SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

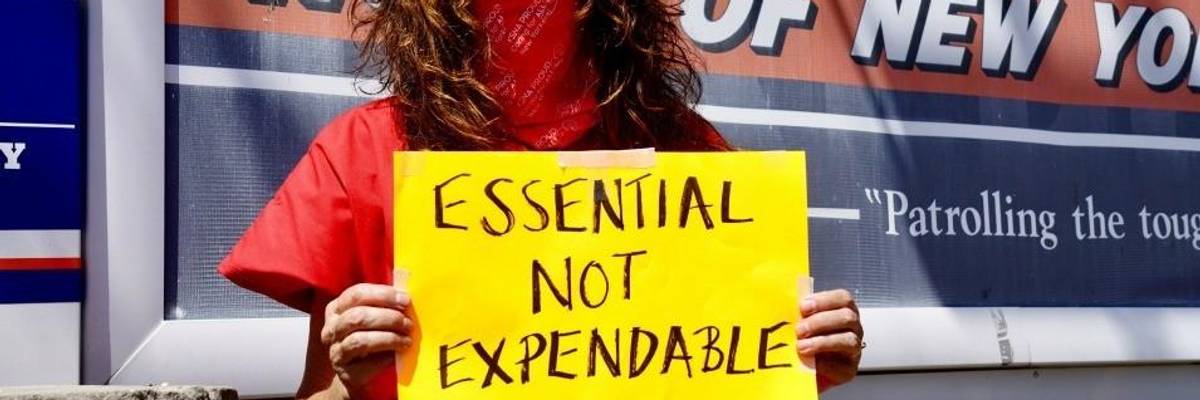

When the pandemic finally ends, there's a danger that some modified version of this new system of labor exploitation might prove too profitable for employers to abandon. (Photo: Giles Clarke/Getty Images)

In two weeks, my partner and I were supposed to leave San Francisco for Reno, Nevada, where we'd be spending the next three months focused on the 2020 presidential election. As we did in 2018, we'd be working with UNITE-HERE, the hospitality industry union, only this time on the campaign to drive Donald Trump from office.

Now, however, we're not so sure we ought to go. According to information prepared for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, Nevada is among the states in the "red zone" when it comes to both confirmed cases of, and positive tests for, Covid-19. I'm 68. My partner's five years older, with a history of pneumonia. We're both active and fit (when I'm not tripping over curbs), but our ages make us more likely, if we catch the coronavirus, to get seriously ill or even die. That gives a person pause.

Then there's the fact that Joe Biden seems to have a double-digit lead over Trump nationally and at least an eight-point lead in Nevada, according to the latest polls. If things looked closer, I would cheerfully take some serious risks to dislodge that man in the White House. But does it make sense to do so if Biden is already likely to win there? Or, to put it in coronavirus-speak, would our work be essential to dumping Trump?

Essential Work?

This minor personal conundrum got me thinking about how the pandemic has exposed certain deep and unexamined assumptions about the nature and value of work in the United States.

In the ethics classes I teach undergraduates at a college here in San Francisco, we often talk about work. Ethics is, after all, about how we ought to live our lives -- and work, paid or unpaid, constitutes a big part of most of those lives. Inevitably, the conversation comes around to compensation: How much do people deserve for different kinds of work? Students tend to measure fair compensation on two scales. How many years of training and/or dollars of tuition did a worker have to invest to become "qualified" for the job? And how important is that worker's labor to the rest of society?

Even before the coronavirus hit, students would often settle on medical doctors as belonging at the top of either scale. Physicians' work is the most important, they'd argue, because they keep us alive. "Hmm..." I'd say. "How many of you went to the doctor today?" Usually not a hand would be raised. "How many of you ate something today?" All hands would go up, as students looked around the room at one another. "Maybe," I'd suggest, "a functioning society depends more on the farmworkers who plant and harvest food than on the doctors you normally might see for a checkup once a year. Not to mention the people who process and pack what we eat."

I'd also point out that the workers who pick or process our food are not really unskilled. Their work, like a surgeon's, depends on deft, quick hand movements, honed through years of practice.

Sometimes, in these discussions, I'd propose a different metric for compensation: maybe we should reserve the highest pay for people whose jobs are both essential and dangerous. Before the pandemic, that category would not have included many healthcare workers and certainly not most doctors. Even then, however, it would have encompassed farmworkers and people laboring in meat processing plants. As we've seen, in these months it is precisely such people -- often immigrants, documented or otherwise -- who have also borne some of the worst risks of virus exposure at work.

By the end of April, when it was already clear that meatpacking plants were major sites of Covid-19 infection, the president invoked the Defense Production Act to keep them open anyway. This not only meant that workers afraid to enter them could not file for unemployment payments, but that even if the owners of such dangerous workplaces wanted to shut them down, they were forbidden to do so. By mid-June, more than 24,000 meatpackers had tested positive for the virus. And just how much do these essential and deeply endangered workers earn? According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about $28,450 a year -- better than minimum wage, that is, but hardly living high on the hog (even when that's what they're handling).

You might think that farmworkers would be more protected from the virus than meatpackers, perhaps because they work outdoors. But as the New York Times has reported: "Fruit and vegetable pickers toil close to each other in fields, ride buses shoulder-to-shoulder, and sleep in cramped apartments or trailers with other laborers or several generations of their families."

Not surprisingly, then, the coronavirus has, as the Times report puts it, "ravaged" migrant farm worker communities in Florida and is starting to do the same across the country all the way to eastern Oregon. Those workers, who risk their lives through exposure not only to a pandemic but to more ordinary dangers like herbicides and pesticides so we can eat, make even less than meatpackers: on average, under $26,000 a year.

When the president uses the Defense Production Act to ensure that food workers remain in their jobs, it reveals just how important their labor truly is to the rest of us. Similarly, as shutdown orders have kept home those who can afford to stay in, or who have no choice because they no longer have jobs to go to, the pandemic has revealed the crucial nature of the labor of a large group of workers already at home (or in other people's homes or eldercare facilities): those who care for children and those who look after older people and people with disabilities who need the assistance of health aides.

This work, historically done by women, has generally been unpaid when the worker is a family member and poorly paid when done by a professional. Childcare workers, for example, earn less than $24,000 a year on average; home healthcare aides, just over that amount.

Women's Work

Speaking of women's work, I suspect that the coronavirus and the attendant economic crisis are likely to affect women's lives in ways that will last at least a generation, if not beyond.

Middle-class feminists of the 1970s came of age in a United States where it was expected that they would marry and spend their days caring for a house, a husband, and their children. Men were the makers. Women were the "homemakers." Their work was considered -- even by Marxist economists -- "non-productive," because it did not seem to contribute to the real economy, the place where myriad widgets are produced, transported, and sold. It was seldom recognized how essential this unpaid labor in the realm of social reproduction was to a functioning economy. Without it, paid workers would not have been fed, cared for, and emotionally repaired so that they could return to another day of widget-making. Future workers would not be socialized for a life of production or reproduction, as their gender dictated.

Today, with so many women in the paid workforce, much of this work of social reproduction has been outsourced by those who can afford it to nannies, day-care workers, healthcare aides, house cleaners, or the workers who measure and pack the ingredients for meal kits to be prepared by other working women when they get home.

We didn't know it at the time, but the post-World War II period, when boomers like me grew up, was unique in U.S. history. For a brief quarter-century, even working-class families could aspire to an arrangement in which men went to work and women kept house. A combination of strong unions, a post-war economic boom, and a so-called breadwinner minimum wage kept salaries high enough to support families with only one adult in the paid labor force. Returning soldiers went to college and bought houses through the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act, also known as the G.I. Bill. New Deal programs like social security and unemployment insurance helped pad out home economies.

By the mid-1970s, however, this golden age for men, if not women, was fading. (Of course, for many African Americans and other marginalized groups, it had always only been an age of fool's gold.) Real wages stagnated and began their long, steady decline. Today's federal minimum wage, at $7.25 per hour, has remained unchanged since 2009 (something that can hardly be said about the wealth of the 1%). Far from supporting a family of four, in most parts of the country, it won't even keep a single person afloat.

Elected president in 1980, Ronald Reagan announced in his first inaugural address, "Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem." He then set about dismantling President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty programs, attacking the unions that had been the underpinning for white working-class prosperity, and generally starving the beast of government. We're still living with the legacies of that credo in, for example, the housing crisis he first touched off by deregulating savings and loan institutions and disempowering the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It's no accident that, just as real wages were falling, presidential administrations of both parties began touting the virtues of paid work for women -- at least if those women had children and no husband. Aid to Families with Dependent Children ("welfare") was another New Deal program, originally designed to provide cash assistance to widowed women raising kids on their own at a time when little paid employment was available to white women.

In the 1960s, groups like the National Welfare Rights Organization began advocating that similar benefits be extended to Black women raising children. (As a welfare rights advocate once asked me, "Why is it fine for a woman to look to a man to help her children, but not to The Man?") Not surprisingly, it wasn't until Black and Latina women began receiving the same entitlements as their white sisters that welfare became a "problem" in need of "reform."

By the mid-1990s, the fact that some Black women were receiving money from the government while not doing paid labor for an employer had been successfully reframed as a national crisis. Under Democratic President Bill Clinton, Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Reconciliation Act of 1996, a bill that then was called "welfare reform." After that, if women wanted help from The Man, they had to work for it - not by taking care of their own children, but by taking care of their children and holding down minimum-wage jobs.

Are the Kids All Right?

It's more than a little ironic, then, that the granddaughters of feminists who argued that women should have a choice about whether or not to pursue a career came to confront an economy in which women, at least ones not from wealthy families, had little choice about working for pay.

The pandemic may change that, however -- and not in a good way. One of the unfulfilled demands of liberal 1970s feminism was universal free childcare. An impossible dream, right? How could any country afford such a thing?

Wait a minute, though. What about Sweden? They have universal free childcare. That's why a Swedish friend of mine, a human rights lawyer, and her American husband who had a rare tenure track university job in San Francisco, chose to take their two children back to Sweden. Raising children is so much easier there. In the early days of second-wave feminism, some big employers even built daycare centers for their employees with children. Those days, sadly, are long gone.

Now, in the Covid-19 moment, employers are beginning to recognize the non-pandemic benefits of having employees work at home. (Why not make workers provide their own office furniture? It's a lot easier to justify if they're working at home. And why pay rent on all that real estate when so many fewer people are in the office?) While companies will profit from reduced infrastructure costs and in some cases possibly even reduced pay for employees who relocate to cheaper areas, workers with children are going to face a dilemma. With no childcare available in the foreseeable future and school re-openings dicey propositions (no matter what the president threatens), someone is going to have to watch the kids. Someone -- probably in the case of heterosexual couples, the person who is already earning less -- is going to be under pressure to reduce or give up paid labor to do the age-old unpaid (but essential) work of raising the next generation. I wonder who that someone is going to be and, without those paychecks, I also wonder how much families are going to suffer economically in increasingly tough times.

Grateful to Have a Job?

Recently, in yet another Zoom meeting, a fellow university instructor (who'd just been interrupted to help a child find a crucial toy) was discussing the administration's efforts to squeeze concessions out of faculty and staff. I was startled to hear her add, "Of course, I'm grateful they gave me the job." This got me thinking about jobs and gratitude -- and which direction thankfulness ought to flow. It seems to me that the pandemic and the epidemic of unemployment following in its wake have reinforced a common but false belief shared by many workers: the idea that we should be grateful to our employers for giving us jobs.

We're so often told that corporations and the great men behind them are Job Creators. From the fountain of their beneficence flows the dignity of work and all the benefits a job confers. Indeed, as this fairy tale goes, businesses don't primarily produce widgets or apps or even returns for shareholders. Their real product is jobs. Like many of capitalism's lies, the idea that workers should thank their employers reverses the real story: without workers, there would be no apps, no widgets, no shareholder returns. It's our effort, our skill, our diligence that gives work its dignity. It may be an old saying, but no less true for that: labor creates all wealth. Wealth does not create anything -- neither widgets, nor jobs.

I'm grateful to the universe that I have work that allows me to talk with young people about their deepest values at a moment in their lives when they're just figuring out what they value, but I am not grateful to my university employer for my underpaid, undervalued job. The gratitude should run in the other direction. Without faculty, staff, and students there would be no university. It's our labor that creates wealth, in this case a (minor) wealth of knowledge.

As of July 16th, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, 32 million Americans are receiving some kind of unemployment benefit. That number doesn't even reflect the people involuntarily working reduced hours, or those who haven't been able to apply for benefits. One thing is easy enough to predict: employers will take advantage of people's desperate need for money to demand ever more labor for ever less pay. Until an effective vaccine for the coronavirus becomes available, expect to see the emergence of a three-tier system of worker immiseration: low-paid essential workers who must leave home to do their jobs, putting themselves in significant danger in the process, while we all depend on them for sustenance; better paid people who toil at home, but whose employers will expect their hours of availability to expand to fill the waking day; and low-paid or unpaid domestic laborers, most of them women, who keep everyone else fed, clothed, and comforted.

Even when the pandemic finally ends, there's a danger that some modified version of this new system of labor exploitation might prove too profitable for employers to abandon. On the other hand, hitting the national pause button, however painfully, could give the rest of us a chance to rethink a lot of things, including the place of work, paid and unpaid, in our lives.

So, will my partner and I head for Reno in a couple of weeks? Certainly, the job of ousting Donald Trump is essential. I'm just not sure that a couple of old white ladies are essential workers in the time of Covid-19.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In two weeks, my partner and I were supposed to leave San Francisco for Reno, Nevada, where we'd be spending the next three months focused on the 2020 presidential election. As we did in 2018, we'd be working with UNITE-HERE, the hospitality industry union, only this time on the campaign to drive Donald Trump from office.

Now, however, we're not so sure we ought to go. According to information prepared for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, Nevada is among the states in the "red zone" when it comes to both confirmed cases of, and positive tests for, Covid-19. I'm 68. My partner's five years older, with a history of pneumonia. We're both active and fit (when I'm not tripping over curbs), but our ages make us more likely, if we catch the coronavirus, to get seriously ill or even die. That gives a person pause.

Then there's the fact that Joe Biden seems to have a double-digit lead over Trump nationally and at least an eight-point lead in Nevada, according to the latest polls. If things looked closer, I would cheerfully take some serious risks to dislodge that man in the White House. But does it make sense to do so if Biden is already likely to win there? Or, to put it in coronavirus-speak, would our work be essential to dumping Trump?

Essential Work?

This minor personal conundrum got me thinking about how the pandemic has exposed certain deep and unexamined assumptions about the nature and value of work in the United States.

In the ethics classes I teach undergraduates at a college here in San Francisco, we often talk about work. Ethics is, after all, about how we ought to live our lives -- and work, paid or unpaid, constitutes a big part of most of those lives. Inevitably, the conversation comes around to compensation: How much do people deserve for different kinds of work? Students tend to measure fair compensation on two scales. How many years of training and/or dollars of tuition did a worker have to invest to become "qualified" for the job? And how important is that worker's labor to the rest of society?

Even before the coronavirus hit, students would often settle on medical doctors as belonging at the top of either scale. Physicians' work is the most important, they'd argue, because they keep us alive. "Hmm..." I'd say. "How many of you went to the doctor today?" Usually not a hand would be raised. "How many of you ate something today?" All hands would go up, as students looked around the room at one another. "Maybe," I'd suggest, "a functioning society depends more on the farmworkers who plant and harvest food than on the doctors you normally might see for a checkup once a year. Not to mention the people who process and pack what we eat."

I'd also point out that the workers who pick or process our food are not really unskilled. Their work, like a surgeon's, depends on deft, quick hand movements, honed through years of practice.

Sometimes, in these discussions, I'd propose a different metric for compensation: maybe we should reserve the highest pay for people whose jobs are both essential and dangerous. Before the pandemic, that category would not have included many healthcare workers and certainly not most doctors. Even then, however, it would have encompassed farmworkers and people laboring in meat processing plants. As we've seen, in these months it is precisely such people -- often immigrants, documented or otherwise -- who have also borne some of the worst risks of virus exposure at work.

By the end of April, when it was already clear that meatpacking plants were major sites of Covid-19 infection, the president invoked the Defense Production Act to keep them open anyway. This not only meant that workers afraid to enter them could not file for unemployment payments, but that even if the owners of such dangerous workplaces wanted to shut them down, they were forbidden to do so. By mid-June, more than 24,000 meatpackers had tested positive for the virus. And just how much do these essential and deeply endangered workers earn? According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about $28,450 a year -- better than minimum wage, that is, but hardly living high on the hog (even when that's what they're handling).

You might think that farmworkers would be more protected from the virus than meatpackers, perhaps because they work outdoors. But as the New York Times has reported: "Fruit and vegetable pickers toil close to each other in fields, ride buses shoulder-to-shoulder, and sleep in cramped apartments or trailers with other laborers or several generations of their families."

Not surprisingly, then, the coronavirus has, as the Times report puts it, "ravaged" migrant farm worker communities in Florida and is starting to do the same across the country all the way to eastern Oregon. Those workers, who risk their lives through exposure not only to a pandemic but to more ordinary dangers like herbicides and pesticides so we can eat, make even less than meatpackers: on average, under $26,000 a year.

When the president uses the Defense Production Act to ensure that food workers remain in their jobs, it reveals just how important their labor truly is to the rest of us. Similarly, as shutdown orders have kept home those who can afford to stay in, or who have no choice because they no longer have jobs to go to, the pandemic has revealed the crucial nature of the labor of a large group of workers already at home (or in other people's homes or eldercare facilities): those who care for children and those who look after older people and people with disabilities who need the assistance of health aides.

This work, historically done by women, has generally been unpaid when the worker is a family member and poorly paid when done by a professional. Childcare workers, for example, earn less than $24,000 a year on average; home healthcare aides, just over that amount.

Women's Work

Speaking of women's work, I suspect that the coronavirus and the attendant economic crisis are likely to affect women's lives in ways that will last at least a generation, if not beyond.

Middle-class feminists of the 1970s came of age in a United States where it was expected that they would marry and spend their days caring for a house, a husband, and their children. Men were the makers. Women were the "homemakers." Their work was considered -- even by Marxist economists -- "non-productive," because it did not seem to contribute to the real economy, the place where myriad widgets are produced, transported, and sold. It was seldom recognized how essential this unpaid labor in the realm of social reproduction was to a functioning economy. Without it, paid workers would not have been fed, cared for, and emotionally repaired so that they could return to another day of widget-making. Future workers would not be socialized for a life of production or reproduction, as their gender dictated.

Today, with so many women in the paid workforce, much of this work of social reproduction has been outsourced by those who can afford it to nannies, day-care workers, healthcare aides, house cleaners, or the workers who measure and pack the ingredients for meal kits to be prepared by other working women when they get home.

We didn't know it at the time, but the post-World War II period, when boomers like me grew up, was unique in U.S. history. For a brief quarter-century, even working-class families could aspire to an arrangement in which men went to work and women kept house. A combination of strong unions, a post-war economic boom, and a so-called breadwinner minimum wage kept salaries high enough to support families with only one adult in the paid labor force. Returning soldiers went to college and bought houses through the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act, also known as the G.I. Bill. New Deal programs like social security and unemployment insurance helped pad out home economies.

By the mid-1970s, however, this golden age for men, if not women, was fading. (Of course, for many African Americans and other marginalized groups, it had always only been an age of fool's gold.) Real wages stagnated and began their long, steady decline. Today's federal minimum wage, at $7.25 per hour, has remained unchanged since 2009 (something that can hardly be said about the wealth of the 1%). Far from supporting a family of four, in most parts of the country, it won't even keep a single person afloat.

Elected president in 1980, Ronald Reagan announced in his first inaugural address, "Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem." He then set about dismantling President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty programs, attacking the unions that had been the underpinning for white working-class prosperity, and generally starving the beast of government. We're still living with the legacies of that credo in, for example, the housing crisis he first touched off by deregulating savings and loan institutions and disempowering the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It's no accident that, just as real wages were falling, presidential administrations of both parties began touting the virtues of paid work for women -- at least if those women had children and no husband. Aid to Families with Dependent Children ("welfare") was another New Deal program, originally designed to provide cash assistance to widowed women raising kids on their own at a time when little paid employment was available to white women.

In the 1960s, groups like the National Welfare Rights Organization began advocating that similar benefits be extended to Black women raising children. (As a welfare rights advocate once asked me, "Why is it fine for a woman to look to a man to help her children, but not to The Man?") Not surprisingly, it wasn't until Black and Latina women began receiving the same entitlements as their white sisters that welfare became a "problem" in need of "reform."

By the mid-1990s, the fact that some Black women were receiving money from the government while not doing paid labor for an employer had been successfully reframed as a national crisis. Under Democratic President Bill Clinton, Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Reconciliation Act of 1996, a bill that then was called "welfare reform." After that, if women wanted help from The Man, they had to work for it - not by taking care of their own children, but by taking care of their children and holding down minimum-wage jobs.

Are the Kids All Right?

It's more than a little ironic, then, that the granddaughters of feminists who argued that women should have a choice about whether or not to pursue a career came to confront an economy in which women, at least ones not from wealthy families, had little choice about working for pay.

The pandemic may change that, however -- and not in a good way. One of the unfulfilled demands of liberal 1970s feminism was universal free childcare. An impossible dream, right? How could any country afford such a thing?

Wait a minute, though. What about Sweden? They have universal free childcare. That's why a Swedish friend of mine, a human rights lawyer, and her American husband who had a rare tenure track university job in San Francisco, chose to take their two children back to Sweden. Raising children is so much easier there. In the early days of second-wave feminism, some big employers even built daycare centers for their employees with children. Those days, sadly, are long gone.

Now, in the Covid-19 moment, employers are beginning to recognize the non-pandemic benefits of having employees work at home. (Why not make workers provide their own office furniture? It's a lot easier to justify if they're working at home. And why pay rent on all that real estate when so many fewer people are in the office?) While companies will profit from reduced infrastructure costs and in some cases possibly even reduced pay for employees who relocate to cheaper areas, workers with children are going to face a dilemma. With no childcare available in the foreseeable future and school re-openings dicey propositions (no matter what the president threatens), someone is going to have to watch the kids. Someone -- probably in the case of heterosexual couples, the person who is already earning less -- is going to be under pressure to reduce or give up paid labor to do the age-old unpaid (but essential) work of raising the next generation. I wonder who that someone is going to be and, without those paychecks, I also wonder how much families are going to suffer economically in increasingly tough times.

Grateful to Have a Job?

Recently, in yet another Zoom meeting, a fellow university instructor (who'd just been interrupted to help a child find a crucial toy) was discussing the administration's efforts to squeeze concessions out of faculty and staff. I was startled to hear her add, "Of course, I'm grateful they gave me the job." This got me thinking about jobs and gratitude -- and which direction thankfulness ought to flow. It seems to me that the pandemic and the epidemic of unemployment following in its wake have reinforced a common but false belief shared by many workers: the idea that we should be grateful to our employers for giving us jobs.

We're so often told that corporations and the great men behind them are Job Creators. From the fountain of their beneficence flows the dignity of work and all the benefits a job confers. Indeed, as this fairy tale goes, businesses don't primarily produce widgets or apps or even returns for shareholders. Their real product is jobs. Like many of capitalism's lies, the idea that workers should thank their employers reverses the real story: without workers, there would be no apps, no widgets, no shareholder returns. It's our effort, our skill, our diligence that gives work its dignity. It may be an old saying, but no less true for that: labor creates all wealth. Wealth does not create anything -- neither widgets, nor jobs.

I'm grateful to the universe that I have work that allows me to talk with young people about their deepest values at a moment in their lives when they're just figuring out what they value, but I am not grateful to my university employer for my underpaid, undervalued job. The gratitude should run in the other direction. Without faculty, staff, and students there would be no university. It's our labor that creates wealth, in this case a (minor) wealth of knowledge.

As of July 16th, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, 32 million Americans are receiving some kind of unemployment benefit. That number doesn't even reflect the people involuntarily working reduced hours, or those who haven't been able to apply for benefits. One thing is easy enough to predict: employers will take advantage of people's desperate need for money to demand ever more labor for ever less pay. Until an effective vaccine for the coronavirus becomes available, expect to see the emergence of a three-tier system of worker immiseration: low-paid essential workers who must leave home to do their jobs, putting themselves in significant danger in the process, while we all depend on them for sustenance; better paid people who toil at home, but whose employers will expect their hours of availability to expand to fill the waking day; and low-paid or unpaid domestic laborers, most of them women, who keep everyone else fed, clothed, and comforted.

Even when the pandemic finally ends, there's a danger that some modified version of this new system of labor exploitation might prove too profitable for employers to abandon. On the other hand, hitting the national pause button, however painfully, could give the rest of us a chance to rethink a lot of things, including the place of work, paid and unpaid, in our lives.

So, will my partner and I head for Reno in a couple of weeks? Certainly, the job of ousting Donald Trump is essential. I'm just not sure that a couple of old white ladies are essential workers in the time of Covid-19.

In two weeks, my partner and I were supposed to leave San Francisco for Reno, Nevada, where we'd be spending the next three months focused on the 2020 presidential election. As we did in 2018, we'd be working with UNITE-HERE, the hospitality industry union, only this time on the campaign to drive Donald Trump from office.

Now, however, we're not so sure we ought to go. According to information prepared for the White House Coronavirus Task Force, Nevada is among the states in the "red zone" when it comes to both confirmed cases of, and positive tests for, Covid-19. I'm 68. My partner's five years older, with a history of pneumonia. We're both active and fit (when I'm not tripping over curbs), but our ages make us more likely, if we catch the coronavirus, to get seriously ill or even die. That gives a person pause.

Then there's the fact that Joe Biden seems to have a double-digit lead over Trump nationally and at least an eight-point lead in Nevada, according to the latest polls. If things looked closer, I would cheerfully take some serious risks to dislodge that man in the White House. But does it make sense to do so if Biden is already likely to win there? Or, to put it in coronavirus-speak, would our work be essential to dumping Trump?

Essential Work?

This minor personal conundrum got me thinking about how the pandemic has exposed certain deep and unexamined assumptions about the nature and value of work in the United States.

In the ethics classes I teach undergraduates at a college here in San Francisco, we often talk about work. Ethics is, after all, about how we ought to live our lives -- and work, paid or unpaid, constitutes a big part of most of those lives. Inevitably, the conversation comes around to compensation: How much do people deserve for different kinds of work? Students tend to measure fair compensation on two scales. How many years of training and/or dollars of tuition did a worker have to invest to become "qualified" for the job? And how important is that worker's labor to the rest of society?

Even before the coronavirus hit, students would often settle on medical doctors as belonging at the top of either scale. Physicians' work is the most important, they'd argue, because they keep us alive. "Hmm..." I'd say. "How many of you went to the doctor today?" Usually not a hand would be raised. "How many of you ate something today?" All hands would go up, as students looked around the room at one another. "Maybe," I'd suggest, "a functioning society depends more on the farmworkers who plant and harvest food than on the doctors you normally might see for a checkup once a year. Not to mention the people who process and pack what we eat."

I'd also point out that the workers who pick or process our food are not really unskilled. Their work, like a surgeon's, depends on deft, quick hand movements, honed through years of practice.

Sometimes, in these discussions, I'd propose a different metric for compensation: maybe we should reserve the highest pay for people whose jobs are both essential and dangerous. Before the pandemic, that category would not have included many healthcare workers and certainly not most doctors. Even then, however, it would have encompassed farmworkers and people laboring in meat processing plants. As we've seen, in these months it is precisely such people -- often immigrants, documented or otherwise -- who have also borne some of the worst risks of virus exposure at work.

By the end of April, when it was already clear that meatpacking plants were major sites of Covid-19 infection, the president invoked the Defense Production Act to keep them open anyway. This not only meant that workers afraid to enter them could not file for unemployment payments, but that even if the owners of such dangerous workplaces wanted to shut them down, they were forbidden to do so. By mid-June, more than 24,000 meatpackers had tested positive for the virus. And just how much do these essential and deeply endangered workers earn? According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, about $28,450 a year -- better than minimum wage, that is, but hardly living high on the hog (even when that's what they're handling).

You might think that farmworkers would be more protected from the virus than meatpackers, perhaps because they work outdoors. But as the New York Times has reported: "Fruit and vegetable pickers toil close to each other in fields, ride buses shoulder-to-shoulder, and sleep in cramped apartments or trailers with other laborers or several generations of their families."

Not surprisingly, then, the coronavirus has, as the Times report puts it, "ravaged" migrant farm worker communities in Florida and is starting to do the same across the country all the way to eastern Oregon. Those workers, who risk their lives through exposure not only to a pandemic but to more ordinary dangers like herbicides and pesticides so we can eat, make even less than meatpackers: on average, under $26,000 a year.

When the president uses the Defense Production Act to ensure that food workers remain in their jobs, it reveals just how important their labor truly is to the rest of us. Similarly, as shutdown orders have kept home those who can afford to stay in, or who have no choice because they no longer have jobs to go to, the pandemic has revealed the crucial nature of the labor of a large group of workers already at home (or in other people's homes or eldercare facilities): those who care for children and those who look after older people and people with disabilities who need the assistance of health aides.

This work, historically done by women, has generally been unpaid when the worker is a family member and poorly paid when done by a professional. Childcare workers, for example, earn less than $24,000 a year on average; home healthcare aides, just over that amount.

Women's Work

Speaking of women's work, I suspect that the coronavirus and the attendant economic crisis are likely to affect women's lives in ways that will last at least a generation, if not beyond.

Middle-class feminists of the 1970s came of age in a United States where it was expected that they would marry and spend their days caring for a house, a husband, and their children. Men were the makers. Women were the "homemakers." Their work was considered -- even by Marxist economists -- "non-productive," because it did not seem to contribute to the real economy, the place where myriad widgets are produced, transported, and sold. It was seldom recognized how essential this unpaid labor in the realm of social reproduction was to a functioning economy. Without it, paid workers would not have been fed, cared for, and emotionally repaired so that they could return to another day of widget-making. Future workers would not be socialized for a life of production or reproduction, as their gender dictated.

Today, with so many women in the paid workforce, much of this work of social reproduction has been outsourced by those who can afford it to nannies, day-care workers, healthcare aides, house cleaners, or the workers who measure and pack the ingredients for meal kits to be prepared by other working women when they get home.

We didn't know it at the time, but the post-World War II period, when boomers like me grew up, was unique in U.S. history. For a brief quarter-century, even working-class families could aspire to an arrangement in which men went to work and women kept house. A combination of strong unions, a post-war economic boom, and a so-called breadwinner minimum wage kept salaries high enough to support families with only one adult in the paid labor force. Returning soldiers went to college and bought houses through the 1944 Servicemen's Readjustment Act, also known as the G.I. Bill. New Deal programs like social security and unemployment insurance helped pad out home economies.

By the mid-1970s, however, this golden age for men, if not women, was fading. (Of course, for many African Americans and other marginalized groups, it had always only been an age of fool's gold.) Real wages stagnated and began their long, steady decline. Today's federal minimum wage, at $7.25 per hour, has remained unchanged since 2009 (something that can hardly be said about the wealth of the 1%). Far from supporting a family of four, in most parts of the country, it won't even keep a single person afloat.

Elected president in 1980, Ronald Reagan announced in his first inaugural address, "Government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem." He then set about dismantling President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty programs, attacking the unions that had been the underpinning for white working-class prosperity, and generally starving the beast of government. We're still living with the legacies of that credo in, for example, the housing crisis he first touched off by deregulating savings and loan institutions and disempowering the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

It's no accident that, just as real wages were falling, presidential administrations of both parties began touting the virtues of paid work for women -- at least if those women had children and no husband. Aid to Families with Dependent Children ("welfare") was another New Deal program, originally designed to provide cash assistance to widowed women raising kids on their own at a time when little paid employment was available to white women.

In the 1960s, groups like the National Welfare Rights Organization began advocating that similar benefits be extended to Black women raising children. (As a welfare rights advocate once asked me, "Why is it fine for a woman to look to a man to help her children, but not to The Man?") Not surprisingly, it wasn't until Black and Latina women began receiving the same entitlements as their white sisters that welfare became a "problem" in need of "reform."

By the mid-1990s, the fact that some Black women were receiving money from the government while not doing paid labor for an employer had been successfully reframed as a national crisis. Under Democratic President Bill Clinton, Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Reconciliation Act of 1996, a bill that then was called "welfare reform." After that, if women wanted help from The Man, they had to work for it - not by taking care of their own children, but by taking care of their children and holding down minimum-wage jobs.

Are the Kids All Right?

It's more than a little ironic, then, that the granddaughters of feminists who argued that women should have a choice about whether or not to pursue a career came to confront an economy in which women, at least ones not from wealthy families, had little choice about working for pay.

The pandemic may change that, however -- and not in a good way. One of the unfulfilled demands of liberal 1970s feminism was universal free childcare. An impossible dream, right? How could any country afford such a thing?

Wait a minute, though. What about Sweden? They have universal free childcare. That's why a Swedish friend of mine, a human rights lawyer, and her American husband who had a rare tenure track university job in San Francisco, chose to take their two children back to Sweden. Raising children is so much easier there. In the early days of second-wave feminism, some big employers even built daycare centers for their employees with children. Those days, sadly, are long gone.

Now, in the Covid-19 moment, employers are beginning to recognize the non-pandemic benefits of having employees work at home. (Why not make workers provide their own office furniture? It's a lot easier to justify if they're working at home. And why pay rent on all that real estate when so many fewer people are in the office?) While companies will profit from reduced infrastructure costs and in some cases possibly even reduced pay for employees who relocate to cheaper areas, workers with children are going to face a dilemma. With no childcare available in the foreseeable future and school re-openings dicey propositions (no matter what the president threatens), someone is going to have to watch the kids. Someone -- probably in the case of heterosexual couples, the person who is already earning less -- is going to be under pressure to reduce or give up paid labor to do the age-old unpaid (but essential) work of raising the next generation. I wonder who that someone is going to be and, without those paychecks, I also wonder how much families are going to suffer economically in increasingly tough times.

Grateful to Have a Job?

Recently, in yet another Zoom meeting, a fellow university instructor (who'd just been interrupted to help a child find a crucial toy) was discussing the administration's efforts to squeeze concessions out of faculty and staff. I was startled to hear her add, "Of course, I'm grateful they gave me the job." This got me thinking about jobs and gratitude -- and which direction thankfulness ought to flow. It seems to me that the pandemic and the epidemic of unemployment following in its wake have reinforced a common but false belief shared by many workers: the idea that we should be grateful to our employers for giving us jobs.

We're so often told that corporations and the great men behind them are Job Creators. From the fountain of their beneficence flows the dignity of work and all the benefits a job confers. Indeed, as this fairy tale goes, businesses don't primarily produce widgets or apps or even returns for shareholders. Their real product is jobs. Like many of capitalism's lies, the idea that workers should thank their employers reverses the real story: without workers, there would be no apps, no widgets, no shareholder returns. It's our effort, our skill, our diligence that gives work its dignity. It may be an old saying, but no less true for that: labor creates all wealth. Wealth does not create anything -- neither widgets, nor jobs.

I'm grateful to the universe that I have work that allows me to talk with young people about their deepest values at a moment in their lives when they're just figuring out what they value, but I am not grateful to my university employer for my underpaid, undervalued job. The gratitude should run in the other direction. Without faculty, staff, and students there would be no university. It's our labor that creates wealth, in this case a (minor) wealth of knowledge.

As of July 16th, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, 32 million Americans are receiving some kind of unemployment benefit. That number doesn't even reflect the people involuntarily working reduced hours, or those who haven't been able to apply for benefits. One thing is easy enough to predict: employers will take advantage of people's desperate need for money to demand ever more labor for ever less pay. Until an effective vaccine for the coronavirus becomes available, expect to see the emergence of a three-tier system of worker immiseration: low-paid essential workers who must leave home to do their jobs, putting themselves in significant danger in the process, while we all depend on them for sustenance; better paid people who toil at home, but whose employers will expect their hours of availability to expand to fill the waking day; and low-paid or unpaid domestic laborers, most of them women, who keep everyone else fed, clothed, and comforted.

Even when the pandemic finally ends, there's a danger that some modified version of this new system of labor exploitation might prove too profitable for employers to abandon. On the other hand, hitting the national pause button, however painfully, could give the rest of us a chance to rethink a lot of things, including the place of work, paid and unpaid, in our lives.

So, will my partner and I head for Reno in a couple of weeks? Certainly, the job of ousting Donald Trump is essential. I'm just not sure that a couple of old white ladies are essential workers in the time of Covid-19.