of the documents of this global warming era that someday people will look at in a kind of outraged awe, one more proof that we knew exactly what was coming and did nothing about it.

The stakes are so enormous that they make the Trumpian greed for this land seem all the punier and more puerile.

We were camped above the Eagle Glacier—Jason Box, the American-born climatologist now living in Denmark who helped lead the trip had named it that because of its shape when he first visited five years earlier, “but now the head and the wings of the bird have melted away. I don’t know what we should call it now, but the eagle is dead.” And that’s true of so much of the island; we watched as one iceberg after another came crashing off the head of glaciers, each one raising the level of the ocean by some infinitesimal amount.

Greenland holds 23 feet of sea-level rise, should we eventually melt it all. That will take a while, but we’re doing our best. It’s been losing mass steadily for the last quarter-century—it lost 105 billion tons of ice (billion with a b) in 2025, and the ice was melting well into September, unusual in a place where winter usually descends in late August. The people of Greenland, by the way, recognize all this: They passed a law in 2021 banning all new oil exploration and drilling—the government described it as “a natural step” because Greenland “takes the climate crisis seriously.” (More than two-thirds of their power comes from renewables, mostly hydro).

I found those Greenlanders I met to be hardy, thrifty people very much in tune with their place. I spent a memorable afternoon with Box planting trees outside the former American air base in Narsarsuaq in an effort to, among other things, soak up some carbon dioxide. And I spent an equally pleasant afternoon drinking beer with him and the rest of our party at a microbrewery in Saqqannguaq (one of several in the country) which brews “with the purest drinking water on Earth, coming from the Greenlandic ice cap” and hence “free of toxins, chemicals, and microplastics.” Highly recommend the IPA, reminder of yet another imperial adventure.

Obviously seizing Greenland would be a terrible idea because it would break up NATO and put America at loggerheads with the liberal democracies of Europe (though that may be the single biggest incentive for the administration). Obviously, it would be a gross example of modern colonization, obliterating the rights of the people who live there. Obviously, it would raise tensions around the world even higher, and send the strongest possible signal that Beijing should just go grab Taiwan. Lots of people are talking about those things, though there’s not the slightest sign that anyone in power is listening. (Stephen Miller’s wife has tweeted out a map of Greenland decked out in red and white stripes).

But in a rational world what we’d mostly be talking about is all that ice. That’s what, for the other 8 billion people on the planet, actually matters about this island. It could easily add a foot or more to the level of the ocean before the century is out, all by itself (the Antarctic, much bigger but slower to melt, will eventually add much more). A foot is a lot—on a typical beach on, say, the Jersey shore, which slopes up at about 1°, that brings the ocean about 90 feet inland.

And the fresh water pouring off Greenland seems already to be disrupting the great conveyor belt currents that bring warm water north from the equator, maintaining the climates of the surrounding continents. That too could raise—by significant amounts—the level of the sea, especially along the coast of the southeast US (and also plunge Europe into the deep freeze even as the rest of the planet warms).

The stakes are so enormous that they make the Trumpian greed for this land seem all the punier and more puerile. Here’s how Jetnil-Kijiner and Niviana put it in their poem:

We demand that the world see beyond

SUVs, ACs, their pre-package convenience

Their oil-slicked dreams, beyond the belief

That tomorrow will never happen

And yet there’s a generosity to their witness—a recognition that whoever started the trouble, we’re now in it together.

Let me bring my home to yours

Let’s watch as Miami, New York,

Shanghai, Amsterdam, London

Rio de Janeiro and Osaka

Try to breathe underwater…

None of us is immune.

Life in all forms demands

The same respect we all give to money…

So each and every one of us

Has to decide

If we

Will

Rise