SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

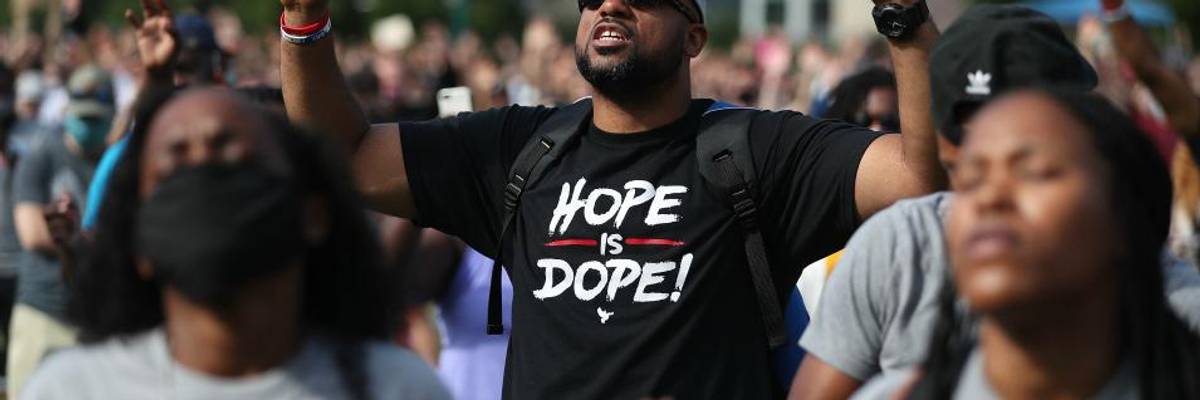

People pray together during a Juneteenth event Organized by the One Race Movement at Centennial Olympic Park on June 19, 2020 in Atlanta, Georgia. Juneteenth commemorates June 19, 1865, when a Union general read orders in Galveston, Texas stating all enslaved people in Texas were free according to federal law.

In the following interview, veteran journalist Bill Moyers talks with Rev. James Forbes, a passionate advocate of celebrating Friday, June 19 as Juneteenth--the day in 1865 when the last of America's slaves learned they were free. Because many states had refused to end slavery when President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation two and a half years earlier, it took that long before Union troops landed in Texas with news that the Civil War was over and the quarter-million slaves in Texas were slaves no more. Since then, descendants of those former slaves have celebrated Juneteenth as their Independence Day. For the last five years Rev. Dr. James Forbes--senior minister emeritus of the city's historic Riverside Church--has organized an acclaimed Juneteenth celebration in New York City, twice now at Carnegie Hall, this year online.

Listen:

BILL MOYERS: Hi Jim. This is Bill Moyers. How are you?

JAMES FORBES: I'm doing very well, thank you.

BILL MOYERS: Good. Good to talk to you. I've known you a long time now and I've watched as you've done more than anyone I know to press the case for celebrating Juneteenth as an extraordinary day. This is your sixth occasion coming up this week, big occasion, big celebration, right?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. And it will be online for Carnegie Hall and people can tune into that.

BILL MOYERS: How does it feel to be doing it in the midst of all the Sturm und Drang happening right now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, when tragedy comes, you must make it pay dearly. So that even though there are tragic events occurring- I mean, before you can heal up from one atrocity, here comes another, all of that. My mind is focused on how there must be a divine source of the energy to help this movement to develop, particularly after George Floyd's murder. I believe that God is at work even in the awful circumstances we lament. And that the groundswell of Blacks and whites and browns gathering for protest, I think that's actually miraculous of Biblical proportions. I mean, I've been in marches, but to see the diversity in the marchers and in the protesters suggests there is a spirit dynamic at work. In these awful times, grace is manifesting itself. And that's the way I prefer to look at it. Oh, I could say, "Oh, it's getting worse. We thought we were healing up. From one funeral, here we gotta go to another." But I keep looking for a sighting of the hand of God amidst the tragic circumstances of our times.

BILL MOYERS: But something is different this time, isn't it?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, something is different-

BILL MOYERS: Was it that-

JAMES FORBES: And we will not return to business as usual after the events we have experienced this year. That's my thinking. I think that there is an ugliness in the way the administration is dealing with the pandemic, dealing with protests, that is allowing us to see it is not just one person, one congressman, one mayor, one governor. I think we see beneath individual actions of meanness and unkindness. I think we see that America itself as a whole system, our whole society has a malignancy of racial and class prejudice and bigotry. I think even people that have been in denial see more clearly than ever before how deserving of retribution from high places the whole culture is. And I think because we see it that way, we have a much more systemic assessment of what's going wrong. And we sense that there needs to be systemic transformation, radical revolution of values, especially as it has to do with people of color or people of lower economic status.

BILL MOYERS: Is this different, Jim, from how you experienced racism when you were growing up in North Carolina?

JAMES FORBES: I think it's different because- and it's amazing, white folks know the truth we're telling now better than they knew it before. And they cannot hide any longer from the truth of their guilt, of the continued systemic manifestations of exploitation. I think it's a wonderful thing that Black folks know that white folks know that what we're talkin' about is the same thing. That's helpful.

BILL MOYERS: I heard you say once that, "White supremacy is not just a social arrangement, it's a race-based faith." Do you remember saying that?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. Yes, it is. This is a spiritual crisis. It is a spiritual crisis because spiritual values are so less considered worthy of our attention than material matters so that it is as if we've got a whole bunch of surrogate gods, alternative deities. Our political party, money, power, our national identification, even our collective sense of victimization, if we are a particular element in the culture. These things function with the level of seriousness as if they were gods. Or at least more than the God of justice. Let me just say this, the God of justice is not the reigning deity in America anymore.

BILL MOYERS: Who's the other god that's replaced that god?

JAMES FORBES: There are- well. The president is for some people, his base. Money is for other people, who have it. Even people who feel down and out, as some evangelicals do, their own identity as a deprived segment of the society takes on almost divine status for them.

BILL MOYERS: What does it mean for faith to be race-based?

JAMES FORBES: My thinking is that a demonic presence brought the illusion of white supremacy and that people sufficiently bought into it, that our whole nation is based upon it. So that if you ask about one's world view -- if your world view is based on the fact that whites are more worthy of life than Blacks, that they are more special in the sight of the Creator because they represent something of the identity with God, that means that the same loyalty that one gives to one's faith, in general, goes to your race. And that people are almost thinking that, if whiteness does not prevail, then their whole world collapses. I think that's the way it is with people.

BILL MOYERS: You once wrote that "Given the historical power differential between Blacks and whites, Blacks are required to be attentive to the way their white counterparts see themselves in relation to people of color if they want to survive and even thrive." Is that still the way it is?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, that is so true. That is still the way it is. Well- well, it's- it's- it's on the threshold of changing. It is as if--

BILL MOYERS: You think so?

JAMES FORBES: I think so, and I think the movement is helping this change. When people walk in the street and say, "No justice, no peace," that at least is beginning to challenge whether the power can function with impunity as they do continued evil against Black people. And I think it's beginning to be challenged. That is, how long can white people enjoy the extraordinary advantage they have in this culture as they continue to treat Black people as things? I think that question is in some people's minds these days that overlooked that years ago. So at least, let me say, I've been inquiring. And I think I hear from God, after 400 years of oppression of Black people, I think I hear from God a question: "Isn't that enough blood to drink from the veins of Black people? Enough Black flesh to eat in cannibalistic ways? Ain't that enough?" But more than that, and- and see, that's the kind of mean-spirited word, but God tends to be more gentle, I think, about this. White people, do you all not know that in Blackness I have deposited some wonderful grace, which along with whatever grace there is in your whiteness, if you all could stop allowing yourselves to view yourselves as alien others of each other, you could discover- do you not know how much wonderful quality of life could be possible if Black people and white people could recognize that fundamentally they are one family? They are brothers and sisters. You- white people need to understand, do you know how much you are missing by simply making chattel property out of these folks that God said were human beings? And I think another thing I think I hear from God is that you really need to know that I am so committed, God is so committed to truth, that if you would dare to embrace the truth, you would discover that the key truth is that God's forgiveness is available. And that God's forgiveness is available, particularly to people who are prepared to follow the path of truth and justice. God's grace is available to those who are ready now to embrace the new possibility of Psalm 133, how pleasant- good and how pleasant it is for brothers and sisters to dwell together in unity. If only white people could understand how they are denying themselves some richness that God has placed in their other brothers and sisters. God will grant them pardon as they embrace the commitment of being one people together. And this matters to God, because God is ultimate relationality. I don't say that--

BILL MOYERS: What do you mean?

JAMES FORBES: -to sound like I'm preachin' to you, Bill. That is-

BILL MOYERS: Well, you were several times named one of America's 12 greatest preachers. So it's- it's all right if you- if you can't forget your--

JAMES FORBES: It's okay, it's okay, it's okay. By- by that I have to say, do you know that God, so far as I can tell, is Love, and that Love puts a premium on relationality? That is, if Black people and white people could relate to each other as brothers and sisters with mutuality of care and concern, that would make the heart of God so happy. I mean, if you just thought of it like that. That because God is ultimate relationality, the whole universe itself, all of the various pieces of it, all of the various species, all of the very generations and eons in God are one. So that those who persist in alienation and the demonization of the other, that- that does not make the heart of God, the Creator, does not grant satisfaction. It is- it is because God is ultimate relationality where all of the pieces fit, that all of the pieces- all of the eons, the sun, the moon, the stars. All of the orders of creation as they relate to each other and understand that one has impact on the possibilities of the other. It is that that I think God would wish us to see, and learn to live into and to live by.

BILL MOYERS: But do you think God forgives the policeman who kept his knee on George Floyd's neck for over 8-1/2 minutes until the breath of life left him?

JAMES FORBES: The way I answer that question is that if I were going to represent Chauvin before God, I would have to have a class action presentation. If God forgives any one of us of sins that we have committed, then we should wish that forgiveness of sin is a class action. That's why I guess I'm different. I'm not as much worried about his knee on his neck as I am following. Those who were also sitting on the brother's body, and the elephant of the systemic racism that's been sittin' on our necks for all these years. I'll have to include them in it. And I'll say this, I- I hope that semblance of justice will prevail, so that he would be incarcerated for his evil. But even if he's incarcerated, I would wish God go into the incarcerated jail. And if he were to repent for the evils that led to that behavior, I hope he might be forgiven as well.

BILL MOYERS: But what do you say to a young woman like Aalayah Eastmond? Let me tell you about her. She's 19 years old. She survived the 2018 massacre at her high school in Parkland, Florida. She became a gun control advocate, saw many legislative efforts stall. She's now been organizing protests in Washington over police violence against her Black brothers and sisters. And she said, "I'm tired. I'm literally tired. I'm tired of having to do this. We came out of Parkland vowing to change the gun laws, and nothing has really happened. We saw so many legislative efforts stall. We do our job," she said, "and then we don't see the people we vote in doing their job." And her lament was echoed by many others in that story. And I tremble for the country in this respect. If these young people once again come out of a crisis such as we've been experiencing and our system doesn't respond, our system, the whole collectivity of our system goes back to the normality before Trump, her heart is not only going to be broken. But her sense of America will be forever changed. So, how can you keep clinging to the possibilities that you have spoken of in our conversation? Because every time there has been a surge of freedom for Blacks -- after the Civil War, after the Emancipation Proclamation, after the Reconstruction, after the civil rights movement of the last century, after the first presidency of a Black president, there's always been a backlash that has sent things reeling again toward the past. How can you feel so hopeful now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, I think the way- I guess I'd have to respond to the young lady and to your question as well. What I want to do is I want to continue to keep faith with the tradition of which I am a part, and I call it Black spirituality. When I heard Kathleen Battle sing at Carnegie Hall years ago, "God, how come me here? God, how come me here? God, how come me here? I wished I'd never been born." That was a powerful moment. So what I do is, that tradition is that that's what makes us such a great gift to America; that Black people came here with that kinda capacity that in the midst of the imponderables and the inscrutables of life, we still engage in conversation with the God that we know to be real. So my first answer to the young lady is, let's say to God, "God, don't let this harvest pass unfruitful. Don't- don't- don't let what has been in the streets of America in these last few weeks be for naught." L- I mean- I mean, beat the gates of eternity. "God, you've got to let something of value emerge from this." And we hear you did it 400 years for Israel. You- you gotta do it now for Americans, Black and white. If you got a relationship with God, you can say, "God- God you got to get somethin' out of this thing this time." And then you listen to what God says, "I'm workin' on it Jim. And you've got to give me everything you've got too." We got to work on this thing together. Dr. King says, "We shall get to the promised land. I may not get there with you, but we as a people will get to the promised land." So anyway, it's interesting that you should ask this question, because there's this poem that I put together, Bill, that might seem like the best answer I could give to the question that you just asked me. It says, "Supremacists more bigoted and bold, / leaders in high places, ruthless and cold. / Why do we keep on singing hopeful songs / in the midst of hateful and brutal wrongs? / What keeps our hearts and minds from sinking down / while we are handcuffed and our spirits bound? / Do we know something others do not know? / Why couldn't we give up when hate sank so low? / Why didn't we stop protesting or cease to grieve, / when our eyes saw evil we couldn't believe? / Why do we still march with justice demands, / chanting and singing with uplifted hands? / We sing because we know, God's on the throne, / at work in everything known and unknown. / Though we won't win the battle every day, / faith trusts God to have the final say. / Whether we live or die confronting wrong, / we shall overcome for sure, that's our song." I guess that's my answer to you, man. I guess my ancestors said, "There's a God," and they used to say, "May not come when you want Him, but he's right on time." That's the gift of Black spirituality when it is sustained. Hopefulness against hope. And refusing, sort of like Job, "Though you slay me, yet shall I trust in you." I mean, what else have we got?

BILL MOYERS: What do you hope us white folks see when we see Juneteenth this week?

JAMES FORBES: I hope that white people can see there's no need to deny any longer. There's no need to lie any longer. There's no need to claim somebody else and blame somebody else for the evils of the past. They are part of our history. I hope that they would be able to see how great will be the day when we, having made peace with the evils of the past as our evils, but accept the grace of God as forgiveness, and the invitation of God to be participants in building the new reality, the new world. I hope white people can see forgiveness is available if you decide you want to be a part of the human race in unity and justice and peaceful resolve. I hope they will see the prospect of living in the forgiving grace of God, and walking toward the beloved community, or as we like to say, the more perfect union.

BILL MOYERS: James Forbes, thank you very much. And I hope you have a great Juneteenth.

JAMES FORBES: All right, Bill, thank you so very much.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

In the following interview, veteran journalist Bill Moyers talks with Rev. James Forbes, a passionate advocate of celebrating Friday, June 19 as Juneteenth--the day in 1865 when the last of America's slaves learned they were free. Because many states had refused to end slavery when President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation two and a half years earlier, it took that long before Union troops landed in Texas with news that the Civil War was over and the quarter-million slaves in Texas were slaves no more. Since then, descendants of those former slaves have celebrated Juneteenth as their Independence Day. For the last five years Rev. Dr. James Forbes--senior minister emeritus of the city's historic Riverside Church--has organized an acclaimed Juneteenth celebration in New York City, twice now at Carnegie Hall, this year online.

Listen:

BILL MOYERS: Hi Jim. This is Bill Moyers. How are you?

JAMES FORBES: I'm doing very well, thank you.

BILL MOYERS: Good. Good to talk to you. I've known you a long time now and I've watched as you've done more than anyone I know to press the case for celebrating Juneteenth as an extraordinary day. This is your sixth occasion coming up this week, big occasion, big celebration, right?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. And it will be online for Carnegie Hall and people can tune into that.

BILL MOYERS: How does it feel to be doing it in the midst of all the Sturm und Drang happening right now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, when tragedy comes, you must make it pay dearly. So that even though there are tragic events occurring- I mean, before you can heal up from one atrocity, here comes another, all of that. My mind is focused on how there must be a divine source of the energy to help this movement to develop, particularly after George Floyd's murder. I believe that God is at work even in the awful circumstances we lament. And that the groundswell of Blacks and whites and browns gathering for protest, I think that's actually miraculous of Biblical proportions. I mean, I've been in marches, but to see the diversity in the marchers and in the protesters suggests there is a spirit dynamic at work. In these awful times, grace is manifesting itself. And that's the way I prefer to look at it. Oh, I could say, "Oh, it's getting worse. We thought we were healing up. From one funeral, here we gotta go to another." But I keep looking for a sighting of the hand of God amidst the tragic circumstances of our times.

BILL MOYERS: But something is different this time, isn't it?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, something is different-

BILL MOYERS: Was it that-

JAMES FORBES: And we will not return to business as usual after the events we have experienced this year. That's my thinking. I think that there is an ugliness in the way the administration is dealing with the pandemic, dealing with protests, that is allowing us to see it is not just one person, one congressman, one mayor, one governor. I think we see beneath individual actions of meanness and unkindness. I think we see that America itself as a whole system, our whole society has a malignancy of racial and class prejudice and bigotry. I think even people that have been in denial see more clearly than ever before how deserving of retribution from high places the whole culture is. And I think because we see it that way, we have a much more systemic assessment of what's going wrong. And we sense that there needs to be systemic transformation, radical revolution of values, especially as it has to do with people of color or people of lower economic status.

BILL MOYERS: Is this different, Jim, from how you experienced racism when you were growing up in North Carolina?

JAMES FORBES: I think it's different because- and it's amazing, white folks know the truth we're telling now better than they knew it before. And they cannot hide any longer from the truth of their guilt, of the continued systemic manifestations of exploitation. I think it's a wonderful thing that Black folks know that white folks know that what we're talkin' about is the same thing. That's helpful.

BILL MOYERS: I heard you say once that, "White supremacy is not just a social arrangement, it's a race-based faith." Do you remember saying that?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. Yes, it is. This is a spiritual crisis. It is a spiritual crisis because spiritual values are so less considered worthy of our attention than material matters so that it is as if we've got a whole bunch of surrogate gods, alternative deities. Our political party, money, power, our national identification, even our collective sense of victimization, if we are a particular element in the culture. These things function with the level of seriousness as if they were gods. Or at least more than the God of justice. Let me just say this, the God of justice is not the reigning deity in America anymore.

BILL MOYERS: Who's the other god that's replaced that god?

JAMES FORBES: There are- well. The president is for some people, his base. Money is for other people, who have it. Even people who feel down and out, as some evangelicals do, their own identity as a deprived segment of the society takes on almost divine status for them.

BILL MOYERS: What does it mean for faith to be race-based?

JAMES FORBES: My thinking is that a demonic presence brought the illusion of white supremacy and that people sufficiently bought into it, that our whole nation is based upon it. So that if you ask about one's world view -- if your world view is based on the fact that whites are more worthy of life than Blacks, that they are more special in the sight of the Creator because they represent something of the identity with God, that means that the same loyalty that one gives to one's faith, in general, goes to your race. And that people are almost thinking that, if whiteness does not prevail, then their whole world collapses. I think that's the way it is with people.

BILL MOYERS: You once wrote that "Given the historical power differential between Blacks and whites, Blacks are required to be attentive to the way their white counterparts see themselves in relation to people of color if they want to survive and even thrive." Is that still the way it is?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, that is so true. That is still the way it is. Well- well, it's- it's- it's on the threshold of changing. It is as if--

BILL MOYERS: You think so?

JAMES FORBES: I think so, and I think the movement is helping this change. When people walk in the street and say, "No justice, no peace," that at least is beginning to challenge whether the power can function with impunity as they do continued evil against Black people. And I think it's beginning to be challenged. That is, how long can white people enjoy the extraordinary advantage they have in this culture as they continue to treat Black people as things? I think that question is in some people's minds these days that overlooked that years ago. So at least, let me say, I've been inquiring. And I think I hear from God, after 400 years of oppression of Black people, I think I hear from God a question: "Isn't that enough blood to drink from the veins of Black people? Enough Black flesh to eat in cannibalistic ways? Ain't that enough?" But more than that, and- and see, that's the kind of mean-spirited word, but God tends to be more gentle, I think, about this. White people, do you all not know that in Blackness I have deposited some wonderful grace, which along with whatever grace there is in your whiteness, if you all could stop allowing yourselves to view yourselves as alien others of each other, you could discover- do you not know how much wonderful quality of life could be possible if Black people and white people could recognize that fundamentally they are one family? They are brothers and sisters. You- white people need to understand, do you know how much you are missing by simply making chattel property out of these folks that God said were human beings? And I think another thing I think I hear from God is that you really need to know that I am so committed, God is so committed to truth, that if you would dare to embrace the truth, you would discover that the key truth is that God's forgiveness is available. And that God's forgiveness is available, particularly to people who are prepared to follow the path of truth and justice. God's grace is available to those who are ready now to embrace the new possibility of Psalm 133, how pleasant- good and how pleasant it is for brothers and sisters to dwell together in unity. If only white people could understand how they are denying themselves some richness that God has placed in their other brothers and sisters. God will grant them pardon as they embrace the commitment of being one people together. And this matters to God, because God is ultimate relationality. I don't say that--

BILL MOYERS: What do you mean?

JAMES FORBES: -to sound like I'm preachin' to you, Bill. That is-

BILL MOYERS: Well, you were several times named one of America's 12 greatest preachers. So it's- it's all right if you- if you can't forget your--

JAMES FORBES: It's okay, it's okay, it's okay. By- by that I have to say, do you know that God, so far as I can tell, is Love, and that Love puts a premium on relationality? That is, if Black people and white people could relate to each other as brothers and sisters with mutuality of care and concern, that would make the heart of God so happy. I mean, if you just thought of it like that. That because God is ultimate relationality, the whole universe itself, all of the various pieces of it, all of the various species, all of the very generations and eons in God are one. So that those who persist in alienation and the demonization of the other, that- that does not make the heart of God, the Creator, does not grant satisfaction. It is- it is because God is ultimate relationality where all of the pieces fit, that all of the pieces- all of the eons, the sun, the moon, the stars. All of the orders of creation as they relate to each other and understand that one has impact on the possibilities of the other. It is that that I think God would wish us to see, and learn to live into and to live by.

BILL MOYERS: But do you think God forgives the policeman who kept his knee on George Floyd's neck for over 8-1/2 minutes until the breath of life left him?

JAMES FORBES: The way I answer that question is that if I were going to represent Chauvin before God, I would have to have a class action presentation. If God forgives any one of us of sins that we have committed, then we should wish that forgiveness of sin is a class action. That's why I guess I'm different. I'm not as much worried about his knee on his neck as I am following. Those who were also sitting on the brother's body, and the elephant of the systemic racism that's been sittin' on our necks for all these years. I'll have to include them in it. And I'll say this, I- I hope that semblance of justice will prevail, so that he would be incarcerated for his evil. But even if he's incarcerated, I would wish God go into the incarcerated jail. And if he were to repent for the evils that led to that behavior, I hope he might be forgiven as well.

BILL MOYERS: But what do you say to a young woman like Aalayah Eastmond? Let me tell you about her. She's 19 years old. She survived the 2018 massacre at her high school in Parkland, Florida. She became a gun control advocate, saw many legislative efforts stall. She's now been organizing protests in Washington over police violence against her Black brothers and sisters. And she said, "I'm tired. I'm literally tired. I'm tired of having to do this. We came out of Parkland vowing to change the gun laws, and nothing has really happened. We saw so many legislative efforts stall. We do our job," she said, "and then we don't see the people we vote in doing their job." And her lament was echoed by many others in that story. And I tremble for the country in this respect. If these young people once again come out of a crisis such as we've been experiencing and our system doesn't respond, our system, the whole collectivity of our system goes back to the normality before Trump, her heart is not only going to be broken. But her sense of America will be forever changed. So, how can you keep clinging to the possibilities that you have spoken of in our conversation? Because every time there has been a surge of freedom for Blacks -- after the Civil War, after the Emancipation Proclamation, after the Reconstruction, after the civil rights movement of the last century, after the first presidency of a Black president, there's always been a backlash that has sent things reeling again toward the past. How can you feel so hopeful now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, I think the way- I guess I'd have to respond to the young lady and to your question as well. What I want to do is I want to continue to keep faith with the tradition of which I am a part, and I call it Black spirituality. When I heard Kathleen Battle sing at Carnegie Hall years ago, "God, how come me here? God, how come me here? God, how come me here? I wished I'd never been born." That was a powerful moment. So what I do is, that tradition is that that's what makes us such a great gift to America; that Black people came here with that kinda capacity that in the midst of the imponderables and the inscrutables of life, we still engage in conversation with the God that we know to be real. So my first answer to the young lady is, let's say to God, "God, don't let this harvest pass unfruitful. Don't- don't- don't let what has been in the streets of America in these last few weeks be for naught." L- I mean- I mean, beat the gates of eternity. "God, you've got to let something of value emerge from this." And we hear you did it 400 years for Israel. You- you gotta do it now for Americans, Black and white. If you got a relationship with God, you can say, "God- God you got to get somethin' out of this thing this time." And then you listen to what God says, "I'm workin' on it Jim. And you've got to give me everything you've got too." We got to work on this thing together. Dr. King says, "We shall get to the promised land. I may not get there with you, but we as a people will get to the promised land." So anyway, it's interesting that you should ask this question, because there's this poem that I put together, Bill, that might seem like the best answer I could give to the question that you just asked me. It says, "Supremacists more bigoted and bold, / leaders in high places, ruthless and cold. / Why do we keep on singing hopeful songs / in the midst of hateful and brutal wrongs? / What keeps our hearts and minds from sinking down / while we are handcuffed and our spirits bound? / Do we know something others do not know? / Why couldn't we give up when hate sank so low? / Why didn't we stop protesting or cease to grieve, / when our eyes saw evil we couldn't believe? / Why do we still march with justice demands, / chanting and singing with uplifted hands? / We sing because we know, God's on the throne, / at work in everything known and unknown. / Though we won't win the battle every day, / faith trusts God to have the final say. / Whether we live or die confronting wrong, / we shall overcome for sure, that's our song." I guess that's my answer to you, man. I guess my ancestors said, "There's a God," and they used to say, "May not come when you want Him, but he's right on time." That's the gift of Black spirituality when it is sustained. Hopefulness against hope. And refusing, sort of like Job, "Though you slay me, yet shall I trust in you." I mean, what else have we got?

BILL MOYERS: What do you hope us white folks see when we see Juneteenth this week?

JAMES FORBES: I hope that white people can see there's no need to deny any longer. There's no need to lie any longer. There's no need to claim somebody else and blame somebody else for the evils of the past. They are part of our history. I hope that they would be able to see how great will be the day when we, having made peace with the evils of the past as our evils, but accept the grace of God as forgiveness, and the invitation of God to be participants in building the new reality, the new world. I hope white people can see forgiveness is available if you decide you want to be a part of the human race in unity and justice and peaceful resolve. I hope they will see the prospect of living in the forgiving grace of God, and walking toward the beloved community, or as we like to say, the more perfect union.

BILL MOYERS: James Forbes, thank you very much. And I hope you have a great Juneteenth.

JAMES FORBES: All right, Bill, thank you so very much.

In the following interview, veteran journalist Bill Moyers talks with Rev. James Forbes, a passionate advocate of celebrating Friday, June 19 as Juneteenth--the day in 1865 when the last of America's slaves learned they were free. Because many states had refused to end slavery when President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation two and a half years earlier, it took that long before Union troops landed in Texas with news that the Civil War was over and the quarter-million slaves in Texas were slaves no more. Since then, descendants of those former slaves have celebrated Juneteenth as their Independence Day. For the last five years Rev. Dr. James Forbes--senior minister emeritus of the city's historic Riverside Church--has organized an acclaimed Juneteenth celebration in New York City, twice now at Carnegie Hall, this year online.

Listen:

BILL MOYERS: Hi Jim. This is Bill Moyers. How are you?

JAMES FORBES: I'm doing very well, thank you.

BILL MOYERS: Good. Good to talk to you. I've known you a long time now and I've watched as you've done more than anyone I know to press the case for celebrating Juneteenth as an extraordinary day. This is your sixth occasion coming up this week, big occasion, big celebration, right?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. And it will be online for Carnegie Hall and people can tune into that.

BILL MOYERS: How does it feel to be doing it in the midst of all the Sturm und Drang happening right now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, when tragedy comes, you must make it pay dearly. So that even though there are tragic events occurring- I mean, before you can heal up from one atrocity, here comes another, all of that. My mind is focused on how there must be a divine source of the energy to help this movement to develop, particularly after George Floyd's murder. I believe that God is at work even in the awful circumstances we lament. And that the groundswell of Blacks and whites and browns gathering for protest, I think that's actually miraculous of Biblical proportions. I mean, I've been in marches, but to see the diversity in the marchers and in the protesters suggests there is a spirit dynamic at work. In these awful times, grace is manifesting itself. And that's the way I prefer to look at it. Oh, I could say, "Oh, it's getting worse. We thought we were healing up. From one funeral, here we gotta go to another." But I keep looking for a sighting of the hand of God amidst the tragic circumstances of our times.

BILL MOYERS: But something is different this time, isn't it?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, something is different-

BILL MOYERS: Was it that-

JAMES FORBES: And we will not return to business as usual after the events we have experienced this year. That's my thinking. I think that there is an ugliness in the way the administration is dealing with the pandemic, dealing with protests, that is allowing us to see it is not just one person, one congressman, one mayor, one governor. I think we see beneath individual actions of meanness and unkindness. I think we see that America itself as a whole system, our whole society has a malignancy of racial and class prejudice and bigotry. I think even people that have been in denial see more clearly than ever before how deserving of retribution from high places the whole culture is. And I think because we see it that way, we have a much more systemic assessment of what's going wrong. And we sense that there needs to be systemic transformation, radical revolution of values, especially as it has to do with people of color or people of lower economic status.

BILL MOYERS: Is this different, Jim, from how you experienced racism when you were growing up in North Carolina?

JAMES FORBES: I think it's different because- and it's amazing, white folks know the truth we're telling now better than they knew it before. And they cannot hide any longer from the truth of their guilt, of the continued systemic manifestations of exploitation. I think it's a wonderful thing that Black folks know that white folks know that what we're talkin' about is the same thing. That's helpful.

BILL MOYERS: I heard you say once that, "White supremacy is not just a social arrangement, it's a race-based faith." Do you remember saying that?

JAMES FORBES: Yes. Yes, it is. This is a spiritual crisis. It is a spiritual crisis because spiritual values are so less considered worthy of our attention than material matters so that it is as if we've got a whole bunch of surrogate gods, alternative deities. Our political party, money, power, our national identification, even our collective sense of victimization, if we are a particular element in the culture. These things function with the level of seriousness as if they were gods. Or at least more than the God of justice. Let me just say this, the God of justice is not the reigning deity in America anymore.

BILL MOYERS: Who's the other god that's replaced that god?

JAMES FORBES: There are- well. The president is for some people, his base. Money is for other people, who have it. Even people who feel down and out, as some evangelicals do, their own identity as a deprived segment of the society takes on almost divine status for them.

BILL MOYERS: What does it mean for faith to be race-based?

JAMES FORBES: My thinking is that a demonic presence brought the illusion of white supremacy and that people sufficiently bought into it, that our whole nation is based upon it. So that if you ask about one's world view -- if your world view is based on the fact that whites are more worthy of life than Blacks, that they are more special in the sight of the Creator because they represent something of the identity with God, that means that the same loyalty that one gives to one's faith, in general, goes to your race. And that people are almost thinking that, if whiteness does not prevail, then their whole world collapses. I think that's the way it is with people.

BILL MOYERS: You once wrote that "Given the historical power differential between Blacks and whites, Blacks are required to be attentive to the way their white counterparts see themselves in relation to people of color if they want to survive and even thrive." Is that still the way it is?

JAMES FORBES: Yes, that is so true. That is still the way it is. Well- well, it's- it's- it's on the threshold of changing. It is as if--

BILL MOYERS: You think so?

JAMES FORBES: I think so, and I think the movement is helping this change. When people walk in the street and say, "No justice, no peace," that at least is beginning to challenge whether the power can function with impunity as they do continued evil against Black people. And I think it's beginning to be challenged. That is, how long can white people enjoy the extraordinary advantage they have in this culture as they continue to treat Black people as things? I think that question is in some people's minds these days that overlooked that years ago. So at least, let me say, I've been inquiring. And I think I hear from God, after 400 years of oppression of Black people, I think I hear from God a question: "Isn't that enough blood to drink from the veins of Black people? Enough Black flesh to eat in cannibalistic ways? Ain't that enough?" But more than that, and- and see, that's the kind of mean-spirited word, but God tends to be more gentle, I think, about this. White people, do you all not know that in Blackness I have deposited some wonderful grace, which along with whatever grace there is in your whiteness, if you all could stop allowing yourselves to view yourselves as alien others of each other, you could discover- do you not know how much wonderful quality of life could be possible if Black people and white people could recognize that fundamentally they are one family? They are brothers and sisters. You- white people need to understand, do you know how much you are missing by simply making chattel property out of these folks that God said were human beings? And I think another thing I think I hear from God is that you really need to know that I am so committed, God is so committed to truth, that if you would dare to embrace the truth, you would discover that the key truth is that God's forgiveness is available. And that God's forgiveness is available, particularly to people who are prepared to follow the path of truth and justice. God's grace is available to those who are ready now to embrace the new possibility of Psalm 133, how pleasant- good and how pleasant it is for brothers and sisters to dwell together in unity. If only white people could understand how they are denying themselves some richness that God has placed in their other brothers and sisters. God will grant them pardon as they embrace the commitment of being one people together. And this matters to God, because God is ultimate relationality. I don't say that--

BILL MOYERS: What do you mean?

JAMES FORBES: -to sound like I'm preachin' to you, Bill. That is-

BILL MOYERS: Well, you were several times named one of America's 12 greatest preachers. So it's- it's all right if you- if you can't forget your--

JAMES FORBES: It's okay, it's okay, it's okay. By- by that I have to say, do you know that God, so far as I can tell, is Love, and that Love puts a premium on relationality? That is, if Black people and white people could relate to each other as brothers and sisters with mutuality of care and concern, that would make the heart of God so happy. I mean, if you just thought of it like that. That because God is ultimate relationality, the whole universe itself, all of the various pieces of it, all of the various species, all of the very generations and eons in God are one. So that those who persist in alienation and the demonization of the other, that- that does not make the heart of God, the Creator, does not grant satisfaction. It is- it is because God is ultimate relationality where all of the pieces fit, that all of the pieces- all of the eons, the sun, the moon, the stars. All of the orders of creation as they relate to each other and understand that one has impact on the possibilities of the other. It is that that I think God would wish us to see, and learn to live into and to live by.

BILL MOYERS: But do you think God forgives the policeman who kept his knee on George Floyd's neck for over 8-1/2 minutes until the breath of life left him?

JAMES FORBES: The way I answer that question is that if I were going to represent Chauvin before God, I would have to have a class action presentation. If God forgives any one of us of sins that we have committed, then we should wish that forgiveness of sin is a class action. That's why I guess I'm different. I'm not as much worried about his knee on his neck as I am following. Those who were also sitting on the brother's body, and the elephant of the systemic racism that's been sittin' on our necks for all these years. I'll have to include them in it. And I'll say this, I- I hope that semblance of justice will prevail, so that he would be incarcerated for his evil. But even if he's incarcerated, I would wish God go into the incarcerated jail. And if he were to repent for the evils that led to that behavior, I hope he might be forgiven as well.

BILL MOYERS: But what do you say to a young woman like Aalayah Eastmond? Let me tell you about her. She's 19 years old. She survived the 2018 massacre at her high school in Parkland, Florida. She became a gun control advocate, saw many legislative efforts stall. She's now been organizing protests in Washington over police violence against her Black brothers and sisters. And she said, "I'm tired. I'm literally tired. I'm tired of having to do this. We came out of Parkland vowing to change the gun laws, and nothing has really happened. We saw so many legislative efforts stall. We do our job," she said, "and then we don't see the people we vote in doing their job." And her lament was echoed by many others in that story. And I tremble for the country in this respect. If these young people once again come out of a crisis such as we've been experiencing and our system doesn't respond, our system, the whole collectivity of our system goes back to the normality before Trump, her heart is not only going to be broken. But her sense of America will be forever changed. So, how can you keep clinging to the possibilities that you have spoken of in our conversation? Because every time there has been a surge of freedom for Blacks -- after the Civil War, after the Emancipation Proclamation, after the Reconstruction, after the civil rights movement of the last century, after the first presidency of a Black president, there's always been a backlash that has sent things reeling again toward the past. How can you feel so hopeful now?

JAMES FORBES: Well, I think the way- I guess I'd have to respond to the young lady and to your question as well. What I want to do is I want to continue to keep faith with the tradition of which I am a part, and I call it Black spirituality. When I heard Kathleen Battle sing at Carnegie Hall years ago, "God, how come me here? God, how come me here? God, how come me here? I wished I'd never been born." That was a powerful moment. So what I do is, that tradition is that that's what makes us such a great gift to America; that Black people came here with that kinda capacity that in the midst of the imponderables and the inscrutables of life, we still engage in conversation with the God that we know to be real. So my first answer to the young lady is, let's say to God, "God, don't let this harvest pass unfruitful. Don't- don't- don't let what has been in the streets of America in these last few weeks be for naught." L- I mean- I mean, beat the gates of eternity. "God, you've got to let something of value emerge from this." And we hear you did it 400 years for Israel. You- you gotta do it now for Americans, Black and white. If you got a relationship with God, you can say, "God- God you got to get somethin' out of this thing this time." And then you listen to what God says, "I'm workin' on it Jim. And you've got to give me everything you've got too." We got to work on this thing together. Dr. King says, "We shall get to the promised land. I may not get there with you, but we as a people will get to the promised land." So anyway, it's interesting that you should ask this question, because there's this poem that I put together, Bill, that might seem like the best answer I could give to the question that you just asked me. It says, "Supremacists more bigoted and bold, / leaders in high places, ruthless and cold. / Why do we keep on singing hopeful songs / in the midst of hateful and brutal wrongs? / What keeps our hearts and minds from sinking down / while we are handcuffed and our spirits bound? / Do we know something others do not know? / Why couldn't we give up when hate sank so low? / Why didn't we stop protesting or cease to grieve, / when our eyes saw evil we couldn't believe? / Why do we still march with justice demands, / chanting and singing with uplifted hands? / We sing because we know, God's on the throne, / at work in everything known and unknown. / Though we won't win the battle every day, / faith trusts God to have the final say. / Whether we live or die confronting wrong, / we shall overcome for sure, that's our song." I guess that's my answer to you, man. I guess my ancestors said, "There's a God," and they used to say, "May not come when you want Him, but he's right on time." That's the gift of Black spirituality when it is sustained. Hopefulness against hope. And refusing, sort of like Job, "Though you slay me, yet shall I trust in you." I mean, what else have we got?

BILL MOYERS: What do you hope us white folks see when we see Juneteenth this week?

JAMES FORBES: I hope that white people can see there's no need to deny any longer. There's no need to lie any longer. There's no need to claim somebody else and blame somebody else for the evils of the past. They are part of our history. I hope that they would be able to see how great will be the day when we, having made peace with the evils of the past as our evils, but accept the grace of God as forgiveness, and the invitation of God to be participants in building the new reality, the new world. I hope white people can see forgiveness is available if you decide you want to be a part of the human race in unity and justice and peaceful resolve. I hope they will see the prospect of living in the forgiving grace of God, and walking toward the beloved community, or as we like to say, the more perfect union.

BILL MOYERS: James Forbes, thank you very much. And I hope you have a great Juneteenth.

JAMES FORBES: All right, Bill, thank you so very much.