A 10-year-old child named Moyna bathes in the contaminated floodwaters surrounding her home in Bangladesh.

What Can We Do for the 250 Million and Counting Displaced by the Environmental Crisis?

We must demand a new comprehensive legal framework for climate refugees to safeguard vulnerable populations and protect those who may be at risk in the future.

The consequences of our planet's changing climate extend far beyond warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events. Human displacement as a result of the climate crisis is now one of the world's most pressing issues, as estimates predict that there could be more than 1 billion climate refugees by 2050.

The plight of these people is neglected and forgotten as they remain unprotected by the law and are excluded from international aid programs.

Climate refugees are forced to flee their homes as the environment degrades and climate-related disasters take hold. Climate change is now one of the leading causes of mass forced displacement.

Climate change is also increasing rates of poverty, instability, and violence—further drivers of migration.

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

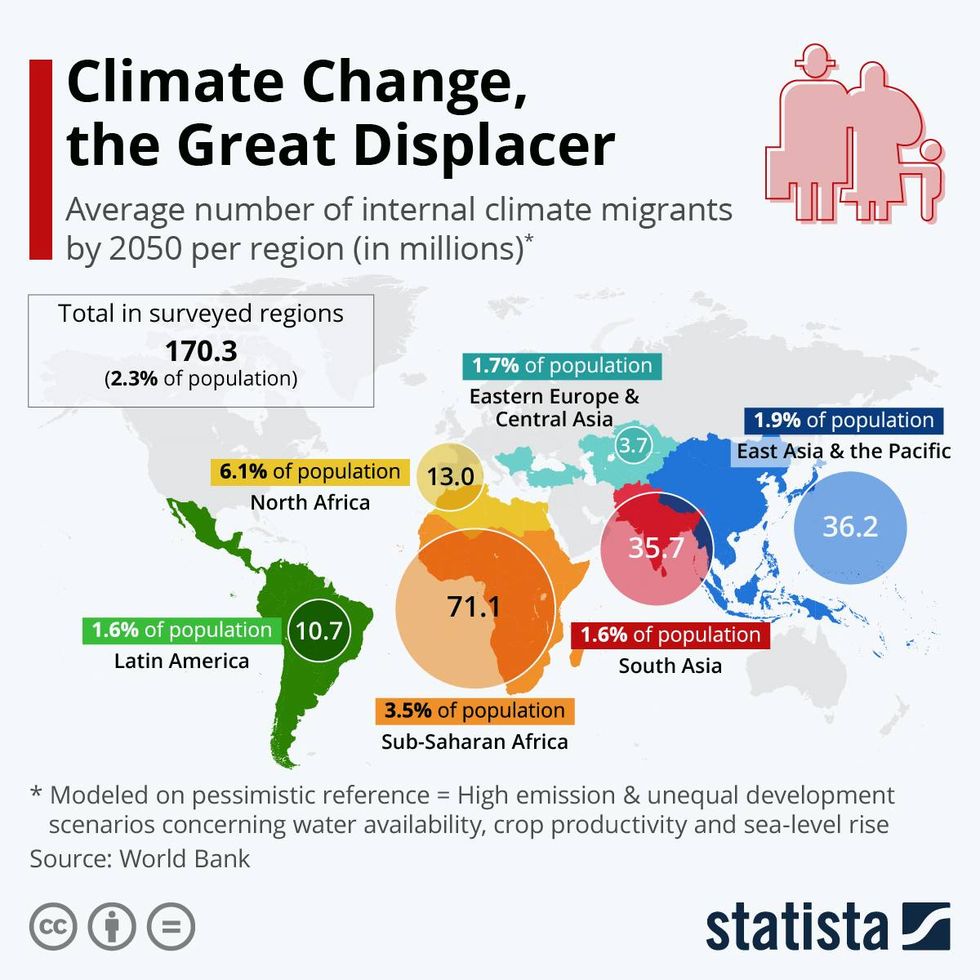

Those on the front lines of climate change are often in countries that contributed the least to it. The vast majority of climate migration is internal, which puts an unsustainable strain on the already limited resources of these nations.

"When people are driven out because their local environment has become uninhabitable, it might look like a process of nature, something inevitable... Yet the deteriorating climate is very often the result of poor choices and destructive activity, of selfishness and neglect," said Pope Francis.

A Humanitarian Crisis

- In 2022, climate-related disasters accounted for more than half of new reported displacements.

- Almost 60% of existing refugees and IDPs live in countries that are among the most vulnerable to climate change.

- The demand for humanitarian assistance due to climate-related disasters is predicted to double by 2050.

- In 2023, the countries with the highest numbers of new internal displacements (IDPs) due to environmental disasters were China, Türkiye, the Philippines, Somalia, and Bangladesh.

- Three out of four refugees and displaced people are in countries experiencing both conflict and high risk of climate hazards.

- By 2030, water scarcity could displace 700 million people.

- Up to 75% of Bangladesh sits below sea level. Rising water levels have already affected 25.9 million people.

- Unpredictable rainfall patterns, desertification, and declining agricultural productivity undermine rural livelihoods and force migration to urban areas.

- Climate change perpetuates poverty. The World Bank estimates that without urgent action, an additional 32 -132 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty by 2030.

- Climate migration is not just an issue in developing countries. In 2022, 3.2 million people were either displaced or evacuated due to wildfires, floods, and hurricanes in the US.

- Within Europe, rising sea levels are expected to displace 1.6-5.3 million people by the end of the century.

Expansion of Legal Protections

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

The Refugee Convention, which entered into force in 1954, was established to protect those who had fled persecution from the atrocities of World War II. Its protections extend only to those who must leave their home countries due to war, violence, conflict, or any other kind of maltreatment. It also does not protect those who have been displaced in their own countries.

As the vast majority of climate refugees are not crossing borders nor fleeing violence, their status is outside of the convention's reach. These facts do not mean that these people are less in need of assistance or that their lives are not equally in danger, yet the law overlooks their plight.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

Refugee advocates are pushing for an expansion to the convention to include the rights of those forced to move due to environmental factors, but have met with significant political pushback. Critics argue it would lead to the weakening of protection for those experiencing serious persecution. The difficulty in proving the causal factors of climate migration is a further barrier.

The 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement help bridge the gap in protecting climate refugees; however, its nonbinding nature limits its practical effect and gives it no legal force. It also does not protect those who must cross borders.

The Global Compact for Migration was adopted in 2018. It was the first United Nations framework on international migration. For the first time, climate change was officially recognized as a driver of migration, but it still does not grant legal protection for climate refugees. Instead, the compact promotes safe, orderly pathways for migrants, including planned relocation, visa options, and humanitarian shelter.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is both the process and the treaty that help countries mitigate the causes and consequences of the climate crisis. It was signed by 154 countries in 1992. Climate migrants aren't explicitly protected by the UNFCCC.

As it stands, although some countries have enacted domestic laws that provide temporary protection for climate refugees, the lack of recognition under the Refugee Convention means there is still no international, legally binding mechanism for them.

Countries are reluctant to sign up to yet another agreement, especially as it may make them responsible for climate migrants who arrive at their borders and promote larger migrant influxes to favored countries. There are many political obstacles which ultimately exacerbate the humanitarian needs of millions.

We must begin to address internal climate displacement in the most vulnerable countries. Tackling the issue at its root is imperative, and the nations historically responsible for the damage must be made to pay.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

The Loss and Damage Fund was established in 2022 at COP27 to address the financial needs of communities severely impacted by climate change. The money would support rehabilitation, recovery, and human mobility. While a brilliant initiative, as of late 2025, rich nations have delivered less than half of what they initially committed to the fund.

Climate Justice is Migrant Justice

The climate justice movement recognizes that climate change disproportionately affects marginalized and vulnerable communities. It demands that the Global North, which has massive historical accountability, should bear the burden of the solutions. The movement brings social justice, racial justice, human rights, and economic equality into the climate debate.

In July 2025, years of activism by a bold group of law students from the University of the South Pacific paid off. The Vanuatu ICJ Initiative spearheaded legal action that led to a historic advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The following was adopted unanimously by all 15 judges: Nations have a legal duty to combat the planetary crisis.

The ICJ has, for the first time, officially categorized the climate crisis as an "urgent and existential threat" and emphasized that "cooperation is not a matter of choice for states but a pressing need and a legal obligation." The ICJ opinion can now be used to demand more ambitious climate protection measures, to ensure compliance with the Paris Agreement, to implement national and international climate laws, and potentially to help protect climate migrants.

The initiative also highlighted the vulnerability of small island nations and demonstrated that collective action and legal accountability are essential tools on the journey to justice and sustainable development.

Any justice for climate-induced migration must be human-rights focused. Humanitarian visas, temporary protection, authorization to stay, and bilateral free movement agreements would all help to ease the suffering of those forced to leave their homes.

Invisible No Longer

"When we refugees are excluded, our voices are silenced, our experiences go unheard, and the reality of the climate situation in the Global South is blurred" says Ugandan climate justice activist Ayebare Denise.

Climate migrants have remained invisible in climate and migration debates for years. The International Organisation for Migration have been working hard to bring climatic and environmental factors into the spotlight. They are establishing a body of evidence that will definitively prove that climate change, both directly and indirectly, affects human mobility.

The UN Refugee Agency advocates for states' responsibilities and obligations to address the migration crisis caused by climate change. They view climate change as a threat multiplier and are working toward protection frameworks.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees.

The debate over establishing a climate refugee status is ongoing, and while a legal definition would be helpful, it would be only a partial solution. The vast majority of climate migrants do not want to leave their homes, their livelihoods, or their communities. Admittedly, this is no easy feat, but we must fix the root of the problem—climate change itself.

Without urgent action, we are all at risk of becoming climate refugees.

While working to address immediate needs, climate discussions should continue to focus on preventive measures. Climate mitigation, adaptation, and a just energy transition are essential.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees. We must demand a new comprehensive legal framework for climate refugees to safeguard vulnerable populations and protect those who may be at risk in the future.

Supporting climate refugees is our moral obligation.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The consequences of our planet's changing climate extend far beyond warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events. Human displacement as a result of the climate crisis is now one of the world's most pressing issues, as estimates predict that there could be more than 1 billion climate refugees by 2050.

The plight of these people is neglected and forgotten as they remain unprotected by the law and are excluded from international aid programs.

Climate refugees are forced to flee their homes as the environment degrades and climate-related disasters take hold. Climate change is now one of the leading causes of mass forced displacement.

Climate change is also increasing rates of poverty, instability, and violence—further drivers of migration.

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

Those on the front lines of climate change are often in countries that contributed the least to it. The vast majority of climate migration is internal, which puts an unsustainable strain on the already limited resources of these nations.

"When people are driven out because their local environment has become uninhabitable, it might look like a process of nature, something inevitable... Yet the deteriorating climate is very often the result of poor choices and destructive activity, of selfishness and neglect," said Pope Francis.

A Humanitarian Crisis

- In 2022, climate-related disasters accounted for more than half of new reported displacements.

- Almost 60% of existing refugees and IDPs live in countries that are among the most vulnerable to climate change.

- The demand for humanitarian assistance due to climate-related disasters is predicted to double by 2050.

- In 2023, the countries with the highest numbers of new internal displacements (IDPs) due to environmental disasters were China, Türkiye, the Philippines, Somalia, and Bangladesh.

- Three out of four refugees and displaced people are in countries experiencing both conflict and high risk of climate hazards.

- By 2030, water scarcity could displace 700 million people.

- Up to 75% of Bangladesh sits below sea level. Rising water levels have already affected 25.9 million people.

- Unpredictable rainfall patterns, desertification, and declining agricultural productivity undermine rural livelihoods and force migration to urban areas.

- Climate change perpetuates poverty. The World Bank estimates that without urgent action, an additional 32 -132 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty by 2030.

- Climate migration is not just an issue in developing countries. In 2022, 3.2 million people were either displaced or evacuated due to wildfires, floods, and hurricanes in the US.

- Within Europe, rising sea levels are expected to displace 1.6-5.3 million people by the end of the century.

Expansion of Legal Protections

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

The Refugee Convention, which entered into force in 1954, was established to protect those who had fled persecution from the atrocities of World War II. Its protections extend only to those who must leave their home countries due to war, violence, conflict, or any other kind of maltreatment. It also does not protect those who have been displaced in their own countries.

As the vast majority of climate refugees are not crossing borders nor fleeing violence, their status is outside of the convention's reach. These facts do not mean that these people are less in need of assistance or that their lives are not equally in danger, yet the law overlooks their plight.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

Refugee advocates are pushing for an expansion to the convention to include the rights of those forced to move due to environmental factors, but have met with significant political pushback. Critics argue it would lead to the weakening of protection for those experiencing serious persecution. The difficulty in proving the causal factors of climate migration is a further barrier.

The 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement help bridge the gap in protecting climate refugees; however, its nonbinding nature limits its practical effect and gives it no legal force. It also does not protect those who must cross borders.

The Global Compact for Migration was adopted in 2018. It was the first United Nations framework on international migration. For the first time, climate change was officially recognized as a driver of migration, but it still does not grant legal protection for climate refugees. Instead, the compact promotes safe, orderly pathways for migrants, including planned relocation, visa options, and humanitarian shelter.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is both the process and the treaty that help countries mitigate the causes and consequences of the climate crisis. It was signed by 154 countries in 1992. Climate migrants aren't explicitly protected by the UNFCCC.

As it stands, although some countries have enacted domestic laws that provide temporary protection for climate refugees, the lack of recognition under the Refugee Convention means there is still no international, legally binding mechanism for them.

Countries are reluctant to sign up to yet another agreement, especially as it may make them responsible for climate migrants who arrive at their borders and promote larger migrant influxes to favored countries. There are many political obstacles which ultimately exacerbate the humanitarian needs of millions.

We must begin to address internal climate displacement in the most vulnerable countries. Tackling the issue at its root is imperative, and the nations historically responsible for the damage must be made to pay.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

The Loss and Damage Fund was established in 2022 at COP27 to address the financial needs of communities severely impacted by climate change. The money would support rehabilitation, recovery, and human mobility. While a brilliant initiative, as of late 2025, rich nations have delivered less than half of what they initially committed to the fund.

Climate Justice is Migrant Justice

The climate justice movement recognizes that climate change disproportionately affects marginalized and vulnerable communities. It demands that the Global North, which has massive historical accountability, should bear the burden of the solutions. The movement brings social justice, racial justice, human rights, and economic equality into the climate debate.

In July 2025, years of activism by a bold group of law students from the University of the South Pacific paid off. The Vanuatu ICJ Initiative spearheaded legal action that led to a historic advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The following was adopted unanimously by all 15 judges: Nations have a legal duty to combat the planetary crisis.

The ICJ has, for the first time, officially categorized the climate crisis as an "urgent and existential threat" and emphasized that "cooperation is not a matter of choice for states but a pressing need and a legal obligation." The ICJ opinion can now be used to demand more ambitious climate protection measures, to ensure compliance with the Paris Agreement, to implement national and international climate laws, and potentially to help protect climate migrants.

The initiative also highlighted the vulnerability of small island nations and demonstrated that collective action and legal accountability are essential tools on the journey to justice and sustainable development.

Any justice for climate-induced migration must be human-rights focused. Humanitarian visas, temporary protection, authorization to stay, and bilateral free movement agreements would all help to ease the suffering of those forced to leave their homes.

Invisible No Longer

"When we refugees are excluded, our voices are silenced, our experiences go unheard, and the reality of the climate situation in the Global South is blurred" says Ugandan climate justice activist Ayebare Denise.

Climate migrants have remained invisible in climate and migration debates for years. The International Organisation for Migration have been working hard to bring climatic and environmental factors into the spotlight. They are establishing a body of evidence that will definitively prove that climate change, both directly and indirectly, affects human mobility.

The UN Refugee Agency advocates for states' responsibilities and obligations to address the migration crisis caused by climate change. They view climate change as a threat multiplier and are working toward protection frameworks.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees.

The debate over establishing a climate refugee status is ongoing, and while a legal definition would be helpful, it would be only a partial solution. The vast majority of climate migrants do not want to leave their homes, their livelihoods, or their communities. Admittedly, this is no easy feat, but we must fix the root of the problem—climate change itself.

Without urgent action, we are all at risk of becoming climate refugees.

While working to address immediate needs, climate discussions should continue to focus on preventive measures. Climate mitigation, adaptation, and a just energy transition are essential.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees. We must demand a new comprehensive legal framework for climate refugees to safeguard vulnerable populations and protect those who may be at risk in the future.

Supporting climate refugees is our moral obligation.

- 'Against Humanity': Leaders Denounce Fossil Fuel-Loving Trump as He Skips Out on Global Climate Summit ›

- Why I Brought My Toddler to Protest at Citi CEO Jane Fraser’s House ›

- Forced Displacement Exposes Gaps in Climate Migration Responses ›

- To Force Radical Climate Action, the Global South Should De-Link From Western Capitalism ›

The consequences of our planet's changing climate extend far beyond warming temperatures, rising sea levels, and extreme weather events. Human displacement as a result of the climate crisis is now one of the world's most pressing issues, as estimates predict that there could be more than 1 billion climate refugees by 2050.

The plight of these people is neglected and forgotten as they remain unprotected by the law and are excluded from international aid programs.

Climate refugees are forced to flee their homes as the environment degrades and climate-related disasters take hold. Climate change is now one of the leading causes of mass forced displacement.

Climate change is also increasing rates of poverty, instability, and violence—further drivers of migration.

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

Those on the front lines of climate change are often in countries that contributed the least to it. The vast majority of climate migration is internal, which puts an unsustainable strain on the already limited resources of these nations.

"When people are driven out because their local environment has become uninhabitable, it might look like a process of nature, something inevitable... Yet the deteriorating climate is very often the result of poor choices and destructive activity, of selfishness and neglect," said Pope Francis.

A Humanitarian Crisis

- In 2022, climate-related disasters accounted for more than half of new reported displacements.

- Almost 60% of existing refugees and IDPs live in countries that are among the most vulnerable to climate change.

- The demand for humanitarian assistance due to climate-related disasters is predicted to double by 2050.

- In 2023, the countries with the highest numbers of new internal displacements (IDPs) due to environmental disasters were China, Türkiye, the Philippines, Somalia, and Bangladesh.

- Three out of four refugees and displaced people are in countries experiencing both conflict and high risk of climate hazards.

- By 2030, water scarcity could displace 700 million people.

- Up to 75% of Bangladesh sits below sea level. Rising water levels have already affected 25.9 million people.

- Unpredictable rainfall patterns, desertification, and declining agricultural productivity undermine rural livelihoods and force migration to urban areas.

- Climate change perpetuates poverty. The World Bank estimates that without urgent action, an additional 32 -132 million people could be pushed into extreme poverty by 2030.

- Climate migration is not just an issue in developing countries. In 2022, 3.2 million people were either displaced or evacuated due to wildfires, floods, and hurricanes in the US.

- Within Europe, rising sea levels are expected to displace 1.6-5.3 million people by the end of the century.

Expansion of Legal Protections

Climate migrants remain in a murky legal space that neither recognizes nor protects them. In fact, the term is not recognized at all in international law.

The Refugee Convention, which entered into force in 1954, was established to protect those who had fled persecution from the atrocities of World War II. Its protections extend only to those who must leave their home countries due to war, violence, conflict, or any other kind of maltreatment. It also does not protect those who have been displaced in their own countries.

As the vast majority of climate refugees are not crossing borders nor fleeing violence, their status is outside of the convention's reach. These facts do not mean that these people are less in need of assistance or that their lives are not equally in danger, yet the law overlooks their plight.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

Refugee advocates are pushing for an expansion to the convention to include the rights of those forced to move due to environmental factors, but have met with significant political pushback. Critics argue it would lead to the weakening of protection for those experiencing serious persecution. The difficulty in proving the causal factors of climate migration is a further barrier.

The 1998 Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement help bridge the gap in protecting climate refugees; however, its nonbinding nature limits its practical effect and gives it no legal force. It also does not protect those who must cross borders.

The Global Compact for Migration was adopted in 2018. It was the first United Nations framework on international migration. For the first time, climate change was officially recognized as a driver of migration, but it still does not grant legal protection for climate refugees. Instead, the compact promotes safe, orderly pathways for migrants, including planned relocation, visa options, and humanitarian shelter.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is both the process and the treaty that help countries mitigate the causes and consequences of the climate crisis. It was signed by 154 countries in 1992. Climate migrants aren't explicitly protected by the UNFCCC.

As it stands, although some countries have enacted domestic laws that provide temporary protection for climate refugees, the lack of recognition under the Refugee Convention means there is still no international, legally binding mechanism for them.

Countries are reluctant to sign up to yet another agreement, especially as it may make them responsible for climate migrants who arrive at their borders and promote larger migrant influxes to favored countries. There are many political obstacles which ultimately exacerbate the humanitarian needs of millions.

We must begin to address internal climate displacement in the most vulnerable countries. Tackling the issue at its root is imperative, and the nations historically responsible for the damage must be made to pay.

Climate migration is a form of adaptation. We can build new pathways for safe and regular migration.

The Loss and Damage Fund was established in 2022 at COP27 to address the financial needs of communities severely impacted by climate change. The money would support rehabilitation, recovery, and human mobility. While a brilliant initiative, as of late 2025, rich nations have delivered less than half of what they initially committed to the fund.

Climate Justice is Migrant Justice

The climate justice movement recognizes that climate change disproportionately affects marginalized and vulnerable communities. It demands that the Global North, which has massive historical accountability, should bear the burden of the solutions. The movement brings social justice, racial justice, human rights, and economic equality into the climate debate.

In July 2025, years of activism by a bold group of law students from the University of the South Pacific paid off. The Vanuatu ICJ Initiative spearheaded legal action that led to a historic advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

The following was adopted unanimously by all 15 judges: Nations have a legal duty to combat the planetary crisis.

The ICJ has, for the first time, officially categorized the climate crisis as an "urgent and existential threat" and emphasized that "cooperation is not a matter of choice for states but a pressing need and a legal obligation." The ICJ opinion can now be used to demand more ambitious climate protection measures, to ensure compliance with the Paris Agreement, to implement national and international climate laws, and potentially to help protect climate migrants.

The initiative also highlighted the vulnerability of small island nations and demonstrated that collective action and legal accountability are essential tools on the journey to justice and sustainable development.

Any justice for climate-induced migration must be human-rights focused. Humanitarian visas, temporary protection, authorization to stay, and bilateral free movement agreements would all help to ease the suffering of those forced to leave their homes.

Invisible No Longer

"When we refugees are excluded, our voices are silenced, our experiences go unheard, and the reality of the climate situation in the Global South is blurred" says Ugandan climate justice activist Ayebare Denise.

Climate migrants have remained invisible in climate and migration debates for years. The International Organisation for Migration have been working hard to bring climatic and environmental factors into the spotlight. They are establishing a body of evidence that will definitively prove that climate change, both directly and indirectly, affects human mobility.

The UN Refugee Agency advocates for states' responsibilities and obligations to address the migration crisis caused by climate change. They view climate change as a threat multiplier and are working toward protection frameworks.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees.

The debate over establishing a climate refugee status is ongoing, and while a legal definition would be helpful, it would be only a partial solution. The vast majority of climate migrants do not want to leave their homes, their livelihoods, or their communities. Admittedly, this is no easy feat, but we must fix the root of the problem—climate change itself.

Without urgent action, we are all at risk of becoming climate refugees.

While working to address immediate needs, climate discussions should continue to focus on preventive measures. Climate mitigation, adaptation, and a just energy transition are essential.

Countries must begin cooperating on this global issue and ensure the fair treatment of all refugees. We must demand a new comprehensive legal framework for climate refugees to safeguard vulnerable populations and protect those who may be at risk in the future.

Supporting climate refugees is our moral obligation.

- 'Against Humanity': Leaders Denounce Fossil Fuel-Loving Trump as He Skips Out on Global Climate Summit ›

- Why I Brought My Toddler to Protest at Citi CEO Jane Fraser’s House ›

- Forced Displacement Exposes Gaps in Climate Migration Responses ›

- To Force Radical Climate Action, the Global South Should De-Link From Western Capitalism ›