Trump’s Gestapo Hits the Streets

The Trump regime follows the Nazi blueprints of violence, threats, and street murders. So it's not hyperbole to say it plainly: they are Nazis.

Trump and many officials in his administration are Nazis. In their policies, their speeches, and their lawless violence, they follow the Nazi playbook of the 1930s. In 1932 the Nazi party gained control of Germany with 37% of the vote. Based on an ideology of Aryan (white) supremacy, they rammed through a series of racist, homophobic and anti-Semitic laws. The Nazis sought to “purify” the nation of non-Aryan blood. Their secret police threatened, beat and murdered suspected opponents. Hitler haughtily ridiculed those targeted by the violence. In all these ways, the Trump administration mimics Nazi plans and programs.

Granted, Nazism relied on one-party authoritarianism, official racism, and the Fuhrer principal. As yet, a two-party system prevails in the US. A further difference between Nazi and MAGA ideology is the ethnic German racism of the former and the white Christian nationalism of the latter. Trump’s strength has been to usurp Christian nationalist resentment about imagined wrongs by immigrants, fear over cultural dilution by foreigners, and certainty that white cultural identity must prevail if the nation is to return to its past greatness. But in creating a cult of personality, ignoring judicial orders, and constituting a lawless federal police, the Nazis have taken possession of the White House ballroom.

Trump’s Gestapo: ICE

Trump’s ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) police resemble the Nazi secret police (Geheime Staatspolizei or Gestapo) in their violence, terror, and even in dress. Hermann Göring’s Gestapo dressed in all-black attire used to strike fear in the masses. The thugs dragged off suspected criminals, surveilled the public, and beat “undesirables” with impunity: Jews, Roma, homosexuals, and political opponents. Hitler believed Gestapo was his "deadliest weapon,” and he gave it unlimited authority to pursue his declared enemies of the regime.

Together with paramilitary “Brownshirts,” the SA (Sturmabteilung), the Gestapo attacked other political parties, disrupting and shutting down assemblies and protests. After the Reichsstag fire of February 1933 that was attributed to Nazi opponents, tens of thousands of Communists, Social Democrats and other political foes were arrested and jailed; many opponents fled the country. A month later, the Reichstag passed the Enabling Act that gave the chancellor of Germany–Hitler–the right to punish anyone he considered an “enemy of the state.” The act allowed “laws passed by the government” to override the constitution.

The real question is why are Republicans silent about the Nazi whose illegal acts and Gestapo-like ICE are destroying the White House?

ICE has become a lawless, federal police force beholden only to Fuhrer Trump. Like the Gestapo, ICE refuses to follow the law, the constitution, and direct court orders. It has established a growing network of jails, some of which are abroad, precisely to avoid judicial oversight. Carrying out the president’s bidding, ICE police swarm the streets to terrorize citizens while claiming to make arrests of deviants and criminals. ICE officers have arbitrarily stopped “Black and Brown Minnesotans” on the street at random, demanding to see their IDs. They enter homes without warrants. ICE is now permitting its lower level police to arrest anyone they encounter – but the basis of arrest is usually skin color and accent. Not surprisingly, more than 70 percent of detained noncitizens have no criminal record. But ICE has a quota to cleanse the streets of 3,000 people daily.

The quotas have led “indiscriminate arrests of immigrants,” and to the expansion of the federal network of concentration camps (¨detention centers”) in Florida, Texas and elsewhere. The camps, boasting inhumane conditions, are Trump’s Dachau, the Nazi’s first concentration camp that opened in 1933. The US government is paying hundreds of millions of dollars in cash for additional warehouses that lack toilets and beds, let alone recreation areas, to store its prisoners. The only surprising thing is that the name “Trump” is not emblazoned on the front of these facilities. Like the Nazi concentration camp guards who separated children from parents, ICE is ripping children from their parents’ arms, deporting minors without parents, kidnapping mothers of the streets, and hunting down children in schools; thirty-two people died in ICE custody in 2025.

If It Dresses Like Gestapo, it is Gestapo

Don Trump says he hires only the best people, but the record of incompetence and high turnover of his government appointees reveals another story: Trump’s upper-level hires are as a rule wealthy, mediocre cronies. Some of their names appear in the Epstein files. To carry out deportations, with the Republican Congress happily earmarking $8 billion for the task, the feds are hiring up to 12,000 ICE agents, reducing their training to six weeks – in fact to 47 days because the Fuhrer is the 47th president, and lowering standards and age requirements so that even 18 year olds can get a $50,000 bonus to join in the mayhem. All of this appeals to immature right-wing young men with infantile fantasies about exercising military power without accountability.

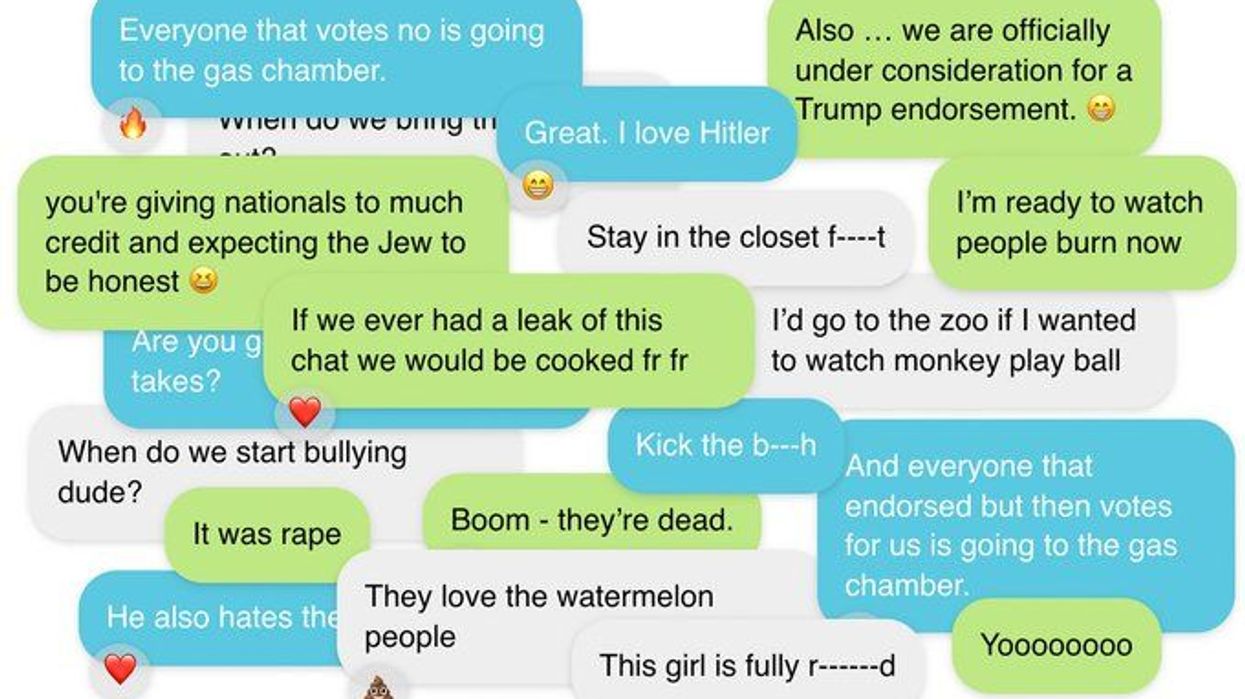

In fact, the recruitment effort for ICE agents relies heavily on right-wing and Nazi slogans and imagery: advertisements talk about taking back and defending the home (land); destroying the flood of foreign invaders; and showing which way the American man leans -- toward law and order, and against invasion and cultural decline. Recruitment targets “male-dominated places and spaces where violence is either required or valorized: gun shows, military bases and local law enforcement,” and elsewhere. The ads depict the work of detaining immigrants as “an epic, heroic quest, with frontier imagery and cowboy-hat clad horsemen.” alongside language like “one homeland, one people, one heritage.”

ICE does not specify a dress code, precisely to make it difficult for people to differentiate between ICE agents, local law enforcement, and even vigilantes who prey on the defenseless. ICE agents usually wear plain clothes or black bulletproof vests. They are fond of grey-hoodies, sunglasses and masks. In the absence of uniforms, ICE impersonators have raped and assaulted women.

Gregory Bovino, until relieved as border control commander last week, left no doubt about his affection for the Gestapo attire. In his Himmler trench coat, as the German media pointed out, Bovino “completed the Nazi look.” Bovino has a long history of reckless violence and racism. He refers to undocumented immigrants as “scum, filth and trash.” He is not shy to utter anti-Semitic comments. In his online presence he augments assault weapons in his photos with inappropriate commentary to justify racial profiling. Bovino’s activities led to a ruling, during the Biden administration, that “masked federal agents brandishing weapons cannot command people going about their daily lives to stop and prove their lawful presence solely because of their skin color, accent, where they happen to be, and the type of work they do.”

But Bovino was quick to violence, and thus a perfect fit for Trump whose Homeland Security chief, Kristi Noem, known for shooting her poorly behaved puppy, abandoned the Biden-era limits. Bovino approved of the shooting of civilian Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, lying to hide ICE culpability. Using similar tactics as the Gestapo, Bovino claims that when his troops use violence, it is the protestors’ fault. He said, “If someone strays into a pepper ball, then that’s on them. Don’t protest and don’t trespass.” He admitted that his storm troopers arrested people based on “how they look.” Bovino’s boss, the Ice-Princess Noem, shares the mantra of racist inequality first and always.

White House Ideology of “Blood and Soil”

Trumpist racist ideology is based on the work of such nineteenth century foundational racists as Arthur de Gobineau. Gobineau argued in 1854 that “Caucasian” civilization was superior to all others. But the more that the white race had contact with lesser races – yellow, red and black – the more impure it became, and civilizations collapsed. The Nazis embraced Gobineau, Howard Stuart Chamberlin, and other such anti-Semites. Trump is clear on this point. He said in 2017: “The fundamental question of our time is whether the West has the will to survive. Do we have the confidence in our values to defend them at any cost? Do we have enough respect for our citizens to protect our borders? Do we have the desire and the courage to preserve our civilization in the face of those who would subvert and destroy it?”

Nazi ideology was anchored into the idea of ethnic purity of the German peasant who was tied to the land through his blood. The slogan “Blut und Boden (Blood and Soil),” meant that (pure) ethnicity and (more) territory were the key to the great German future. The German Volk, a white, Aryan people, had this blood bond to the land, while Jews and others were a danger to it. Hitler believed that the Volk had been deprived of the right to life and land by impure vermin; many Germans in fact believed that those individuals with the "best" genes had been killed in the Great War, while the weak could easily propagate. MAGA ideologues similarly believe that only white people connected with the blood of the founding fathers can protect the legacy of American greatness – or deserve citizenship.

Leading German scientists, racial hygienists, and right wing political figures believed that the state must intervene to protect pure bloodlines and eliminate the weak – through laws, deportation, isolation, sterilization and eventually murder of people considered inferior: foreigners, Jews, Roma, the handicapped, gays and lesbians so that an ideal Nordic race would thrive. Hitler referred to Jews as blood-sucking parasites, rats and subhumans. The odious Trump calls immigrants “vermin” who poison the blood of the nation, and US citizens of Somali descent “garbage.” Congresswoman Ilhan Omar was recently attacked by a crazed MAGA supporter. Trump welcomed the attack, as he urged his followers to “Throw her the hell out!” of the country. The Trumpist effort to clean America of the weak, impure Africans, Muslims, gays and transsexuals thus directly follows that of the Nazis.

Stephen Miller, White House Deputy Chief of Staff, the president’s architect of racist violence, has long spouted the ideas of Gobineau, Chamberlain and other racists of racial inequality; black male stereotypes of criminality; and immigrants as polluters of a pure blood stream. Miller rejects diversity. He joined far-right hate groups in university and organized such campus events as an “Islamo-Fascism Awareness Week.” He prefers the company of white nationalists. He was originally scheduled to serve as the headline speaker at the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017, after which Trump let the world know that there were “very fine people” among the Nazi protestors. Less than 12 hours after using the National Guard to seize control of Washington, DC’s police in August 2025, the White House used its social media page to display photographs of arrested black men – innocent until proven guilty, who had not yet seen a judge, in their mugshots. No doubt, Miller was behind this.

Immigration and Racism: A Tradition of American Right-Wing Violence

The goal of MAGA immigration policies is to make America more white. (Recall that, in January 2024, Trump torpedoed a bipartisan immigration bill to strengthen the southern border, the better to have immigration fears as a tool in the elections and as cudgel to round up Americans in democratic strongholds on the basis of their accents and skin color.) The attacks on Muslims and immigrants in general recall the racist essence of debates over the 1924 Immigration Act which excluded virtually all Asians and Southern Europeans and Jews from entry to the US.

Miller, who is central figure in shaping the Trump Administration’s agenda for promoting state violence against various enemies, prefers a return to the 1920s with its strict quotas to favor white races over “dark” among immigrants. He regrets the famous US “melting pot” of diversity through which “a unified shared national identity was formed.” Miller further laments the passage of civil rights laws of the 1960s which, he claims, attracted more people from “third world” countries who failed to assimilate in the US. This was the “single largest experiment on a society, on a civilization, that had ever been conducted in human history. The result was increased criminality, welfare cheating, and cultural decline. Miller sees the value of “foreign workers” only in their service to white civilization, and in no way worthy of citizenship.

The ongoing campaign of mass deportation to reverse “cultural decline” recalls the 1940 Nazi plan to deport all Jews to Madagascar – before the Nazis embraced the Final Solution to eliminate the Jews in concentration camps. Trump has been a fan of deportation for years. In May 2017, he signed an executive order banning people from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering the country. Tied to the “ban” on Muslims, later overturned in courts, was the threat and reality of child separation to jumpstart “the largest deportation operation in American history” of up to 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States without due process but will full coercive police power of the executive branch. Already, the Trumpists have disappeared people on hundreds of flights, mostly to Central American countries. The Fuhrer is threatening to send US citizens into exile as well.

All of this is fully steeped in white nationalism. The racist-in-chief attacks black majority countries as “shitholes.” He pushes to accept more immigrants from Norway and other white-majority countries, with an exception for white South Africans. He clearly sees the issue not as one of national security, but one of national identity with “whiteness” the only important characteristic of an individual’s worth.

Why Are Republicans Silent?

Trump has been baldly racist since his early days in real estate when he refused to rent his apartments to African-Americans. Lest there be doubt: in 1989, Trump called for the execution of five innocent, but incarcerated black men in a full page advertisement, and he has never retracted that sentiment. The cowardly Trump, who refused to serve in the military, has been quick to call for violence against his nemeses: leaders of countries who refuse to embrace his glory, journalists and protestors at home.

Learning from Nazi tactics, Trump’s politicized Department of Justice (DJ) has accelerated its attack on democrats, majority Democratic states and cities, and the electoral process. The DJ has insisted on the right to examine – and cleanse – state voter rolls. In Georgia in late January 2026, FBI troops raided the Fulton County, Georgia, election office, at Trump’s orders, to seize records, create doubts “ahead of the 2026 midterms,” and overcome the stinging hurt of his 2020 election loss. In fact, the liar-in-chief had tried to convince the Georgia Secretary of State to miscount ballots in 2020. He was assisted in the effort to overturn the fair election by several now convicted felons. And of course, Trump’s ICE regime is directed not at protecting the border, but at attacking cities and states that vote against MAGA: California, Minnesota, Oregon. Any election he loses, Trump claims, is because of cheating election officials and opponents. When he wins, he is silent. If Hitler came to power with just 37% of the vote, why can’t Trump revisit the 2020 election which he lost with just under 47% of the vote?

The Trump regime is corrupt. It follows the Nazi blueprints of violence, threats and street murders. The president fires officials for failing to follow his purge orders. His DOJ is coming after journalists—primarily black and women. It has arrested dozens of them. It carries out early morning raids without warrants. His thugs stop cars, guns drawn, smash windows, drag people to the ground—and shoot protestors. Trump has called for the incarceration of President Obama. Trump owns a copy of Mein Kampf; not surprisingly, in a recent fundraising email, he asked, “Are you a proud American citizen, or does ICE need to come and track you down?” The real question is why are Republicans silent about the Nazi whose illegal acts and Gestapo-like ICE are destroying the White House? Do they fully share his views, or just the ones about poisoning the blood of the nation?