In April of 2003, I returned from Iraq after having lived there during the U.S. Shock and Awe bombing and the initial weeks of the invasion. Before the bombing I had traveled to Iraq about two dozen times and had helped organize 70 trips to Iraq, aiming to cast light on a brutal sanctions regime, with the "Voices in the Wilderness" campaign. As the bombing had approached, we had given our all to helping organize a remarkable worldwide peace movement effort, one which may have come closer than any before it to stopping a war before it started. But, just as, before the war, we'd failed to lift the vicious and lethally punitive economic sanctions against Iraq, we also failed to stop the war, and the devastating civil war that it created.

So it was April and I'd returned home, devastated at our failure. My mother possessed ample reserves of Irish charm, motherly wisdom, and, for purposes of political analyses, a political analysis consistent with that of Fox News Channel. She knew I was distraught, and aiming to comfort me, she said the following in her soft, lilting voice. "Kathy, dear, what you don't understand is that the people of Iraq could have gotten rid of Saddam Hussein a long time ago, and they ought to have done so, and they didn't. So we went in there and did it for them." She clearly hoped I could share her relief that the U.S. could lend a helping hand in that part of the world. "And they ought to be grateful, and they're not."

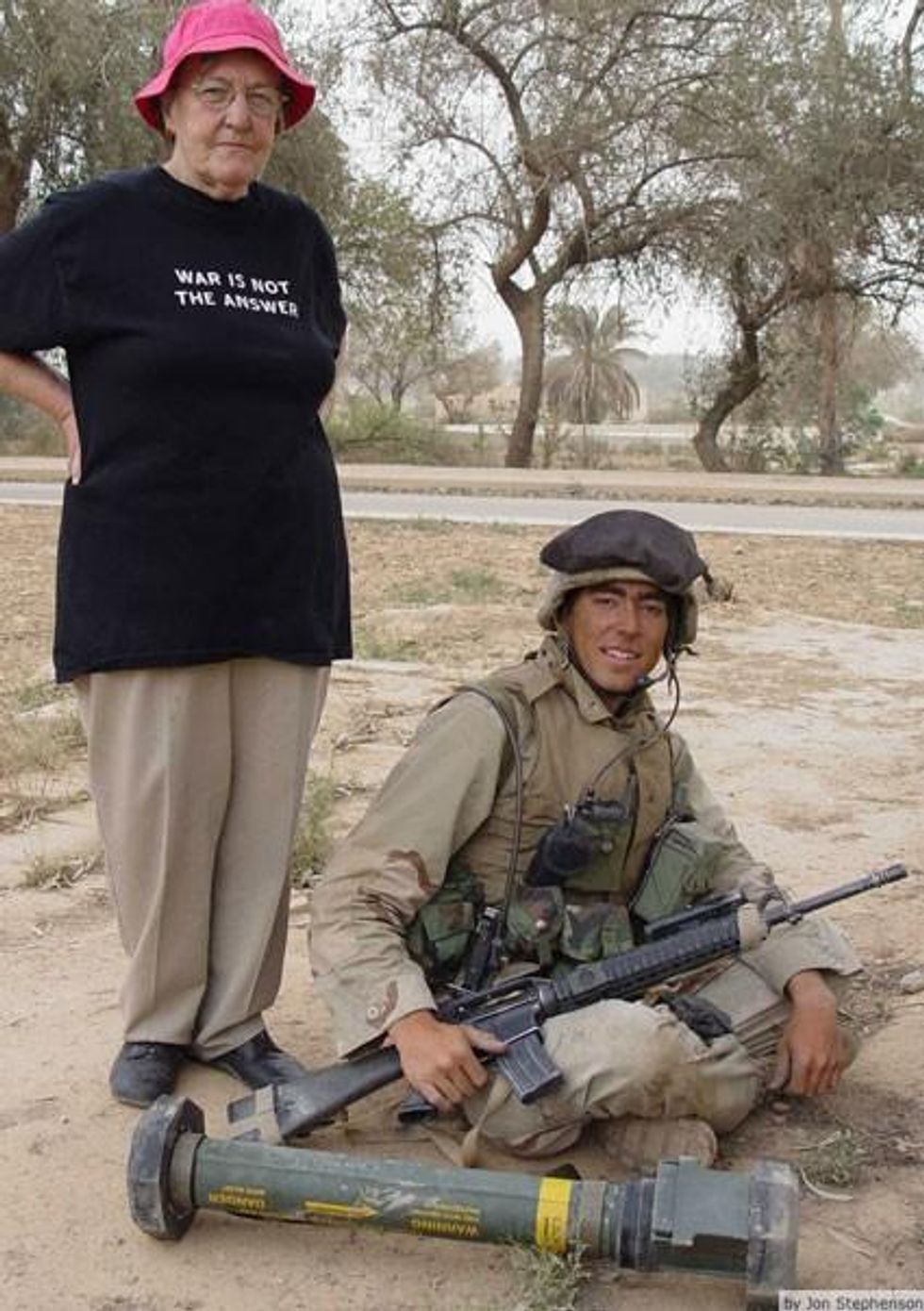

My mother, then in her eighties, was actually quite anti-war, but she was also against evil dictators, and the governance of any country where she was consistently told we might need to invade. If a war could be packaged as necessary to achieving humanitarian goals, then my mother would almost certainly join the majority of U.S. people, over the past decade or so, in tolerating wars or at least enduring them with a general indifference to any accounts of the human suffering the wars might cause.

Although the war in Afghanistan is often referred to as the longest war in U.S. history, the multistage war in Iraq, beginning in 1991 and inclusive of 13 years of continual bombardment and nightmarish, generation-wasting economic warfare waged through militarily-enforced sanctions, constitutes the longest war, one which in real terms is of course ongoing.

John Tirman, of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, attempted, in his book The Deaths of Others, (Oxford University Press, 2011), to understand how U.S. people could be so indifferent to the suffering caused by U.S. military actions. He was following up on his seminal study of Iraq war casualties, released by John Hopkins and printed in The Lancet, which had concluded that in the three and a half years following Shock and Awe, the war and its effects had killed upwards of 660,000 Iraqis. This credible report, backed by prestigious academic institutions, had been ignored by the government, and thus also by the media, allowing a disinterested public to avoid learning information they'd mostly been careful not to ask for.

In his book, Tirman was now trying to understand how the U.S. public could have been so indifferent.

His eventual explanation focuses on how hard U.S. war planners (and war profiteers) have worked to overcome "the Vietnam Syndrome," which is to say the healthy democratic rejection of the Vietnam War, which authorities across the liberal-to-conservative spectrum have tended to see as a sort of disease to be eliminated. The inoculation campaign had been very effective: By creating an all-volunteer army, by carefully regimenting and 'embedding' reporters and relentlessly emphasizing "humanitarian" goals to be achieved by any exercise of our power overseas, the U.S. military-industrial complex has been able to assure that the majority of U.S. people won't rise up in protest of our wars. If the public can be persuaded that a war is essentially humanitarian, Tirman believes their indifference can be counted on, in spite of the number of U.S. soldiers killed or maimed or psychologically disabled by their wartime experiences, regardless of the drain on U.S. economies however stricken or depressed, and without any apparent concern for or even awareness of the horrendous consequences borne by the communities overseas that are the targets of our massively armed humanitarianism. Adding to a predisposition on behalf of saving people from evil dictators, the U.S. population and that of many western allies face declining availability of jobs. Available jobs are increasingly controlled by either the military-industrial complex or the prison (criminal justice) industrial complex.

A few years ago, many people disenchanted with the Iraq and Afghan wars placed hopes in Obama as someone who would uphold the rule of law, including the international laws, ratified by U.S. congresses past, against international aggression and war crime, ending those abuses by the U.S. military, its private-sector contractors, and the CIA, which have contributed so to worldwide hostility against the U.S. and have arguably so greatly lessened our security. But the Obama administration, in its de facto continuation of both wars, in its massive escalation of targeted assassinations worldwide and its secrecy about drone warfare against Pakistan, has repeatedly shown our government's unshakeable allegiance, to militarists and those radically right-wing advocates of corporate power we're often now asked to call "centrists".

I think we in the peace and antiwar movements find ourselves stalemated. Groups are outspent and out-maneuvered by military and corporate institutions with power to undercut whatever "clout" our movements might have developed because these two complexes have now arrogated so much antidemocratic control over the media and the economy. Nonetheless, grassroots groups persist with arduous and often heroic efforts to continue educating their constituencies and reminding ordinary people that the defense industry is not providing them with any of the security that it assuredly isn't providing for people trapped in our war zones.

What direction should the peace and antiwar movements pursue now? Now, when it seems difficult to point toward substantial possible gains? Now, as the U.S. continues to wage multiple wars and build on a weapons stockpile that already exceeds the combined arsenals of the next most militarized eighteen countries on Earth? In advance or in retreat, we have to keep resisting. Surely, we must continue basic "maintenance" tasks of outreach and education. Voices for Creative Nonviolence tries to assist in educating the general public about people who bear the brunt of our wars - so we travel to war zones and live alongside ordinary people, trying, upon our return, to get their stories through to ordinary people in the U.S. We hope that by doing so we can eventually help motivate civil society into action to oppose these wars. But while working to preserve the heart of the society, its civilization in the best meaning of that term, we know we must always organize for and participate in campaigns designed to have the greatest possible impact on policymakers now, and through them on those whose lives are so desperately at stake. That commitment in turn is part of our message to our neighbors to reclaim their humanity through action.

It's not just each other's hearts, but also each other's minds that citizens of a democracy are called upon to exercise. We must constantly appeal to the rationality of the general public, engaging in humble dialogue so they can appeal to ours, helping people see that U.S. war making does not make people safer here or abroad, that in fact we are jeopardized as well - if only by the intense anger and frustration caused by policies like targeted assassination, night raids, and aerial bombings of civilians.

We should celebrate the tremendous accomplishment of Occupy Wall Street. In just twelve weeks the "99 and 1" logos reintroduced people, worldwide, to the normalness of discussing, in all manner of public discussions, the fundamental unfairness of systems designed to benefit small elites at the expense of vast majorities; and the OWS movement welcomed anyone and everyone into solidarity in building towards more humane, more just, and more democratic communities. The peace movement should participate in and encourage this remarkable network, and similar organizations that will spring up to complement it, not only to demand more jobs and better wages but also to stipulate what kinds of jobs we want and what kinds of products we want those jobs devoted to creating. We must campaign for jobs that build our society instead of converting it into junk - that produce constructive and necessary goods and services and above all not the weapons that we employ in prisons and battlefields at home and abroad.

We must think hard about ways to democratize our country, and reverse the "unwarranted influence" over our society which, half a century ago, a Republican president was warning us already belonged to the military industrial complex. Enormous sums of money, along with human ingenuity and resources, are now being poured into developing drone warfare and surveillance to be used abroad and increasingly at home, but the more intelligence our leaders collect, the less we, the led, have access to. The drones aren't there to help us understand the Afghan people - how they huddle together on the brink of starvation, dared to survive the capricious and uncivilized behavior of a nation gone mad on war. Have we any means of imposing civilization, not on desperate people around the world, but on those who lack it - the elites that control our military, our economy, and our government?

And honestly, I couldn't persuade my own mother. I should admit here to a recent conversation with my sisters, the oldest of whom recently shared, "We weren't sure whether or not to tell you, but mom really did hope you were working for the CIA."

We never know how we will influence others and what unexpected developments might happen. The destiny of a world of seven billion people should never be shaped by a few activists - as it currently is shaped by a remarkably few activists occupying the U.S. Pentagon, our business centers, and the White House. We're not supposed to make any change we can securely claim credit for - we're supposed to do good for the world - to speak truth to it, to resist its oppressors, to surprise it with decency, love, and an implacability for justice; and trust it to surprise us in turn.

With eyes wide open, willing to look in the mirror, (I'm drawing from the titles of two extraordinarily impressive campaigns designed by the American Friends Service Committee), we must persist with the tasks of education and outreach, looking for nonviolent means to take risks commensurate to the crimes being committed, all the while growing ever more open to links with popular movements and respectful alliances well outside our choir. We must civilize the world by examples of clear-sightedness and courage. We're supposed to do what anyone is supposed to do; live as full humans, as best we can, in a world whose destiny we can never predict, and whose astonishingly precious inhabitants could never be given enough justice, or love, or time.