SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

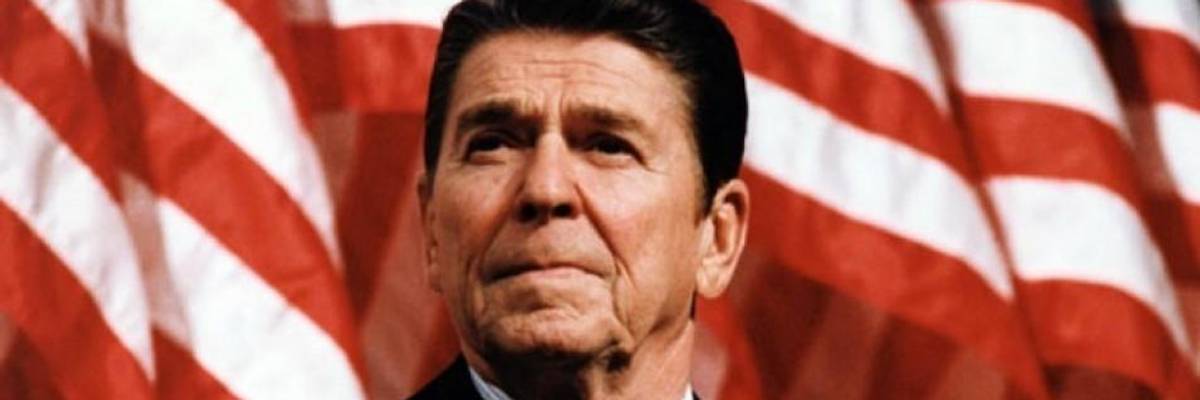

The crimes of Iran-Contra were shocking when they were revealed in real-time, but the murky ending has allowed the story to drift into relative obscurity, especially as the American right-wing embarked on a campaign (which I wrote a book about) to create a mythical Ronald Reagan who'd be worthy of a spot on Mt. Rushmore. (Photo: Marion Ross/flickr/cc)

When the scandal finally broke, it was on the other side of the Atlantic, in a nation that millions of Americans couldn't pinpoint on a map. Congress had made its intentions clear in the form of legislation, but the White House secretly ignored that to illegally pursue its own controversial agenda. Meanwhile, it was revealed that shady foreign-born middlemen were pocketing millions of dollars. The president's approval rating plummeted, and it looked like an early exit.

"I had hoped there would not be discovery of an impeachable offense," the Speaker of the House said at one point. "I didn't want to focus on such a divisive subject."

What's so interesting is that despite all the similarities between the Iran-Contra mess and President Trump's Ukraine affair, in which an American president used the immense clout of his office in a scheme to extort an election-interfering political favor from a foreign leader, it's a comparison that almost never gets made in today's 24/7 hotbox of cable TV news. America decided to forget Iran-Contra back in 1987. It's a pledge we're still keeping in 2019.

At the end of the tumultuous 1960s and '70s, the great Joan Didion wrote: "We tell ourselves stories in order to live ... We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices." In American politics, the most workable choice is Watergate, and it's been that way ever since Richard Nixon waved from the helicopter steps in 1974.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then--a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement--probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump.

Forty-five years later, as the world of punditry struggles to put the sprawling amorality of Donald Trump into a tidy box, TV producers raised in the dark shadows of Deep Throat continually invite the stars of Watergate -- John Dean, Woodward and Bernstein, Jill Wine-Banks -- into your living room to impose reason and order. And why not? The system worked, right? There were checks and balances, just like the Founding Fathers drew it up. The journalists, the judges, and Congress did their jobs and masses overwhelmingly approved.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then -- a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement -- probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump. It was a post-Watergate restoration of situational ethics over the rule of law, and a new understanding that impeachment was a political act in a time when raw partisanship was just beginning to trump (pun intended) principle.

The crimes of Iran-Contra were shocking when they were revealed in real-time, but the murky ending has allowed the story to drift into relative obscurity, especially as the American right-wing embarked on a campaign (which I wrote a book about) to create a mythical Ronald Reagan who'd be worthy of a spot on Mt. Rushmore. If you're one of the majority of folks born since 1970 (or spent 1987 grooving on Van Halen records instead of politics) here's a super-quick refresher.

Reagan, who seemed like the most conservative and reactionary president America could possibly have (yes, we were that naive), centered his foreign policy on fighting Communism and socialism around the globe. That included Central America, where a leftist, U.S.-opposed regime had taken control in Nicaragua. But Reagan's biggest headache proved to be terrorism in the Middle East, including a string of kidnappings of Americans in Lebanon.

You'd think one problem had little to do with the other. But the 40th president agonized over the hostages and was willing to take extreme, secret measures to free them. His team learned that Iran -- the former U.S.-ally-turned-enemy after 1979's Islamic revolution, now in a war with Iraq and desperately needing military aid -- had sway with the hijackers. That gave rise to a hidden network, using unsavory middlemen, of trading arms for hostages.

But the scheme generated extra profits, right at a time when Reagan's other big foreign-policy frustration was Congress balking at funds for his would-be allies in Central America, including a human-rights nightmare of a right-wing reactionary movement in Nicaragua called the Contras. In fact, during Reagan's first term, Congress barred aiding the Contras in a measure known as the Boland Amendment -- which Team Reagan decided to circumvent by steering the off-the-book profits from the Iranian arms deals to the Contras. It was a brazen, outrageous scheme that unraveled quickly when -- on October 5, 1986 -- an American pilot named Eugene Hasenfus flying some of that illicit aid to the Contras was shot down, captured, and confessed everything.

This massive breach of the public trust happened just a dozen years after the national trauma of Watergate. Objectively, it's hard not to see a throughline of high crimes and misdemeanors from Nixon's dirty tricks and cover-ups to both Iran-Contra and Trump's regime of wrongdoing that spiked with the Ukraine misadventure. Each involved a power-hungry president using illegal methods to trample their opposition -- whether on Capitol Hill or rivals for the presidency -- and then lying about it on massive scale. A former CIA officer named Felix Rodriguez tried to warn a key Iran-Contra figure that this "could be worse than Watergate and ... could destroy the president."

It didn't, though. Yes, there were nationally televised hearings in Congress, and an aggressive prosecutor who criminally charged a number of key Reagan aides and other players. But there was never any serious appetite for impeaching the Gipper. There was a perfect storm of reasons why. Reagan was always personally popular--despite moments when his political approval plunged -- and the fact that he was America's oldest president, coming off as disengaged, actually bolstered a sense that he was out-of-the-loop on the worst crimes. But Reagan had also been elected on an explicit promise to move America past the malaise of the 1970s, which had included Watergate. By 1987, many voters preferred ignorant triumphalism over the scold of accountability.

Even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism.

And even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism, as previously conservative Southern Democrats and northern liberal Republicans had by now mostly switched parties. Reagan was protected in Iran-Contra by a solid GOP wall led by a Wyoming Republican named Dick Cheney, who insisted "[t]here was no constitutional crisis, no systematic disrespect for 'the rule of law,' no grand conspiracy, and no Administration-wide dishonesty or cover up."

Cheney also was, and still is, a champion of the "unitary executive theory" which sees an American president holding almost-monarchical powers that must thwart efforts by Congress or the courts to interfere. Indeed, one reason why Iran-Contra ended with Reagan not only still in office but as the future icon of American conservatism was Republicans' willingness to openly embrace the exercise of power (unlike Nixon telling his aides to "stonewall" and cover-up) and wrap it in a cloth of patriotism. This was punctuated by the bravado of Lt. Col. Oliver North who gave swashbuckling testimony in full uniform, beat a criminal rap and became a hero of the right.

Some 32 years later, the square peg of Trump's impeachment won't fit into the round hole of Watergate, and maybe that's because the GOP is running the Iran-Contra playbook of massive resistance while hailing the idea of an all-powerful, literally unimpeachable chief executive (something no one desired in 1787). (I won't go off on a complicated tangent but there's also an argument that Bill Clinton's 1998 impeachment was a B-side to Iran-Contra, because in a very different way it cemented the same central premise -- that impeachment is partisan, ugly and not what the Founding Fathers would have wanted...even though it was what they wanted.)

None of this is a guarantee that Trump ends like Iran-Contra did. After all, Reagan was arguably one of the most-liked U.S. presidents while Trump is loathed even by some of those who vote for him. More importantly, the naked political greed of Trump's Ukraine scheme is arguably morally much worse than the more ideological crimes of the 1980s.

But let's be honest: The principles first laid bare in Iran-Contra -- a deference to the raw exercise of power, including a willingness to overlook the rule of law--have become America's cruel guiding spirit in the 21st century. On TV, Watergate -- with its quaint mantra of checks and balances and its moral that "the system worked" -- remains the story we tell ourselves to live, even as a Republican Senate prepares to snowplow that plot line in January.

And there's a depressing but fitting footnote to all of this. All of the major administration officials convicted of crimes in Iran-Contra -- former defense secretary Caspar Weinberger, and five others--were pardoned by outgoing President George H.W. Bush (he'd been Reagan's VP) on Christmas Eve, 1992. The move -- which ensured no one would be held accountable for one of the worst scandals in U.S. history--had gotten an OK from Bush 41's attorney general, a man whose belief in a unitary chief executive with quasi-dictatorial powers has only grown in the years since then. The attorney general then is the attorney general now: William Barr.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When the scandal finally broke, it was on the other side of the Atlantic, in a nation that millions of Americans couldn't pinpoint on a map. Congress had made its intentions clear in the form of legislation, but the White House secretly ignored that to illegally pursue its own controversial agenda. Meanwhile, it was revealed that shady foreign-born middlemen were pocketing millions of dollars. The president's approval rating plummeted, and it looked like an early exit.

"I had hoped there would not be discovery of an impeachable offense," the Speaker of the House said at one point. "I didn't want to focus on such a divisive subject."

What's so interesting is that despite all the similarities between the Iran-Contra mess and President Trump's Ukraine affair, in which an American president used the immense clout of his office in a scheme to extort an election-interfering political favor from a foreign leader, it's a comparison that almost never gets made in today's 24/7 hotbox of cable TV news. America decided to forget Iran-Contra back in 1987. It's a pledge we're still keeping in 2019.

At the end of the tumultuous 1960s and '70s, the great Joan Didion wrote: "We tell ourselves stories in order to live ... We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices." In American politics, the most workable choice is Watergate, and it's been that way ever since Richard Nixon waved from the helicopter steps in 1974.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then--a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement--probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump.

Forty-five years later, as the world of punditry struggles to put the sprawling amorality of Donald Trump into a tidy box, TV producers raised in the dark shadows of Deep Throat continually invite the stars of Watergate -- John Dean, Woodward and Bernstein, Jill Wine-Banks -- into your living room to impose reason and order. And why not? The system worked, right? There were checks and balances, just like the Founding Fathers drew it up. The journalists, the judges, and Congress did their jobs and masses overwhelmingly approved.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then -- a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement -- probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump. It was a post-Watergate restoration of situational ethics over the rule of law, and a new understanding that impeachment was a political act in a time when raw partisanship was just beginning to trump (pun intended) principle.

The crimes of Iran-Contra were shocking when they were revealed in real-time, but the murky ending has allowed the story to drift into relative obscurity, especially as the American right-wing embarked on a campaign (which I wrote a book about) to create a mythical Ronald Reagan who'd be worthy of a spot on Mt. Rushmore. If you're one of the majority of folks born since 1970 (or spent 1987 grooving on Van Halen records instead of politics) here's a super-quick refresher.

Reagan, who seemed like the most conservative and reactionary president America could possibly have (yes, we were that naive), centered his foreign policy on fighting Communism and socialism around the globe. That included Central America, where a leftist, U.S.-opposed regime had taken control in Nicaragua. But Reagan's biggest headache proved to be terrorism in the Middle East, including a string of kidnappings of Americans in Lebanon.

You'd think one problem had little to do with the other. But the 40th president agonized over the hostages and was willing to take extreme, secret measures to free them. His team learned that Iran -- the former U.S.-ally-turned-enemy after 1979's Islamic revolution, now in a war with Iraq and desperately needing military aid -- had sway with the hijackers. That gave rise to a hidden network, using unsavory middlemen, of trading arms for hostages.

But the scheme generated extra profits, right at a time when Reagan's other big foreign-policy frustration was Congress balking at funds for his would-be allies in Central America, including a human-rights nightmare of a right-wing reactionary movement in Nicaragua called the Contras. In fact, during Reagan's first term, Congress barred aiding the Contras in a measure known as the Boland Amendment -- which Team Reagan decided to circumvent by steering the off-the-book profits from the Iranian arms deals to the Contras. It was a brazen, outrageous scheme that unraveled quickly when -- on October 5, 1986 -- an American pilot named Eugene Hasenfus flying some of that illicit aid to the Contras was shot down, captured, and confessed everything.

This massive breach of the public trust happened just a dozen years after the national trauma of Watergate. Objectively, it's hard not to see a throughline of high crimes and misdemeanors from Nixon's dirty tricks and cover-ups to both Iran-Contra and Trump's regime of wrongdoing that spiked with the Ukraine misadventure. Each involved a power-hungry president using illegal methods to trample their opposition -- whether on Capitol Hill or rivals for the presidency -- and then lying about it on massive scale. A former CIA officer named Felix Rodriguez tried to warn a key Iran-Contra figure that this "could be worse than Watergate and ... could destroy the president."

It didn't, though. Yes, there were nationally televised hearings in Congress, and an aggressive prosecutor who criminally charged a number of key Reagan aides and other players. But there was never any serious appetite for impeaching the Gipper. There was a perfect storm of reasons why. Reagan was always personally popular--despite moments when his political approval plunged -- and the fact that he was America's oldest president, coming off as disengaged, actually bolstered a sense that he was out-of-the-loop on the worst crimes. But Reagan had also been elected on an explicit promise to move America past the malaise of the 1970s, which had included Watergate. By 1987, many voters preferred ignorant triumphalism over the scold of accountability.

Even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism.

And even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism, as previously conservative Southern Democrats and northern liberal Republicans had by now mostly switched parties. Reagan was protected in Iran-Contra by a solid GOP wall led by a Wyoming Republican named Dick Cheney, who insisted "[t]here was no constitutional crisis, no systematic disrespect for 'the rule of law,' no grand conspiracy, and no Administration-wide dishonesty or cover up."

Cheney also was, and still is, a champion of the "unitary executive theory" which sees an American president holding almost-monarchical powers that must thwart efforts by Congress or the courts to interfere. Indeed, one reason why Iran-Contra ended with Reagan not only still in office but as the future icon of American conservatism was Republicans' willingness to openly embrace the exercise of power (unlike Nixon telling his aides to "stonewall" and cover-up) and wrap it in a cloth of patriotism. This was punctuated by the bravado of Lt. Col. Oliver North who gave swashbuckling testimony in full uniform, beat a criminal rap and became a hero of the right.

Some 32 years later, the square peg of Trump's impeachment won't fit into the round hole of Watergate, and maybe that's because the GOP is running the Iran-Contra playbook of massive resistance while hailing the idea of an all-powerful, literally unimpeachable chief executive (something no one desired in 1787). (I won't go off on a complicated tangent but there's also an argument that Bill Clinton's 1998 impeachment was a B-side to Iran-Contra, because in a very different way it cemented the same central premise -- that impeachment is partisan, ugly and not what the Founding Fathers would have wanted...even though it was what they wanted.)

None of this is a guarantee that Trump ends like Iran-Contra did. After all, Reagan was arguably one of the most-liked U.S. presidents while Trump is loathed even by some of those who vote for him. More importantly, the naked political greed of Trump's Ukraine scheme is arguably morally much worse than the more ideological crimes of the 1980s.

But let's be honest: The principles first laid bare in Iran-Contra -- a deference to the raw exercise of power, including a willingness to overlook the rule of law--have become America's cruel guiding spirit in the 21st century. On TV, Watergate -- with its quaint mantra of checks and balances and its moral that "the system worked" -- remains the story we tell ourselves to live, even as a Republican Senate prepares to snowplow that plot line in January.

And there's a depressing but fitting footnote to all of this. All of the major administration officials convicted of crimes in Iran-Contra -- former defense secretary Caspar Weinberger, and five others--were pardoned by outgoing President George H.W. Bush (he'd been Reagan's VP) on Christmas Eve, 1992. The move -- which ensured no one would be held accountable for one of the worst scandals in U.S. history--had gotten an OK from Bush 41's attorney general, a man whose belief in a unitary chief executive with quasi-dictatorial powers has only grown in the years since then. The attorney general then is the attorney general now: William Barr.

When the scandal finally broke, it was on the other side of the Atlantic, in a nation that millions of Americans couldn't pinpoint on a map. Congress had made its intentions clear in the form of legislation, but the White House secretly ignored that to illegally pursue its own controversial agenda. Meanwhile, it was revealed that shady foreign-born middlemen were pocketing millions of dollars. The president's approval rating plummeted, and it looked like an early exit.

"I had hoped there would not be discovery of an impeachable offense," the Speaker of the House said at one point. "I didn't want to focus on such a divisive subject."

What's so interesting is that despite all the similarities between the Iran-Contra mess and President Trump's Ukraine affair, in which an American president used the immense clout of his office in a scheme to extort an election-interfering political favor from a foreign leader, it's a comparison that almost never gets made in today's 24/7 hotbox of cable TV news. America decided to forget Iran-Contra back in 1987. It's a pledge we're still keeping in 2019.

At the end of the tumultuous 1960s and '70s, the great Joan Didion wrote: "We tell ourselves stories in order to live ... We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices." In American politics, the most workable choice is Watergate, and it's been that way ever since Richard Nixon waved from the helicopter steps in 1974.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then--a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement--probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump.

Forty-five years later, as the world of punditry struggles to put the sprawling amorality of Donald Trump into a tidy box, TV producers raised in the dark shadows of Deep Throat continually invite the stars of Watergate -- John Dean, Woodward and Bernstein, Jill Wine-Banks -- into your living room to impose reason and order. And why not? The system worked, right? There were checks and balances, just like the Founding Fathers drew it up. The journalists, the judges, and Congress did their jobs and masses overwhelmingly approved.

I've not seen one cable-TV guest from Reagan's Iran-Contra scandal during the current crisis, even though what happened then -- a half-generation after Watergate, as America's great political divide was starting to harden like wet sidewalk cement -- probably better explains the looming national crack-up over Trump. It was a post-Watergate restoration of situational ethics over the rule of law, and a new understanding that impeachment was a political act in a time when raw partisanship was just beginning to trump (pun intended) principle.

The crimes of Iran-Contra were shocking when they were revealed in real-time, but the murky ending has allowed the story to drift into relative obscurity, especially as the American right-wing embarked on a campaign (which I wrote a book about) to create a mythical Ronald Reagan who'd be worthy of a spot on Mt. Rushmore. If you're one of the majority of folks born since 1970 (or spent 1987 grooving on Van Halen records instead of politics) here's a super-quick refresher.

Reagan, who seemed like the most conservative and reactionary president America could possibly have (yes, we were that naive), centered his foreign policy on fighting Communism and socialism around the globe. That included Central America, where a leftist, U.S.-opposed regime had taken control in Nicaragua. But Reagan's biggest headache proved to be terrorism in the Middle East, including a string of kidnappings of Americans in Lebanon.

You'd think one problem had little to do with the other. But the 40th president agonized over the hostages and was willing to take extreme, secret measures to free them. His team learned that Iran -- the former U.S.-ally-turned-enemy after 1979's Islamic revolution, now in a war with Iraq and desperately needing military aid -- had sway with the hijackers. That gave rise to a hidden network, using unsavory middlemen, of trading arms for hostages.

But the scheme generated extra profits, right at a time when Reagan's other big foreign-policy frustration was Congress balking at funds for his would-be allies in Central America, including a human-rights nightmare of a right-wing reactionary movement in Nicaragua called the Contras. In fact, during Reagan's first term, Congress barred aiding the Contras in a measure known as the Boland Amendment -- which Team Reagan decided to circumvent by steering the off-the-book profits from the Iranian arms deals to the Contras. It was a brazen, outrageous scheme that unraveled quickly when -- on October 5, 1986 -- an American pilot named Eugene Hasenfus flying some of that illicit aid to the Contras was shot down, captured, and confessed everything.

This massive breach of the public trust happened just a dozen years after the national trauma of Watergate. Objectively, it's hard not to see a throughline of high crimes and misdemeanors from Nixon's dirty tricks and cover-ups to both Iran-Contra and Trump's regime of wrongdoing that spiked with the Ukraine misadventure. Each involved a power-hungry president using illegal methods to trample their opposition -- whether on Capitol Hill or rivals for the presidency -- and then lying about it on massive scale. A former CIA officer named Felix Rodriguez tried to warn a key Iran-Contra figure that this "could be worse than Watergate and ... could destroy the president."

It didn't, though. Yes, there were nationally televised hearings in Congress, and an aggressive prosecutor who criminally charged a number of key Reagan aides and other players. But there was never any serious appetite for impeaching the Gipper. There was a perfect storm of reasons why. Reagan was always personally popular--despite moments when his political approval plunged -- and the fact that he was America's oldest president, coming off as disengaged, actually bolstered a sense that he was out-of-the-loop on the worst crimes. But Reagan had also been elected on an explicit promise to move America past the malaise of the 1970s, which had included Watergate. By 1987, many voters preferred ignorant triumphalism over the scold of accountability.

Even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism.

And even though it was a relatively short time after Watergate, Iran-Contra was an early warning of what was already becoming the key feature of modern politics: Tribalism, as previously conservative Southern Democrats and northern liberal Republicans had by now mostly switched parties. Reagan was protected in Iran-Contra by a solid GOP wall led by a Wyoming Republican named Dick Cheney, who insisted "[t]here was no constitutional crisis, no systematic disrespect for 'the rule of law,' no grand conspiracy, and no Administration-wide dishonesty or cover up."

Cheney also was, and still is, a champion of the "unitary executive theory" which sees an American president holding almost-monarchical powers that must thwart efforts by Congress or the courts to interfere. Indeed, one reason why Iran-Contra ended with Reagan not only still in office but as the future icon of American conservatism was Republicans' willingness to openly embrace the exercise of power (unlike Nixon telling his aides to "stonewall" and cover-up) and wrap it in a cloth of patriotism. This was punctuated by the bravado of Lt. Col. Oliver North who gave swashbuckling testimony in full uniform, beat a criminal rap and became a hero of the right.

Some 32 years later, the square peg of Trump's impeachment won't fit into the round hole of Watergate, and maybe that's because the GOP is running the Iran-Contra playbook of massive resistance while hailing the idea of an all-powerful, literally unimpeachable chief executive (something no one desired in 1787). (I won't go off on a complicated tangent but there's also an argument that Bill Clinton's 1998 impeachment was a B-side to Iran-Contra, because in a very different way it cemented the same central premise -- that impeachment is partisan, ugly and not what the Founding Fathers would have wanted...even though it was what they wanted.)

None of this is a guarantee that Trump ends like Iran-Contra did. After all, Reagan was arguably one of the most-liked U.S. presidents while Trump is loathed even by some of those who vote for him. More importantly, the naked political greed of Trump's Ukraine scheme is arguably morally much worse than the more ideological crimes of the 1980s.

But let's be honest: The principles first laid bare in Iran-Contra -- a deference to the raw exercise of power, including a willingness to overlook the rule of law--have become America's cruel guiding spirit in the 21st century. On TV, Watergate -- with its quaint mantra of checks and balances and its moral that "the system worked" -- remains the story we tell ourselves to live, even as a Republican Senate prepares to snowplow that plot line in January.

And there's a depressing but fitting footnote to all of this. All of the major administration officials convicted of crimes in Iran-Contra -- former defense secretary Caspar Weinberger, and five others--were pardoned by outgoing President George H.W. Bush (he'd been Reagan's VP) on Christmas Eve, 1992. The move -- which ensured no one would be held accountable for one of the worst scandals in U.S. history--had gotten an OK from Bush 41's attorney general, a man whose belief in a unitary chief executive with quasi-dictatorial powers has only grown in the years since then. The attorney general then is the attorney general now: William Barr.