Only a few years ago, analysts were warning that Mexico was at risk of becoming a "failed state." These days, the Mexican government appears to be doing a much better PR job.

Despite the devastating and ongoing drug war, the story now goes that Mexico is poised to become a "middle-class" society. As establishment apostle Thomas Friedman put it in the

New York Times, Mexico is now one of "the more dominant economic powers in the 21

st century."

But this spin is based on superficial assumptions. The small signs of economic recovery in Mexico are grounded largely on the return of maquiladora factories from China, where wages have been increasing as Mexican wages have stagnated. Under-cutting China on labor costs is hardly something to celebrate. This trend is nothing but the return of the same "free-trade" model that has failed the Mexican people for 20 years.

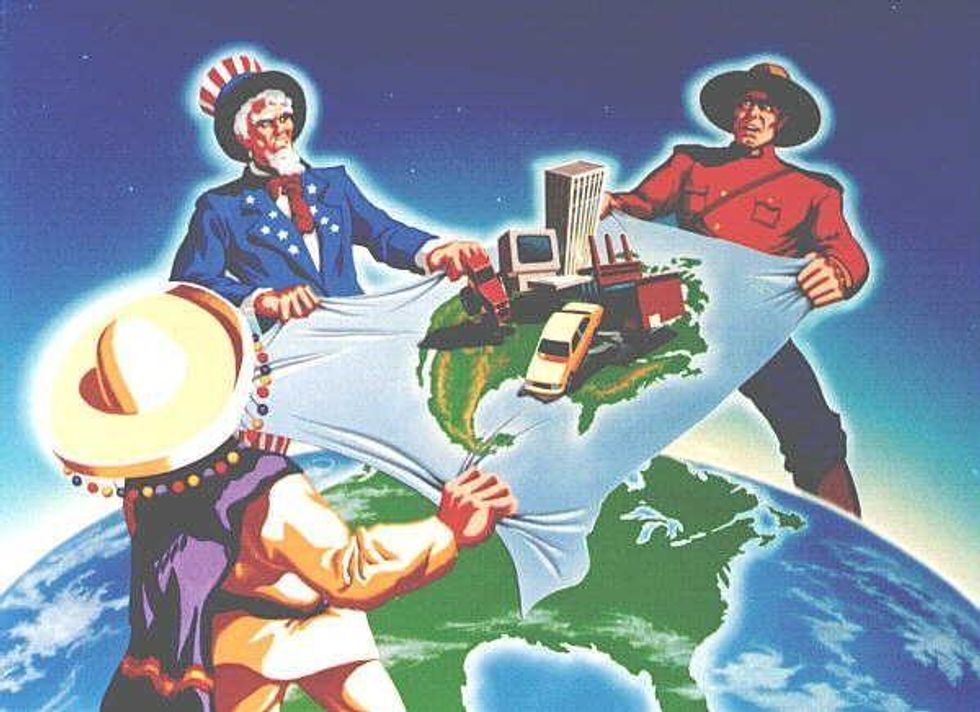

The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which was ratified in 1993 and went into effect in 1994, was touted as the cure for Mexico's economic "backwardness." Promoters argued that the trilateral trade agreement would dig Mexico out of its economic rut and modernize it along the lines of its mighty neighbor, the United States.

The story went like this:

NAFTA was going to bring new U.S. technology and capital to complement Mexico's surplus labor. This in turn would lead Mexico to industrialize and increase productivity, thereby making the country more competitive abroad. The spike in productivity and competiveness would automatically cause wages in Mexico to increase. The higher wages would expand economic opportunities in Mexico, slowing migration to the United States.

In the words of the former President Bill Clinton, NAFTA was going to "promote more growth, more equality and better preservation of the environment and a greater possibility of world peace." Mexico's president at the time, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, echoed Clinton's sentiments during a commencement address at MIT: "NAFTA is a job-creating agreement," he said. "It is an environment improvement agreement." More importantly, Salinas boasted, "it is a wage-increasing agreement."

As the 20th anniversary of NAFTA approaches, however, the verdict is indisputable: NAFTA failed to spur meaningful and inclusive economic growth in Mexico, pull Mexicans out of unemployment and underemployment, or reduce poverty. By all accounts, it has done just the opposite.

The Verdict Is In

Official statistics show that from 2006 to 2010, more than 12 million people joined the ranks of the impoverished in Mexico, causing the poverty level to jump to 51.3 percent of the population. According to the United Nations, in the past decade Mexico saw the slowest reduction in poverty in all of Latin America.

Rampant poverty in Mexico is a product of IMF and World Bank-led neoliberal policies--such as anti-inflationary policies that have kept wages stagnant--of which "free-trade" pacts like NAFTA are part and parcel. Another factor is the systematic failure to create good jobs in the formal sectors of the economy. During Felipe Calderon's presidency, the share of the Mexican labor force relying on informal work--such as selling chewing gum and other low-cost products on the street--grew to nearly 50 percent.

Even the wages in the manufacturing sector, which NAFTA cheerleaders argued would benefit the most from trade liberalization, have remained extremely low. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Mexican manufacturing workers made an average hourly wage of only $4.53 in 2011, compared to $26.87 for their U.S. counterparts. Between 1997 and 2011, the U.S.-Mexico manufacturing wage gap narrowed only slightly, with Mexican wages rising from 13 to 17 percent of the level earned by American workers. In Brazil, by contrast, manufacturing wages are almost double Mexico's, and in Argentina almost triple.

Mexico's stagnant wages are celebrated by free traders as an opportunity for U.S. businesses interested in outsourcing. According to one report by the McKinsey management consulting firm, "for a company motivated primarily by cost, Mexico holds the most attractive position among the Latin American countries we studied. ... Mexico's advantages start with low labor costs."

But even as the damning evidence against NAFTA continues to roll in, entrenched advocates of the trade agreement have been busy crafting new arguments. In his recent book, Mexico: A Middle Class Society, NAFTA negotiator Luis De la Calle and his co-author argue that the trade agreement has given rise to a growing Mexican middle class by providing consumers with higher quality, U.S- made goods. The authors proclaim that "NAFTA has dramatically reduced the costs of goods for Mexican families at the same time that the quality and variety of goods and services in the country grew."

Most of the economic indicators included in the book conveniently fail to account for the 2008-2009 financial crisis, which hit Mexico worse than almost any other Latin American country. The result has been skyrocketing inequality. As the Guardian reported last December, "ever more Mexican families have acquired the trappings of middle-class life such as cars, fridges, and washing machines, but about half of the population still lives in poverty."

The indicators of consumption that suggest the rise of Mexico's middle class also exclude the dramatic increase in food prices in recent years, which has condemned millions of Mexicans to hunger. Twenty-eight million Mexicans are facing "food poverty," meaning they lack access to sufficient nutritious food. According to official statistics, more than 50,000 people died of malnutrition between 2006 and 2011. That's almost as many as have died in Mexico's drug war, which dramatically escalated under Calderon and has continued under President Enrique Pena Nieto.

The food crisis has coincided with the "Walmartization" of the country. In 1994 there were only 14 Walmart retail stores in all of Mexico. Now there are more than 1,724 retail and wholesale stores. This is almost half the number of U.S. Walmarts, and far more than any other country outside the United States. The proliferation of Walmart and other U.S. big-box stores in Mexico since NAFTA came into effect has ushered in a new era of consumerism--in part through an aggressive expansion built on political bribes and the destruction of ancient Aztec ruins.

The arguments developed prior to the signing of NAFTA focused primarily on the claim that the trade agreement would make Mexico a nation of producers and exporters. These initial promises failed to deliver. Throughout the NAFTA years, the bulk of Mexico's manufacturing "exports" have come from transnational car and technology companies. Not surprisingly, Mexico's intra-industry trade with the United Sates is the highest of any Latin American country. Yet the percentage of Mexican companies that are actually exporters is vanishingly small, and imports of food into Mexico have surged.

Same Snake Oil, Different Pitch

Because their initial promises utterly failed to deliver, the NAFTA pushers are now hyping "consumer benefits" to justify new trade agreements, including the Trans-Pacific Partnership. One of the most extreme examples of this spin is an article in The Washington Post that celebrates a "growing middle class" in Mexico that is "buying more U.S. goods than ever, while turning Mexico into a more democratic, dynamic and prosperous American ally." Devoid of all logic, it goes on to say that "Mexico's growth as a manufacturing hub is boosted by low wages." How can low wages make people more prosperous?

The Post also boasts that in "Mexico's Costco stores, staples such as tortilla chips and chipotle salsa are trucked in from factories in California and Texas that produce for both sides of the border." Is this something to celebrate? The influx of traditional Mexican food staples, starting with maize, and goods from the United States has displaced and dislocated millions of Mexican small-scale farmers, producers, and small businesses. And not only that, Mexicans' increasing consumption of processed foods and beverages from the United States has made the country the second-most obese in the world.

In essence, NAFTA advocates have been reduced to saying: "so maybe NAFTA didn't help Mexico reduce poverty or increase wages. But hey! At least it gave it Walmart, Costcos, and sweat shops."

The bankruptcy of NAFTA's promises is only compounded by the poverty of this consolation.