SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

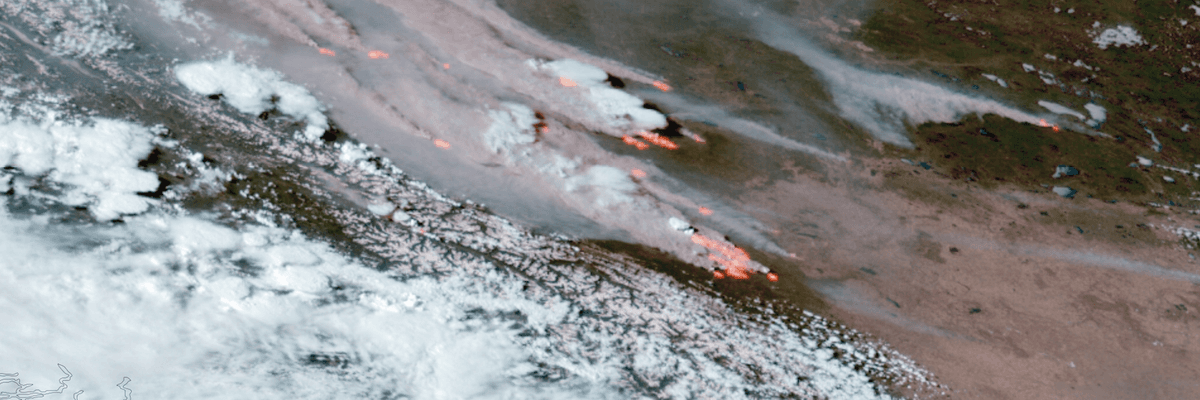

A large cluster of wildfires burns in Alberta, Canada, as seen from NOAA’s GOES-18 satellite on May 5, 2023; May 2023 was North America’s warmest May in NOAA’s 174-year climate record.

Some scientists predict that 2023 could be the warmest year on record, as a developing El Niño exacerbates the impacts of the climate crisis.

Following a May of record ocean temperatures and a June of record air temperatures, scientists are warning that 2023 could be the hottest year on record.

For a brief period in June, average global air temperatures even topped 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, the temperature goal enshrined by the Paris climate agreement.

"The world has just experienced its warmest early June on record, following a month of May that was less than 0.1°C cooler than the warmest May on record," the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Deputy Director Samantha Burgess said in a statement. "Monitoring our climate is more important than ever to determine how often and for how long global temperatures are exceeding 1.5°C. Every single fraction of a degree matters to avoid even more severe consequences of the climate crisis."

Overall, global mean surface air temperatures for early June were higher than previous C3S data for the month "by a substantial margin," the service said. Between June 7 and 11, those temperatures were above 1.5°C, peaking at 1.69°C June 9, Agence France-Presse reported.

This is not the first time that averages have poked above the 1.5°C target for a limited time. In fact, ironically, the first time was around the negotiating of the Paris agreement in December 2015.

"As it happens, a strong El Niño was close to its peak at the time, and it is now estimated that for a few days the global mean temperature was more than 1.5°C higher than the preindustrial temperature for the month," C3S said. "This was probably the first time this had occurred in the industrial era."

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record."

While there have been more incidents between 2015 and now, they were typically in the Northern Hemisphere winter and early spring. This is the first time averages have risen above 1.5°C in June.

The breach is a "stern warning sign that we are heading into very warm uncharted territory," Melissa Lazenby, a lecturer in climate change at Sussex University in the U.K., told Sky News.

It also comes amidst other concerning climate indicators. On Wednesday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the U.S. announced that average ocean surface temperatures for May reached a record high for the second month in a row. May 2023 overall was the third warmest May on record, and sea ice in Antarctica dwindled to record low levels for the month.

NOAA's findings came a week after it declared that El Niño conditions had arrived, which could exacerbate the impacts of the climate crisis to raise temperatures and fuel more extreme weather events.

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record," University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann told The Guardian. "That is likely to be true for just about every El Niño year in the future as well, as long as we continue to warm the planet with fossil fuel burning and carbon pollution."

Already this year, warm spring temperatures have had consequences, from unprecedented wildfires in Canada that smothered the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. in smoke to a fish die-off in the Gulf of Mexico.

"With climate change and global warming, it's been an interesting start to the season," NOAA climatologist Rocky Bilotta said during a press call reported by The New York Times.

University of California, Los Angeles climate scientist Daniel Swain told ABC News that the high ocean temperatures were caused by a mixture of the climate crisis, the developing El Niño, the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano eruption, and a reduction in shipping emissions that has removed cooling aerosols from the atmosphere.

If such warming persists, it could have serious consequences because warmer oceans fuel stronger tropical storms and a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture that can worsen flooding events. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) warned in May that there was a 66% chance that El Niño would work with climate change to push at least one year's average temperature past 1.5°C above preindustrial levels between 2023 and 2027.

C3S noted that the 1.5°C and 2°C temperature targets were based on averages over 20 to 30 years. However, the service added, "as the global mean temperature continues to rise and more frequently exceed the 1.5°C limit, the cumulative effects of the exceedances will become increasingly serious."

Scientists and activists said these breaches, and other recent temperature anomalies and extreme weather events, should serve as a warning to policymakers to act quickly to phase out fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

"Without stronger emission cuts, the changes we are seeing are just the start of the adverse impacts we can expect to see," Cornell University atmospheric scientist Natalie Mahowald told The Guardian. "This year and the extreme events we have seen so far should serve as a warning."

Activist Bill McKibben meanwhile said the scariest element of recent weather news was that "the world isn't reacting rationally to it."

"The rapid warming over the next couple of years is likely to be our last opportunity to really act coherently as a civilization to reduce the magnitude of this crisis, and so far we are blowing it," he wrote Thursday.

Indeed, U.N. climate talks in Bonn, Germany, which were intended to prepare the way for the COP28 climate conference in the United Arab Emirates in November and December, ended Thursday with an impasse between the E.U. and climate vulnerable countries who want faster emissions cuts and a fossil fuel phaseout, and developing countries that want more climate finance from the Global North, as AFP explained.

"The gap between the Bonn political performance and the harsh climate reality feels already absurd," Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia, told AFP. "Climate impacts stay no longer on paper. People are feeling and suffering from it now."

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres warned during a press conference Thursday that current national policies put the world on track for 2.8°C of warming by 2100.

"That spells catastrophe," Guterres said. "Yet the collective response remains pitiful."

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Following a May of record ocean temperatures and a June of record air temperatures, scientists are warning that 2023 could be the hottest year on record.

For a brief period in June, average global air temperatures even topped 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, the temperature goal enshrined by the Paris climate agreement.

"The world has just experienced its warmest early June on record, following a month of May that was less than 0.1°C cooler than the warmest May on record," the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Deputy Director Samantha Burgess said in a statement. "Monitoring our climate is more important than ever to determine how often and for how long global temperatures are exceeding 1.5°C. Every single fraction of a degree matters to avoid even more severe consequences of the climate crisis."

Overall, global mean surface air temperatures for early June were higher than previous C3S data for the month "by a substantial margin," the service said. Between June 7 and 11, those temperatures were above 1.5°C, peaking at 1.69°C June 9, Agence France-Presse reported.

This is not the first time that averages have poked above the 1.5°C target for a limited time. In fact, ironically, the first time was around the negotiating of the Paris agreement in December 2015.

"As it happens, a strong El Niño was close to its peak at the time, and it is now estimated that for a few days the global mean temperature was more than 1.5°C higher than the preindustrial temperature for the month," C3S said. "This was probably the first time this had occurred in the industrial era."

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record."

While there have been more incidents between 2015 and now, they were typically in the Northern Hemisphere winter and early spring. This is the first time averages have risen above 1.5°C in June.

The breach is a "stern warning sign that we are heading into very warm uncharted territory," Melissa Lazenby, a lecturer in climate change at Sussex University in the U.K., told Sky News.

It also comes amidst other concerning climate indicators. On Wednesday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the U.S. announced that average ocean surface temperatures for May reached a record high for the second month in a row. May 2023 overall was the third warmest May on record, and sea ice in Antarctica dwindled to record low levels for the month.

NOAA's findings came a week after it declared that El Niño conditions had arrived, which could exacerbate the impacts of the climate crisis to raise temperatures and fuel more extreme weather events.

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record," University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann told The Guardian. "That is likely to be true for just about every El Niño year in the future as well, as long as we continue to warm the planet with fossil fuel burning and carbon pollution."

Already this year, warm spring temperatures have had consequences, from unprecedented wildfires in Canada that smothered the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. in smoke to a fish die-off in the Gulf of Mexico.

"With climate change and global warming, it's been an interesting start to the season," NOAA climatologist Rocky Bilotta said during a press call reported by The New York Times.

University of California, Los Angeles climate scientist Daniel Swain told ABC News that the high ocean temperatures were caused by a mixture of the climate crisis, the developing El Niño, the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano eruption, and a reduction in shipping emissions that has removed cooling aerosols from the atmosphere.

If such warming persists, it could have serious consequences because warmer oceans fuel stronger tropical storms and a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture that can worsen flooding events. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) warned in May that there was a 66% chance that El Niño would work with climate change to push at least one year's average temperature past 1.5°C above preindustrial levels between 2023 and 2027.

C3S noted that the 1.5°C and 2°C temperature targets were based on averages over 20 to 30 years. However, the service added, "as the global mean temperature continues to rise and more frequently exceed the 1.5°C limit, the cumulative effects of the exceedances will become increasingly serious."

Scientists and activists said these breaches, and other recent temperature anomalies and extreme weather events, should serve as a warning to policymakers to act quickly to phase out fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

"Without stronger emission cuts, the changes we are seeing are just the start of the adverse impacts we can expect to see," Cornell University atmospheric scientist Natalie Mahowald told The Guardian. "This year and the extreme events we have seen so far should serve as a warning."

Activist Bill McKibben meanwhile said the scariest element of recent weather news was that "the world isn't reacting rationally to it."

"The rapid warming over the next couple of years is likely to be our last opportunity to really act coherently as a civilization to reduce the magnitude of this crisis, and so far we are blowing it," he wrote Thursday.

Indeed, U.N. climate talks in Bonn, Germany, which were intended to prepare the way for the COP28 climate conference in the United Arab Emirates in November and December, ended Thursday with an impasse between the E.U. and climate vulnerable countries who want faster emissions cuts and a fossil fuel phaseout, and developing countries that want more climate finance from the Global North, as AFP explained.

"The gap between the Bonn political performance and the harsh climate reality feels already absurd," Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia, told AFP. "Climate impacts stay no longer on paper. People are feeling and suffering from it now."

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres warned during a press conference Thursday that current national policies put the world on track for 2.8°C of warming by 2100.

"That spells catastrophe," Guterres said. "Yet the collective response remains pitiful."

Following a May of record ocean temperatures and a June of record air temperatures, scientists are warning that 2023 could be the hottest year on record.

For a brief period in June, average global air temperatures even topped 1.5°C above preindustrial levels, the temperature goal enshrined by the Paris climate agreement.

"The world has just experienced its warmest early June on record, following a month of May that was less than 0.1°C cooler than the warmest May on record," the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Deputy Director Samantha Burgess said in a statement. "Monitoring our climate is more important than ever to determine how often and for how long global temperatures are exceeding 1.5°C. Every single fraction of a degree matters to avoid even more severe consequences of the climate crisis."

Overall, global mean surface air temperatures for early June were higher than previous C3S data for the month "by a substantial margin," the service said. Between June 7 and 11, those temperatures were above 1.5°C, peaking at 1.69°C June 9, Agence France-Presse reported.

This is not the first time that averages have poked above the 1.5°C target for a limited time. In fact, ironically, the first time was around the negotiating of the Paris agreement in December 2015.

"As it happens, a strong El Niño was close to its peak at the time, and it is now estimated that for a few days the global mean temperature was more than 1.5°C higher than the preindustrial temperature for the month," C3S said. "This was probably the first time this had occurred in the industrial era."

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record."

While there have been more incidents between 2015 and now, they were typically in the Northern Hemisphere winter and early spring. This is the first time averages have risen above 1.5°C in June.

The breach is a "stern warning sign that we are heading into very warm uncharted territory," Melissa Lazenby, a lecturer in climate change at Sussex University in the U.K., told Sky News.

It also comes amidst other concerning climate indicators. On Wednesday, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the U.S. announced that average ocean surface temperatures for May reached a record high for the second month in a row. May 2023 overall was the third warmest May on record, and sea ice in Antarctica dwindled to record low levels for the month.

NOAA's findings came a week after it declared that El Niño conditions had arrived, which could exacerbate the impacts of the climate crisis to raise temperatures and fuel more extreme weather events.

"The global surface temperature anomaly is at or near record levels right now, and 2023 will almost certainly be the warmest year on record," University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann told The Guardian. "That is likely to be true for just about every El Niño year in the future as well, as long as we continue to warm the planet with fossil fuel burning and carbon pollution."

Already this year, warm spring temperatures have had consequences, from unprecedented wildfires in Canada that smothered the Eastern and Midwestern U.S. in smoke to a fish die-off in the Gulf of Mexico.

"With climate change and global warming, it's been an interesting start to the season," NOAA climatologist Rocky Bilotta said during a press call reported by The New York Times.

University of California, Los Angeles climate scientist Daniel Swain told ABC News that the high ocean temperatures were caused by a mixture of the climate crisis, the developing El Niño, the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha'apai volcano eruption, and a reduction in shipping emissions that has removed cooling aerosols from the atmosphere.

If such warming persists, it could have serious consequences because warmer oceans fuel stronger tropical storms and a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture that can worsen flooding events. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) warned in May that there was a 66% chance that El Niño would work with climate change to push at least one year's average temperature past 1.5°C above preindustrial levels between 2023 and 2027.

C3S noted that the 1.5°C and 2°C temperature targets were based on averages over 20 to 30 years. However, the service added, "as the global mean temperature continues to rise and more frequently exceed the 1.5°C limit, the cumulative effects of the exceedances will become increasingly serious."

Scientists and activists said these breaches, and other recent temperature anomalies and extreme weather events, should serve as a warning to policymakers to act quickly to phase out fossil fuels and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

"Without stronger emission cuts, the changes we are seeing are just the start of the adverse impacts we can expect to see," Cornell University atmospheric scientist Natalie Mahowald told The Guardian. "This year and the extreme events we have seen so far should serve as a warning."

Activist Bill McKibben meanwhile said the scariest element of recent weather news was that "the world isn't reacting rationally to it."

"The rapid warming over the next couple of years is likely to be our last opportunity to really act coherently as a civilization to reduce the magnitude of this crisis, and so far we are blowing it," he wrote Thursday.

Indeed, U.N. climate talks in Bonn, Germany, which were intended to prepare the way for the COP28 climate conference in the United Arab Emirates in November and December, ended Thursday with an impasse between the E.U. and climate vulnerable countries who want faster emissions cuts and a fossil fuel phaseout, and developing countries that want more climate finance from the Global North, as AFP explained.

"The gap between the Bonn political performance and the harsh climate reality feels already absurd," Li Shuo, a senior global policy adviser at Greenpeace East Asia, told AFP. "Climate impacts stay no longer on paper. People are feeling and suffering from it now."

U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres warned during a press conference Thursday that current national policies put the world on track for 2.8°C of warming by 2100.

"That spells catastrophe," Guterres said. "Yet the collective response remains pitiful."