SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

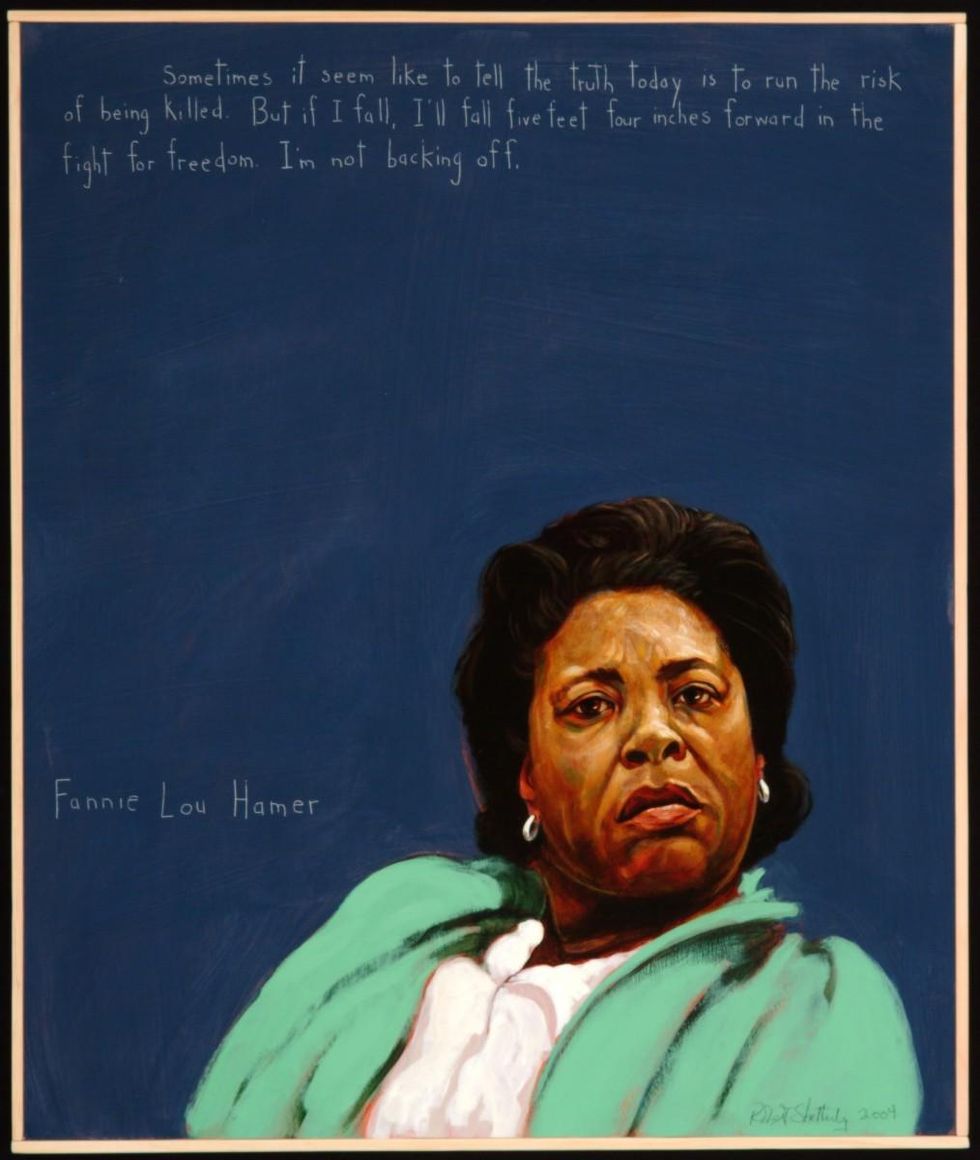

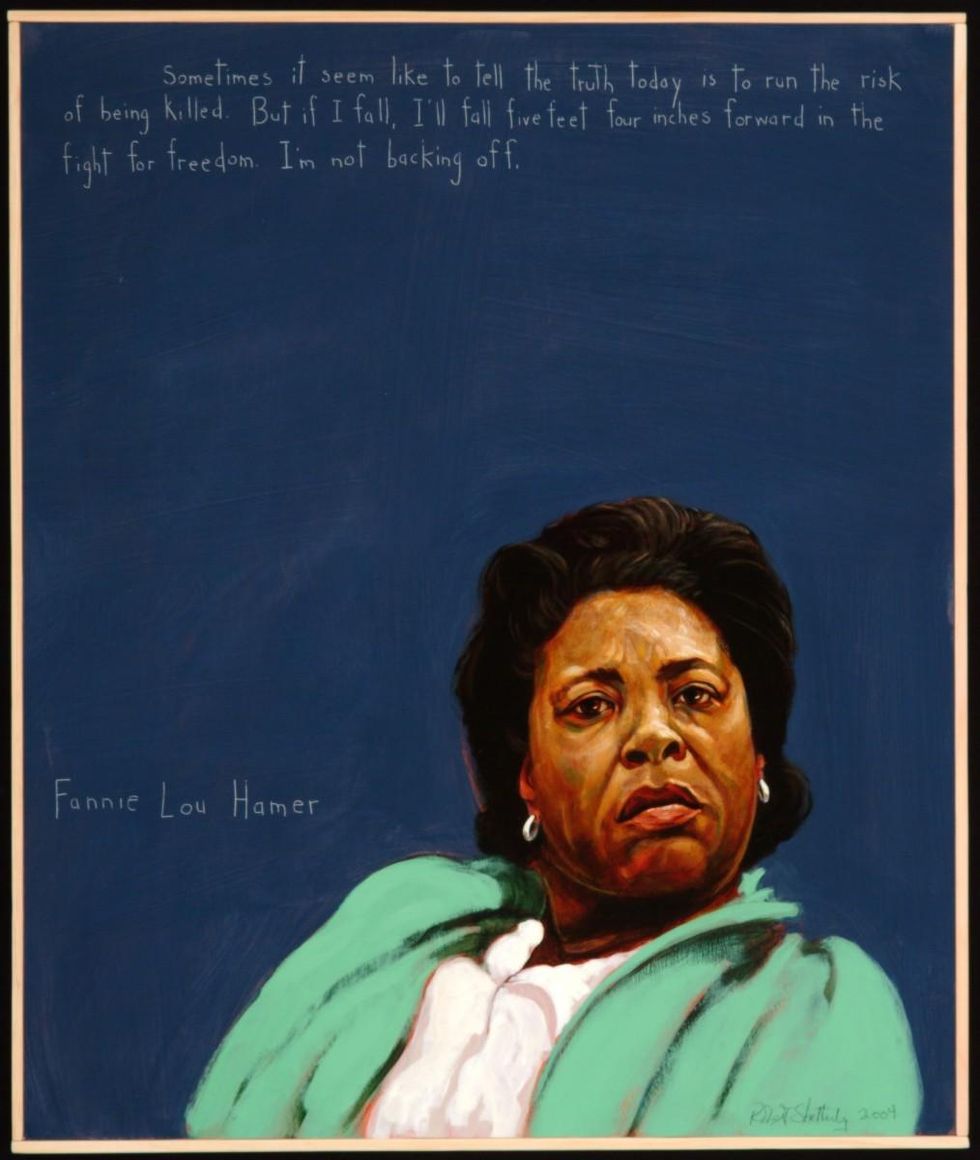

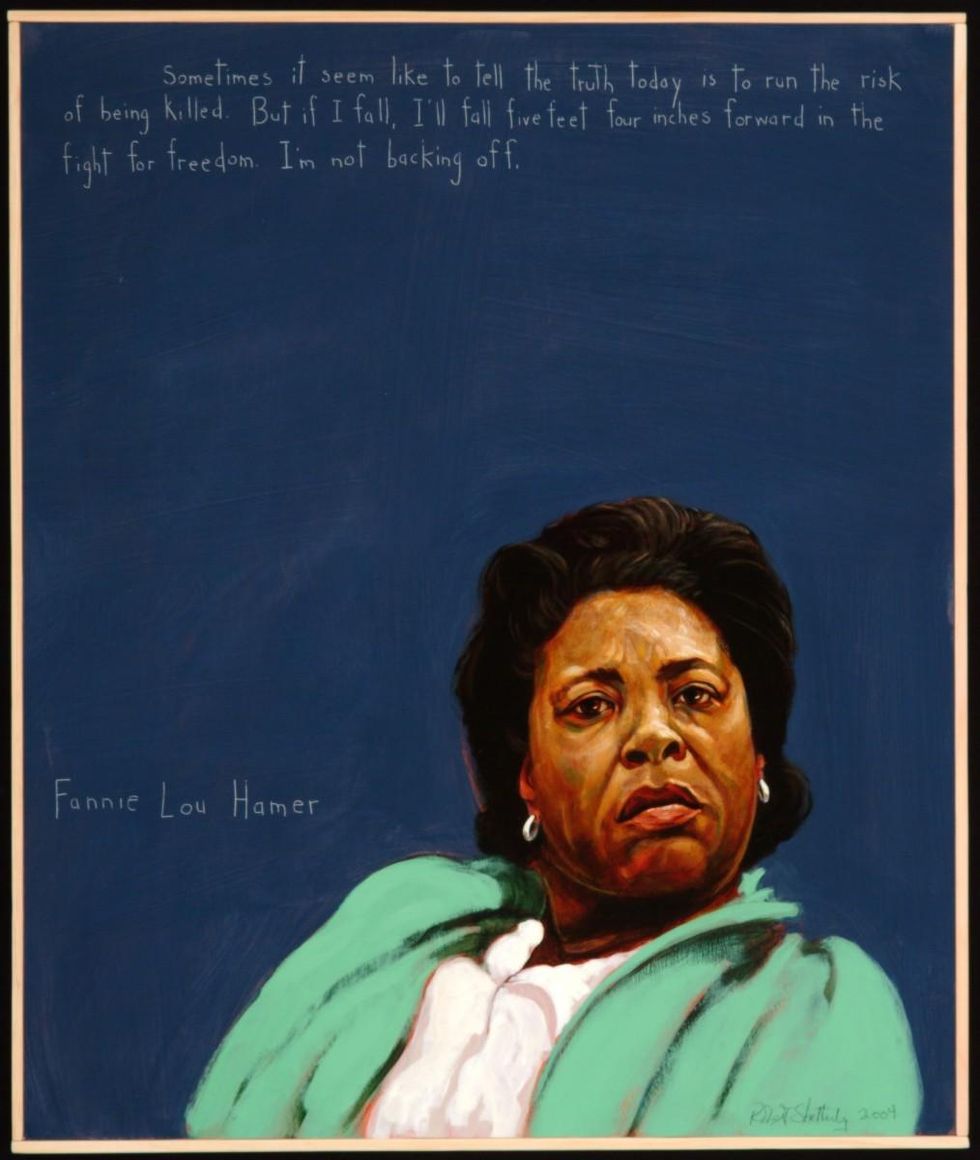

By choosing to display the portraits of Frederick Douglass, Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis, Monticello rejected Jefferson's notions of white supremacy. (Photo: Robert Shetterly)

When 75 Americans Who Tell the Truth portraits were shown at numerous locations around Charlottesville, Virginia, from January through April of this year, three of them, Frederick Douglass, John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer, were exhibited at Monticello, the celebrated home of Thomas Jefferson. The stately house and grounds, all designed by Jefferson, are exquisite. The rooms of the building are high-ceilinged but not large and the house is far less ostentatious than a contemporary McMansion. From the top of the mountain, the views in every direction are breathtaking, or, more accurately, commanding. These days, though, guides at Monticello are not protective of this commanding Founding Father's mythic status. They have no qualms about relating Jefferson's moral and human flaws, his political and philosophical contradictions, and how complicated it can be to assess his legacy. And I discovered that, as we try to assess Jefferson, we have to assess ourselves.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

As a political and revolutionary philosopher Thomas Jefferson crafted some of the world's greatest language declaring the moral necessity of democracy and individual rights and the inherently endowed equality of all people. The language persists because it gives voice to the truth of all human aspiration. If "these truths" are not true, then there is nothing wrong with constructing societies based on dictatorial hierarchies of power, wealth, racial supremacy and violent repression. People in countries all over the world have risked their lives for freedom, while finding their courage in Jefferson's words, believing they are "...endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." For those struggling to be free, the language itself has been as constant as the North Star for Harriet Tubman.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

And yet... Jefferson did not free his own slaves. This is why his story and its legacy become complicated in our history. Ask any middle school student, "What do we call a person who says one thing but does another?" Young students may not know many big words, but they know hypocrite. Jefferson's words are true, but his actions are, too.

So what do we do with that? Ignore it, as was done for two hundred years? Excuse it: He was a product of his time! Washington and Madison didn't free their slaves either. Oh, for god's sake he was perhaps the greatest of the Founding Fathers - cut him some slack! Should we knock him off his pedestal as ruthlessly as we yank Robert E. Lee from his horse? Wasn't General Lee fighting to preserve the system of human bondage Jefferson couldn't forsake? We are all taught to judge people by their actions, not by their words. So, if we judge Jefferson's actions, what becomes of his words? Are they empty vessels?

The grace with which Jefferson expressed his creative genius - mirrored in his house, his grounds, his lifestyle, the architecture of his sentences - was a stolen luxury, exceeding his economic means. Over the course of his lifetime, he owned more than 600 slaves who were ordered without pay to level the top of a mountain, build his mansion, tend his beautiful gardens, cook his meals and the meals of his many guests, cut his wood, satisfy his sexual desires (Jefferson was 44 years old and Sally Hemings, his property, was 14 when he first sexually abused her). The slaves' lives were thwarted, curtailed, used up, expended, exploited, stolen for whatever their owner demanded. And still he was in debt.

On the visible side of his balance sheet was the fact that slaves were his primary asset, his means of having credit extended, the wealth he would leave for his children. On the unseen side was immense grief, an accumulation of suffering and despair which could never be counted up or measured, would never be accounted for. His slaves' anguish provided his contentment, the visible trappings of his prestige. The slaves were his capital; they constituted his financial salvation. One could say, with a cruel and perverse twist, that slaves bought Jefferson's freedom. So, Jefferson's words are the fire which warms our hearts, his actions the fire which burns down the house. If this man can't live up to the truth of his own ideals, who can? He's taking the great leap forward but landing with his boots still mired in the status quo.

Jefferson fully understood the contradiction between his political language and his failure to free his slaves. He explained it partly in racist terms. Blacks, he said, were not the intellectual equals of whites. Nonetheless, he admitted that slavery was a moral abomination. In fact, he said it was so awful that, once freed, blacks would never forgive whites and would seek vengeance. For that reason, freed slaves would have to be resettled in a separate country. Isn't that a startling admission? Slave owning whites could - should - forever evade their guilt by exiling the rightful agents of just retribution.

I think, though, that the racial issues were not as determinative as the economic. Jefferson's ideals were balanced against his 'interests,' his economic stability, his prestige and personal power, his freedom to express himself. The slaves allowed him to express his talents on a grand scale, his architectural creativity transforming his ideas into reality. But his moral grandeur deflated in the presence of economic insecurity. I use the term 'interests' in precisely the way the U.S. government uses the term American Interests to justify alliances with brutal and corrupt despots, promote wars to control essential resources, destroy unique environments in order to build military bases or reap profit, enforce murderous sanctions, help defeat the struggles of people fighting for self-determination - everything that is the opposite of our stated ideals. We are told that our lifestyle depends on such contradictory behavior, and we accept it, just as Jefferson did. Because we put the word 'American' in front of the word 'Interests,' it's OK. More than OK; it's patriotic. Our economic necessity becomes the unstated ideal. American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

When looked at this way, we should not be too quick to judge Jefferson for abandoning his ideals. American foreign policy negotiates the world with pretty much the same dualities; our interests and our appetites relentlessly petition us to forgive ourselves our hypocrisies.

When the life and ideas of Jefferson are taught in our schools, though, far more attention is paid to his ideas than to his compromises. Those ideas are presented as the keystone of the arch through which we should enter the sacred history of American Democracy. Kind of like the arch we pass through into Disney World. As we walk into Disney World, we agree to suspend disbelief. That's what makes it magical: that man dressed up like Mickey Mouse is Mickey Mouse. What would be the fun of thinking otherwise? Similarly, when we study American history, strolling in under the arch of Jeffersonian ideals, we are greeted by Uncle Sam, our mascot of freedom, of American Exceptionalism and self-congratulatory destiny. There's nothing wrong with Uncle Sam touting the ideals. He should. The problem comes when he wears the mask of the ideals to hide the uncomfortable realities.

Jefferson's interests set the keystone to another arch. That version of history is entered by accepting the primacy of the interests of the powerful (wealthy individuals, politicians, corporations) and abandoning our ideals in favor of self-interest, even if that means great inequality and suffering for other people and species. This is called realpolitik: The world is a tough place. If your power doesn't take what it wants, someone else's will. Suffering caused by the projection of power is just the way it goes, always has been, always will be. America's Empire is not built on democracy; it's built on power.

Both arches exist. The arch of ideals can exist only where justice, equality and truth flourish. The second only where power and profit are given priority over ideals. The latter one leads to injustice, inequality and propaganda as the price of doing business. In the face of power, ideals can seem naive and quaint, necessarily irrelevant to people making real world decisions.

But, of course, the ideals are anything but naive, quaint and powerless. By choosing to display the portraits of Frederick Douglass, Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis, Monticello rejected Jefferson's notions of white supremacy. They chose, instead, to exhibit people who used his word to fight against the legacy of his actions. Their non-violent militancy outflanked the callousness of racism and profit taking. Institutionalized power does not inspire love and courage. It inspires fear. But if we refuse to shrink in the face of fear, we also reject the need to forsake truth, the dream of equality, real democracy and dignity for all people.

Douglass, Hamer and Lewis worked to rescue America from its flaws, Jefferson's flaws, while at the same time appealing to Jeffersonian ideals as their source of determination and justification. Each was horribly victimized by this country but did not, as Jefferson envisioned, seek revenge. Instead they embraced their oppressor in the spirit of love and justice, the spirit of a more perfect union. They wanted to heal their oppressor, not destroy him. They improved the quality of their suffering by choosing that healing.

It's painful to speculate how different our history might have been, the altered quotient of human suffering in this country, and the world, if Jefferson, Washington and Madison had freed their slaves.

Jefferson was not a saint. Unfortunately, his flaws have a legacy equal to his ideals. The number of the victims and the immensity of suffering caused by those flaws are immeasurable. The genius of his political philosophy was that it was moral, so his moral flaws cut deep.

The silver lining of the coronavirus pandemic is that it is exposing injustices in our economic, energy, and health systems. As the world pauses and prepares to reset, each of us is being given another chance to choose our ideals over our interests. Those ideals are in the long-term interest of a sustainable and just world. Thomas Jefferson would be grateful to finally find his words and actions in accord.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When 75 Americans Who Tell the Truth portraits were shown at numerous locations around Charlottesville, Virginia, from January through April of this year, three of them, Frederick Douglass, John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer, were exhibited at Monticello, the celebrated home of Thomas Jefferson. The stately house and grounds, all designed by Jefferson, are exquisite. The rooms of the building are high-ceilinged but not large and the house is far less ostentatious than a contemporary McMansion. From the top of the mountain, the views in every direction are breathtaking, or, more accurately, commanding. These days, though, guides at Monticello are not protective of this commanding Founding Father's mythic status. They have no qualms about relating Jefferson's moral and human flaws, his political and philosophical contradictions, and how complicated it can be to assess his legacy. And I discovered that, as we try to assess Jefferson, we have to assess ourselves.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

As a political and revolutionary philosopher Thomas Jefferson crafted some of the world's greatest language declaring the moral necessity of democracy and individual rights and the inherently endowed equality of all people. The language persists because it gives voice to the truth of all human aspiration. If "these truths" are not true, then there is nothing wrong with constructing societies based on dictatorial hierarchies of power, wealth, racial supremacy and violent repression. People in countries all over the world have risked their lives for freedom, while finding their courage in Jefferson's words, believing they are "...endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." For those struggling to be free, the language itself has been as constant as the North Star for Harriet Tubman.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

And yet... Jefferson did not free his own slaves. This is why his story and its legacy become complicated in our history. Ask any middle school student, "What do we call a person who says one thing but does another?" Young students may not know many big words, but they know hypocrite. Jefferson's words are true, but his actions are, too.

So what do we do with that? Ignore it, as was done for two hundred years? Excuse it: He was a product of his time! Washington and Madison didn't free their slaves either. Oh, for god's sake he was perhaps the greatest of the Founding Fathers - cut him some slack! Should we knock him off his pedestal as ruthlessly as we yank Robert E. Lee from his horse? Wasn't General Lee fighting to preserve the system of human bondage Jefferson couldn't forsake? We are all taught to judge people by their actions, not by their words. So, if we judge Jefferson's actions, what becomes of his words? Are they empty vessels?

The grace with which Jefferson expressed his creative genius - mirrored in his house, his grounds, his lifestyle, the architecture of his sentences - was a stolen luxury, exceeding his economic means. Over the course of his lifetime, he owned more than 600 slaves who were ordered without pay to level the top of a mountain, build his mansion, tend his beautiful gardens, cook his meals and the meals of his many guests, cut his wood, satisfy his sexual desires (Jefferson was 44 years old and Sally Hemings, his property, was 14 when he first sexually abused her). The slaves' lives were thwarted, curtailed, used up, expended, exploited, stolen for whatever their owner demanded. And still he was in debt.

On the visible side of his balance sheet was the fact that slaves were his primary asset, his means of having credit extended, the wealth he would leave for his children. On the unseen side was immense grief, an accumulation of suffering and despair which could never be counted up or measured, would never be accounted for. His slaves' anguish provided his contentment, the visible trappings of his prestige. The slaves were his capital; they constituted his financial salvation. One could say, with a cruel and perverse twist, that slaves bought Jefferson's freedom. So, Jefferson's words are the fire which warms our hearts, his actions the fire which burns down the house. If this man can't live up to the truth of his own ideals, who can? He's taking the great leap forward but landing with his boots still mired in the status quo.

Jefferson fully understood the contradiction between his political language and his failure to free his slaves. He explained it partly in racist terms. Blacks, he said, were not the intellectual equals of whites. Nonetheless, he admitted that slavery was a moral abomination. In fact, he said it was so awful that, once freed, blacks would never forgive whites and would seek vengeance. For that reason, freed slaves would have to be resettled in a separate country. Isn't that a startling admission? Slave owning whites could - should - forever evade their guilt by exiling the rightful agents of just retribution.

I think, though, that the racial issues were not as determinative as the economic. Jefferson's ideals were balanced against his 'interests,' his economic stability, his prestige and personal power, his freedom to express himself. The slaves allowed him to express his talents on a grand scale, his architectural creativity transforming his ideas into reality. But his moral grandeur deflated in the presence of economic insecurity. I use the term 'interests' in precisely the way the U.S. government uses the term American Interests to justify alliances with brutal and corrupt despots, promote wars to control essential resources, destroy unique environments in order to build military bases or reap profit, enforce murderous sanctions, help defeat the struggles of people fighting for self-determination - everything that is the opposite of our stated ideals. We are told that our lifestyle depends on such contradictory behavior, and we accept it, just as Jefferson did. Because we put the word 'American' in front of the word 'Interests,' it's OK. More than OK; it's patriotic. Our economic necessity becomes the unstated ideal. American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

When looked at this way, we should not be too quick to judge Jefferson for abandoning his ideals. American foreign policy negotiates the world with pretty much the same dualities; our interests and our appetites relentlessly petition us to forgive ourselves our hypocrisies.

When the life and ideas of Jefferson are taught in our schools, though, far more attention is paid to his ideas than to his compromises. Those ideas are presented as the keystone of the arch through which we should enter the sacred history of American Democracy. Kind of like the arch we pass through into Disney World. As we walk into Disney World, we agree to suspend disbelief. That's what makes it magical: that man dressed up like Mickey Mouse is Mickey Mouse. What would be the fun of thinking otherwise? Similarly, when we study American history, strolling in under the arch of Jeffersonian ideals, we are greeted by Uncle Sam, our mascot of freedom, of American Exceptionalism and self-congratulatory destiny. There's nothing wrong with Uncle Sam touting the ideals. He should. The problem comes when he wears the mask of the ideals to hide the uncomfortable realities.

Jefferson's interests set the keystone to another arch. That version of history is entered by accepting the primacy of the interests of the powerful (wealthy individuals, politicians, corporations) and abandoning our ideals in favor of self-interest, even if that means great inequality and suffering for other people and species. This is called realpolitik: The world is a tough place. If your power doesn't take what it wants, someone else's will. Suffering caused by the projection of power is just the way it goes, always has been, always will be. America's Empire is not built on democracy; it's built on power.

Both arches exist. The arch of ideals can exist only where justice, equality and truth flourish. The second only where power and profit are given priority over ideals. The latter one leads to injustice, inequality and propaganda as the price of doing business. In the face of power, ideals can seem naive and quaint, necessarily irrelevant to people making real world decisions.

But, of course, the ideals are anything but naive, quaint and powerless. By choosing to display the portraits of Frederick Douglass, Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis, Monticello rejected Jefferson's notions of white supremacy. They chose, instead, to exhibit people who used his word to fight against the legacy of his actions. Their non-violent militancy outflanked the callousness of racism and profit taking. Institutionalized power does not inspire love and courage. It inspires fear. But if we refuse to shrink in the face of fear, we also reject the need to forsake truth, the dream of equality, real democracy and dignity for all people.

Douglass, Hamer and Lewis worked to rescue America from its flaws, Jefferson's flaws, while at the same time appealing to Jeffersonian ideals as their source of determination and justification. Each was horribly victimized by this country but did not, as Jefferson envisioned, seek revenge. Instead they embraced their oppressor in the spirit of love and justice, the spirit of a more perfect union. They wanted to heal their oppressor, not destroy him. They improved the quality of their suffering by choosing that healing.

It's painful to speculate how different our history might have been, the altered quotient of human suffering in this country, and the world, if Jefferson, Washington and Madison had freed their slaves.

Jefferson was not a saint. Unfortunately, his flaws have a legacy equal to his ideals. The number of the victims and the immensity of suffering caused by those flaws are immeasurable. The genius of his political philosophy was that it was moral, so his moral flaws cut deep.

The silver lining of the coronavirus pandemic is that it is exposing injustices in our economic, energy, and health systems. As the world pauses and prepares to reset, each of us is being given another chance to choose our ideals over our interests. Those ideals are in the long-term interest of a sustainable and just world. Thomas Jefferson would be grateful to finally find his words and actions in accord.

When 75 Americans Who Tell the Truth portraits were shown at numerous locations around Charlottesville, Virginia, from January through April of this year, three of them, Frederick Douglass, John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer, were exhibited at Monticello, the celebrated home of Thomas Jefferson. The stately house and grounds, all designed by Jefferson, are exquisite. The rooms of the building are high-ceilinged but not large and the house is far less ostentatious than a contemporary McMansion. From the top of the mountain, the views in every direction are breathtaking, or, more accurately, commanding. These days, though, guides at Monticello are not protective of this commanding Founding Father's mythic status. They have no qualms about relating Jefferson's moral and human flaws, his political and philosophical contradictions, and how complicated it can be to assess his legacy. And I discovered that, as we try to assess Jefferson, we have to assess ourselves.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

As a political and revolutionary philosopher Thomas Jefferson crafted some of the world's greatest language declaring the moral necessity of democracy and individual rights and the inherently endowed equality of all people. The language persists because it gives voice to the truth of all human aspiration. If "these truths" are not true, then there is nothing wrong with constructing societies based on dictatorial hierarchies of power, wealth, racial supremacy and violent repression. People in countries all over the world have risked their lives for freedom, while finding their courage in Jefferson's words, believing they are "...endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights." For those struggling to be free, the language itself has been as constant as the North Star for Harriet Tubman.

American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

And yet... Jefferson did not free his own slaves. This is why his story and its legacy become complicated in our history. Ask any middle school student, "What do we call a person who says one thing but does another?" Young students may not know many big words, but they know hypocrite. Jefferson's words are true, but his actions are, too.

So what do we do with that? Ignore it, as was done for two hundred years? Excuse it: He was a product of his time! Washington and Madison didn't free their slaves either. Oh, for god's sake he was perhaps the greatest of the Founding Fathers - cut him some slack! Should we knock him off his pedestal as ruthlessly as we yank Robert E. Lee from his horse? Wasn't General Lee fighting to preserve the system of human bondage Jefferson couldn't forsake? We are all taught to judge people by their actions, not by their words. So, if we judge Jefferson's actions, what becomes of his words? Are they empty vessels?

The grace with which Jefferson expressed his creative genius - mirrored in his house, his grounds, his lifestyle, the architecture of his sentences - was a stolen luxury, exceeding his economic means. Over the course of his lifetime, he owned more than 600 slaves who were ordered without pay to level the top of a mountain, build his mansion, tend his beautiful gardens, cook his meals and the meals of his many guests, cut his wood, satisfy his sexual desires (Jefferson was 44 years old and Sally Hemings, his property, was 14 when he first sexually abused her). The slaves' lives were thwarted, curtailed, used up, expended, exploited, stolen for whatever their owner demanded. And still he was in debt.

On the visible side of his balance sheet was the fact that slaves were his primary asset, his means of having credit extended, the wealth he would leave for his children. On the unseen side was immense grief, an accumulation of suffering and despair which could never be counted up or measured, would never be accounted for. His slaves' anguish provided his contentment, the visible trappings of his prestige. The slaves were his capital; they constituted his financial salvation. One could say, with a cruel and perverse twist, that slaves bought Jefferson's freedom. So, Jefferson's words are the fire which warms our hearts, his actions the fire which burns down the house. If this man can't live up to the truth of his own ideals, who can? He's taking the great leap forward but landing with his boots still mired in the status quo.

Jefferson fully understood the contradiction between his political language and his failure to free his slaves. He explained it partly in racist terms. Blacks, he said, were not the intellectual equals of whites. Nonetheless, he admitted that slavery was a moral abomination. In fact, he said it was so awful that, once freed, blacks would never forgive whites and would seek vengeance. For that reason, freed slaves would have to be resettled in a separate country. Isn't that a startling admission? Slave owning whites could - should - forever evade their guilt by exiling the rightful agents of just retribution.

I think, though, that the racial issues were not as determinative as the economic. Jefferson's ideals were balanced against his 'interests,' his economic stability, his prestige and personal power, his freedom to express himself. The slaves allowed him to express his talents on a grand scale, his architectural creativity transforming his ideas into reality. But his moral grandeur deflated in the presence of economic insecurity. I use the term 'interests' in precisely the way the U.S. government uses the term American Interests to justify alliances with brutal and corrupt despots, promote wars to control essential resources, destroy unique environments in order to build military bases or reap profit, enforce murderous sanctions, help defeat the struggles of people fighting for self-determination - everything that is the opposite of our stated ideals. We are told that our lifestyle depends on such contradictory behavior, and we accept it, just as Jefferson did. Because we put the word 'American' in front of the word 'Interests,' it's OK. More than OK; it's patriotic. Our economic necessity becomes the unstated ideal. American Interests becomes too often a euphemism for crimes against humanity, racism, anti-democratic movements. We use the term American Interests to betray Jefferson's ideals, just as he did.

When looked at this way, we should not be too quick to judge Jefferson for abandoning his ideals. American foreign policy negotiates the world with pretty much the same dualities; our interests and our appetites relentlessly petition us to forgive ourselves our hypocrisies.

When the life and ideas of Jefferson are taught in our schools, though, far more attention is paid to his ideas than to his compromises. Those ideas are presented as the keystone of the arch through which we should enter the sacred history of American Democracy. Kind of like the arch we pass through into Disney World. As we walk into Disney World, we agree to suspend disbelief. That's what makes it magical: that man dressed up like Mickey Mouse is Mickey Mouse. What would be the fun of thinking otherwise? Similarly, when we study American history, strolling in under the arch of Jeffersonian ideals, we are greeted by Uncle Sam, our mascot of freedom, of American Exceptionalism and self-congratulatory destiny. There's nothing wrong with Uncle Sam touting the ideals. He should. The problem comes when he wears the mask of the ideals to hide the uncomfortable realities.

Jefferson's interests set the keystone to another arch. That version of history is entered by accepting the primacy of the interests of the powerful (wealthy individuals, politicians, corporations) and abandoning our ideals in favor of self-interest, even if that means great inequality and suffering for other people and species. This is called realpolitik: The world is a tough place. If your power doesn't take what it wants, someone else's will. Suffering caused by the projection of power is just the way it goes, always has been, always will be. America's Empire is not built on democracy; it's built on power.

Both arches exist. The arch of ideals can exist only where justice, equality and truth flourish. The second only where power and profit are given priority over ideals. The latter one leads to injustice, inequality and propaganda as the price of doing business. In the face of power, ideals can seem naive and quaint, necessarily irrelevant to people making real world decisions.

But, of course, the ideals are anything but naive, quaint and powerless. By choosing to display the portraits of Frederick Douglass, Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis, Monticello rejected Jefferson's notions of white supremacy. They chose, instead, to exhibit people who used his word to fight against the legacy of his actions. Their non-violent militancy outflanked the callousness of racism and profit taking. Institutionalized power does not inspire love and courage. It inspires fear. But if we refuse to shrink in the face of fear, we also reject the need to forsake truth, the dream of equality, real democracy and dignity for all people.

Douglass, Hamer and Lewis worked to rescue America from its flaws, Jefferson's flaws, while at the same time appealing to Jeffersonian ideals as their source of determination and justification. Each was horribly victimized by this country but did not, as Jefferson envisioned, seek revenge. Instead they embraced their oppressor in the spirit of love and justice, the spirit of a more perfect union. They wanted to heal their oppressor, not destroy him. They improved the quality of their suffering by choosing that healing.

It's painful to speculate how different our history might have been, the altered quotient of human suffering in this country, and the world, if Jefferson, Washington and Madison had freed their slaves.

Jefferson was not a saint. Unfortunately, his flaws have a legacy equal to his ideals. The number of the victims and the immensity of suffering caused by those flaws are immeasurable. The genius of his political philosophy was that it was moral, so his moral flaws cut deep.

The silver lining of the coronavirus pandemic is that it is exposing injustices in our economic, energy, and health systems. As the world pauses and prepares to reset, each of us is being given another chance to choose our ideals over our interests. Those ideals are in the long-term interest of a sustainable and just world. Thomas Jefferson would be grateful to finally find his words and actions in accord.