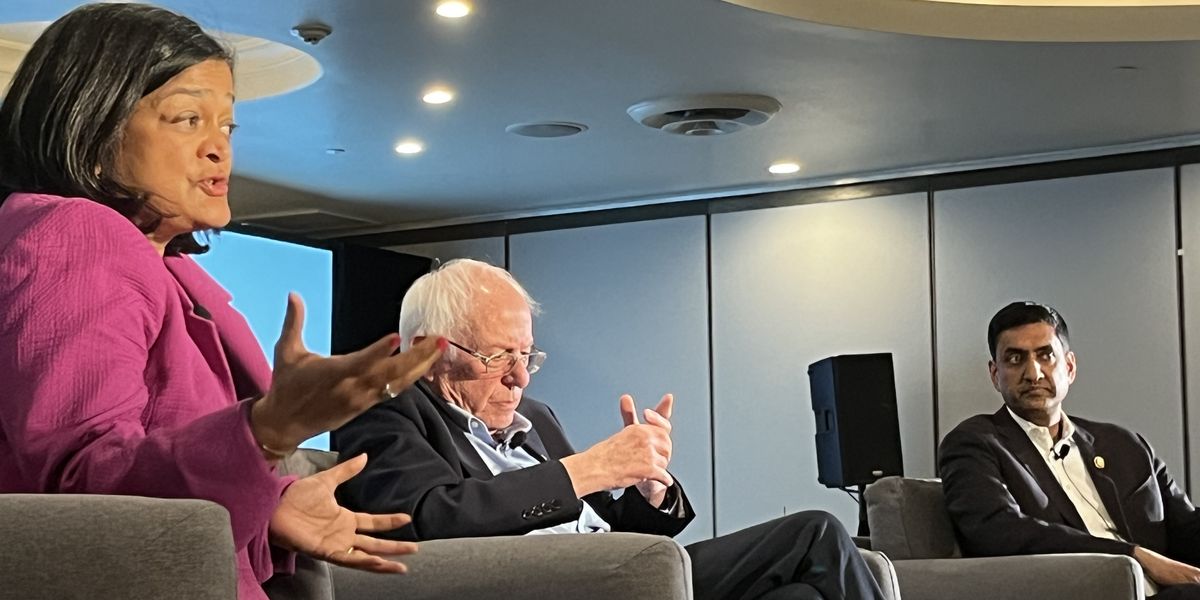

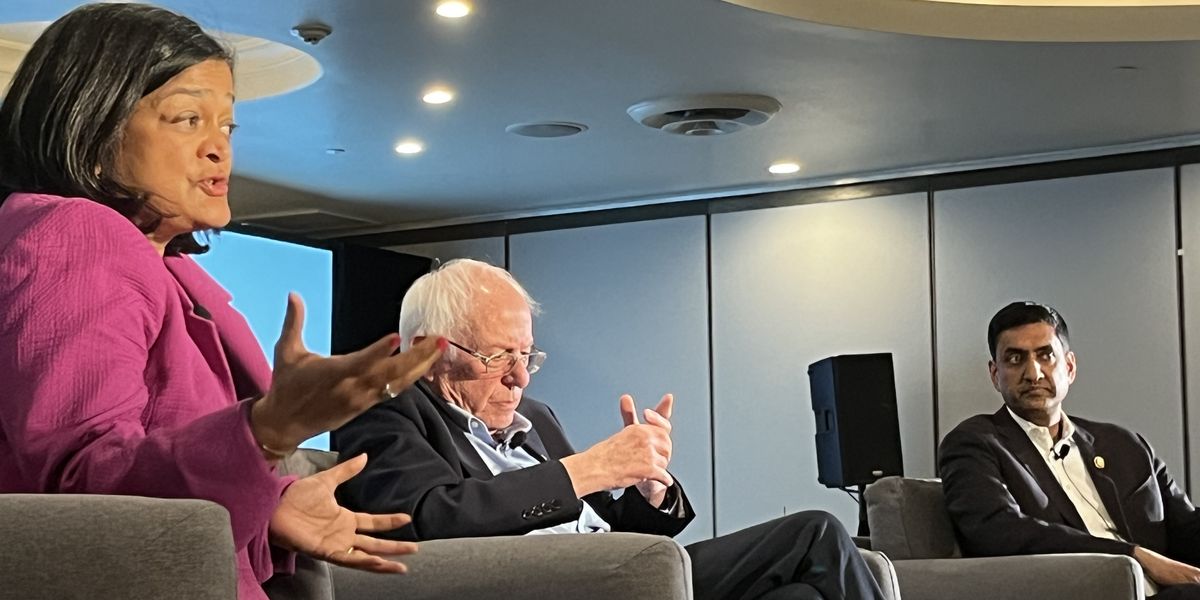

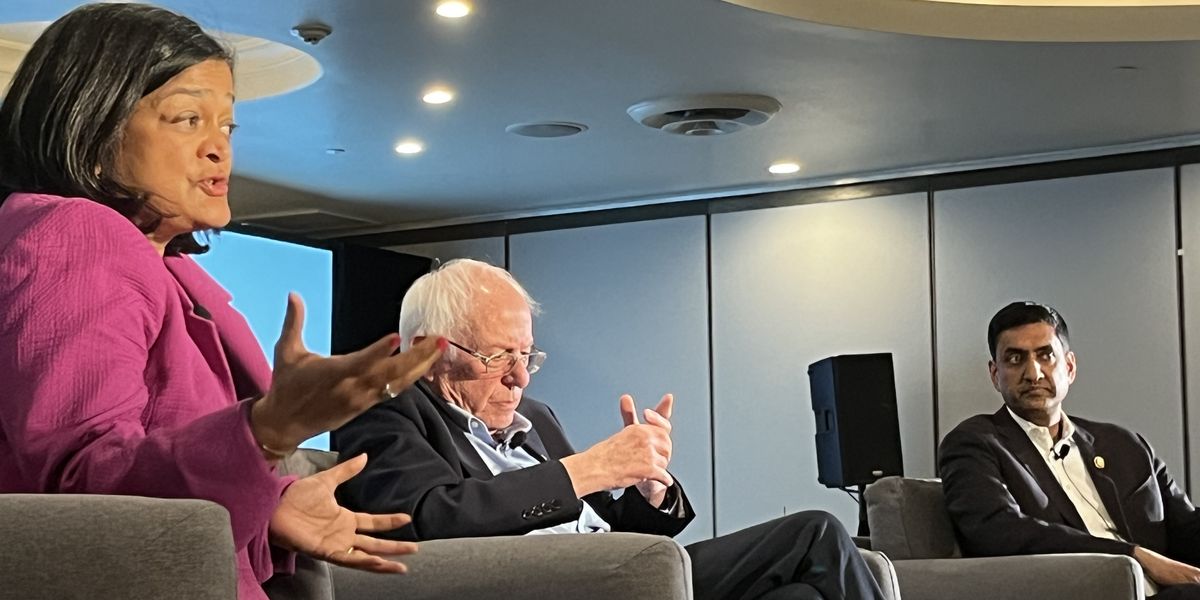

Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) speak during a panel discussion at the Sanders Institute Gathering that was held in Los Angeles, California on April 4, 2024.

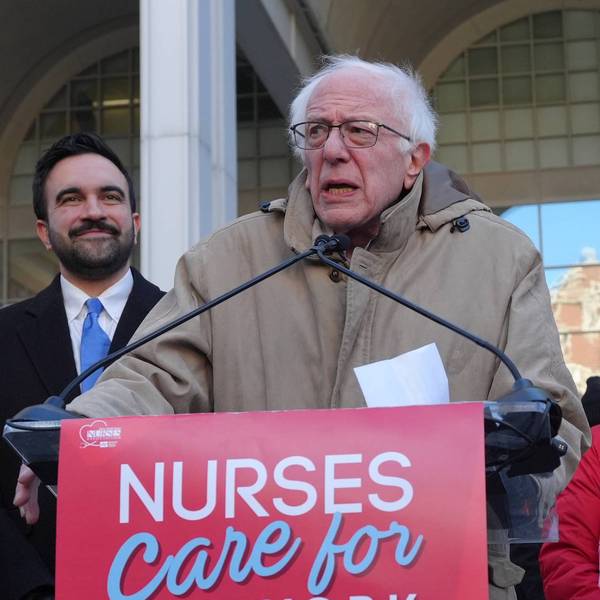

Jayapal, Sanders, and Khanna Say US Housing Crisis Must Be 'At the Top of Our Agenda'

"We really need a revolution in housing and how we deal with housing," said Sen. Bernie Sanders at a gathering on the issue.

Rent is so high in the United States that half of the nation's tenants can't afford their monthly payments. Last year, more Americans than ever experienced homelessness after the temporary pandemic safety net collapsed. Mortgage rates and through-the-roof prices have left younger generations increasingly hopeless about owning a home.

Those and other alarming facts constitute what's broadly known as the U.S. housing crisis, which a group of leading progressive lawmakers is working to elevate to the top of the Democratic Party's list of priorities ahead of the critical 2024 elections and beyond.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) made their case for a bold affordable housing push during a gathering last week in Los Angeles, California, the epicenter of the crisis. The trio of lawmakers and other participants touted a wide range of potential policy solutions during the three-day event, from national rent control to social housing to a Green New Deal for public housing.

"Housing has not been at the level it should be on the progressive agenda," Sanders said during a panel discussion with Jayapal and Khanna at the Los Angeles gathering, which was organized by the Sanders Institute—a think tank co-founded by the Vermont senator's wife, Jane O'Meara Sanders, and their son, executive director Dave Driscoll.

"This is the richest country on Earth. We're not a poor country," the senator continued. "Can we build affordable housing that we need? Can we protect? And the answer is of course we can. But it will require a massive grassroots effort to transform our political system to do that."

The other two panelists agreed, stressing that housing intersects with every aspect of life and should be a human right, not a commodity.

"How do you apply for a job if you don't have an address? How do you get your health insurance if you don't have a stable place? How do you deal with kids if you're houseless?" asked Jayapal, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC). "I think the good news is housing is at the top of our agenda now."

"Pramila is right," said Khanna, "that housing has become front and center."

In November 2021, in the midst of a deadly pandemic that left tens of millions of Americans at imminent risk of eviction, the U.S. House passed legislation that would have made the single largest investment in affordable housing in the nation's history—over $170 billion.

That legislation, known as the Build Back Better Act, died in the U.S. Senate, felled by the unanimous opposition of the chamber's Republicans and two right-wing Democrats—Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, who has since left the party to become an Independent.

The ire for Manchin and Sinema was palpable at the gathering; "two sellout Democrats" was how Sanders described the pair.

But the framework offered by the ill-fated Build Back Better package—which included tens of billions of dollars in funds for rental assistance and much-needed public housing renovations—remains a guidepost for progressives, who pushed housing to the forefront of negotiations over the bill.

"We laid the groundwork for this investment. We made the arguments for why this has to be a top priority," Jayapal said in a speech at the event. "The rent is too damn high. And that is true everywhere across the country."

The daunting situation facing tenants, prospective homeowners, and unhoused people appears even more stark when contrasted with the exploding fortunes of private equity behemoths and billionaire investors fueling—and benefiting from—soaring housing costs.

In recent years, private equity firms notorious for gutting companies and making off with a quick profit have been on a buying spree in the American housing sector, snatching up apartment buildings and single-family rental homes—sometimes with no intention of even housing tenants.

The reach of corporate landlords extends from student apartments to senior housing, from older buildings to newer luxury high-rises. One recent analysis estimates institutional investors could control as much as 40% of all single-family homes in the U.S. by decade's end.

Growing corporate ownership of the nation's housing stock has been disastrous for tenants already squeezed by other elevated living costs. The experiences of tenants across the U.S. and empirical research have shown that private-equity landlords are more likely to jack up rent (sometimes with the help of profit-maximizing algorithms), skimp on basic maintenance, and aggressively pursue evictions.

A 2022 report authored by city officials in Berkeley, California expressed alarm at the "nationwide trend where large institutional investors have since the beginning of the pandemic purchased an enormous number of homes; over 75% of these offers are in all cash, and many without any inspections, pricing prospective homeowners out of the real estate market."

That trend has drawn scrutiny from local and national lawmakers, including attendees of the Sanders Institute gathering in Los Angeles.

Khanna, the lead sponsor of the Stop Wall Street Landlords Act, told Common Dreams on the sidelines of the gathering that preventing large institutional investors from seizing an ever-growing share of the U.S. housing market is an important part of tackling the broader affordability crisis—but isn't sufficient on its own.

"I would say that the defining theme of this conference is that there needs to be some regulation on rent, and then in addition, there needs to be an increase of housing supply and a prevention of Wall Street from buying up single-family homes."

Sanders echoed that message in a separate interview with Common Dreams.

"We really need a revolution in housing and how we deal with housing," said Sanders, calling for a comprehensive approach that "deals with tenants' rights, deals with taking on the corporate interests, deals with building massive amounts of affordable housing, deals with public housing."

"It's got to be placed way up in the agenda," Sanders added.

There's not a single state in the U.S. that has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which estimates that the nation's shortage of affordable housing has grown to roughly 7.3 million units.

A recent Harvard study found that more than 12 million Americans are paying more than 50% of their income on housing.

The dearth of affordable housing nationwide has fueled state and local efforts to boost supply and rein in out-of-control rent. An initiative on the November ballot in California—which has the largest unhoused population in the country—aims to repeal a real estate industry-backed state law that limits the power of local governments to implement rent control measures.

Such rent control preemption laws exist in at least 30 states, underscoring the need for federal action.

"We really need the federal government's help here," Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco who led the largest study of U.S. homelessness in decades, said at the gathering.

The study, which examined homelessness in California, concluded that "for most of the participants, the cost of housing had simply become unsustainable."

In the face of sky-high housing costs across the country, lawmakers and advocates convened by the Sanders Institute made the case for pursuing rent control measures at the national level. Polling indicates that would be popular: A

survey conducted by Data for Progress and YouGov found that 56% of U.S. voters would support "a policy to cap rent increases to 5% a year."

Speaking on the event's opening night, Khanna rejected the neoliberal economic orthodoxy that says rent control—like other price controls—would limit supply, worsening the nation's shortage of affordable housing.

Khanna pointed to studies out of New Jersey and elsewhere showing that local rent control measures did not, in fact, negatively affect housing supply.

"It reminds me of the arguments they used to give about the minimum wage," said Khanna, pointing to the debunked notion that minimum wage hikes harm employment. "We need to argue very clearly that rent regulation—making sure that rent doesn't go too high, making sure that it doesn't exceed inflation—is about creating balance for renters in the market and not being exploited by landlords in a time of scarcity. At the same time, we should build more housing. These two aren't mutually exclusive."

Experts agree. Last year, as Common Dreams reported at the time, a group of economists including Mark Paul of Rutgers University, James K. Galbraith of the University of Texas at Austin, and Isabella Weber of the University of Massachusetts Amherst signed a letter urging the Biden administration to mandate rent caps and other tenant protections as conditions for federally backed mortgages, which support nearly half of the country's rental units.

The economists' push was part of a broader tenant-led rent control campaign backed by

climate researchers, local elected officials, and others.

In an op-ed for The American Prospect last year, Paul argued that "to truly transform the housing sector, the United States will need to embrace complementary policies to increase the number of affordable and market-rate housing units, encourage more construction and density through changes to zoning laws, and build millions of units of social housing—high-quality public housing for people across the income spectrum."

"It's a tall order," he wrote. "But embracing rent control is a commonsense place to start."

Khanna, who served as national co-chair of Sanders' 2020 presidential campaign, told Common Dreams that he wants President Joe Biden to embrace rent control as a plank of his 2024 bid, as the Vermont senator did four years ago.

"I think the president should endorse caps on rent," Khanna said. "I think that would be one of the ways to win back a lot of younger voters, a lot of progressive voters who feel that they're having a hard time making ends meet and they're saddled with student debt. They're burdened with high rent. They often have high credit card payments because of the interest rates and they're struggling in an economy that isn't working for them."

Last week, the Biden administration announced that it would limit rent increases at properties funded by the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit—a limited move that affordable housing campaigners welcomed as a step in the right direction.

“The rent is still too damn high, but this cap will provide stability to more than a million tenants," Tara Raghuveer, the director of the National Tenant Union Federation, said in response.

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable." —Sen. Bernie Sanders

In recent years, progressives in Congress have introduced numerous bills aimed at curbing runaway housing costs, boosting supply, bolstering tenants' rights, and ensuring the nation's housing stock is climate-resilient.

The Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, spearheaded by Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), would repeal the Faircloth Amendment—which artificially limits the construction of new public housing—and invest over $230 billion into making the country's public housing stock energy-efficient and zero-carbon.

Other legislation includes Rep. Cori Bush's (D-Mo.) Unhoused Bill of Rights, Jayapal's Housing Is a Human Right Act, Rep. Delia Ramirez's (D-Ill.) Tenants' Right to Organize Act, and Rep. Maxwell Frost's (D-Fla.) End Junk Fees for Renters Act.

Some of those bills make up part of the first-of-its-kind Renters Agenda unveiled last month by the congressional Renters Caucus, which was founded last year by Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Calif.), a Los Angeles representative who also spoke at the Sanders Institute gathering.

"Our goal is to make sure that the Renters Agenda is at the top of the Democratic Party agenda," Gomez said. "We have to tackle this problem if we want a healthy economy and we want our families to thrive."

But such legislation stands no chance of passing without major shifts in the composition of Congress and a president committed to ambitious solutions to the housing crisis.

During his State of the Union address last month, Biden pointed to steps his administration has taken to combat algorithmic price-fixing in the housing market and urged Congress to take action to provide relief for renters and boost the nation's lagging supply of affordable housing.

In an interview with Common Dreams, Jayapal emphasized that there's a lot more the president can do through executive action—some of which is laid out in the CPC's executive action agenda. She also argued that Biden should put housing costs at the forefront of his campaign against presumptive GOP nominee Donald Trump, who repeatedly sought steep cuts to federal housing programs during his first four years in office.

"We don't suffer from scarcity in this country, we suffer from greed," Jayapal said. "We have enough money to house people, and to create situations where people aren't going to fear for what tomorrow's going to look like, and are able to raise a family and think about more opportunity for themselves in the future. So I think housing is at the center of that."

Sanders said Jayapal is "exactly right."

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable," the Vermont senator told Common Dreams. "And the idea that you're having these private equity firms, Blackstone, et cetera, gobbling more and more of these houses up is unacceptable."

That, Sanders said, "we've got to deal with."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Rent is so high in the United States that half of the nation's tenants can't afford their monthly payments. Last year, more Americans than ever experienced homelessness after the temporary pandemic safety net collapsed. Mortgage rates and through-the-roof prices have left younger generations increasingly hopeless about owning a home.

Those and other alarming facts constitute what's broadly known as the U.S. housing crisis, which a group of leading progressive lawmakers is working to elevate to the top of the Democratic Party's list of priorities ahead of the critical 2024 elections and beyond.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) made their case for a bold affordable housing push during a gathering last week in Los Angeles, California, the epicenter of the crisis. The trio of lawmakers and other participants touted a wide range of potential policy solutions during the three-day event, from national rent control to social housing to a Green New Deal for public housing.

"Housing has not been at the level it should be on the progressive agenda," Sanders said during a panel discussion with Jayapal and Khanna at the Los Angeles gathering, which was organized by the Sanders Institute—a think tank co-founded by the Vermont senator's wife, Jane O'Meara Sanders, and their son, executive director Dave Driscoll.

"This is the richest country on Earth. We're not a poor country," the senator continued. "Can we build affordable housing that we need? Can we protect? And the answer is of course we can. But it will require a massive grassroots effort to transform our political system to do that."

The other two panelists agreed, stressing that housing intersects with every aspect of life and should be a human right, not a commodity.

"How do you apply for a job if you don't have an address? How do you get your health insurance if you don't have a stable place? How do you deal with kids if you're houseless?" asked Jayapal, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC). "I think the good news is housing is at the top of our agenda now."

"Pramila is right," said Khanna, "that housing has become front and center."

In November 2021, in the midst of a deadly pandemic that left tens of millions of Americans at imminent risk of eviction, the U.S. House passed legislation that would have made the single largest investment in affordable housing in the nation's history—over $170 billion.

That legislation, known as the Build Back Better Act, died in the U.S. Senate, felled by the unanimous opposition of the chamber's Republicans and two right-wing Democrats—Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, who has since left the party to become an Independent.

The ire for Manchin and Sinema was palpable at the gathering; "two sellout Democrats" was how Sanders described the pair.

But the framework offered by the ill-fated Build Back Better package—which included tens of billions of dollars in funds for rental assistance and much-needed public housing renovations—remains a guidepost for progressives, who pushed housing to the forefront of negotiations over the bill.

"We laid the groundwork for this investment. We made the arguments for why this has to be a top priority," Jayapal said in a speech at the event. "The rent is too damn high. And that is true everywhere across the country."

The daunting situation facing tenants, prospective homeowners, and unhoused people appears even more stark when contrasted with the exploding fortunes of private equity behemoths and billionaire investors fueling—and benefiting from—soaring housing costs.

In recent years, private equity firms notorious for gutting companies and making off with a quick profit have been on a buying spree in the American housing sector, snatching up apartment buildings and single-family rental homes—sometimes with no intention of even housing tenants.

The reach of corporate landlords extends from student apartments to senior housing, from older buildings to newer luxury high-rises. One recent analysis estimates institutional investors could control as much as 40% of all single-family homes in the U.S. by decade's end.

Growing corporate ownership of the nation's housing stock has been disastrous for tenants already squeezed by other elevated living costs. The experiences of tenants across the U.S. and empirical research have shown that private-equity landlords are more likely to jack up rent (sometimes with the help of profit-maximizing algorithms), skimp on basic maintenance, and aggressively pursue evictions.

A 2022 report authored by city officials in Berkeley, California expressed alarm at the "nationwide trend where large institutional investors have since the beginning of the pandemic purchased an enormous number of homes; over 75% of these offers are in all cash, and many without any inspections, pricing prospective homeowners out of the real estate market."

That trend has drawn scrutiny from local and national lawmakers, including attendees of the Sanders Institute gathering in Los Angeles.

Khanna, the lead sponsor of the Stop Wall Street Landlords Act, told Common Dreams on the sidelines of the gathering that preventing large institutional investors from seizing an ever-growing share of the U.S. housing market is an important part of tackling the broader affordability crisis—but isn't sufficient on its own.

"I would say that the defining theme of this conference is that there needs to be some regulation on rent, and then in addition, there needs to be an increase of housing supply and a prevention of Wall Street from buying up single-family homes."

Sanders echoed that message in a separate interview with Common Dreams.

"We really need a revolution in housing and how we deal with housing," said Sanders, calling for a comprehensive approach that "deals with tenants' rights, deals with taking on the corporate interests, deals with building massive amounts of affordable housing, deals with public housing."

"It's got to be placed way up in the agenda," Sanders added.

There's not a single state in the U.S. that has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which estimates that the nation's shortage of affordable housing has grown to roughly 7.3 million units.

A recent Harvard study found that more than 12 million Americans are paying more than 50% of their income on housing.

The dearth of affordable housing nationwide has fueled state and local efforts to boost supply and rein in out-of-control rent. An initiative on the November ballot in California—which has the largest unhoused population in the country—aims to repeal a real estate industry-backed state law that limits the power of local governments to implement rent control measures.

Such rent control preemption laws exist in at least 30 states, underscoring the need for federal action.

"We really need the federal government's help here," Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco who led the largest study of U.S. homelessness in decades, said at the gathering.

The study, which examined homelessness in California, concluded that "for most of the participants, the cost of housing had simply become unsustainable."

In the face of sky-high housing costs across the country, lawmakers and advocates convened by the Sanders Institute made the case for pursuing rent control measures at the national level. Polling indicates that would be popular: A

survey conducted by Data for Progress and YouGov found that 56% of U.S. voters would support "a policy to cap rent increases to 5% a year."

Speaking on the event's opening night, Khanna rejected the neoliberal economic orthodoxy that says rent control—like other price controls—would limit supply, worsening the nation's shortage of affordable housing.

Khanna pointed to studies out of New Jersey and elsewhere showing that local rent control measures did not, in fact, negatively affect housing supply.

"It reminds me of the arguments they used to give about the minimum wage," said Khanna, pointing to the debunked notion that minimum wage hikes harm employment. "We need to argue very clearly that rent regulation—making sure that rent doesn't go too high, making sure that it doesn't exceed inflation—is about creating balance for renters in the market and not being exploited by landlords in a time of scarcity. At the same time, we should build more housing. These two aren't mutually exclusive."

Experts agree. Last year, as Common Dreams reported at the time, a group of economists including Mark Paul of Rutgers University, James K. Galbraith of the University of Texas at Austin, and Isabella Weber of the University of Massachusetts Amherst signed a letter urging the Biden administration to mandate rent caps and other tenant protections as conditions for federally backed mortgages, which support nearly half of the country's rental units.

The economists' push was part of a broader tenant-led rent control campaign backed by

climate researchers, local elected officials, and others.

In an op-ed for The American Prospect last year, Paul argued that "to truly transform the housing sector, the United States will need to embrace complementary policies to increase the number of affordable and market-rate housing units, encourage more construction and density through changes to zoning laws, and build millions of units of social housing—high-quality public housing for people across the income spectrum."

"It's a tall order," he wrote. "But embracing rent control is a commonsense place to start."

Khanna, who served as national co-chair of Sanders' 2020 presidential campaign, told Common Dreams that he wants President Joe Biden to embrace rent control as a plank of his 2024 bid, as the Vermont senator did four years ago.

"I think the president should endorse caps on rent," Khanna said. "I think that would be one of the ways to win back a lot of younger voters, a lot of progressive voters who feel that they're having a hard time making ends meet and they're saddled with student debt. They're burdened with high rent. They often have high credit card payments because of the interest rates and they're struggling in an economy that isn't working for them."

Last week, the Biden administration announced that it would limit rent increases at properties funded by the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit—a limited move that affordable housing campaigners welcomed as a step in the right direction.

“The rent is still too damn high, but this cap will provide stability to more than a million tenants," Tara Raghuveer, the director of the National Tenant Union Federation, said in response.

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable." —Sen. Bernie Sanders

In recent years, progressives in Congress have introduced numerous bills aimed at curbing runaway housing costs, boosting supply, bolstering tenants' rights, and ensuring the nation's housing stock is climate-resilient.

The Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, spearheaded by Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), would repeal the Faircloth Amendment—which artificially limits the construction of new public housing—and invest over $230 billion into making the country's public housing stock energy-efficient and zero-carbon.

Other legislation includes Rep. Cori Bush's (D-Mo.) Unhoused Bill of Rights, Jayapal's Housing Is a Human Right Act, Rep. Delia Ramirez's (D-Ill.) Tenants' Right to Organize Act, and Rep. Maxwell Frost's (D-Fla.) End Junk Fees for Renters Act.

Some of those bills make up part of the first-of-its-kind Renters Agenda unveiled last month by the congressional Renters Caucus, which was founded last year by Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Calif.), a Los Angeles representative who also spoke at the Sanders Institute gathering.

"Our goal is to make sure that the Renters Agenda is at the top of the Democratic Party agenda," Gomez said. "We have to tackle this problem if we want a healthy economy and we want our families to thrive."

But such legislation stands no chance of passing without major shifts in the composition of Congress and a president committed to ambitious solutions to the housing crisis.

During his State of the Union address last month, Biden pointed to steps his administration has taken to combat algorithmic price-fixing in the housing market and urged Congress to take action to provide relief for renters and boost the nation's lagging supply of affordable housing.

In an interview with Common Dreams, Jayapal emphasized that there's a lot more the president can do through executive action—some of which is laid out in the CPC's executive action agenda. She also argued that Biden should put housing costs at the forefront of his campaign against presumptive GOP nominee Donald Trump, who repeatedly sought steep cuts to federal housing programs during his first four years in office.

"We don't suffer from scarcity in this country, we suffer from greed," Jayapal said. "We have enough money to house people, and to create situations where people aren't going to fear for what tomorrow's going to look like, and are able to raise a family and think about more opportunity for themselves in the future. So I think housing is at the center of that."

Sanders said Jayapal is "exactly right."

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable," the Vermont senator told Common Dreams. "And the idea that you're having these private equity firms, Blackstone, et cetera, gobbling more and more of these houses up is unacceptable."

That, Sanders said, "we've got to deal with."

- Jeff Bezos Donates $120 Million to Fight Homelessness, Then Invests $500 Million to Make It Worse ›

- Coronavirus Rent Freezes Are Ending--and A Wave of Evictions Will Sweep America ›

- 'Unacceptable': US Homelessness Hits Record High ›

- The US Housing Crisis Is 4 Decades in the Making ›

- As Housing Crisis Deepens, Corporate Landlords Applaud 'Weak' Biden Renter Protections ›

- A Lack of Supply Isn’t Causing Our Housing Crisis ›

- Opinion | Biden Rent Increase Cap Shows the Tenant Union Movement Can Win Nationally | Common Dreams ›

- Congressional Progressives Unveil 'Bold' Agenda for Second Biden Term | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | US Affordable Housing Policy Works for Wall Street and Rich Developers, Not Renters | Common Dreams ›

- A 'Focus on Solidarity' and Progressive Solutions at Latest Sanders Institute Gathering | Common Dreams ›

- Analysis Shows Embracing Bold Renter Protections Can Help Democrats Win in 2024 | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Inside San Francisco's Election Season Crackdown on Homeless People | Common Dreams ›

- 50+ Groups Demand Biden Go Further on US Housing Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The Immoral US Housing Crisis Is a Shame We Must Correct—Now | Common Dreams ›

- Ocasio-Cortez, Smith Push Bill to Create Social Housing Authority | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Why Wall Street Landlords Love a Housing Shortage | Common Dreams ›

- Billionaire Investors Are 'Supercharging' Housing Crisis: Report | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Meet the Billionaire Investors Behind the US Housing Affordability Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Congress Must Repeal Its Cap on Public Housing Now | Common Dreams ›

Rent is so high in the United States that half of the nation's tenants can't afford their monthly payments. Last year, more Americans than ever experienced homelessness after the temporary pandemic safety net collapsed. Mortgage rates and through-the-roof prices have left younger generations increasingly hopeless about owning a home.

Those and other alarming facts constitute what's broadly known as the U.S. housing crisis, which a group of leading progressive lawmakers is working to elevate to the top of the Democratic Party's list of priorities ahead of the critical 2024 elections and beyond.

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), and Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) made their case for a bold affordable housing push during a gathering last week in Los Angeles, California, the epicenter of the crisis. The trio of lawmakers and other participants touted a wide range of potential policy solutions during the three-day event, from national rent control to social housing to a Green New Deal for public housing.

"Housing has not been at the level it should be on the progressive agenda," Sanders said during a panel discussion with Jayapal and Khanna at the Los Angeles gathering, which was organized by the Sanders Institute—a think tank co-founded by the Vermont senator's wife, Jane O'Meara Sanders, and their son, executive director Dave Driscoll.

"This is the richest country on Earth. We're not a poor country," the senator continued. "Can we build affordable housing that we need? Can we protect? And the answer is of course we can. But it will require a massive grassroots effort to transform our political system to do that."

The other two panelists agreed, stressing that housing intersects with every aspect of life and should be a human right, not a commodity.

"How do you apply for a job if you don't have an address? How do you get your health insurance if you don't have a stable place? How do you deal with kids if you're houseless?" asked Jayapal, the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC). "I think the good news is housing is at the top of our agenda now."

"Pramila is right," said Khanna, "that housing has become front and center."

In November 2021, in the midst of a deadly pandemic that left tens of millions of Americans at imminent risk of eviction, the U.S. House passed legislation that would have made the single largest investment in affordable housing in the nation's history—over $170 billion.

That legislation, known as the Build Back Better Act, died in the U.S. Senate, felled by the unanimous opposition of the chamber's Republicans and two right-wing Democrats—Sens. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, who has since left the party to become an Independent.

The ire for Manchin and Sinema was palpable at the gathering; "two sellout Democrats" was how Sanders described the pair.

But the framework offered by the ill-fated Build Back Better package—which included tens of billions of dollars in funds for rental assistance and much-needed public housing renovations—remains a guidepost for progressives, who pushed housing to the forefront of negotiations over the bill.

"We laid the groundwork for this investment. We made the arguments for why this has to be a top priority," Jayapal said in a speech at the event. "The rent is too damn high. And that is true everywhere across the country."

The daunting situation facing tenants, prospective homeowners, and unhoused people appears even more stark when contrasted with the exploding fortunes of private equity behemoths and billionaire investors fueling—and benefiting from—soaring housing costs.

In recent years, private equity firms notorious for gutting companies and making off with a quick profit have been on a buying spree in the American housing sector, snatching up apartment buildings and single-family rental homes—sometimes with no intention of even housing tenants.

The reach of corporate landlords extends from student apartments to senior housing, from older buildings to newer luxury high-rises. One recent analysis estimates institutional investors could control as much as 40% of all single-family homes in the U.S. by decade's end.

Growing corporate ownership of the nation's housing stock has been disastrous for tenants already squeezed by other elevated living costs. The experiences of tenants across the U.S. and empirical research have shown that private-equity landlords are more likely to jack up rent (sometimes with the help of profit-maximizing algorithms), skimp on basic maintenance, and aggressively pursue evictions.

A 2022 report authored by city officials in Berkeley, California expressed alarm at the "nationwide trend where large institutional investors have since the beginning of the pandemic purchased an enormous number of homes; over 75% of these offers are in all cash, and many without any inspections, pricing prospective homeowners out of the real estate market."

That trend has drawn scrutiny from local and national lawmakers, including attendees of the Sanders Institute gathering in Los Angeles.

Khanna, the lead sponsor of the Stop Wall Street Landlords Act, told Common Dreams on the sidelines of the gathering that preventing large institutional investors from seizing an ever-growing share of the U.S. housing market is an important part of tackling the broader affordability crisis—but isn't sufficient on its own.

"I would say that the defining theme of this conference is that there needs to be some regulation on rent, and then in addition, there needs to be an increase of housing supply and a prevention of Wall Street from buying up single-family homes."

Sanders echoed that message in a separate interview with Common Dreams.

"We really need a revolution in housing and how we deal with housing," said Sanders, calling for a comprehensive approach that "deals with tenants' rights, deals with taking on the corporate interests, deals with building massive amounts of affordable housing, deals with public housing."

"It's got to be placed way up in the agenda," Sanders added.

There's not a single state in the U.S. that has an adequate supply of affordable rental housing for the lowest-income renters, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, which estimates that the nation's shortage of affordable housing has grown to roughly 7.3 million units.

A recent Harvard study found that more than 12 million Americans are paying more than 50% of their income on housing.

The dearth of affordable housing nationwide has fueled state and local efforts to boost supply and rein in out-of-control rent. An initiative on the November ballot in California—which has the largest unhoused population in the country—aims to repeal a real estate industry-backed state law that limits the power of local governments to implement rent control measures.

Such rent control preemption laws exist in at least 30 states, underscoring the need for federal action.

"We really need the federal government's help here," Margot Kushel, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco who led the largest study of U.S. homelessness in decades, said at the gathering.

The study, which examined homelessness in California, concluded that "for most of the participants, the cost of housing had simply become unsustainable."

In the face of sky-high housing costs across the country, lawmakers and advocates convened by the Sanders Institute made the case for pursuing rent control measures at the national level. Polling indicates that would be popular: A

survey conducted by Data for Progress and YouGov found that 56% of U.S. voters would support "a policy to cap rent increases to 5% a year."

Speaking on the event's opening night, Khanna rejected the neoliberal economic orthodoxy that says rent control—like other price controls—would limit supply, worsening the nation's shortage of affordable housing.

Khanna pointed to studies out of New Jersey and elsewhere showing that local rent control measures did not, in fact, negatively affect housing supply.

"It reminds me of the arguments they used to give about the minimum wage," said Khanna, pointing to the debunked notion that minimum wage hikes harm employment. "We need to argue very clearly that rent regulation—making sure that rent doesn't go too high, making sure that it doesn't exceed inflation—is about creating balance for renters in the market and not being exploited by landlords in a time of scarcity. At the same time, we should build more housing. These two aren't mutually exclusive."

Experts agree. Last year, as Common Dreams reported at the time, a group of economists including Mark Paul of Rutgers University, James K. Galbraith of the University of Texas at Austin, and Isabella Weber of the University of Massachusetts Amherst signed a letter urging the Biden administration to mandate rent caps and other tenant protections as conditions for federally backed mortgages, which support nearly half of the country's rental units.

The economists' push was part of a broader tenant-led rent control campaign backed by

climate researchers, local elected officials, and others.

In an op-ed for The American Prospect last year, Paul argued that "to truly transform the housing sector, the United States will need to embrace complementary policies to increase the number of affordable and market-rate housing units, encourage more construction and density through changes to zoning laws, and build millions of units of social housing—high-quality public housing for people across the income spectrum."

"It's a tall order," he wrote. "But embracing rent control is a commonsense place to start."

Khanna, who served as national co-chair of Sanders' 2020 presidential campaign, told Common Dreams that he wants President Joe Biden to embrace rent control as a plank of his 2024 bid, as the Vermont senator did four years ago.

"I think the president should endorse caps on rent," Khanna said. "I think that would be one of the ways to win back a lot of younger voters, a lot of progressive voters who feel that they're having a hard time making ends meet and they're saddled with student debt. They're burdened with high rent. They often have high credit card payments because of the interest rates and they're struggling in an economy that isn't working for them."

Last week, the Biden administration announced that it would limit rent increases at properties funded by the federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credit—a limited move that affordable housing campaigners welcomed as a step in the right direction.

“The rent is still too damn high, but this cap will provide stability to more than a million tenants," Tara Raghuveer, the director of the National Tenant Union Federation, said in response.

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable." —Sen. Bernie Sanders

In recent years, progressives in Congress have introduced numerous bills aimed at curbing runaway housing costs, boosting supply, bolstering tenants' rights, and ensuring the nation's housing stock is climate-resilient.

The Green New Deal for Public Housing Act, spearheaded by Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), would repeal the Faircloth Amendment—which artificially limits the construction of new public housing—and invest over $230 billion into making the country's public housing stock energy-efficient and zero-carbon.

Other legislation includes Rep. Cori Bush's (D-Mo.) Unhoused Bill of Rights, Jayapal's Housing Is a Human Right Act, Rep. Delia Ramirez's (D-Ill.) Tenants' Right to Organize Act, and Rep. Maxwell Frost's (D-Fla.) End Junk Fees for Renters Act.

Some of those bills make up part of the first-of-its-kind Renters Agenda unveiled last month by the congressional Renters Caucus, which was founded last year by Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D-Calif.), a Los Angeles representative who also spoke at the Sanders Institute gathering.

"Our goal is to make sure that the Renters Agenda is at the top of the Democratic Party agenda," Gomez said. "We have to tackle this problem if we want a healthy economy and we want our families to thrive."

But such legislation stands no chance of passing without major shifts in the composition of Congress and a president committed to ambitious solutions to the housing crisis.

During his State of the Union address last month, Biden pointed to steps his administration has taken to combat algorithmic price-fixing in the housing market and urged Congress to take action to provide relief for renters and boost the nation's lagging supply of affordable housing.

In an interview with Common Dreams, Jayapal emphasized that there's a lot more the president can do through executive action—some of which is laid out in the CPC's executive action agenda. She also argued that Biden should put housing costs at the forefront of his campaign against presumptive GOP nominee Donald Trump, who repeatedly sought steep cuts to federal housing programs during his first four years in office.

"We don't suffer from scarcity in this country, we suffer from greed," Jayapal said. "We have enough money to house people, and to create situations where people aren't going to fear for what tomorrow's going to look like, and are able to raise a family and think about more opportunity for themselves in the future. So I think housing is at the center of that."

Sanders said Jayapal is "exactly right."

"The idea that we have millions of families in America paying 50% or more of their income on housing is unconscionable," the Vermont senator told Common Dreams. "And the idea that you're having these private equity firms, Blackstone, et cetera, gobbling more and more of these houses up is unacceptable."

That, Sanders said, "we've got to deal with."

- Jeff Bezos Donates $120 Million to Fight Homelessness, Then Invests $500 Million to Make It Worse ›

- Coronavirus Rent Freezes Are Ending--and A Wave of Evictions Will Sweep America ›

- 'Unacceptable': US Homelessness Hits Record High ›

- The US Housing Crisis Is 4 Decades in the Making ›

- As Housing Crisis Deepens, Corporate Landlords Applaud 'Weak' Biden Renter Protections ›

- A Lack of Supply Isn’t Causing Our Housing Crisis ›

- Opinion | Biden Rent Increase Cap Shows the Tenant Union Movement Can Win Nationally | Common Dreams ›

- Congressional Progressives Unveil 'Bold' Agenda for Second Biden Term | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | US Affordable Housing Policy Works for Wall Street and Rich Developers, Not Renters | Common Dreams ›

- A 'Focus on Solidarity' and Progressive Solutions at Latest Sanders Institute Gathering | Common Dreams ›

- Analysis Shows Embracing Bold Renter Protections Can Help Democrats Win in 2024 | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Inside San Francisco's Election Season Crackdown on Homeless People | Common Dreams ›

- 50+ Groups Demand Biden Go Further on US Housing Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | The Immoral US Housing Crisis Is a Shame We Must Correct—Now | Common Dreams ›

- Ocasio-Cortez, Smith Push Bill to Create Social Housing Authority | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Why Wall Street Landlords Love a Housing Shortage | Common Dreams ›

- Billionaire Investors Are 'Supercharging' Housing Crisis: Report | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Meet the Billionaire Investors Behind the US Housing Affordability Crisis | Common Dreams ›

- Opinion | Congress Must Repeal Its Cap on Public Housing Now | Common Dreams ›