King CONG vs. Solartopia

As you ride the Amtrak along the Pacific coast between Los Angeles and San Diego, you pass the San Onofre nuclear power plant, home to three mammoth atomic reactors shut by citizen activism.

Framed by gorgeous sandy beaches and some of the best surf in California, the dead nukes stand in silent tribute to the popular demand for renewable energy. They attest to one of history's most powerful and persistent nonviolent movements.

As you ride the Amtrak along the Pacific coast between Los Angeles and San Diego, you pass the San Onofre nuclear power plant, home to three mammoth atomic reactors shut by citizen activism.

Framed by gorgeous sandy beaches and some of the best surf in California, the dead nukes stand in silent tribute to the popular demand for renewable energy. They attest to one of history's most powerful and persistent nonviolent movements.

But 250 miles up the coast, two reactors still operate at Diablo Canyon, surrounded by a dozen earthquake faults. They're less than seventy miles from the San Andreas, about half the distance of Fukushima from the quake line that destroyed it. Should any quakes strike while Diablo operates, the reactors could be reduced to rubble and the radioactive fallout would pour into Los Angeles.

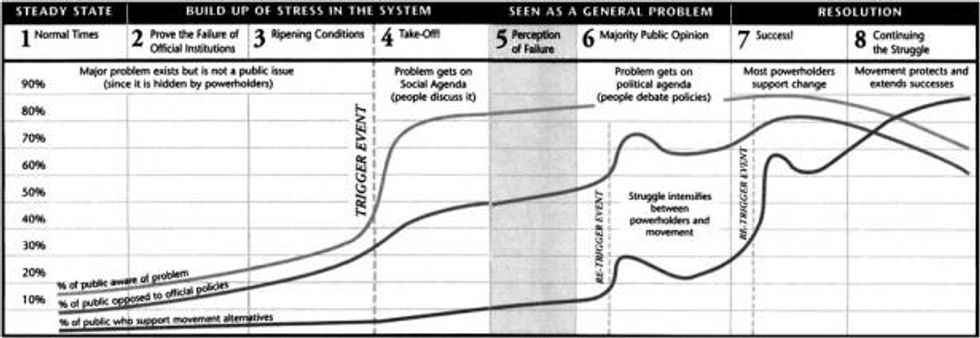

Some 10,000 arrests of citizens engaged in civil disobedience have put the Diablo reactors at ground zero in the worldwide No Nukes campaign. But the epic battle goes far beyond atomic power. It is a monumental showdown over who will own our global energy supply, and how this will impact the future of our planet.

On one side is King CONG (Coal, Oil, Nukes, and Gas), the corporate megalith that's unbalancing our weather and dominating our governments in the name of centralized, for-profit control of our economic future. On the other is a nonviolent grassroots campaign determined to reshape our power supply to operate in harmony with nature, to serve the communities and individuals who consume and increasingly produce that energy, and to build the foundation of a sustainable eco-democracy.

The modern war over America's energy began in the 1880s, when Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla clashed over the nature of America's new electric utility business. It is now entering a definitive final phase as fossil fuels and nuclear power sink into an epic abyss, while green power launches into a revolutionary, apparently unstoppable, takeoff.

In many ways, the two realities were separated at birth.

Edison pioneered the idea of a central grid, fed by large corporate-owned power generators. Backed by the banker J. Pierpont Morgan, Edison pioneered the electric light bulb and envisioned a money-making grid in which wires would carry centrally generated electricity to homes, offices, and factories. He started with a coal-burning generator at Morgan's Fifth Avenue mansion, which in 1882 became the world's first home with electric lights.

Morgan's father was unimpressed. And his wife wanted that filthy generator off the property. So Edison and Morgan began stringing wires around New York City, initially fed by a single power station. The city was soon criss-crossed with wires strung by competing companies.

But the direct current produced by Edison's generator couldn't travel very far. So he offered his Serbian assistant, Nikola Tesla, a $50,000 bonus to solve the problem.

Tesla did the job with alternating current, which Edison claimed was dangerous and impractical. He reneged on Tesla's bonus, and the two became lifelong rivals.

To demonstrate alternating current's dangers, Edison launched the "War of the Currents," using it to kill large animals (including an elephant). He also staged a gruesome human execution with the electric chair he secretly financed.

Edison's prime vision was of corporate-owned central power stations feeding a for-profit grid run for the benefit of capitalists like Morgan.

Tesla became a millionaire working with industrialist George Westinghouse, who used alternating current to establish the first big generating station at Niagara Falls. But Morgan bullied him out of the business. A visionary rather than a capitalist, Tesla surrendered his royalties to help Westinghouse, then spent the rest of his haunted, complex career pioneering various inventions meant to produce endless quantities of electricity and distribute it free and without wires.

Meanwhile, the investor-owned utilities bearing Edison's name and Morgan's money built the new grid on the back of big coal-burners that poured huge profits into their coffers and lethal pollutants into the air and water.

In the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal established the federally owned Tennessee Valley Authority and Bonneville Power Project. The New Deal also strung wires to thousands of American farms through the Rural Electrification Administration. Hundreds of rural electrical cooperatives sprang up throughout the land. As nonprofits with community roots and ownership, the co-ops have generally provided far better and more responsive service than the for-profit investor-owned utilities.

But it was another federal agency--the Atomic Energy Commission--that drove the utility industry to the crisis point we know today. Coming out of World War II, the commission's mandate was to maintain our nascent nuclear weapons capability. After the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, it shifted focus, prodded by Manhattan Project scientists who hoped the "Peaceful Atom" might redeem their guilt for inventing the devices that killed so many.

When AEC chairman Lewis Strauss promised atomic electricity "too cheap to meter," he heralded a massive government commitment involving billions in invested capital and thousands of jobs. Then, in 1952, President Harry Truman commissioned a panel on America's energy future headed by CBS Chairman William Paley. The commission report embraced atomic power, but bore the seeds of a worldview in which renewable energy would ultimately dominate. Paley predicted the United States would have thirteen million solar-heated homes by 1975.

Of course, this did not happen. Instead, the nuclear power industry grew helter-skelter without rational planning. Reactor designs were not standardized. Each new plant became an engineering adventure, as capability soared from roughly 100 megawatts at Shippingport in 1957 to well over 1,000 in the 1970s. By then, the industry was showing signs of decline. No new plant commissioned since 1974 has been completed.

But with this dangerous and dirty power have come Earth-friendly alternatives, ignited in part by the grassroots movements of the 1960s. E.F. Schumacher's Small Is Beautiful became the bible of a back-to-the-land movement that took a new generation of veteran activists into the countryside.

Dozens of nonviolent confrontations erupted, with thousands of arrests. In June 1978, nine months before the partial meltdown at Three Mile Island, the grassroots Clamshell Alliance drew 20,000 participants to a rally at New Hampshire's Seabrook site. And Amory Lovins's pathbreaking article, "Energy Strategy: The Road Not Taken," posited a whole new energy future, grounded in photovoltaic and wind technologies, along with breakthroughs in conservation and efficiency, and a paradigm of decentralized, community-owned power.

As rising concerns about global warming forced a hard look at fossil fuels, the fading nuclear power industry suddenly had a new selling point. Climate expert James Hansen, former Environmental Protection Agency chief Christine Todd Whitman, and Whole Earth Catalog founder Stewart Brand began advocating atomic energy as an answer to CO2 emissions. The corporate media began breathlessly reporting a "nuclear renaissance" allegedly led by hordes of environmentalists.

But the launch of Peaceful Atom 2.0 has fallen flat.

As I recently detailed in an online article for The Progressive, atomic energy adds to rather than reduces global warming. All reactors emit Carbon-14. The fuel they burn demands substantial CO2 emissions in the mining, milling, and enrichment processes. Nuclear engineer Arnie Gundersen has compiled a wide range of studies concluding new reactor construction would significantly worsen the climate crisis.

Moreover, attempts to recycle spent reactor fuel or weapons material have failed, as have attempts to establish a workable nuclear-waste management protocol. For decades, reactor proponents have argued that the barriers to radioactive waste storage are political rather than technical. But after six decades, no country has unveiled a proven long-term storage strategy for high-level waste.

For all the millions spent on it, the nuclear renaissance has failed to yield a single new reactor order. New projects in France, Finland, South Carolina, and Georgia are costing billions extra, with opening dates years behind schedule. Five projects pushed by the Washington Public Power System caused the biggest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history. No major long-standing green groups have joined the tiny crew of self-proclaimed "pro-nuke environmentalists." Wall Street is backing away.

Even the split atom's most ardent advocates are hard-pressed to argue any new reactors will be built in the United States, or more than a scattered few anywhere else but China, where the debate still rages and the outcome is uncertain.

Today there are about 100 U.S. reactors still licensed to operate, and about 450 worldwide. About a dozen U.S. plants have shut down in the last several years. A half dozen more are poised to shut for financial reasons. The plummeting price of fracked gas and renewable energy has driven them to the brink. As Gundersen notes, operating and maintenance costs have soared as efficiency and performance have declined. An aging, depleted skilled labor force will make continued operations dicey at best.

And nuclear plants have short lifespans for safe operation.

"When the reactor ruptured on March 11, 2011, spewing radioactivity around the northern hemisphere, Fukushima Daiichi had been operating only one month past its fortieth birthday," Gundersen says.

But the nuclear power industry is not giving up. It wants some $100 billion in state-based bailouts. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently pushed through a $7.6 billion handout to sustain four decrepit upstate reactors. A similar bailout was approved in Ohio. Where once it demanded deregulation and a competitive market, the nuclear industry now wants re-regulation and guaranteed profits no matter how badly it performs.

The grassroots pushback has been fierce. Proposed bailouts have been defeated in Illinois and are under attack in New York and Ohio. A groundbreaking agreement involving green and union groups has set deadlines for shutting the Diablo reactors, with local activists demanding a quicker timetable. Increasingly worried about meltdowns and explosions, grassroots campaigns to close old reactors are ramping up throughout the United States and Europe. Citizen action in Japan has prevented the reopening of nearly all nuclear plants since Fukushima.

Envisioning the "nuclear interruption" behind us, visionaries like Lovins see a decentralized "Solartopian" system with supply owned and operated at the grassroots.

The primary battleground is now Germany, with the world's fourth-largest economy. Many years ago, the powerful green movement won a commitment to shut the country's fossil/nuclear generators and convert entirely to renewables. But the center-right regime of Angela Merkel was dragging its feet.

In early 2011, the greens called for a nationwide demonstration to demand the Energiewende, the total conversion to decentralized green power. But before the rally took place, the four reactors at Fukushima blew up. Facing a massive political upheaval, and apparently personally shaken, Chancellor Merkel (a trained quantum chemist) declared her commitment to go green. Eight of Germany's nineteen reactors were soon shut, with plans to close the rest by 2022.

That Europe's biggest economy was now on a soft path originally mapped out by the counterculture prompted a hard response of well-financed corporate resistance. "You can build a wind farm in three to four years," groused Henrich Quick of 50 Hertz, a German transmission grid operator. "Getting permission for an overhead line takes ten years."

Indeed, the transition is succeeding faster and more profitably than its staunchest supporters imagined. Wind and solar have blasted ahead. Green energy prices have dropped and Germans are enthusiastically lining up to put power plants on their rooftops. Sales of solar panels have skyrocketed, with an ever-growing percentage of supply coming from stand-alone buildings and community projects. The grid has been flooded with cheap, green juice, crowding out the existing nukes and fossil burners, cutting the legs out from under the old system.

In many ways it's the investor-owner utilities' worst nightmare, dating all the way back to the 1880s, when Edison fought Tesla. Back then, the industry-funded Edison Electric Institute warned that "distributed generation" could spell doom for the grid-based industry. That industry-feared deluge of cheap, locally owned power is now at hand.

In the United States, state legislatures dominated by the fossil fuel-invested billionaire Koch brothers have been slashing away at energy efficiency and conservation programs. Ohio, Arizona, and other states that had enacted progressive green-based transitions are now shredding them. In Florida, a statewide referendum pretending to support solar power was in fact designed to kill it.

In Nevada, homeowners who put solar panels on their rooftops are under attack. The state's monopoly utility, with support from the governor and legislature, is seeking to make homeowners who put solar panels on their rooftops pay more than others for their electricity.

But it may be too little, too late. In its agreement with the state, unions, and environmental groups, Pacific Gas and Electric has admitted that renewables could, in fact, produce all the power now coming from the two decaying Diablo nukes. The Sacramento Municipal Utility District shut down its one reactor in 1989 and is now flourishing with a wave of renewables.

The revolution has spread to the transportation sector, where electric cars are now plugging into outlets powered by solar panels on homes, offices, commercial buildings, and factories. Like nuclear power, the gas-driven automobile may be on its way to extinction.

Nationwide, more than 200,000 Americans now work in the solar industry, including more than 75,000 in California alone. By contrast, only about 100,000 people work in the U.S. nuclear industry. Some 88,000 Americans now work in the wind industry, compared to about 83,000 in coal mines, with that number also dropping steadily.

Once the shining hope of the corporate power industry, atomic energy's demise represents more than just the failure of a technology. It's the prime indicator of an epic shift away from corporate control of a grid-based energy supply, toward a green power web owned and operated by the public.

As homeowners, building managers, factories, and communities develop an ever-firmer grip on a grassroots homegrown power supply, the arc of our 128-year energy war leans toward Solartopia.