SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

His new dietary guidelines promoting saturated fats are a recipe for disaster, and a heart attack.

Fat is now phat, at least according to Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

When President Donald Trump’s Health and Human Services (HHS) secretary unveiled new federal dietary guidelines this January, he declared: “We are ending the war on saturated fats.” Seconding Kennedy was Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Marty Makary, who promised that children and schools will no longer need to “tiptoe” around fat.

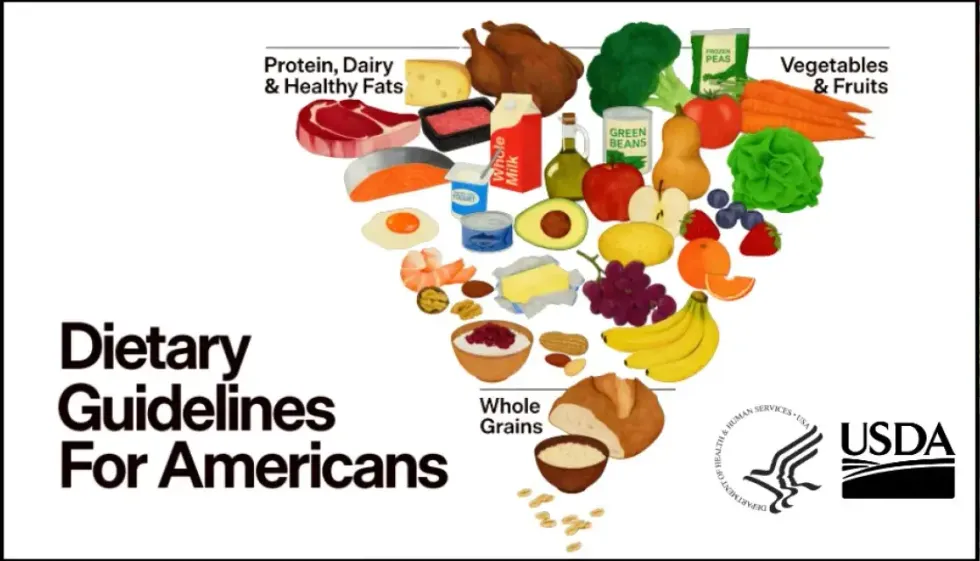

Kennedy’s exaltation of fat comes complete with a new upside-down guidelines pyramid where a thick cut of steak and a wedge of cheese share top billing with fruit and vegetables. This prime placement of a prime cut is the strongest endorsement for consuming red meat since the government first issued dietary guidelines in 1980.

The endorsement reverses decades of advisories, which the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) and HHS jointly issue every five years, to limit red meat consumption issued under both Democratic and Republican administrations given the strong evidence that eating less of it lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease. Multiple studies over the last decade have linked red and processed meats not only to cardiovascular disease, but also to colon polyps, colorectal cancer, diabetes, diverticulosis, pneumonia, and even premature death.

Given the scientific evidence, we should intensify the war against saturated fats, not call it off.

The new dietary guidelines even contradict those issued under the first Trump administration just five years ago, warning Americans not to eat too much saturated fat. “There is little room,” those guidelines stated, “to include additional saturated fat in a healthy dietary pattern.” A significant percentage of saturated fat comes from red meat. Americans, who account for only 4% of the people on the planet, consume 21% of the world’s beef.

Kennedy’s fatmania even extends to beef tallow and butter, which the new pyramid identifies—along with olive oil—as “healthy fats” for cooking. In fact, beef tallow is 50% saturated fat. Butter is nearly 70%. Olive oil, meanwhile, is just 14% saturated fat and is, indeed, healthy.

This rendering of recommended fats muddles a message that could have been stunningly refreshing, given the Trump administration’s penchant for meddling with science. Some of the new pyramid’s recommendations were applauded by mainstream health advocacy groups, particularly one advising Americans to consume no more than 10 grams of added sugar per meal and others, as Kennedy pointed out, calling for people to “prioritize whole, nutrient-dense foods—protein, dairy, vegetables, fruits, healthy fats, and whole grains—and dramatically reduce highly processed foods.”

But such wholesomeness could easily be wasted if Americans increase their meat consumption. That would not, as Kennedy professes, make America healthy again. Given the scientific evidence, we should intensify the war against saturated fats, not call it off.

The 420-page report by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee prepared in 2024 for the USDA and HHS found that more than 80% of Americans consume more than the recommended daily limit of saturated fat, which is about 20 grams—10% of a 2,000 calorie-per-day diet. The report concluded that replacing butter with plant-based oils and spreads higher in unsaturated fat is associated with lower cardiovascular disease risk and eating plant-based foods instead of meat is “associated with favorable cardiovascular outcomes.”

A March 2025 peer-reviewed study in JAMA Internal Medicine came to a similar conclusion. It found that eating more butter was associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. Using plant-based oils instead of butter, the researcher found, was associated with a 17% lower risk of death. Such a reduction in mortality, according to study co-author Dr. Daniel Wang, means “a substantial number of deaths from cancer or from other chronic diseases … could be prevented” by replacing butter with such plant-based oils as soybean or olive oil.

What does a “substantial” number of deaths look like? Heart disease is the No. 1 killer in the United States, and heart disease and stroke kill more people than all cancers and accidents combined. The annual number of American deaths tied to cardiovascular disease is creeping toward the million mark. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), it killed more than 940,000 people in 2022.

Over the next 25 years, AHA projects that the incidence of high blood pressure among adults will increase from 50% today to 61%, obesity rates will jump from 43% to 60% and diabetes will afflict nearly 27% of Americans compared to 16% today. Reducing mortality by 17% for those and other related health problems would go a long way to make Americans healthier.

A good place to begin reducing food-related mortality is by cutting highly processed foods out of the American diet. That would require a drastic change in eating habits for a lot of people. A July 2022 study found that nearly 60% of calories in the average American diet comes from ultra-processed foods, which have been linked to cancer, cardiovascular disease, depression, diabetes, and obesity.

One of the main culprits is fast food. A January 2025 study of the six most popular fast-food chains in the country—Chick-fil-A, Domino’s Pizza, McDonald’s, Starbucks, Subway and Taco Bell—found that 85% of their menu items were ultra-processed. And, according to a 2018 study, more than a third of US adults dine at a fast-food chain on any given day, including nearly half of those aged 20 to 39.

Our overreliance on fast food presents a huge conundrum. US food systems are structured in a way that it is unlikely you can tell people to cut processed foods and eat more meat at the same time. Hamburgers and processed deli meat are among the main ways Americans consume red meat. And given the blizzard of TV ads for junk food and fast-food joints, which have proliferated across the country and especially in low-income food deserts—it is also unlikely that many people will use the new guidelines to comb through their local grocer’s meat department for the leanest (and often most expensive) cut of beef.

According to the University of Connecticut’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Health, food, beverage, and restaurant companies spend $14 billion a year on advertising in the United States. More than 80% of those ad buys are for fast food, sugary drinks, candy, and unhealthy snacks. That $14 billion is also 10 times more than the $1.4 billion fiscal year 2024 budget for chronic disease and health promotion at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And don’t expect the CDC to get into an arms race with junk food advertisers any time soon. Kennedy slashed the CDC staff by more than 25%, from 13,500 to below 10,000.

All of this adds up to the probability that Americans will see the new guidelines’ recommendation to eat red meat as a green light to gorge on even more burgers and other fast-food, ultra-processed meat.

The new guidelines’ green light for consuming red meat and saturated fats is particularly vexing given the guidelines produced five years ago during Trump’s first term did not promote them. Why the about-face?

During the run-up to Trump’s second term, the agribusiness industry went into overdrive to install Trump in the White House and more Republicans in Congress. In 2016, agribusinesses gave Trump $4.6 million for his campaign, nearly double what it gave Hillary Clinton. But in 2024, they gave Trump $24.2 million, five times what it gave Kamala Harris. Agribusinesses also donated $1 million to Kennedy’s failed 2024 campaign, making him the fourth-biggest recipient among all presidential candidates during that election cycle.

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is nowhere near making America healthy again by declaring in his new food pyramid that red meat is as healthy as broccoli, tomatoes, and beans.

Despite claiming he wanted dietary guidelines “free from ideological bias, institutional conflicts, or predetermined conclusions,” Kennedy rejected the recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee and turned over the nation’s dietary data to 9 review authors, at least 6 of whom had financial ties to the beef, dairy, infant-formula, or weight-loss industry.

Three of them have received either research grant funding, honoraria, or consulting fees from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, which is known for funding dubious research downplaying or dismissing independent scientific findings that show read meat to be threat to public health and the environment. In 2024, the trade group gave nearly all of its $1.1 million in campaign contributions to Republican committees and candidates.

Kim Brackett, an Idaho rancher and vice president of the beef industry trade group, hailed the new guidelines, claiming “it is easy to incorporate beef into a balanced, heart-healthy diet.”

Perhaps, but the grim reality is most Americans do not follow a balanced, heart-healthy diet. Four out of five of us are already consuming more than the recommended daily limit of saturated fat and we are well on our way to a 60% obesity rate.

So, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is nowhere near making America healthy again by declaring in his new food pyramid that red meat is as healthy as broccoli, tomatoes, and beans. Beholden to Big Beef, he is driving us full speed ahead on the road to a collective heart attack.

This article first appeared at the Money Trail blog and is reposted here at Common Dreams with permission.

Changing your diet isn’t the only way to help tackle factory farming; instead, you can donate to charities working to make a difference.

As holiday dishes parade across dining tables nationwide, there’s one question we often try to avoid: Where did my food actually come from?

Every holiday season, Americans consume millions of turkeys, hams, and other festive fare. The uncomfortable reality is that about 99% of the meat in the US comes from factory farms: industrial facilities with crowded conditions, which pollute the environment and push traditional farms out of business.

But this isn’t what we want to think about when we’re celebrating. And we certainly don’t want to swap turkey for tofu.

Here’s the good news: Changing your diet isn’t the only way to help tackle factory farming, and it probably isn’t even the best way. Instead, you can keep eating meat and donate to "offset" your impact. Think of carbon offsets, not just for the climate, but for animal welfare as well.

The meat industry would love us to debate individual food choices endlessly rather than examine the system they’ve created.

This is because some of the charities working to change factory farming are so good at what they do that it really doesn’t cost much to make a big difference. In fact, it would cost the average American about $23 a month to do as much good for animals and the planet as going vegan. Even with all the trimmings, Thanksgiving dinner costs you less than a dollar to offset.

Despite campaigns like Meatless Mondays and Veganuary, meat eating is still on the rise globally. About 5% of US adults identify as vegan or vegetarian, and for years that number has remained stagnant. The "diet change strategy" just isn’t moving us in the right direction.

On the other hand, charities have made huge gains in improving the lives of farm animals and pushing for a more sustainable food system. Groups such as The Humane League, or THL, have pressured major food companies to eliminate cruel practices, like confining egg-laying hens in cages too small to spread their wings. Thanks to THL and others, 40% of US hens are now cage-free, up from just 4% when they started.

But is it hypocritical to keep eating meat and pay a bit of money to feel less guilty?

Not necessarily, if the goal is to make a genuine difference.

In fact, emphasis on individual action has often held movements back. In the early 2000s, one of the biggest promoters of the "carbon footprint"—the idea of measuring and reducing your personal impact on global warming—was the oil giant BP. Shifting the focus from the role of big business to consumer choice plays into the hands of the world’s biggest polluters. In the same way, the meat industry would love us to debate individual food choices endlessly rather than examine the system they’ve created.

Instead, we need systemic change: supporting organizations that push for better regulations, fighting harmful agricultural subsidies, and holding companies accountable for their practices.

Most importantly, writing a check is a much easier ask than changing your entire diet, which means more people will actually help. We know people are willing to give their money to animal causes: About 12% of Americans do it, more than twice as many people as are vegetarian or vegan.

Right now, billions of animals are suffering in factory farms while we argue about what’s on our plates. The fastest path to ending their suffering isn’t waiting for everyone to go vegan: It just needs enough of us to put our money where our mouth is.

Rebalancing industrial animal farming cuts emissions, limits disease risk, protects biodiversity, and strengthens food security, reminding us that human, animal, and planetary well-being are inseparable.

Every year, world leaders gather to tackle the climate crisis. They promise to cut emissions, restore forests, and invest in a greener future. Yet one of the most powerful tools for change often goes unmentioned: the food on our plates.

After more than a decade of working in, and with, the United Nations, I’ve learned something crucial: Food sits at the center of everything we are trying to protect—our climate, biodiversity, health, and livelihoods. This year, for the first time, food systems are formally part of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of Parties (UNFCCC COP30) Action Agenda—a long-overdue recognition of their central role in solving the climate crisis. Still, too often, they remain the missing piece in global climate discussions.

The science is clear. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that food systems—from how we grow and process food to how we transport and waste it—account for about a third of global greenhouse gas emissions.

The message is simple: We cannot fix the climate crisis while ignoring what we eat.

This reality should give us hope. Food offers a solution that is immediate, inclusive, and within reach. Every meal is a chance to make things better.

Plant-rich eating is not a trend or a restriction. It is a climate solution, backed by science and rooted in fairness. Research in Nature shows plant-rich diets produce 75% less climate-heating emissions compared with high-meat diets, while using 75% less land and 54% less water. By eating this way, we can cut global food emissions by nearly one-third, improve public health, and ease the pressure on forests and ecosystems.

As negotiations unfold in Belém, COP30 offers a historic opportunity to embed food systems into the heart of climate policy.

But consumption is only part of the picture. World leaders must change how food is produced. Industrial farming, which relies heavily on deforestation and feed crop production, drives much of the problem. At COP30, hosted in Brazil, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has pledged bold action to protect forests, including a $1 billion commitment to the Tropical Forests Forever Fund. Reducing the expansion of soy and maize for feed—a major driver of deforestation—is essential not only for reducing emissions, but also for helping communities adapt, especially in vulnerable regions.

At Compassion in World Farming, we see this every day in our work with farmers, policymakers, and communities. Agroecological and regenerative practices, such as crop rotation, help restore soils and reduce the need for synthetic fertilizers. They also align with traditional and Indigenous knowledge that works with nature rather than against it.

As a father of a Gen Alpha child, I think about what kind of planet my daughter will inherit. We eat three times a day, every day, and we will do it for the rest of our lives. Our choices shape whether her world is sustainable or fragile.

I have been part of countless UN meetings and summits on climate, food systems, and sustainable development. In the past year, I have witnessed growing momentum across the UN system to integrate food into climate discussions, especially following the UN Food Systems Summit (UNFSS) and the COP28 Declaration on Food and Agriculture’s recommendations. This shift is encouraging and signals the world is ready to treat food systems as central to climate action.

When I look at my daughter’s future, I want to believe that we will have the courage to connect these dots: to see that what we grow and eat is not just personal preference but global policy.

At COP30 in Belém, governments have a chance to change course. To do so, they must:

These shifts must fit local realities. In the Global South, diets, cultural traditions, and nutritional needs vary widely. Supporting plant-rich diets must go hand in hand with respecting local contexts and ensuring food sovereignty.

Reframing food as climate action must include the recognition that human, animal, and planetary health are deeply connected and dependent. Rebalancing industrial animal farming cuts emissions, limits disease risk, protects biodiversity, and strengthens food security, reminding us that human, animal, and planetary well-being are inseparable.

As negotiations unfold in Belém, COP30 offers a historic opportunity to embed food systems into the heart of climate policy—not just as a mitigation tool, but as a pathway for adaptation, resilience, and equity. Global action on food must reflect its true potential: to drive down emissions, regenerate ecosystems, and chart a more sustainable future for everyone.

This is the climate leadership we need: bold, inclusive, and rooted in the principle that climate action begins with what we eat.