SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

There is a long history of corporations and the state acting in concert to suppress environmental activism. But in recent years the relationship has deepened. This is in part a function of the post-9/11 national security state, which has placed a premium on information sharing between Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, local law enforcement officials and the private sector. In fact, on the same day that TransCanada delivered its presentation to Nebraska law enforcement officials, a representative of the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, a Department of Homeland Security fusion center, also briefed participants on the agency's information-sharing network. According to emails exchanged before the meeting and obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request, "The NIAC will brief on our intelligence sharing role/plan relevant to the pipeline project and provide an overview of a project we are working on."

At the same time, the privatization of intelligence gathering has ballooned with many private security firms now working directly for corporations -- most of which already have their own in-house intelligence gathering and security operations. Annual spending on such services is estimated at $100 billion.

"When those entities merge, and they begin to exchange information, there are extremely serious legal ramifications as well as civil rights consequences to those activities," said Lauren Regan, executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center. "And now I would say we're really seeing gray intelligence [the blurring of public and private intelligence gathering] taken up a notch."

According to Regan, corporations that engage in espionage or intelligence gathering are not bound by the same regulations that state and federal agencies are, in theory, supposed to follow.

"They don't have to abide by the U.S. attorney manual on spying guidelines," Regan said. "They don't even have to go through secretive FISA courts to hack into people's computers or listen in on their cell phone calls."

This is the world in which activists now find themselves. Not only must they contend with the sweeping surveillance powers of the state, brought to light most recently by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, but also the expanding -- and essentially unregulated -- corporate security and intelligence gathering network.

Yet even against this backdrop -- and in the wake of the crackdown on animal rights and environmental groups in the mid-2000s known as the "Green Scare" -- the environmental movement has refashioned itself. Opposition to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and the Keystone XL pipeline have, in just a few years, become highly visible campaigns known for massive protests and acts of civil disobedience.

Such widespread public opposition, no longer limited to a fringe element, has corporations worried. In an email to Lt. Randy Morehead of the Nebraska State Patrol and John McDermott, a crime analyst at the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, TransCanada security director Michael Nagina drew attention to the recently launched Keystone XL Pledge of Resistance, which has gathered nearly 70,000 signatures for acts of peaceful civil disobedience "should it be necessary" to stop the pipeline.

"Certainly not imminent, but a heads up as to the type of action being promoted and the organizations engaged," he wrote. "Note the reference to symbolic targets such as TC [TransCanada] lobbies."

Pieces of the puzzle

In many ways the Keystone XL pipeline is itself a symbolic target. Stopping the pipeline won't bring an end to global warming or to the destructive impacts of the energy industry worldwide. But it will send a message and perhaps lead to a shift in public consciousness; some would argue it already has. Even if the pipeline is approved, which many activists anticipate, the organizational network put in place over the last five years will serve as a foundation for future campaigns.

Ron Seifert, an organizer and spokesperson with Tar Sands Blockade who was featured in TransCanada's PowerPoint presentation, sees the pipeline battle as just one small piece of the puzzle.

"There's a lot of footwork that needs to be done," Seifert said. "The blockade certainly will have the opportunity to continue to do this work long into the future."

In many ways it is a battle over that future -- the future of fossil fuel extraction and energy production -- that TransCanada and other oil and gas companies are waging. In widely circulated remarks at a 2011 natural gas industry conference, a spokesperson for Anadarko Petroleum described the anti-drilling movement as an "insurgency" and encouraged audience members to consult the U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual.

As Anadarko's characterization of the movement suggests, if industry loses the public relations war they will have lost much more than a single pipeline route.

"I see a lot of this coming down to a PR war," said Regan, who also serves as the Tar Sands Resistance legal coordinator. "Right now corporations are afraid that at some point the masses may realize that what they're doing is extremely destructive and we should all get together and oppose the way in which they are profiting off of our health and our environment... They're constantly looking for ways to sway the public to their side versus the noisy millions of activists out there."

One way of swaying the public, or deterring would-be protesters, is to paint the opposition as criminals or terrorists. There are plenty of people who, it appears, are willing to risk arrest to stop a pipeline or protect a watershed. But if those same people are told that by engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience their name might be added to a terror watch list, then they might have second thoughts. By equating above-ground lawful protest with terrorism or criminal activity, corporations are doing everything they can to undermine environmental groups -- from large well-funded outfits like Greenpeace to smaller grassroots organizations like Bold Nebraska.

Yet it is difficult to measure the impact of such tactics -- harassment, intimidation and surveillance -- on social movements. On the one hand, some activists have said that news of TransCanada's collaboration with state and federal law enforcement agencies has only hardened their resolve. On the other hand, we're less likely to hear from those who have been turned away.

"I think that there are networks of people, who are like, 'This is what I want,'" said Scott Parkin, a Senior Campaigner with Rainforest Action Network also featured in the TransCanada presentation. " 'I want to mess with these people so bad that they have files on me.' I think that's one group of people. But there's another level of people who want to get involved and haven't yet. These sorts of things would scare them."

For the time being, however, new activists are continuing to join the fray. At a recent training workshop and protest in Chicago -- the first Keystone Pledge of Resistance action -- nearly all of the participants were newcomers. Or, as Parkin put it, "They were a lot like my mom."

After a one-day training session 22 activists were arrested for blocking the doors of the State Department's Chicago office. The action was a trial run for what Parkin describes as a "training road show" that will canvass 25 cities over the next several weeks. The focus will be on training around 1,000 individuals who have volunteered to lead civil disobedience campaigns against the Keystone XL pipeline.

Meanwhile, Tar Sands Blockade is working with communities in Texas that would be directly impacted by refineries receiving tar sands oil. According to Seifert, they expect to stage demonstrations against TransCanada in August.

"The blockade plans to continue to be active and to continue to work with communities in Texas to do whatever we can, even at the 11th hour, to prevent this pipeline from flowing," Seifert said. "The type of demos and protests the blockade conducts are in a long history of civil disobedience that we are happy to take ownership over and happy to defend in court."

In an email statement TransCanada spokesperson Shawn Howard suggested that such legal recourse was out of the company's hands, saying, "If people decide to break the law then it is up to law enforcement and the courts to determine how people will be held accountable." Howard's comments, however, belie the fact that TransCanada has actively sought communication with Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, the FBI and local law enforcement officials along the pipeline route. They hardly seem willing to leave the matter of prosecuting environmental activists to law enforcement alone.

Above or underground activism

At a recent conference on environmental activism, Lauren Regan, the Civil Liberties Defense Center attorney, spoke about the mechanism of state-corporate repression and its impact on social movements. She said the response from the audience, especially younger activists, was surprising. According to Regan, they were not phased by the growing collaboration between corporations like TransCanada and law enforcement agencies. What they did say was that this kind of pushback had the potential to drive above-ground activism underground.

"I was fairly certain that what these folks were saying is if having demonstrations and holding signs and doing letter writing campaigns and somewhat bland civil disobedience is going to get you on a terrorist bulletin... then I guess the way to do it is to outsmart the corporate spies... and basically poke holes at the corporate machine in a different away," said Regan, who represented Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front members during the Green Scare. She noted a similar kind of logic at play back then. The relatively small number of activists who joined these underground collectives did so because they felt above-ground activism was ineffective but still invited the same kind of repression.

Yet in many ways this played into the hands of the very corporations that activists at the time were ostensibly fighting. Although entirely unfounded, it allowed corporations to brand them as eco-terrorists, and in the public eye they largely succeeded. This also made it much easier for the federal government to launch its own investigation, which included infiltration and surveillance of the radical environmental movement that eventually led to its undoing.

At the same time, the movement itself was deeply divided over the use of arson and property destruction as a tactic. This led to further fragmentation, secrecy and ultimately isolation. But Regan says that many of her clients, some of whom went to prison, no longer advocate such methods. "There has been a change of heart and mind," she said.

So far there is little evidence to suggest that the environmental movement is being driven underground or that activists have lost faith in the power of civil disobedience. If anything the general trend is toward greater participation and openness. This is what the oil and gas industry, through surveillance, harassment and intimidation hopes to curb. The question is: How will activists respond?

Will they play into the hands of the fossil fuel industry and head down the path of secrecy and isolation? Or can they turn the tables and use the tools of repression aimed at undermining peaceful political protest to further the goals of the climate justice movement?

Until recently the energy industry has been able to keep its hardball tactics largely out of public view. But if state, federal and corporate surveillance of environmental activists continues, the noisy millions -- as Regan calls them -- might have even more reason to join the fight. It's an outcome that corporations like TransCanada would like to avoid but one that, paradoxically, they may be helping to set in motion.

This article appears through a collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

There is a long history of corporations and the state acting in concert to suppress environmental activism. But in recent years the relationship has deepened. This is in part a function of the post-9/11 national security state, which has placed a premium on information sharing between Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, local law enforcement officials and the private sector. In fact, on the same day that TransCanada delivered its presentation to Nebraska law enforcement officials, a representative of the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, a Department of Homeland Security fusion center, also briefed participants on the agency's information-sharing network. According to emails exchanged before the meeting and obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request, "The NIAC will brief on our intelligence sharing role/plan relevant to the pipeline project and provide an overview of a project we are working on."

At the same time, the privatization of intelligence gathering has ballooned with many private security firms now working directly for corporations -- most of which already have their own in-house intelligence gathering and security operations. Annual spending on such services is estimated at $100 billion.

"When those entities merge, and they begin to exchange information, there are extremely serious legal ramifications as well as civil rights consequences to those activities," said Lauren Regan, executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center. "And now I would say we're really seeing gray intelligence [the blurring of public and private intelligence gathering] taken up a notch."

According to Regan, corporations that engage in espionage or intelligence gathering are not bound by the same regulations that state and federal agencies are, in theory, supposed to follow.

"They don't have to abide by the U.S. attorney manual on spying guidelines," Regan said. "They don't even have to go through secretive FISA courts to hack into people's computers or listen in on their cell phone calls."

This is the world in which activists now find themselves. Not only must they contend with the sweeping surveillance powers of the state, brought to light most recently by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, but also the expanding -- and essentially unregulated -- corporate security and intelligence gathering network.

Yet even against this backdrop -- and in the wake of the crackdown on animal rights and environmental groups in the mid-2000s known as the "Green Scare" -- the environmental movement has refashioned itself. Opposition to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and the Keystone XL pipeline have, in just a few years, become highly visible campaigns known for massive protests and acts of civil disobedience.

Such widespread public opposition, no longer limited to a fringe element, has corporations worried. In an email to Lt. Randy Morehead of the Nebraska State Patrol and John McDermott, a crime analyst at the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, TransCanada security director Michael Nagina drew attention to the recently launched Keystone XL Pledge of Resistance, which has gathered nearly 70,000 signatures for acts of peaceful civil disobedience "should it be necessary" to stop the pipeline.

"Certainly not imminent, but a heads up as to the type of action being promoted and the organizations engaged," he wrote. "Note the reference to symbolic targets such as TC [TransCanada] lobbies."

Pieces of the puzzle

In many ways the Keystone XL pipeline is itself a symbolic target. Stopping the pipeline won't bring an end to global warming or to the destructive impacts of the energy industry worldwide. But it will send a message and perhaps lead to a shift in public consciousness; some would argue it already has. Even if the pipeline is approved, which many activists anticipate, the organizational network put in place over the last five years will serve as a foundation for future campaigns.

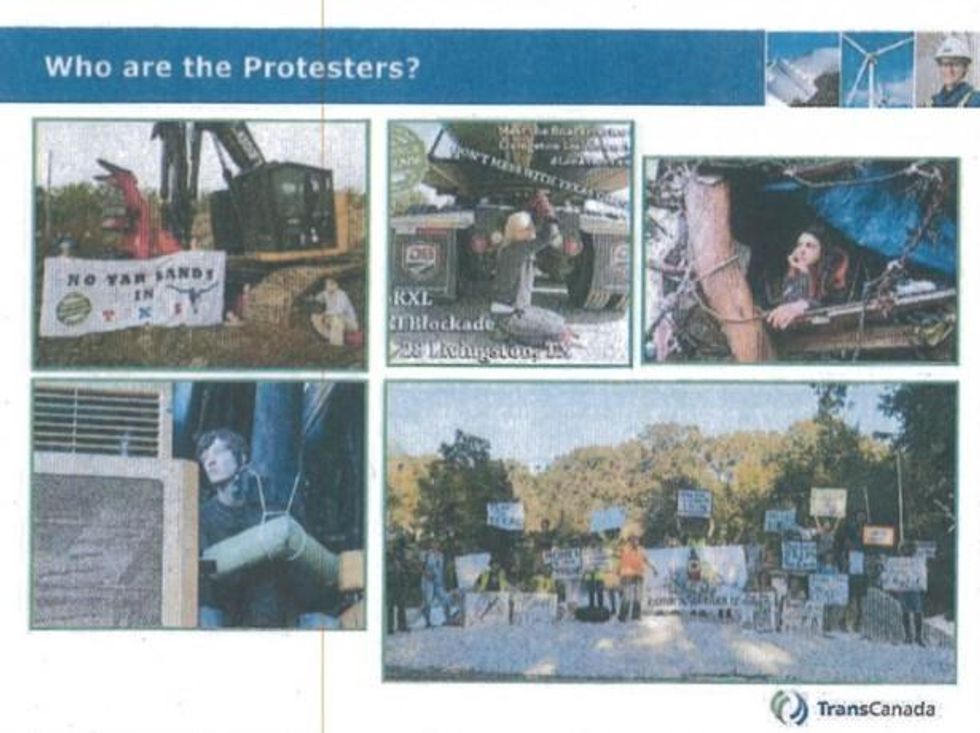

Ron Seifert, an organizer and spokesperson with Tar Sands Blockade who was featured in TransCanada's PowerPoint presentation, sees the pipeline battle as just one small piece of the puzzle.

"There's a lot of footwork that needs to be done," Seifert said. "The blockade certainly will have the opportunity to continue to do this work long into the future."

In many ways it is a battle over that future -- the future of fossil fuel extraction and energy production -- that TransCanada and other oil and gas companies are waging. In widely circulated remarks at a 2011 natural gas industry conference, a spokesperson for Anadarko Petroleum described the anti-drilling movement as an "insurgency" and encouraged audience members to consult the U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual.

As Anadarko's characterization of the movement suggests, if industry loses the public relations war they will have lost much more than a single pipeline route.

"I see a lot of this coming down to a PR war," said Regan, who also serves as the Tar Sands Resistance legal coordinator. "Right now corporations are afraid that at some point the masses may realize that what they're doing is extremely destructive and we should all get together and oppose the way in which they are profiting off of our health and our environment... They're constantly looking for ways to sway the public to their side versus the noisy millions of activists out there."

One way of swaying the public, or deterring would-be protesters, is to paint the opposition as criminals or terrorists. There are plenty of people who, it appears, are willing to risk arrest to stop a pipeline or protect a watershed. But if those same people are told that by engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience their name might be added to a terror watch list, then they might have second thoughts. By equating above-ground lawful protest with terrorism or criminal activity, corporations are doing everything they can to undermine environmental groups -- from large well-funded outfits like Greenpeace to smaller grassroots organizations like Bold Nebraska.

Yet it is difficult to measure the impact of such tactics -- harassment, intimidation and surveillance -- on social movements. On the one hand, some activists have said that news of TransCanada's collaboration with state and federal law enforcement agencies has only hardened their resolve. On the other hand, we're less likely to hear from those who have been turned away.

"I think that there are networks of people, who are like, 'This is what I want,'" said Scott Parkin, a Senior Campaigner with Rainforest Action Network also featured in the TransCanada presentation. " 'I want to mess with these people so bad that they have files on me.' I think that's one group of people. But there's another level of people who want to get involved and haven't yet. These sorts of things would scare them."

For the time being, however, new activists are continuing to join the fray. At a recent training workshop and protest in Chicago -- the first Keystone Pledge of Resistance action -- nearly all of the participants were newcomers. Or, as Parkin put it, "They were a lot like my mom."

After a one-day training session 22 activists were arrested for blocking the doors of the State Department's Chicago office. The action was a trial run for what Parkin describes as a "training road show" that will canvass 25 cities over the next several weeks. The focus will be on training around 1,000 individuals who have volunteered to lead civil disobedience campaigns against the Keystone XL pipeline.

Meanwhile, Tar Sands Blockade is working with communities in Texas that would be directly impacted by refineries receiving tar sands oil. According to Seifert, they expect to stage demonstrations against TransCanada in August.

"The blockade plans to continue to be active and to continue to work with communities in Texas to do whatever we can, even at the 11th hour, to prevent this pipeline from flowing," Seifert said. "The type of demos and protests the blockade conducts are in a long history of civil disobedience that we are happy to take ownership over and happy to defend in court."

In an email statement TransCanada spokesperson Shawn Howard suggested that such legal recourse was out of the company's hands, saying, "If people decide to break the law then it is up to law enforcement and the courts to determine how people will be held accountable." Howard's comments, however, belie the fact that TransCanada has actively sought communication with Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, the FBI and local law enforcement officials along the pipeline route. They hardly seem willing to leave the matter of prosecuting environmental activists to law enforcement alone.

Above or underground activism

At a recent conference on environmental activism, Lauren Regan, the Civil Liberties Defense Center attorney, spoke about the mechanism of state-corporate repression and its impact on social movements. She said the response from the audience, especially younger activists, was surprising. According to Regan, they were not phased by the growing collaboration between corporations like TransCanada and law enforcement agencies. What they did say was that this kind of pushback had the potential to drive above-ground activism underground.

"I was fairly certain that what these folks were saying is if having demonstrations and holding signs and doing letter writing campaigns and somewhat bland civil disobedience is going to get you on a terrorist bulletin... then I guess the way to do it is to outsmart the corporate spies... and basically poke holes at the corporate machine in a different away," said Regan, who represented Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front members during the Green Scare. She noted a similar kind of logic at play back then. The relatively small number of activists who joined these underground collectives did so because they felt above-ground activism was ineffective but still invited the same kind of repression.

Yet in many ways this played into the hands of the very corporations that activists at the time were ostensibly fighting. Although entirely unfounded, it allowed corporations to brand them as eco-terrorists, and in the public eye they largely succeeded. This also made it much easier for the federal government to launch its own investigation, which included infiltration and surveillance of the radical environmental movement that eventually led to its undoing.

At the same time, the movement itself was deeply divided over the use of arson and property destruction as a tactic. This led to further fragmentation, secrecy and ultimately isolation. But Regan says that many of her clients, some of whom went to prison, no longer advocate such methods. "There has been a change of heart and mind," she said.

So far there is little evidence to suggest that the environmental movement is being driven underground or that activists have lost faith in the power of civil disobedience. If anything the general trend is toward greater participation and openness. This is what the oil and gas industry, through surveillance, harassment and intimidation hopes to curb. The question is: How will activists respond?

Will they play into the hands of the fossil fuel industry and head down the path of secrecy and isolation? Or can they turn the tables and use the tools of repression aimed at undermining peaceful political protest to further the goals of the climate justice movement?

Until recently the energy industry has been able to keep its hardball tactics largely out of public view. But if state, federal and corporate surveillance of environmental activists continues, the noisy millions -- as Regan calls them -- might have even more reason to join the fight. It's an outcome that corporations like TransCanada would like to avoid but one that, paradoxically, they may be helping to set in motion.

This article appears through a collaboration with Earth Island Journal.

There is a long history of corporations and the state acting in concert to suppress environmental activism. But in recent years the relationship has deepened. This is in part a function of the post-9/11 national security state, which has placed a premium on information sharing between Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, local law enforcement officials and the private sector. In fact, on the same day that TransCanada delivered its presentation to Nebraska law enforcement officials, a representative of the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, a Department of Homeland Security fusion center, also briefed participants on the agency's information-sharing network. According to emails exchanged before the meeting and obtained through a Freedom of Information Act Request, "The NIAC will brief on our intelligence sharing role/plan relevant to the pipeline project and provide an overview of a project we are working on."

At the same time, the privatization of intelligence gathering has ballooned with many private security firms now working directly for corporations -- most of which already have their own in-house intelligence gathering and security operations. Annual spending on such services is estimated at $100 billion.

"When those entities merge, and they begin to exchange information, there are extremely serious legal ramifications as well as civil rights consequences to those activities," said Lauren Regan, executive director of the Civil Liberties Defense Center. "And now I would say we're really seeing gray intelligence [the blurring of public and private intelligence gathering] taken up a notch."

According to Regan, corporations that engage in espionage or intelligence gathering are not bound by the same regulations that state and federal agencies are, in theory, supposed to follow.

"They don't have to abide by the U.S. attorney manual on spying guidelines," Regan said. "They don't even have to go through secretive FISA courts to hack into people's computers or listen in on their cell phone calls."

This is the world in which activists now find themselves. Not only must they contend with the sweeping surveillance powers of the state, brought to light most recently by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden, but also the expanding -- and essentially unregulated -- corporate security and intelligence gathering network.

Yet even against this backdrop -- and in the wake of the crackdown on animal rights and environmental groups in the mid-2000s known as the "Green Scare" -- the environmental movement has refashioned itself. Opposition to hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, and the Keystone XL pipeline have, in just a few years, become highly visible campaigns known for massive protests and acts of civil disobedience.

Such widespread public opposition, no longer limited to a fringe element, has corporations worried. In an email to Lt. Randy Morehead of the Nebraska State Patrol and John McDermott, a crime analyst at the Nebraska Information Analysis Center, TransCanada security director Michael Nagina drew attention to the recently launched Keystone XL Pledge of Resistance, which has gathered nearly 70,000 signatures for acts of peaceful civil disobedience "should it be necessary" to stop the pipeline.

"Certainly not imminent, but a heads up as to the type of action being promoted and the organizations engaged," he wrote. "Note the reference to symbolic targets such as TC [TransCanada] lobbies."

Pieces of the puzzle

In many ways the Keystone XL pipeline is itself a symbolic target. Stopping the pipeline won't bring an end to global warming or to the destructive impacts of the energy industry worldwide. But it will send a message and perhaps lead to a shift in public consciousness; some would argue it already has. Even if the pipeline is approved, which many activists anticipate, the organizational network put in place over the last five years will serve as a foundation for future campaigns.

Ron Seifert, an organizer and spokesperson with Tar Sands Blockade who was featured in TransCanada's PowerPoint presentation, sees the pipeline battle as just one small piece of the puzzle.

"There's a lot of footwork that needs to be done," Seifert said. "The blockade certainly will have the opportunity to continue to do this work long into the future."

In many ways it is a battle over that future -- the future of fossil fuel extraction and energy production -- that TransCanada and other oil and gas companies are waging. In widely circulated remarks at a 2011 natural gas industry conference, a spokesperson for Anadarko Petroleum described the anti-drilling movement as an "insurgency" and encouraged audience members to consult the U.S. Army/Marine Corps Counterinsurgency Manual.

As Anadarko's characterization of the movement suggests, if industry loses the public relations war they will have lost much more than a single pipeline route.

"I see a lot of this coming down to a PR war," said Regan, who also serves as the Tar Sands Resistance legal coordinator. "Right now corporations are afraid that at some point the masses may realize that what they're doing is extremely destructive and we should all get together and oppose the way in which they are profiting off of our health and our environment... They're constantly looking for ways to sway the public to their side versus the noisy millions of activists out there."

One way of swaying the public, or deterring would-be protesters, is to paint the opposition as criminals or terrorists. There are plenty of people who, it appears, are willing to risk arrest to stop a pipeline or protect a watershed. But if those same people are told that by engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience their name might be added to a terror watch list, then they might have second thoughts. By equating above-ground lawful protest with terrorism or criminal activity, corporations are doing everything they can to undermine environmental groups -- from large well-funded outfits like Greenpeace to smaller grassroots organizations like Bold Nebraska.

Yet it is difficult to measure the impact of such tactics -- harassment, intimidation and surveillance -- on social movements. On the one hand, some activists have said that news of TransCanada's collaboration with state and federal law enforcement agencies has only hardened their resolve. On the other hand, we're less likely to hear from those who have been turned away.

"I think that there are networks of people, who are like, 'This is what I want,'" said Scott Parkin, a Senior Campaigner with Rainforest Action Network also featured in the TransCanada presentation. " 'I want to mess with these people so bad that they have files on me.' I think that's one group of people. But there's another level of people who want to get involved and haven't yet. These sorts of things would scare them."

For the time being, however, new activists are continuing to join the fray. At a recent training workshop and protest in Chicago -- the first Keystone Pledge of Resistance action -- nearly all of the participants were newcomers. Or, as Parkin put it, "They were a lot like my mom."

After a one-day training session 22 activists were arrested for blocking the doors of the State Department's Chicago office. The action was a trial run for what Parkin describes as a "training road show" that will canvass 25 cities over the next several weeks. The focus will be on training around 1,000 individuals who have volunteered to lead civil disobedience campaigns against the Keystone XL pipeline.

Meanwhile, Tar Sands Blockade is working with communities in Texas that would be directly impacted by refineries receiving tar sands oil. According to Seifert, they expect to stage demonstrations against TransCanada in August.

"The blockade plans to continue to be active and to continue to work with communities in Texas to do whatever we can, even at the 11th hour, to prevent this pipeline from flowing," Seifert said. "The type of demos and protests the blockade conducts are in a long history of civil disobedience that we are happy to take ownership over and happy to defend in court."

In an email statement TransCanada spokesperson Shawn Howard suggested that such legal recourse was out of the company's hands, saying, "If people decide to break the law then it is up to law enforcement and the courts to determine how people will be held accountable." Howard's comments, however, belie the fact that TransCanada has actively sought communication with Department of Homeland Security fusion centers, the FBI and local law enforcement officials along the pipeline route. They hardly seem willing to leave the matter of prosecuting environmental activists to law enforcement alone.

Above or underground activism

At a recent conference on environmental activism, Lauren Regan, the Civil Liberties Defense Center attorney, spoke about the mechanism of state-corporate repression and its impact on social movements. She said the response from the audience, especially younger activists, was surprising. According to Regan, they were not phased by the growing collaboration between corporations like TransCanada and law enforcement agencies. What they did say was that this kind of pushback had the potential to drive above-ground activism underground.

"I was fairly certain that what these folks were saying is if having demonstrations and holding signs and doing letter writing campaigns and somewhat bland civil disobedience is going to get you on a terrorist bulletin... then I guess the way to do it is to outsmart the corporate spies... and basically poke holes at the corporate machine in a different away," said Regan, who represented Earth Liberation Front and Animal Liberation Front members during the Green Scare. She noted a similar kind of logic at play back then. The relatively small number of activists who joined these underground collectives did so because they felt above-ground activism was ineffective but still invited the same kind of repression.

Yet in many ways this played into the hands of the very corporations that activists at the time were ostensibly fighting. Although entirely unfounded, it allowed corporations to brand them as eco-terrorists, and in the public eye they largely succeeded. This also made it much easier for the federal government to launch its own investigation, which included infiltration and surveillance of the radical environmental movement that eventually led to its undoing.

At the same time, the movement itself was deeply divided over the use of arson and property destruction as a tactic. This led to further fragmentation, secrecy and ultimately isolation. But Regan says that many of her clients, some of whom went to prison, no longer advocate such methods. "There has been a change of heart and mind," she said.

So far there is little evidence to suggest that the environmental movement is being driven underground or that activists have lost faith in the power of civil disobedience. If anything the general trend is toward greater participation and openness. This is what the oil and gas industry, through surveillance, harassment and intimidation hopes to curb. The question is: How will activists respond?

Will they play into the hands of the fossil fuel industry and head down the path of secrecy and isolation? Or can they turn the tables and use the tools of repression aimed at undermining peaceful political protest to further the goals of the climate justice movement?

Until recently the energy industry has been able to keep its hardball tactics largely out of public view. But if state, federal and corporate surveillance of environmental activists continues, the noisy millions -- as Regan calls them -- might have even more reason to join the fight. It's an outcome that corporations like TransCanada would like to avoid but one that, paradoxically, they may be helping to set in motion.

This article appears through a collaboration with Earth Island Journal.