August, 27 2012, 03:58pm EDT

For Immediate Release

Contact:

Alan Barber, (202) 293-5380 x115

Private Equity and Breach of Trust

WASHINGTON

Though private equity firms have garnered much more attention recently, the focus has mainly been on how partners in these firms use tax loopholes to amass vast fortunes in part by not paying their fair share of taxes. Much less is known about the sources of these earnings. A new report from the Center for Economic and Policy Research sheds light on this process.

PE firms raise capital from investors - pension funds, mutual funds, insurance companies, university endowments, foundations and wealthy individuals - to acquire a portfolio of companies. The leveraged buyout of a company entails extensive debt financing, with the acquired company - not the PE firm - required to put up its assets as collateral for these debts and to repay the loan. The overriding goal of private equity is to manage its portfolio of companies to maximize returns for itself and its investors. Little is known about how the portfolio companies fare. PE firms claim that their profits come from adding value via better business strategies and operational improvements, and then selling these companies for more than they paid to acquire them. This is one way that PE can create value. But this is not the only, and often not the main, source of PE gains. PE firms have strong incentives to increase their own returns by redistributing wealth from other stakeholders to themselves.

As CEPR economist Eileen Appelbaum, one of the study's coauthors observes, "Private equity does sometimes use its superior access to capital markets and managerial know-how to improve efficiency in the operating companies it acquires. But often the gains that PE firms reap for themselves and their investors result not from the creation of wealth but from transfers from workers, tax payers, portfolio companies and creditors. Economists criticize this as 'rent-seeking' rather than 'profit-seeking' behavior. Breach of trust with stakeholders in the companies they acquire undermines the ability of these companies to create value and, in the worst case, threatens the company's very survival."

In pursuit of maximum profit, a company's new PE owners may be willing to default on the implicit contracts with workers, vendors, suppliers, creditors and others that ensured that the acquired company's stakeholders worked together productively and that were a major source of the economic value created by the company. This breach of trust with other stakeholders was identified as a potential source of shareholder returns in the leveraged buyout wave of the 1980s by Andrei Shleifer and Larry Summers. The report "Implications of Financial Capitalism for Employment Relations Research," examines four contemporary cases in which the private equity owners sought to quickly increase profits by reneging on implicit contracts. The cases demonstrate how PE firms breach implicit contracts in the context of other strategies PE uses to maximize investor returns. The report examines how this process plays out for stakeholders in very varied settings. The U.S. department store chain Mervyn's saw vendors, workers, creditors and the firm itself suffer losses after its buyout. When EMI Music Corporation was bought out, artists, managers, creditors and the firm were economically undermined. The New York rent-controlled complexes Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village saw renters and creditors lose millions. Finally, in the case of British confectioner Cadbury's, traditional industrial communities face massive layoffs despite assurances to the contrary. These very different cases show the similarities across industries in the mechanisms PE uses to make money.

The analysis challenges the agency theory view that the high levels of debt levered on portfolio companies leads managers of these companies to make better decisions, and that leveraged buyouts increase the profits of acquired companies through a better alignment of the interests of shareholders and managers. The cases presented in "Implications of Financial Capitalism for Employment Relations Research" illustrate how the use of portfolio companies' assets as security for these loans exposes these assets and, in turn, employees and former employees to risk in leveraged buyouts. The necessity to service debt or face bankruptcy allows the new owners to break implicit contracts to meet debt obligations, undermining the relationships among managers, workers, suppliers, and local communities. The earnings of PE owners may come at the expense of other stakeholders rather than from an increase in efficiency, and the future of the portfolio company may be put at risk.

An important aspect of the financialization of the U.S. economy has been the rise over the past three decades of new financial intermediaries - private equity firms, hedge fund firms and sovereign wealth funds - that raise private pools of capital and provide an alternative investment mechanism to the traditional banking system. The growth of these funds and the implications of their business models for firms and employees are examined in another report, "Financial Intermediaries in the United States." Attitudes of these investors towards unions vary from hostile to pragmatic to indifferent. As long as unions don't get in the way of making anticipated returns, these financial intermediaries can live with them. Whether attitudes are hostile or not, however, the lion's share of the wealth created by the productive enterprises in which these funds invest goes to investors while workers are left with less secure employment and lower pay and benefits.

The Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) was established in 1999 to promote democratic debate on the most important economic and social issues that affect people's lives. In order for citizens to effectively exercise their voices in a democracy, they should be informed about the problems and choices that they face. CEPR is committed to presenting issues in an accurate and understandable manner, so that the public is better prepared to choose among the various policy options.

(202) 293-5380LATEST NEWS

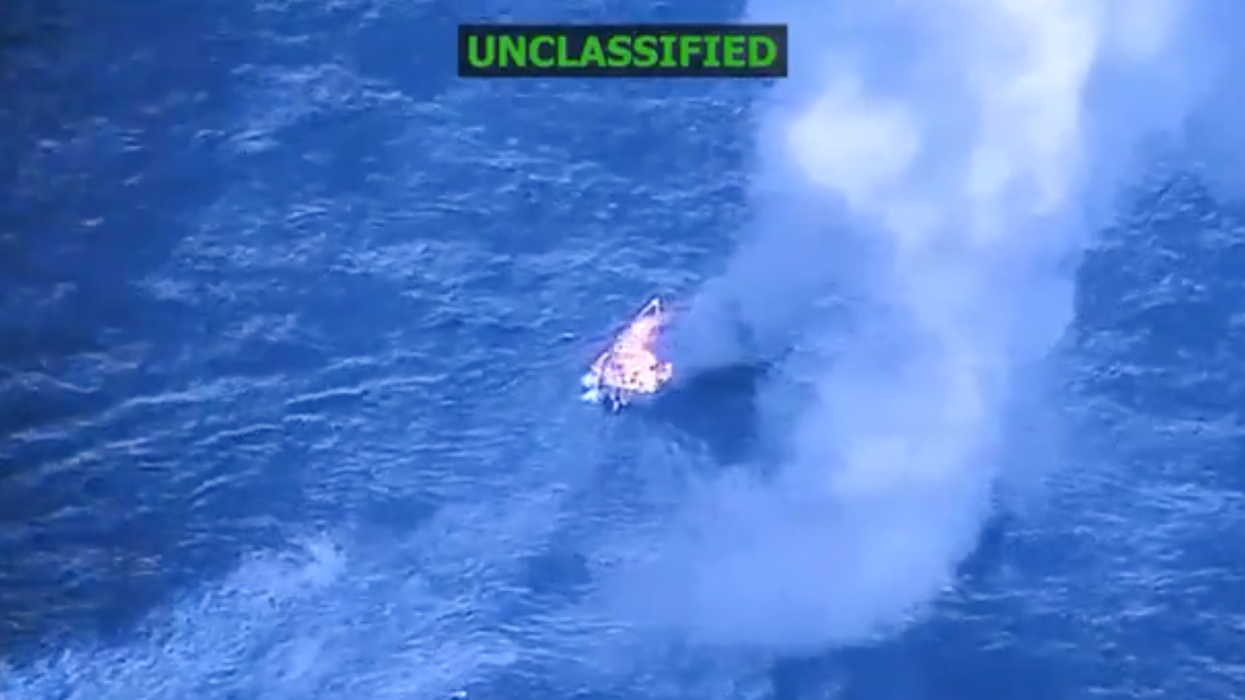

Second US Strike on Boat Attack Survivors Was Illegal—But Experts Stress That the Rest Were, Too

"It is blatantly illegal to order criminal suspects to be murdered rather than detained," said one human rights leader.

Dec 02, 2025

As the White House claims that President Donald Trump "has the authority" to blow up anyone he dubs a "narco-terrorist" and Adm. Frank M. "Mitch" Bradley prepares for a classified congressional briefing amid outrage over a double-tap strike that kicked off the administration's boat bombing spree, rights advocates and legal experts emphasize that all of the US attacks on alleged drug-running vessels have been illegal.

"Trump said he will look into reports that the US military (illegally) conducted a follow-up strike on a boat in the Caribbean that it believed to be ferrying drugs, killing survivors of an initial missile attack. But the initial attack was illegal too," Kenneth Roth, the former longtime director of the advocacy group Human Rights Watch, said on social media Monday.

Roth and various others have called out the US military's bombings of boats in the Caribbean and Pacific as unlawful since they began on September 2, when the two strikes killed 11 people. The Trump administration has confirmed its attacks on 22 vessels with a death toll of at least 83 people.

Shortly after the first bombing, the Intercept reported that some passengers initially survived but were killed in a follow-up attack. Then, the Washington Post and CNN reported Friday that Bradley ordered the second strike to comply with an alleged spoken directive from Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth to kill everyone on board.

The administration has not denied that the second strike killed survivors, but Hegseth and the White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, have insisted that the Pentagon chief never gave the spoken order.

However, the reporting has sparked reminders that all of the bombings are "war crimes, murder, or both," as the Former Judge Advocates General (JAGs) Working Group put it on Saturday.

Following Leavitt's remarks about the September 2 strikes during a Monday press briefing, Roth stressed Tuesday that "it is not 'self-defense' to return and kill two survivors of a first attack on a supposed drug boat as they clung to the wreckage. It is murder. No amount of Trump spin will change that."

"Whether Hegseth ordered survivors killed after a US attack on a supposed drug boat is not the heart of the matter," Roth said. "It is blatantly illegal to order criminal suspects to be murdered rather than detained. There is no 'armed conflict' despite Trump's claim."

The Trump administration has argued to Congress that the strikes on boats supposedly smuggling narcotics are justified because the United States is in an "armed conflict" with drug cartels that the president has labeled terrorist organizations.

During a Sunday appearance on ABC News' "This Week," US Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Md.) said that "I think it's very possible there was a war crime committed. Of course, for it to be a war crime, you have to accept the Trump administration's whole construct here... which is we're in armed conflict, at war... with the drug gangs."

"Of course, they've never presented the public with the information they've got here," added Van Hollen, a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. "But it could be worse than that. If that theory is wrong, then it's plain murder."

Michael Schmitt, a former Air Force lawyer and professor emeritus at the US Naval War College, rejects the Trump administration's argument that it is at war with cartels. Under international human rights law, he told the Associated Press on Monday, "you can only use lethal force in circumstances where there is an imminent threat," and with the first attack, "that wasn't the case."

"I can't imagine anyone, no matter what the circumstance, believing it is appropriate to kill people who are clinging to a boat in the water... That is clearly unlawful," Schmitt said. Even if the US were in an actual armed conflict, he explained, "it has been clear for well over a century that you may not declare what's called 'no quarter'—take no survivors, kill everyone."

According to the AP:

Brian Finucane, a senior adviser with the International Crisis Group and a former State Department lawyer, agreed that the US is not in an armed conflict with drug cartels.

"The term for a premeditated killing outside of armed conflict is murder," Finucane said, adding that US military personnel could be prosecuted in American courts.

"Murder on the high seas is a crime," he said. "Conspiracy to commit murder outside of the United States is a crime. And under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, Article 118 makes murder an offense."

Finucane also participated in a related podcast discussion released in October by Just Security, which on Monday published an analysis by three experts who examined "the law that applies to the alleged facts of the operation and Hegseth's reported order."

Michael Schmitt, Ryan Goodman, and Tess Bridgeman emphasized in Just Security that the law of armed conflict (LOAC) did not apply to the September 2 strikes because "the United States is not in an armed conflict with any drug trafficking cartel or criminal gang anywhere in the Western Hemisphere... For the same reason, the individuals involved have not committed war crimes."

"However, the duty to refuse clearly unlawful orders—such as an order to commit a crime—is not limited to armed conflict situations to which LOAC applies," they noted. "The alleged Hegseth order and special forces' lethal operation amounted to unlawful 'extrajudicial killing' under human rights law... The federal murder statute would also apply, whether or not there is an armed conflict."

Goodman added on social media Monday that the 11 people killed on September 2 "would be civilians even if this were an armed conflict... It's not even an armed conflict. It's extrajudicial killing."

Keep ReadingShow Less

As Prices Soar, Trump Denounces 'Affordability' as 'Democrat Scam'

"The president is trying to gaslight Americans into believing that everything is fine."

Dec 02, 2025

President Donald Trump on Tuesday blew off US voters' concerns about affordability, even as polls show most voters blame him for increasing prices on staple goods.

At the start of a Cabinet meeting, Trump falsely claimed that electricity prices are coming down, despite the fact that Americans across the country are struggling with utility bills being driven higher in large part by energy-devouring artificial intelligence data centers.

The president then claimed more broadly that voter concerns about increased costs were all figments of their imaginations.

"The word 'affordability' is a Democrat scam," Trump declared. "They say it and they go onto the next subject, and everyone thinks, 'Oh they had lower prices.' No, they had the worst inflation in the history of our country. Now, some people will correct me, because they always love to correct me, even though I'm right about everything. But some people like to correct me, and they say, '48 years.' I say it's not 48 years, it's much more, but they say it's the worst inflation we've had in 48 years, I'd say, ever."

Trump: But the word "Affordability" is a Democrat scam. pic.twitter.com/WmXeDLWQ0X

— Acyn (@Acyn) December 2, 2025

Later in the Cabinet meeting, a reporter asked Trump if he believed voters were growing "impatient" with his policies, which have not produced the kind of broad-based decline in prices he once promised.

Trump, however, doubled down.

"I think they're getting fake news from guys like you," he said. "Look, affordability is a hoax that was started by Democrats, who caused the problem of pricing."

Q: You talk about affordability. Are the American people getting impatient with the reforms you're making?

TRUMP: I think they're getting fake news from guys like you. Look, affordability is a hoax that was started by Democrats. pic.twitter.com/EhtSaKHEMk

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) December 2, 2025

The president's claims about affordability being a "scam" issue are at odds with what US voters are telling pollsters, however.

A Yahoo/YouGov poll released late last month, for instance, found 49% of Americans say that Trump's policies have done more to raise prices in the last year, compared with just 24% who say that he's lowered their costs. The survey also found voters are more likely to blame Trump for higher prices than they are to blame former President Joe Biden.

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Trump routinely campaigned on affordability and vowed to start lowering the cost of groceries starting on the very first day of his presidency. Since then, however, Trump has slapped heavy tariffs on a wide range of imported goods, which economists say have led to further price increases.

Many Democrats were quick to pounce on the president declaring affordability a "scam."

"There you have it folks," wrote Rep. Darren Soto (D-Fla.) on X. "From 'I will lower prices on Day 1' to this."

Rep. Brad Schneider (D-Ill.) argued that Trump was trying to make Americans' economic anxieties disappear by telling them not to believe their own bank balances.

"The president is trying to gaslight Americans into believing that everything is fine," he observed. "The reality is millions of Americans are worried about their checking accounts and whether they can put food on the table, afford healthcare, and pay their bills."

Rep. Sylvia Garcia (D-Texas) said that Trump's dismissal of voters' affordability worries are "easy to say when you are a billionaire who has never had to choose between groceries and the light bill."

"Working families in Texas know the real scam is his tariffs, his higher premiums, and his complete failure to offer any plan to address the housing crisis or actually lower prices," Garcia added.

Keep ReadingShow Less

GOP Spending Law Gives Corporations $16 Billion in Retroactive Tax Breaks: Analysis

“You cannot change what a company did in the past, so that half-year of retroactive effect of the provision is just a windfall to companies," said one critic.

Dec 02, 2025

Corporations are likely to claim $16 in fresh tax breaks on expenditures made before the passage of the budget legislation signed earlier this year by US President Donald Trump, according to an analysis by a nonpartisan congressional committee released Tuesday.

The analysis by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT)—a panel composed of five members each from the Senate Finance Committee and House Ways and Means Committee—came in response to a September query from Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) regarding the One Big Beautiful Bill Act's (OBBBA) extension of full bonus depreciation, a tax-savings tool allowing businesses to automatically deduct costs of qualifying assets.

As Warren explained in her letter, full bonus depreciation enables corporations "to immediately deduct some or all of the cost of new business investments, such as the purchase of manufacturing equipment, software, and furniture, rather than deducting those costs over the estimated lifetime of those assets."

"This policy was first implemented in 2010 as an intended temporary economic stimulus in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and Congress allowed it to expire the following year," Warren noted.

"However, President Trump’s 2017 tax law reinstated 100% bonus depreciation from 2018 through 2022 in what amounted to a massive corporate giveaway," the senator continued, highlighting nearly $67 billion in tax savings for more than two dozen corporations including Google, Facebook, UPS, and Target.

"And after extensive lobbying from billionaire-funded right-wing lobbying groups, the OBBBA reinstated 100% bonus depreciation permanently to the tune of hundreds of billions of more dollars over the next decade," Warren added.

Applying retroactively to capital expenditures since January 19, corporate tax deductions under the OBBBA's reinstatement of the full bonus depreciation will cost $16 billion in lost federal revenue, according to the JCT's analysis. The tool has been hailed as game-changer for Bitcoin miners, who can write off 100% of hardware costs in the year of purchase.

The OBBBA provision allows firms to use the deduction to write off certain qualifying business-related properties, such as corporate jets. Meanwhile, millions of lower-income US households are suffering from the law's unprecedented cuts to vital social programs including Medicaid and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

While proponents of the full bonus depreciation argue that large corporations benefit most from the tool because they make up the lion's share of investments, critics point out that such breaks are generally poor investment incentives because they are applied after companies have already made their spending decisions.

“Thanks to Donald Trump and Republicans’ Big Beautiful Bill, giant corporations will win big while American families see their costs skyrocket," Warren said Tuesday in response to the JCT analysis. "Next year, the federal government will spend over five times more on these tax handouts for billionaire corporations than it spends each year on childcare."

"Time and time again, Donald Trump and Republicans have made clear that they stand with billionaires and billionaire corporations—not American families," she added.

Numerous corporations taking advantage of the full bonus depreciation have paid effective federal corporate tax rates far below the statutory 21%, according to a 2023 analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

One tax expert called the deduction "a cheat code to saving millions in taxes," as thousands of companies have dodged paying their fair share by effectively reducing their income to zero, or even making it negative.

As Warren noted Tuesday, "over 80% of the 100% bonus depreciation claimed by corporations from 2018-22 went to companies with over $1 billion in yearly income," while "99% of bonus depreciation benefits went to corporations making over $1 million annually."

ITEP federal policy director Steve Wamhoff told the Washington Post Tuesday that “it is quite obvious that if an incentive is retroactive, it is not actually an effective incentive."

“You cannot change what a company did in the past, so that half-year of retroactive effect of the provision is just a windfall to companies," Wamhoff added. "That part is just ridiculous.”

Keep ReadingShow Less

Most Popular