Trump Is Rage Baiting the US Into a Second Civil War

In a healthy democracy, all sides generally recognize the legitimacy of the system itself, regardless of internal squabbles. In the United States, this is no longer the case.

A January 2026 Gallup poll showed that 89% of all Americans expect high levels of political conflict this year, as the country heads toward one of its most decisive midterm elections ever.

Gallup, however, was stating the obvious. It is a surprise that not all Americans feel this way, judging by the coarse, often outright racist discourse currently being normalized by top American officials. Some call this new rhetoric the "language of humiliation," where officials refer to entire social and racial groups as "vermin," "garbage," or "invaders."

The aim of this language is not simply to insult, but to feed the "Rage Bait Cycle"—tellingly, Oxford’s 2025 Word of the Year: A high-ranking official attacks a whole community or "the other side"; waits for a response; escalates the attacks; and then presents himself as a protector of traditions, values, and America itself. This does more than simply “hollow out” democracy, as suggested in a Human Rights Watch report last January; it prepares the country for “affective polarization,” where people no longer just disagree on political matters, but actively dislike each other for who they are and what they supposedly represent.

How else can we explain the statements of US President Donald Trump, who declared last December: “Somalia... is barely a country... Their country stinks and we don't want them in our country... We’re going to go the wrong way if we keep taking in garbage into our country. Ilhan Omar is garbage. She’s garbage. Her friends are garbage.” This is not simply an angry president, but an overreaching political discourse supported by millions of Americans who continue to see Trump as their defender and savior.

We are entering a state of regime cleavage—a political struggle no longer concerned with winning elections, but one where dominant groups fundamentally disagree on the very definition of what constitutes a nation.

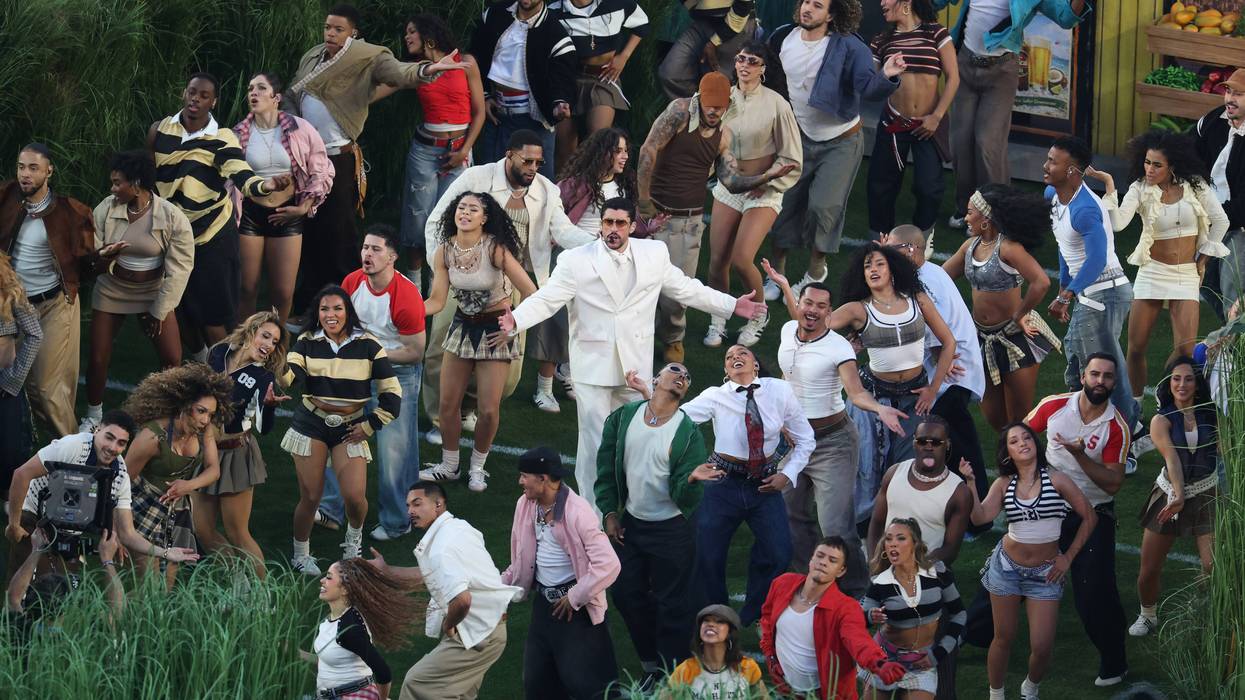

This polarization reached a fever pitch at the 2026 Super Bowl, where the halftime selection of Puerto Rican artist Bad Bunny ignited a firestorm over national identity. While millions celebrated the performance, Trump and conservative commentators launched a boycott, labeling the Spanish-language show “not American enough” and inappropriate. The rhetoric escalated further when Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem suggested Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents would be “all over” the event, effectively ostracizing countless people from their right to belong to a distinct culture within American society.

The weaponization of culture and language was not limited to the stage; it split American viewers into two distinct camps: those who watched the official performance and those who turned to an “All-American” alternative broadcast hosted by Turning Point USA featuring Kid Rock. This "countering" is the very essence of the American conflict, which many have rightly predicted will eventually reach a breaking point akin to civil war.

That conclusion seems inevitable as the culture war couples with three alarming trends: identity dehumanization; partisan mirroring—the view that the other side is an existential threat; and institutional conflict—where federal agencies are perceived as "lawless," sitting congresswomen are labeled "garbage," and dissenting views are branded as treasonous.

This takes us to the fundamental question of legitimacy. In a healthy democracy, all sides generally recognize the legitimacy of the system itself, regardless of internal squabbles. In the United States, this is no longer the case. We are entering a state of regime cleavage—a political struggle no longer concerned with winning elections, but one where dominant groups fundamentally disagree on the very definition of what constitutes a nation.

The current crisis is not a new phenomenon; it dates back to the historical tension between 'assimilation" within an American "melting pot" versus the "multiculturalism" often compared to a "salad bowl." The melting pot principle, frequently promoted as a positive social ideal, effectively pressures immigrant communities and minorities to "melt" into a white-Christian-dominated social structure. In contrast, the salad bowl model allows minorities to feel very much American while maintaining their distinct languages, customs, and social priorities, thus without losing their unique identities.

While this debate persisted for decades as a highly intellectualized academic exercise, it has transformed into a daily, visceral conflict. The 2026 Super Bowl served as a stark manifestation of this deeper cultural friction. Several factors have pushed the United States to this precipice: a struggling economy, rising social inequality, and a rapidly closing demographic gap. Dominant social groups no longer feel "safe." Although the perceived threat to their "way of life" is often framed as a cultural or social grievance, it is, in essence, a struggle over economic privilege and political dominance.

There is also a significant disparity in political focus. While the right—represented by the MAGA movement and TPUSA—possesses a clarity of vision and relative political cohesion, the "other side" remains shrouded in ambiguity. The Democratic institution, which purports to represent the grievances of all other marginalized groups, lacks the trust of younger Americans, particularly those belonging to Gen Z. According to a recent poll by the Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), trust in traditional political institutions among voters aged 18-25 has plummeted to historic lows, with over 65% expressing dissatisfaction with both major parties.

As the midterm elections approach, society is stretching its existing polarization to a new extreme. While the right clings to the hope of a savior making the country "great again," the "left" is largely governed by the politics of counter demonization and reactive grievances—hardly a revolutionary approach to governance.

Regardless of the November results, much of the outcome is already predetermined: a wider social conflict in the US is inevitable. The breaking point is fast approaching.