There has always existed a fundamental tension between those who seek to amplify the voices of the oppressed and the vulnerable and those who paint a rosier picture, one that acknowledges superficial flaws but seeks, ultimately, to justify the prevailing order, economic or otherwise.

In January of 1963, Dwight Macdonald, in his famous essay reviewing Michael Harrington's groundbreaking book The Other America, cast a light on this perpetual conflict.

"For a long time now," Macdonald wrote, "almost everybody has assumed that, because of the New Deal's social legislation and -- more important -- the prosperity we have enjoyed since 1940, mass poverty no longer exists in this country."

Referring to John Kenneth Galbraith's declaration in his 1958 work The Affluent Society that poverty "can no longer be presented as a universal or massive affliction," Macdonald expressed dismay at the fact that such a "humane critic" as Galbraith could downplay (and, in some cases, overlook entirely) the tremendous suffering felt in marginalized communities -- particularly in communities of color.

But MacDonald was forgiving, noting that Galbraith's perception equaled that of many Americans at the time, including experts.

Harrington's work, in Macdonald's assessment, did much to call the public's -- and the political establishment's -- attention to the fact that "mass poverty still exists in the United States, and that it is disappearing more slowly than is commonly thought."

"In the last year," Macdonald notes, "we seem to have suddenly awakened, rubbing our eyes like Rip van Winkle, to the fact that mass poverty persists, and that it is one of our two gravest social problems. (The other is related: While only eleven per cent of our population is non-white, twenty-five per cent of our poor are.)"

Among the awakened, the story goes, was President John F. Kennedy, who was reportedly spurred into action by close readings of both Macdonald's review of The Other America and of the book itself.

A democratic socialist had caught the ear of the president -- and though he would often note that the government failed utterly to act on many of his recommendations, his work changed the national conversation.

And it corresponded with other seismic shifts in American political and economic consciousness, specifically with regard to one of our "two gravest social problems," as Macdonald had put it: The fact that black and Latino communities were disproportionately impacted by an unequal and predatory economic order.

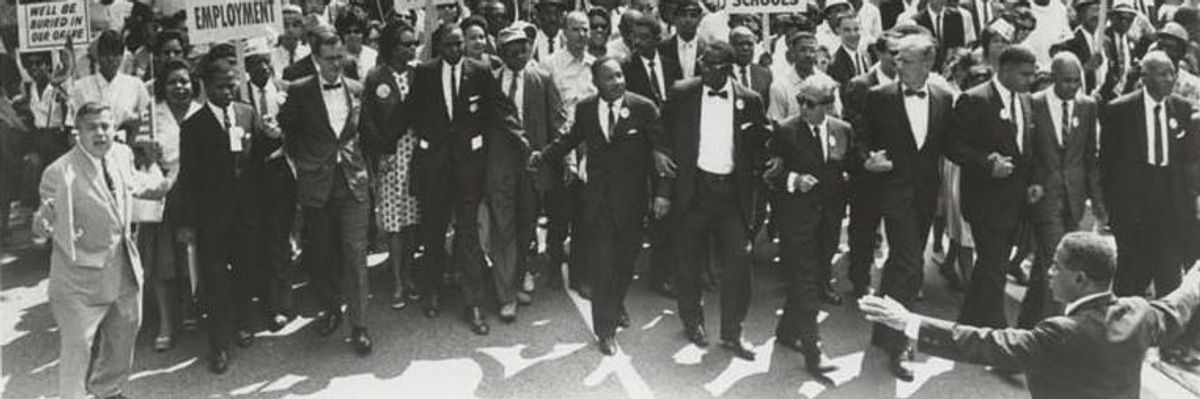

The year after The Other America was first published, the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom grabbed the attention of the nation. Organized by a "network of democratic socialists" and civil rights leaders -- including Bayard Rustin and A. Philip Randolph -- in conjunction with labor organizers, the march set forth an ambitious agenda calling for robust anti-discrimination measures, civil rights legislation, and a higher nationwide minimum wage.

Though discussions of the march often cleanse it of its radical economic message, it was there, and it was embraced by the man who would, on the same day, deliver his "I Have a Dream" speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial -- the same man who once said jokingly to Harrington that "we didn't know we were poor until we read your book."

The notion that change would eventually come from the top down -- that idealism and radicalism are tools of the foolish -- never infiltrated the minds of those who labored for decades to overcome the horrific injustices perpetuated by the American political establishment.

"These rights," A. Philip Randolph observed of the equality for which he strove, "will not be given. They must be taken."

Needless to say, this year is not 1963, but there are lessons to be learned from a period of such remarkable turmoil -- and of such remarkable progress.

A democratic socialist in the tradition of Michael Harrington -- a democratic socialist who joined Martin Luther King Jr. and 250,000 others in the march demanding racial and economic justice -- emerged as a major contender in the Democratic presidential race, defying the political class and astonishing those who scoffed at the notion of a socialist pursuing the White House.

By speaking clearly -- and in moral terms -- about the corruption of America's political system and about the conditions of the most vulnerable, Bernie Sanders brought to the fore divisions within the Democratic Party that so often lay dormant.

These were divisions understood by figures like Harrington and Rustin, who often decried both the "reactionary policies" of conservatives along with the "irresponsibility and elitism of New Politics liberals."

The party establishment Sanders confronted as he began to garner mass support is one that has has shown itself to be openly hostile to the radical change necessary to address the nation's deep economic, political, and environmental crises.

It is a party that embraces the lobbyist class and conservative billionaires willing to open their wallets in exchange for access.

"The Democrats' embrace of amoral billionaires makes it highly unlikely that the party will follow through on any meaningful attempt to reduce American economic inequality," notes Nathan Robinson. "In today's Democratic Party, predatory lenders and workplace harassers are welcome, so long as they share the goal of making Hillary Clinton the President of the United States of America."

It is a party now dedicated to the trope that "America is already great," a rhetorical flourish that provides both a shameful defense of the status quo and little comfort -- much less material relief -- to those victimized by American capitalism.

But most of the population, particularly those on the margins -- from the immigrants working in horrific conditions to the communities torn apart by austerity and neglect -- understand that, to use Eddie Glaude's phrase, "business as usual is unacceptable."

A political and economic order that delivers massive gains to those at the top while leaving everyone else to compete for a dwindling cut cannot, with any honesty, be considered "great." A system that prioritizes party unity and "pragmatic" compromise over principle, a system that places the needs of the donor class above those of working families, cannot, with any honesty, be labeled democratic.

Millions have revolted against this entrenched order. Many of them were motivated by the successes of Bernie Sanders; many were already doing the work that allowed Sanders to emerge as a viable candidate.

The Democratic Socialists of America "organized a socialist caucus" corresponding with the Democratic National Convention, during which leftists contended with the issues facing the United States and discussed how best to address them in a political context dominated by two parties, both of which are out of touch with the needs of the most vulnerable. Since Sanders entered the race, DSA has seen a significant attention boost, one that the organization's leaders hope will translate into long-term membership growth.

Also organizing at the convention was the Working Families Party, founded in 1998, whose goal is to "put leftward pressure on the Democratic Party" and to stop the "conservative shift among Democrats."

The Working Families Party has joined the Fight for $15 movement in its call for a $15 minimum wage nationwide and it has fought in solidarity with labor unions for mandated paid sick leave, equal pay for women, and universal health care.

The Green Party, facing a population that is greatly dissatisfied with both major parties, has made notable progress during this year's election cycle, and it has called attention to the moral and ideological bankruptcy of the Democratic Party while also focusing intensely on environmental degradation.

"We face unprecedented crises that call for transformational solutions, a new way forward based on democracy, justice and human rights," said Green Party presidential nominee Jill Stein at the party's convention. "And that won't come from corporate political parties funded by predatory banks, war profiteers and fossil fuel giants."

Black Lives Matter, having begun as an effort to organize against police brutality and violence and to call attention to systemic racism, has gone international, and the movement has recently released a remarkable policy platform -- endorsed and celebrated by the Democratic Socialists of America -- that includes a call for economic justice that echoes the inspiring messages of Diane Nash, Bayard Rustin, and Dr. King.

"This document is so important," notes Steven Pitts, who worked with the group on the economic portion of the platform, "because it can help to broaden the scope of the conversation and place the context of Black death and police murder within the context of institutional racism and neoliberalism."

Calls for racial justice throughout the Civil Rights Movement were always conjoined with a radical economic vision, one that decried "socialism for the rich" and called attention to the fact that poor communities lack clean water, good schools, and adequate health care.

Today, some neighborhoods in Baltimore, for instance, have a life expectancy comparable to that of North Korea, and black families were, in many areas, disproportionately affected by the 2008 financial crisis, having been targeted by predatory institutions.

By releasing such a comprehensive document, Black Lives Matter has, writes Douglas Williams, created "a banner behind which the Black working class can march and fight. It does this by seeking to address the challenges working class Black people face in their day-to-day lives under racialized capitalism."

The document also focuses specifically on union organizing, which The Week's Ryan Cooper rightly calls "the traditional foundation of left-wing politics."

Unions, Cooper notes, "were largely abandoned by the Democratic Party during the turn to neoliberalism in the 1990s. This platform goes well beyond Clinton-style liberalism; at times, it basically mainlines Bernie Sanders."

Black Lives Matter, like all effective progressive movements, understands that we cannot expect much more than tepid political change in the absence of mass democratic action from below.

In putting forward radical economic proposals that strike at the heart of the established order, the organization is challenging a political class that, for all its differences, remains almost unanimously committed to the fundamentals of a system that has produced soaring inequality and deep poverty while delivering most of its gains to the very top.

As the campaign of Hillary Clinton ponders how best to deploy its billionaire backers, leftists are organizing for a better future in a nation in which 15 percent of the population lives in poverty, according to official Census Bureau statistics. And the reality, notes Paul Buchheit, is "actually much worse."

"According to a new analysis by the McKinsey Global Institute," notes Neil Irwin, "81 percent of the United States population is in an income bracket with flat or declining income over the last decade."

Having abandoned the class politics necessary to address issues that stem from the very core of the American economic system, Democratic leaders have consistently shown that they cannot be much more than what John Dewey called "useful brakes" -- and often, they are much worse than that.

"Nothing Clinton says or intends to do if elected will fundamentally transform the circumstances of the most vulnerable in this country -- even with her concessions to the Sanders campaign," argues Eddie Glaude. "Like the majority of Democratic politicians these days, she is a corporate Democrat intent on maintaining the status quo. And I have had enough of all of them."

With their rejection of the Democratic Party's limited platform and of its commitment to a business class dedicated to maintaining the structures that produce tremendous suffering and exploitation, a diverse coalition of progressive activists is offering an inspiring way forward. We should all be listening closely.

"There is a war going on, a war that doesn't get discussed in the corporate media," Bernie Sanders said in 2007, at the Democratic Socialists of America's convention in Atlanta. "That is, a war against the middle class and working families. It's time we raise this to the level it deserves."