We are five Americans living in social democratic Norway. We think that our experiences provide a unique perspective as to why it is that so many Americans so strongly support the reforms called for by the platform of Sen. Bernie Sanders. Our time in Norway also helps to explain why it is so challenging for many Americans to imagine Sanders' proposals in concrete terms. We draw from our dual reality of living in Norway while looking over--with critical eyes--at what's going on in the United States.

"As Americans living in Norway, we have profoundly experienced what policies like universal health care, parental leave, free higher education, the right to vacation and sick pay mean for our lives. To experience the everyday effect of these policies has strengthened our political convictions."

The five of us moved from all corners of the U.S .to Norway, for different reasons. Despite these differences, we've all come to the conclusion that the Sanders campaign provides necessary answers to challenges that the U.S. faces. The five of us are constantly reminded of the many ways in which our lives in Norway stand in stark contrast to the lives of our friends and family back home. Americans often explain their political choices by drawing on concrete life experiences--it's also the same with us. Notably, the years we've lived in Norway have provided us with visceral proof of the type of society it's possible to create together and the time it may take for these possibilities to feel real.

Everyday social democracy: Three stories

Erika: "When I lived in the U.S., I was deeply engaged in movements for universal healthcare, and for workers and women's rights. Nonetheless, I didn't truly understand the impact of the rights I was championing until I first moved to Norway. When I arrived, I was five months pregnant with my first child and I was excited about the prospect of a new life in a land with generous public provisions. At the same time, I was scared and unsure, mostly because I couldn't fathom a system where I could be seen by a doctor, right way, without significant paperwork or cost to me or my partner. With my first pregnancy check-up in Norway a week after arrival, I experienced firsthand my new reality. It felt strange and incredible to have access to these services, with no questions asked.

I had a difficult childbirth and was completely exhausted for several weeks after my son was born. At the time, I was enrolled in a demanding master's program, for free! My twin sister, living in the US, gave birth to twin daughters in that same time period. She had felt the pressure to begin to work again almost right away and based on everything I knew, it never occurred to me that I shouldn't do the same. I took 10 days off after the birth and slogged my way through the snow to go to my classes, leaving my son's Norwegian father to use his parental leave and stay home with our son. I remember feeling proud of my strong work ethic when I completed my studies, but also feeling exhausted--both mentally and emotionally.

Two years later, I gave birth to my second child. In the years that had passed since the first, I'd continually seen Norwegian friends and colleagues taking 8 months to a year's parental leave--paid leave from their jobs, from their studies, from all parts of life outside of caring for a newborn. This time, there was no doubt in my mind that I would do the same. With a huge feeling of relief, I took the weeks I needed before the birth and I took the months after. Although my politics had been far to the left when I lived in the US, it was only first after I'd lived some years in Norway that I actually felt I deserved to receive universal health care and paid parental leave. It was only then that I understood the everyday, emotional impact of what it was to have that right."

Jen: "In recent years, I have been genuinely surprised upon learning that neither my sister nor my cousin, despite both having higher degrees and full-time positions, were not receiving paid vacation or sick leave from work. This past Christmas, my uncle, past age 70 and in poor health, left me equally thrown when he told me he wasn't retiring because he 'simply couldn't afford to'. And yet, well beyond hearing these everyday realities, the thing that surprises me most is my family members responding to my shock with mild amusement and telling me that I've simply 'been in Norway too long.'

Are they right? Have I been in Norway so long that I no longer understand the everyday realities of the American worker? When did it happen that I could no longer imagine the type of work life they talk about? I've always had a good work ethic and I've understood that you have to work hard to earn money. But after so many years in Norway, the lack of work/life balance in the U.S. experience has started to feel almost inhumane.

This new personal understanding happened a few years ago, at a point when my husband and doctor became so worried about the pressure I felt from work that they convinced me to take a bit of time away. When they called it "sick leave" I remember feeling strongly that I didn't fit in this category. My experience from the U.S. had been that it was only those with serious illnesses or life problems who took sick leave. Nonetheless, they convinced me to take the break I so desperately needed. I was paid during my leave, so I did everything I could to make the most out of what felt like an undeserved opportunity. I went on hikes, I read and wrote, and I met regularly with my doctor and psychologist. I was away from work for two months and the experience changed my life. I felt healthier and more focused, both at work and in my personal life. It was the first time I understood the significance of Norwegian sick leave policies. Taking sick leave and taking stock is not a rare thing in Norway. The policy reflects a holistic view of what it means to work. It recognizes that when an employee's health isn't good, they are less effective during the work day. It's therefore a no-brainer that the employer meets the employee where they're at.

Tony: "I grew up in Vermont. I say that because Bernie Sanders has really formed the way I think, even if I haven't always been as conscious of this as I am now. But while I 'grew up with Bernie', it wasn't until I came to Norway that I fully understood the significance of the ideas he stands for. In the U.S., market liberalism is just what... is. As a Bachelor's student in Political Science at the University of Vermont, I was surrounded by this perspective. My goal was to have a good-paying career, even if I wasn't happy or interested in what I was doing. And I wasn't alone--many students in the U.S. struggle with this expectation.

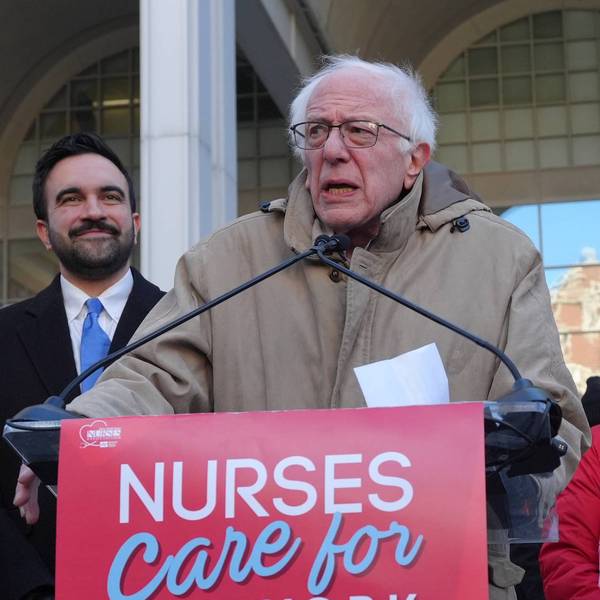

"Only Bernie Sanders has taken seriously the aim of building a more just, less brutal society--and this is reflected in the growth of the movement behind him. It's here that the power of the Sanders campaign lies--it speaks to regular people who want an easier everyday and a better chance to live good, secure lives."

I moved to Norway in fall 2016 because, with its free higher education, it was my only economically feasible chance of accessing a Master's degree in International Relations. In my first few years in Norway I was introduced to Marxist philosophy, which I had never seen in four years with my previous higher education. But even more important than new theoretical perspectives, was that despite the fact that I was living on a student budget in Norway, I nonetheless experienced a quality of life that was equivalent to my privileged peers in the U.S.--those who had much more money than me. It was a new and strange experience to not worry about each and every financial decision I made. I realized that there were a breadth of political realities around the world and that the one in the U.S. is rather...unique. My experiences in Norway convinced me to shift from being a completely normal American "liberal" to locating myself much further left, politically."

Grassroots social reform takes time

As Americans living in Norway, we have profoundly experienced what policies like universal health care, parental leave, free higher education, the right to vacation and sick pay mean for our lives. To experience the everyday effect of these policies has strengthened our political convictions. Of the Democratic candidates, only Bernie Sanders has taken seriously the aim of building a more just, less brutal society--and this is reflected in the growth of the movement behind him. It's here that the power of the Sanders campaign lies--it speaks to regular people who want an easier everyday and a better chance to live good, secure lives. Nonetheless, without everyday, real life experience with comprehensive state support, it is not difficult for us to imagine how these reforms feel like a move outside the comfort zone for many Americans. Such a shift requires more than a short lived electoral campaign. It's not coincidental that the Sanders campaign resembles more of a grassroots movement. For us, just as for many in the U.S. who are knocking on doors, phoning people they don't know and contributing in other ways, there's more at stake than winning a primary election against Joe Biden. It's about creating a broad movement of people who can create the sense that reform is both possible and results in a better way of life. From experience, we can say that the process takes time--but it's worth it.